A randomly comprehensive survey of extraordinary movie experiences from the art house to the grindhouse, featuring the good, the bad, the ugly, but not the boring or the banal.

Sunday, November 29, 2015

On the Big Screen: SPOTLIGHT (2015)

Friday, November 27, 2015

THE DAUGHTER OF DAWN (1920)

Norbert Myles and Richard Banks's scenario is self-consciously archetypal in a generic way. He's less interested in a narrative grounded in the authentic details and rhythm of Native life than in "the eternal triangle" that could appear anywhere, at any time. This time it's a triangle of a woman and two men. The woman is our title character (Esther Labarre), named for the time of her birth but in fact the daughter of a Kiowa chief. She has two suitors. One, Black Wolf (Jack Sankadota), is rich in goods. The other, White Eagle (White Parker) is a hunk compared to the pot-bellied Black Wolf. White Eagle is also a good citizen; he locates a buffalo herd and leads the Kiowas on a successful hunt that highlights the picture. The chief knows that Black Wolf can offer more for his daughter but he also respects her opinion and her emotions. Knowing her preference for White Eagle, the chief decides to let a trial of courage decide her future.

Black Wolf and White Eagle are to jump off a cliff. It's more steep than high but it promises a rough landing. Whoever survives will win the Daughter of Dawn. I'd hate to think any actual tribe settled such disputes that way, but no one claimed that this is an anthropological text. Anyway, both men survive, but Black Wolf survives by cowering on a ledge while White Eagle nobly takes his lumps all the way down. He'll be fine, while Black Wolf is shamed out of the tribe. On the rebound, he finally accepts the loyalty of Red Wing (Wanada Parker), who's been pining inexplicably for this lout through the whole picture and now volunteers to share his exile.

Rather than take his punishment like a man, Black Wolf turns traitor, betraying the Kiowas to this film's bad guys, the Comanches. He shows them the way to the Kiowa village, promising them horses and women, so long as he gets Daughter of Dawn. To cut to the chase, a recovered White Eagle leads the rescue mission, setting up a final showdown with Black Wolf. This climactic fight is reasonably well staged for 1920, Myles gradually moving closer, cut by cut, from long shot to close-up. But he follows it with a corny, clunky anticlimax as Red Wing knifes herself out of implausible grief for this dead Bluto of the Kiowas and an intertitle comments: "Constancy, thy name is Red Wing."

As a Native critic might have said, "Ugh." But while the story is the stuff of pulp fiction, with apologies to pulp fiction, Daughter of Dawn is fascinating even more as a piece of cinematic history than as a relic of Native folkways. For silent film buffs there's inherent drama to every rediscovery, and Daughter deserves its place on the National Film Registry (Class of 2013) regardless of its dramatic limitations. With so many major-studio Hollywood pictures from the silent era still missing or unlikely to be found, it's a wonder that an outlier project like this one can be seen so easily today, and that shouldn't be taken for granted.

Tuesday, November 24, 2015

WHEN AN ALIEN ROBOT CRASH LANDS IN TROY, NY (2015)

In slightly less than an hour, Kendall follows his little robot from his crash site through the Collar City known as the Home of Uncle Sam, the place of my birth and my daily work. In the first section, "Terror," the robot struggles to find an exit from a post-industrial wasteland. In the second, "Wonder," he makes it into the city proper, exploring downtown Troy during one Saturday's outdoor farmer's market. In "Exploration" he tries to make contact with the planet's indigenous life, primarily an indifferent cat, and takes a treacherous trip through some parkland. In the final section, "Love/Freedom," he discovers the possibility of companionship and appears to find fulfillment as a child's toy.

The robot is Kendall's only special effect, but his dogged mobility brings this micro-budgeted film to life. Much of the film consists of long tracking shots following the robot as he scoots down roads of varying smoothness. These are impressive compositions, and they only get more so when the robot reaches populated areas. The Farmers' Market sequence is a modest tour de force as Kendall follows the robot through a crowded Monument Square and environs, leaving you wondering how the little guy doesn't get stepped on, or how no one ever sued Kendall for tripping over the thing. It takes you back a little to the early days of silent comedy when Mack Sennett's troupe would set up shop at public events and make comedy wherever they might find it. There aren't really any gags in Alien Robot, but it's still a sincere throwback to that century-old spirit. That comes through in the final sequence, when the robot, after watching two people enjoy a railyard picnic, befriends a little girl playing alone in her yard. There's something sentimental if not corny to this courtship, as the girl guides the robot with her little stick and finally does a happy dance as he circles elegantly around her. The closing high-five is a more modern touch, of course.

If the robot is in some ways a 21st century silent clown, in another way he's a humble embodiment of cinema itself. Seeing Troy from ankle-level and on the move from the robot's perspective must be like seeing things through a movie camera for the first time; the artifice automatically changing what we see as well as how we see it. Kendall has a few more tricks up his sleeve than tracking shots; like a good silent director he's also adept at montage, which he uses to establish the first terrifying, then wondrous strangeness of the cityscape. But when he's following the robot through the city he arrives at something like pure cinema. And on top of that, like many a silent film Alien Robot has an original score, which I was lucky to hear performed live by the band Lastdayshining, including Kendall. The score elevates the film, underscoring its often ecstatic sense of discovery and wonder. The combined effect is more artistry than amateurism -- which is more than I can say for that poster -- reminding us of what can still be done with limited resources and an understanding that cinema itself is a special effect. I don't want to exaggerate the film's virtues, but it definitely deserves a lot of appreciation, just as Bobby Kendall deserves encouragement in his future ventures.

