Tragedy is sometimes just a matter of timing. The tragedy of Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle is that he died in the middle of rewriting his tragic narrative. A heart attack claimed him at age 46, reportedly on the very day in 1933 that Warner Bros. signed him to a feature-film contract. Arbuckle had already finished Stage One of his comeback from an exile imposed on him despite a most emphatic acquittal after his third manslaughter trial for the death of Virginia Rappe. Merely to have taken part in the wild party where Rappe took ill, it seems, had been enough to justify making an example of Arbuckle at a time when Hollywood had been rocked by its first serious moral scandals. Like future blacklisted talent, Arbuckle never fully disappeared from the entertainment business. He performed in vaudeville and on Broadway, and returned to Hollywood to direct movies under a pseudonym. It seems right that he was called back before the camera during the Pre-Code era, but Arbuckle's six Big V shorts for Warners aren't really Pre-Code pictures in the salacious sense. You can divide them between nostalgic knockabouts in Arbuckle's old style (particularly How've You Been?, in which Fatty wastes his already-limited grocery store stock mindlessly hurling sacks of flour at a suspected criminal) and forays into contemporary nut comedy. I happen to like the nuttier films the best, but they're also the shorts in which Arbuckle most seems like an interchangeable part in the Big V machine.

Comedies like Close Relations and Tomalio (the latter finished the day before Arbuckle died) are more ensemble pieces than star vehicles, though Arbuckle's face fills the title cards. Big V had an eclectic stock company that included Shemp Howard (who must have had the longest hair on a Hollywood man at the time) a young Lionel Stander and the studio's most underrated comic, Charles Judels. With a range from the amiable to the apoplectic, Judels' signature was a closed-mouthed whine like a whistling kettle. Playing a psychotic Latin American general who can summon a firing squad to any location with his trusty whistle and insists on hearing the Lohengrin overture during executions, whether on a jukebox or performed by a three-piece band, Judels pretty much steals Tomalio from Arbuckle, who with his Kansas accent never