Sunday, November 22, 2015

On the Big Screen: THE GOLDEN BED (1925)

The Golden Bed is about the fall of an American family and how they nearly take a rising family with them. In Atlanta live the increasingly shabby yet ever genteel Peakes and the aspiring hardscrabble Holtzes. Papa Peake (Henry B. Walthall of Birth of a Nation fame) was bred to spend money but not to earn it, a title tells us. He's staked his family's future on his beautiful, spoiled, blonde daughter Flora Lee (Lillian Rich), while neglecting still-pretty but definitely second-best Margaret (Vera Reynolds). Flora has been bred to land a rich husband; early proof of her talent is the way young Admah Holtz, a candymaker's son (who grows up into Rod La Rocque) will give Flora free peppermints while making Margaret pay. As Papa patiently explains to a jealous Margaret, when Flora lands the right husband there'll be candy for everybody. Everything works out just in time; Flora lands a European aristocrat and Papa hosts the wedding the same day that the bank repossesses his furniture. As it is, Margaret still has to go out into the world and get a job. She goes to work for Admah, who has inherited the store and the name of "Candy" Holtz. Margaret hits the ground running with ideas for Admah to spruce up his slovenly shop, e.g., take the used flypaper off the candy shelves. Admah appreciates her entrepreneurial sense but is almost cruelly oblivious to the way Margaret plainly pines for him. He jokingly orders her to leave by the employees' back entrance after hiring her, not realizing how humiliating the moment is for her, though she pluckily jokes about noblesse oblige. Worse, he'd gone to Flora's wedding and hovered at the margins like a neglected puppy, except that Flora didn't neglect him. She saved him a flower from her bouquet and threw it to him while her new hubby wasn't looking. He still has a chance.

Now that Margaret has civilized the place and Admah isn't pulling taffy in the shop window anymore, the Candy Holtz business picks up. With Margaret as his conscience Admah rejects schemes to adulterate his produce by using sugar substitutes. As they condemn Atlanta to Type 2 diabetes, Flora is abruptly widowed during an Alpine vacation when her hubby and a rival with whom she'd started an affair fight their way off a cliff. I guess you can call that a De Mille touch, down to a primitive version of the Saboteur effect as the two men take the plunge. Now that Flora's free again, not to mention left out of hubby's will "for some reason," Margaret doesn't have a chance with Admah. Flora becomes Flora Holtz virtually by fait accompli and Margaret practically vanishes from the picture for an hour. Candy Holtz has achieved his dream, but he's also cut his own throat. Like father, like daughter; Flora lives to spend and is determined to rule Atlanta society, even if Admah can't really afford it. When she loses her bid to be hostess of the Peachtree Ball, she browbeats Admah into hosting a rival ball, playing on his class insecurity by blaming his working-class background for her defeat. Admah has been warned by his banker, whose wife won the right to host the ball, that he'll get no more credit if he continues his extravagance, but he blows practically all of his latest $40,000 loan on staging an insane candy-themed ball. This is the true De Millean showstopper, a nutty (and chocolatey!) masterpiece of demented set design (topic for future discussion; De Mille's true heir in our time is Tim Burton) garnished with hostesses in costumes made of candy -- that is to say, edible costumes. C.B. doesn't mean that in a purely theoretical sense, either. Censors reportedly went nuts over scenes of men nibbling near sensitive areas on those outfits. So which ball would you go to? Most of Atlanta society agreed with you, but Admah and Flora's moment of triumph is about to turn to ashes like many Cinderella stories. You see, after all that party planning Admah is running on fumes and Flora's dressmaker won't let her have her party gown until she pays her back bills. In a Dreiserian moment of decision (read Sister Carrie, or read about it if you're in a hurry), Admah takes the day's sales receipts out of a safe to pay the dressmaker, and that, children, is what we call embezzlement. Oh, and Flora is practically cheating under his nose with social butterfly Bunny (a young Warner Baxter). With Flora walking out on him and the police closing in, Admah may think the world has turned against him but this is really a moment of self-destruction, perfectly illustrated by De Mille in what should be this film's signature shot. In a self-parody of Samson and Delilah a quarter-century in advance, an enraged, self-pitying Admah brings a full-sized candy gazebo crashing down behind him by pushing the pillars apart. Next on his schedule: five years in prison.

It would be too brutal if the film ended here, so we get a final act in which Flora is punished and Admah is reformed through labor, while Margaret reopens the original Candy Holtz store and proves herself a successful businesswoman in her own right. This sets up a sad, almost chilling emotional climax that anticipates not only Orson Welles's Maginificent Ambersons but the mad pathos of southern gothic literature. In short, Bunny kicks Flora to the curb at the first opportunity, and with her youth gone and her looks going its only downhill for her. On the day Admah is released from prison a threadbare, moribund Flora makes her way to the old Peake mansion, which is now a boarding house. She has a poignant reunion with her old pet monkey, now working for an organ grinder -- I could write a whole post on the monkey as her totem animal going back to a childhood doll, the way its mischief at the Candy Holtz store embodies Flora's destructive rivalry with Margaret, and whether the monkey's name, Louella, is a dig at Parsons the gossip columnist -- before the new mistress of the house reluctantly lets her tour the place. How far Flora has fallen is hard to say; she may be homeless, but there's no hint of prostitution, and I might have found her comeuppance excessive except that I know that Hollywood actresses actually did fall that far if not further. Anyway, Flora's old Golden Bed is still in its old place -- I should explain that Admah had bought the house for her, and presumably refurnished it, as a wedding present -- but its crowning swan's head is broken and tied to the bed, upside-down, with wire. Meanwhile, as I mentioned, Admah is getting out of prison, and Margaret has put together a nice dinner to welcome him back. But he -- can't -- let -- go! Some morbid instinct draws him, too, to the boarding house, where he finds you-know-who in the Golden Bed. She recognizes him, but seems to have forgotten, in her decrepitude, that she and the "Candy Man" had been married. You'd like to think that her calling out for Bunny in her last moments would be the ultimate deal-breaker, but I think she actually has to die before Admah will finally quit her. Of course, Margaret has no clue about this nearby deathwatch and sadly falls asleep at an untouched dinner table. But the film does us the kindness of closing on a things-could-yet-be-worse note. After all, neither Admah nor Margaret commits suicide. Instead, he finally shows up about twelve hours late, and "your sister died in my arms" proves a satisfactory excuse. The Golden Bed actually closes on a note of bittersweet perseverance as the two survivors watch a construction crew reporting for work across the street and realize that the only thing to do is start over.

I feel justified in giving a detailed synopsis because most of you are never going to see this film. I hope the synopsis conveys that you're missing out on something because Golden Bed packs a wallop that's probably unexpected in a Cecil B. De Mille movie. It's as anti-romantic a movie as C.B. ever made while retaining considerable emotional power. In fact, it's an all-out attack on a certain romanticism, in movies and the wider culture, that Walthall, D. W. Griffith's Little Colonel, may have purposefully symbolized. Golden Bed is a vindication of bourgeois virtues, as forgotten by Admah but learned under pressure by Margaret, against an aristocratic romanticism of leisure and conspicuous consumption that Flora Peake was shaped to embody and Admah Holtz could not help idolizing. Knowing that Flora was consciously shaped by her father into the creature she becomes justifies the pathos of her wretched end if we realize that by spoiling her, her father victimized her while guaranteeing the victimization of others. Amid the often outlandish set design there's surprising seriousness of purpose, or else an on-the-nose satiric impulse. But whatever message you take from it, artistically Golden Bed demonstrates how good a visual storyteller De Mille was in the silent era. We'll have a chance shortly to discuss his struggles in early talkies, but when he didn't have to worry about staging dialogue the director was, on this evidence, quite good at getting emotions on screen and finding the right images to keep the story moving and its meaning plain. His three lead actors deserve a lot of the credit. Earlier this year Rod La Rocque impressed me as the heroic idiot in The Log of the Jasper B., and now I'm more impressed by his range. Neither Lillian Rich nor Vera Reynolds had much of a career, so maybe C.B. does deserve more credit with them, but Reynolds especially is very good and seems to have deserved better than she got. So does this film; I consider myself lucky to have seen it.

Friday, November 20, 2015

My vow of silents

Usually I don't preview my viewing or reviewing plans here but I found that pun too good (?) to waste. Be informed, therefore, that up through the Thanksgiving holiday, circumstances permitting, I'll be taking a look here at a diverse range of silent movies viewed in various places. From Netflix comes The Daughter of Dawn, a recently rediscovered 1920 film shot with a Native American cast. From Troy, New York comes a new silent sci-fi featurette, When An Alien Robot Crash-Lands in Troy, NY, which I'll be seeing tonight with live musical accompaniment. Tomorrow takes me to the Madison Theater in Albany, where a Cecil B. De Mille festival climaxes with the "world premiere" showing of a George Eastman House restoration, with a new musical score, of the great showman's long-obscure 1925 film The Golden Bed. In addition to all these, I DVR-ed some early Douglas Fairbanks Sr. pictures off Turner Classic Movies last night and may have something to say about those in time. Stay tuned as the reviews come in....

Monday, November 16, 2015

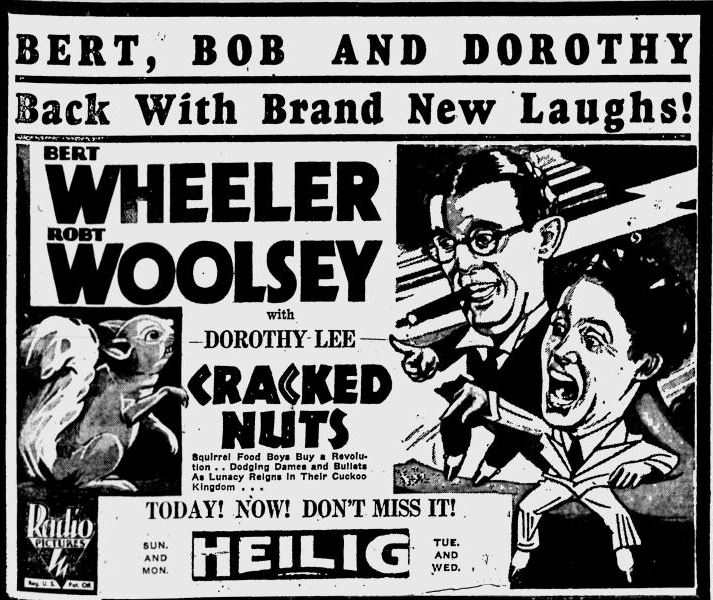

Pre-Code Parade: CRACKED NUTS (1931)

Meanwhile, unknown to Boris and the other conspirators, events in El Dorania have overtaken their plans. The king has been overthrown peacefully, having surrendered his sovereignty at a casino craps table to an American gambler (Woolsey). The stage is set for a mock-epic war of comics, who prove to be old buddies but whose claims to power are, of course, irreconcilable. Add to this the complication that Boris's conspirators and a powerful general at home intend to use whoever wins as a figurehead, and are willing to kill both once their usefulness expires, and add to that that Wheeler's girl and her aunt have followed him to El Dornaia, and he must still prove himself to them.

Why doesn't it work? More correctly, why doesn't it work now? Then, Cracked Nuts was a hit and made a profit for RKO, while Duck Soup notoriously flopped and put the Marxes' future in movies in jeopardy. With more historical context to work with, we can guess that the Marx film was seen as yet another in a soon-tiresome mythical kingdom genre that was fresher two years earlier. And that's all I've got, because I really can't imagine how anyone found Cracked Nuts funnier than Duck Soup. The Wheeler-Woolsey picture is inferior on every level. One reason why they haven't endured is that their comic personalities are shallow. The Marxes transformed themselves into iconic characters, each with a broad, intense, easily grasped persona. With Robert Woolsey in particular, you never see anything but a vaudeville comic doing his shtick. There's a fatal vibe of self-amusement when he and Wheeler lapse into practiced patter, like the scene when they find seemingly limitless ways to use the word "well" in a sentence, while the Marxes' comedy crackles with sibling rivalry and better writing. Wheeler and Woolsey never seem to do more than tell jokes self-consciously, except when Wheeler gets to sing and dance. They seem like rough drafts of better future comedians, never more so than a scene in which they compare war strategies while contemplating a map of El Dorania. The accursed nation has landmarks named "Which" and "What," among other things, and Woolsey's attempt to explain it all to Wheeler plays like a very rough draft of Abbott & Costello's "Who's On First."

Nor can Cline and his writers match the epic absurdity achieved by Leo McCarey and the Duck Soup writing team. There's no sense of larger satire here, nothing like the "We're Going to War" number or the surreal take on war-movie cliches in the Marx film. The climax of Cracked Nuts is the attempted execution of Woolsey by aerial bombing, with an unbilled, clean-shaven Ben Turpin, the cross-eyed man himself, piloting the death plane. As in many sound comedies, Turpin, apparently not trusted with dialogue, is reduced to a cameo turn in which his face is the one and only joke. The big joke of the scene is that Woolsey sneers at his fate, Wheeler having told him that he'd defused the bombs in advance, and refuses to move from his throne of doom even after live bombs start dropping. Years before, Cline had worked on Buster Keaton's early short subjects, but you wouldn't guess that from what you see here. Only a wordless sequence at the start of the picture with Wheeler waiting for an elevator hints at Cline's mighty heritage. Consider who he was working with, however. I've liked at least one Wheeler-Woolsey that I've seen, but that remains the exception. Watching them here, doing a mythical-kingdom bit, puts them head-to-head with the Marx Bros, and for that reason it also puts them in their place, however inconspicuous, for posterity.

Saturday, November 14, 2015

THE KIDNAPPING OF MICHEL HOUELLEBECQ (L'enlevement de...2014)

I've read three of Houellebecq's novels and look forward to reading Submission. Judging from the novels, you might imagine the novelist to be some intense degenerate. Many of the novels are pornographically satirical, the blatancy of the sex being part of Houellebecq's argument against the increasing commodification and increased competitiveness of every aspect of life. The advance word on Submission suggests that it's a summation of some of his career themes, especially a presumed mass yearning for a guaranteed place in the world, a refuge from competition, that Islam, among other forces, promises to fulfill. I'm actually not surprised to see Houellebecq, as imagined with his obvious cooperation by writer-director Nicloux, as an R. Crumb sort of figure, an awkward schlub seething on the inside, and on top of that a mushmouthed mumbler whom everyone asks to repeat himself. I've never seen Houellebecq give a genuine interview so I can't say to what extent he caricatures himself here, but I think, based on my incomplete knowledge of his work, that Nicloux does a good job making the author into something like a character from one of his own novels.

That doll is a perfect symbol of the banality of this particular evil

After some purposefully boring scenes of the author at home discussing redecorating, among other matters, Nicloux gets to work getting Houellebecq kidnapped. The kidnappers are a gang of three: a fat guy, a mixed martial artist and the other guy. One of them is a Roma who used to live in Israel. They're all quite aware of his celebrity; they expect a big ransom, after all, even though Houellebecq is hard-pressed to imagine who'd pay for him. One of them read his non-fiction book about H. P. Lovecraft and almost gets into a fight with him when Houellebecq denies writing that he'd purchased a pillow that had belonged to Lovecraft and had traces of his saliva. Another asks the sometime poet about poetry, and one reads him a poem he'd won an award for in school days. The fighter is eager to teach Houellebecq about MMA and the author is interested enough to learn some moves. In one of the funniest scenes he practices with the fat guy and nearly chokes him out for real despite his victim's urgent tapping out, the meaning of which Houellebecq doesn't understand at first.

Houellebecq is stashed in the home of one of the gang's parents, and the banality of his guest-room prison is a joke in its own right. The novelist soon proves himself a needy character, though the kidnappers have themselves to blame because they won't let him keep a lighter. They learn not to let him drink too much; we get hints that Houellebecq can be a mean drunk. This extended criminal family really treats their captive pretty well, even providing him with a prostitue, whom he immediately falls for. Apart from not having the lighter whenever he wants it, Houellebecq really seems to enjoy the experience, to the extent that he can enjoy anything. He gets to observe a bunch of interesting new people and, as noted, he gets waited on hand and foot. The Kidnapping becomes a kind of self-satire if you get that this relatively-comfortable captivity is the sort of submission -- some might see it as a renunciation of responsibility -- that Houellebecq's characters so often seem to long for. The punch line comes after the ransom is paid -- by an attorney representing someone he refuses to identify, though Houellebecq seems to recognize him as lawyer for suspected terrorists -- when our hero, having noticed that the family has a Polish handyman living in a storage container in their yard, notices a second container and proposes moving in. But that isn't even the final punch line. The last one is more enigmatic. After blindfolding Houellebecq and driving him out on the highway, the fat kidnapper gives him his car as his "cut" for being such a cooperative hostage. Houellebecq promptly takes him for a ride, quickly pushing the speedometer to over 250 km per hour as the erstwhile kidnapper starts to sweat. The film ends here, allowing us to wonder whether this is just a little revenge on Houellebecq's part or a hint that the novelist all along has been a more dangerous character than his captors.

It's hard to recommend The Kidnapping to general audiences despite my enjoyment of it because your enjoyment depends unavoidably on how much you know about Michel Houellebecq. So let me recommend some novels by the man, particularly The Elementary Particles and Platform. Those two should give you a sufficient idea of the man to appreciate the joke he and Nicloux are playing on himself and us.

Tuesday, November 10, 2015

DVR Diary: SLAUGHTER TRAIL (1951)

The 1950s were the golden age of the Hollywood western, marked by the flourishing of the "adult" or "psychological" western and the emergence of such master genre auteurs as Anthony Mann, Budd Boetticher and Delmer Daves. At the same time, a folkloric element to the genre persisted, finding expression in the title ballads that occasionally crowned but more often marred western movies. The three leading directors mostly avoided this balladic imperative (exceptions include Mann's Man From Laramie and Boetticher's Seven Men From Now) but the blockbuster success of both Fred Zinnemann's High Noon and Dmitri Tiomkin's title ballad convinced many a producer that ballads were essential to the western genre. The balladic imperative, an arguable inheritance from singing-cowboy films which in retrospect makes many films sound more corny than they really are, predates High Noon. At the start of the decade, producer-director Irving Allen conceived a balladic western with a sung-through narration. Slaughter Trail isn't quite a musical -- characters never "burst into song" and the major characters never sing -- but music is its life blood. Pop music is in its DNA. RKO, the studio that distributed Allen's film, hoped to exploit the participation as actor, singer and songwriter of Terry Gilkyson, who had recently written a hit song, "The Cry of the Wild Goose," that had been popularized by Frankie Laine, whose earlier hit "Mule Train" probably helped inspire many title ballads in the coming decade. However, Gilkyson did not write Slaughter Trail's title ballad, also known as "Hoofbeat Serenade." It's a tune that actually grows on you once you realize that Allen is going to stick with it all the way. Its refrain, as I remember it -- "You can only hear the sound/Of the hoofbeats on the ground/And the bandits ride around the Slaughter Trail" -- has an undeniable momentum, but some lyrics are dangerously self-referential, acknowledging that we're watching a movie "on the Cinecolor screen," or explaining how "we add tension to the plot" by introducing Indians. That doesn't match the often grimly serious action of the film, and the inconsistency of tone makes it hard to take any of it seriously.

The 1950s were the golden age of the Hollywood western, marked by the flourishing of the "adult" or "psychological" western and the emergence of such master genre auteurs as Anthony Mann, Budd Boetticher and Delmer Daves. At the same time, a folkloric element to the genre persisted, finding expression in the title ballads that occasionally crowned but more often marred western movies. The three leading directors mostly avoided this balladic imperative (exceptions include Mann's Man From Laramie and Boetticher's Seven Men From Now) but the blockbuster success of both Fred Zinnemann's High Noon and Dmitri Tiomkin's title ballad convinced many a producer that ballads were essential to the western genre. The balladic imperative, an arguable inheritance from singing-cowboy films which in retrospect makes many films sound more corny than they really are, predates High Noon. At the start of the decade, producer-director Irving Allen conceived a balladic western with a sung-through narration. Slaughter Trail isn't quite a musical -- characters never "burst into song" and the major characters never sing -- but music is its life blood. Pop music is in its DNA. RKO, the studio that distributed Allen's film, hoped to exploit the participation as actor, singer and songwriter of Terry Gilkyson, who had recently written a hit song, "The Cry of the Wild Goose," that had been popularized by Frankie Laine, whose earlier hit "Mule Train" probably helped inspire many title ballads in the coming decade. However, Gilkyson did not write Slaughter Trail's title ballad, also known as "Hoofbeat Serenade." It's a tune that actually grows on you once you realize that Allen is going to stick with it all the way. Its refrain, as I remember it -- "You can only hear the sound/Of the hoofbeats on the ground/And the bandits ride around the Slaughter Trail" -- has an undeniable momentum, but some lyrics are dangerously self-referential, acknowledging that we're watching a movie "on the Cinecolor screen," or explaining how "we add tension to the plot" by introducing Indians. That doesn't match the often grimly serious action of the film, and the inconsistency of tone makes it hard to take any of it seriously.The Slaughter Trail is where three masked bandits rob a stagecoach. One of them (Gig Young) has a laugh the victims will recognize anywhere, but one of the victims, Lorabelle Larkin (Virginia Grey) is actually in cahoots with the bandits. After her lover pretends to rough her up, Lorabelle continues with the stage to a cavalry fort presided over by Brian Donlevy, a late substitute for abruptly-blacklisted Howard Da Silva. The switch was probably for the best, except for the mistreated Da Silva, who was nonetheless one of the few character actors less plausible, as a typecast heel, in the hero's role than Donlevy himself. Meanwhile, the bandits make their getaway, stealing fresh mounts from some Navajo Indians to, as they say, add tension to the plot. The bandits, masks off, will eventually arrive at the fort, while the Navajos, then at peace with the whites, will demand that Donlevy find the bandits and surrender them to Navajo justice. Once Young betrays himself with unguarded laughter, and is recognized by the Navajos -- his gang had their masks off when they stole those horses -- a common western scenario is set up. Donlevy cares little for the bandits and seems to be falling for their moll, who herself softens in the company of the camp's children, but he must uphold the white man's rule of law against the Navajo demand for tribal justice. The fun thing about Slaughter Trail is how screenwriter Sid Kuller cares about this point of civilization only to set up the Indian attack he needs. The bandits, of course, are trusted to help fight for their lives, and they all die. Once Young goes down, the Navajos pretty much say, "We're done here" and go home. As far as we can tell they'll face no repercussions or reprisals, and Donlevy's ultimate unwillingness to enforce his principle punitively makes his earlier stand on it look silly and wasteful of both white and red lives. Yet the film doesn't treat his character as a fool. Instead, it keeps the door open for an eventual romance between the commander and Lorabelle Larkin after she rides off into the sunset for a period of penance and meditation. It's a realistically ambivalent finish at the end of a musical trail with insufferable stopovers for songs by Gilkyson and purported comedy relief from Andy Devine. His bits may have been funny when different comics first performed them ages ago, but Devine only leaves you wondering where exactly you'd seen them before. There are more minuses than pluses on Slaughter Trail but western genre buffs ought to check it out, if only because there's really nothing else like it.

Sunday, November 8, 2015

On the Big Screen: SPECTRE (2015)

Mendes can't top it. He isn't helped by the fact that two commercial campaigns have spoiled much of one of the other big scenes, a mountain chase in which Bond must pursue kidnappers downhill in an eventually wingless plane. Nor is he helped by a team of four writers who seem collectively committed to evoking or echoing many franchise highlights -- the Day of the Dead stuff is reminiscent of Live and Let Die and any mountain chase begs comparison to On Her Majesty's Secret Service -- or else to making as generic a James Bond film as possible. They made very little effort to creating truly interesting villains, failing to notice that the most interesting of them is the one who probably ranks third and last with the audience and definitely falls in that slot for writers and director. Even then, this tertiary villain -- I presume people will rank him below the Big Bad and the Oddjob-style enforcer -- is hardly an original concept. Nor is Spectre's main plot. If the previous Mendes-Craig effort, Skyfall, reminded people of Christopher Nolan's Dark Knight with its nihilist villain and his I-want-to-get-caught scheme, Spectre unavoidably echoes the Russo brothers' Captain America: The Winter Soldier with its device of an all-pervasive surveillance system promoted by intelligence agencies but promoting the agenda of a shadowy criminal organization, not to mention an antagonist from the hero's distant past.

Yes, everything has to be personal in modern genre movies, and with that mandate in mind the Spectre writers have succeeded in utterly trivializing a canonical villain. They do this despite an awesomely suspenseful intro at a conspirators' conclave, in which the banal reportage of evil achievements is interrupted by the master's arrival. The master remains in shadowy silence at the head of the table, cocking his head slightly to listen to his advisers as others at the table wait in obvious dread of whatever he may say. But then he reveals himself as Christoph Waltz and the effect is ruined. Increasingly, Waltz seems like another Michael Madsen, capable of magic when touched by Tarantino's wand but otherwise insufferable. He's the second lazy casting choice for a master villain in a row following Skyfall's recruitment of Javier (Anton Chigurh) Bardem. It didn't use to be that you had to prove yourself a master movie villain in order to play a Bond villain; doing the Bond movie actually would punch your ticket. But Mendes and his producers have been as unimaginative in their casting as they have proved cliched in their plotting. If Waltz gives a puerile performance (his catchphrase, for Gad's sake, is "coo-coo") he's only sinking to the writers' level. The motivation his character is given is an insult to the actor, the audience, and to Ian Fleming, but it's just the sort of thing writers today think profound because it's, you know, personal. If anything, the personal is the opposite of the profound in this sort of picture. And it's not as if the Spectre writers can't do impersonal, though that's no credit to them. It's one thing to waste Christoph Waltz because you're not Quentin Tarantino, but making something out of Dave Bautista shouldn't have been so tricky, and yet the writers waste him also. He was cast, if I recall right, shortly after Guardians of the Galaxy opened last year to prove what filmmakers could do by tapping into some of Bautista's amped-up wrestler's charisma. Seeing that, the Spectre team somehow could only think of him as another sort of Oddjob and allowed him a single word of dialogue in the whole picture while playing a character who's named in the credits but not in the actual movie. Bautista does as much as he can to suggest some intelligence, or at least some powers of observation, in this mute brute, but he's not that good an actor yet and, left without the sort of cool gimmick that the original Oddjob got, he ends up an oversized yet empty suit.

That leaves the third villain, the new boss of both Bond and M (Ralph Fiennes). Literally third, "C" (Andrew Scott) is the new overlord of British intelligence and a collaborator in the global "Nine Eyes" program. C and M's dialogues play out whatever passes for a theme here, the theme being that granting certain individuals license to kill is ethically superior to automated surveillance and indiscriminate drone deployment. Apparently the personal factor makes the difference, as M explains: a license to kill is a license not to kill. It sounds like an almost Orwellian paradox but James Bond presumably proves the point every time. For what it's worth, Fiennes and the rest of the Bond support team -- Naomie Harris as Moneypenny and Ben Whishaw as Q -- are the clearest pluses this time around, all improving on their Skyfall work. Fiennes in particular follows in Judi Dench's footsteps (she gets a brief video encore here) as a more active M who even gets an important fight scene of his own. They are, in fact, more appealing characters than the lead. It's hard not to read Daniel Craig's now-infamous comments, since partly contradicted, about preferring suicide to continuing in the role into the role as he plays it in Spectre. He breathes life into a few quips but seems indifferent if not contemptuous toward the "personal" storyline linking Bond to Waltz's villain, while his required romances are by-the-numbers stuff. Whether he changes his mind about continuing or not, it may be time for EON Productions to be rid of him, if not the whole creative crew of his series, so we can have a true 21st century Bond who brings the appropriate enjoyment to his 21st century work. The three previous Craig pictures and the writers' dogged insistence on continuity trail and drag Spectre the way that little train of barrels handicaps Bautista's villain at a crucial moment. You can tell that Spectre was meant as some sort of celebration of all the things that make Bond pictures distinctive, but the result looks like an official pastiche if not a self-parody. It's still acceptable as a mindless popcorn movie with some good action scenes, but despite its pretensions it's nothing more than that.

Friday, November 6, 2015

A GIRL WALKS HOME ALONE AT NIGHT (2014)

Ana Lily Amirpour was born in Great Britain and considers herself Iranian-American. To my knowledge, she's never set foot in Iran, yet she has made a movie in her ancestral Farsi and planted Farsi street signs on her southern California locations. Are we supposed to believe that it's taking place in Iran? Is it in some way a reflection on the Islamic Republic? Or is it just weird for the sake of weird? My last guess is probably the best one. Amirpour's "Bad City" is a dystopia -- there seems to be a municipal dumping ground for dead bodies near some busy roads -- but there's nothing oppressively Islamic about it. Instead, there's the blasphemy at the heart of the picture: under the chador that signifies modesty and obedience a vampire (Sheila Vand) stalks the city. This nameless vampire seems stuck in eternal late adolescence, happily claiming a skateboard as tribute from a frightened child. Apparently she was turned in the early 1980s, to judge from the music posters in her lair. That's nearly contemporary with the advent of the Islamic Republic, but maybe Amirpour just likes the music and fashions of that era. Apart from the vampire's mocking chador and the fact that everyone talks Farsi, Bad City looks pretty much like the America where the film was shot, complete with a hapless hero (Arash Marandi) with a leather jacket and a convertible to drive through the Lynchian industrial landscape.

Ana Lily Amirpour was born in Great Britain and considers herself Iranian-American. To my knowledge, she's never set foot in Iran, yet she has made a movie in her ancestral Farsi and planted Farsi street signs on her southern California locations. Are we supposed to believe that it's taking place in Iran? Is it in some way a reflection on the Islamic Republic? Or is it just weird for the sake of weird? My last guess is probably the best one. Amirpour's "Bad City" is a dystopia -- there seems to be a municipal dumping ground for dead bodies near some busy roads -- but there's nothing oppressively Islamic about it. Instead, there's the blasphemy at the heart of the picture: under the chador that signifies modesty and obedience a vampire (Sheila Vand) stalks the city. This nameless vampire seems stuck in eternal late adolescence, happily claiming a skateboard as tribute from a frightened child. Apparently she was turned in the early 1980s, to judge from the music posters in her lair. That's nearly contemporary with the advent of the Islamic Republic, but maybe Amirpour just likes the music and fashions of that era. Apart from the vampire's mocking chador and the fact that everyone talks Farsi, Bad City looks pretty much like the America where the film was shot, complete with a hapless hero (Arash Marandi) with a leather jacket and a convertible to drive through the Lynchian industrial landscape.

A skateboarding vampire symbolizes eternal youth pretty nicely,

but even eternal youth grows dated in time.

Amirpour calls her film an "Iranian vampire spaghetti western." Check, check and .... well, no. Let's draw a line somewhere. That label really only underscores the movie-movieness of A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night. The Iranian-ness of the characters and dialogue and the genuine inspiration of the menace under the chador -- has Amirpour been accused of inflaming Islamophobia? -- only superficially covers the essentially derivative nature of the movie, giving it a pretentious novelty. Yet there is something sincere in her empathetic approach to her alienated protagonists groping toward intimacy amid squalor and danger. The vampire girl still longs for human company, for friends if not lovers whom she doesn't have to devour. There are plenty of people left over for that purpose: the pimps, the junkies and other dregs of society. Her victims eventually will include the hero Arash's father, but the father's addiction, fed by the pimp, has made Arash's life hell, if not more of a hell than life in Bad City is for anybody. Under more normal circumstances this killing might turn our hero against his undead friend, but in fact it's the moment that allows them both to cut their ties with the accursed place.

There's a slight echo of Let the Right One In/Let Me In in this creepy courtship, though A Girl Walks Home is ultimately more romantic, its vampire more in need of a soulmate than a servant. She sees something more in Arash than initially meets the eye when she finds him in a Dracula costume, having staggered stoned from a costume party, staring at a streetlamp. I don't think she's dumb enough to have though he might be like her that way, but she does seem to sense that he's like her in some way. She feels a similar sort of kinship with a prostitute who seems as much a victim of life as Arash, abused by the same pimp who claims our hero's convertible as payment for dad's drugs before the vampire kills him and manhandled by the dad (who has a past with her) until the vampire kills him. People like Arash and the hooker are the closest she'll get to the underworld of sociability with which most American vampires are blessed these days. In that sense, depending on your preferences, A Girl Walks Home is more of a proper vampire movie than many made these days, or at least more of a horror film than those fantasy films, even if it's still too romantic, in its despairing way, for some tastes.

Welcome to Bad City

It's a pretty slick piece of work, thanks largely to Lyle Vincent's black and white cinematography. If there's anything "spaghetti" about the picture its Amirpour and Vincent's proficiency in widescreen composition. It's mercifully light on effects, as Vand's vampire displays quite modest fangs and gets her voice mechanically modulated when she wants to scare people. Overall, it reveals Amirpour as a talent, but it seems just a little too calculated a revelation. It's paid off just the same, since she'll have an English-language cannibal movie with real stars out next year. Let's wait for that one before we say that Amirpour is really a talent to watch. For now she's done enough to get a second chance.

Monday, November 2, 2015

JAUJA (2014)

Mortensen plays Gunnar Dinesen -- is there a homage to Karen "Isak Dinesen" Blixen of Out of Africa fame there? -- an engineer and advisor to the Argentian army, apparently concerned above all with keeping his daughter (Viilbjørk Malling Agger) away from that wanker and other soldiers. His efforts avail him not, as Ingeborg elopes with a younger, better looking soldier. We're in Searchers territory once Dinesen heads out alone in pursuit of the couple, with all three in danger from renegades. Gradually it seems to become a different kind of quest, or else a different kind of story altogether.

Alonso's neo-primitivist storytelling leads you to believe that Jauja is some sort of naturalist narrative, but all along there's something almost too quaint about it. It could be the curved corners of the old-timey 1:33 aspect-ratio frame, which made me think of 19th century photographs. Maybe there's something too obviously archetypal about it, apart from the most obvious Searchers references. And maybe a spoiler warning is in order, since at a certain point, when Dinesen encounters an old woman in a cave, Alonso's tale becomes something more like a dream, or a blood memory half-recovered in a dream. The film ends far in time and place from Patagonia, but the message seems to be that dreams, myths or archetypes can transcend distance, or else that the distance between present and past, or history and dream. is even less. You can complain that this takes you right out of the picture, if you wanted to know what happened when Dinesen caught up with his daughter. But maybe a point is being made about your offended sense of linear time when a film finds reason to remind you that it's only a film, and all of it only fiction. You may try to reclaim some sort of linearity by figuring out who the girl in modern dress is, and the director himself leaves clues that point to the relevance of the Dinesen story to the present-day epilogue. But there's no denying that Jauja is the sort of film that will leave people asking "Is that it?" in way that questions whether there was ever an it to it. I suspect that there is an it to it after all, but I'm not sure yet whether there's enough of it to justify the tease that Jauja perpetrates. There's still the beautiful cinematography, the admirably laconic direction, and a fine, fully committed physical performance from co-producer Mortensen, and the twist, if you want to call it that, doesn't take any of that away. Watch the film for those, and judge the rest for yourselves.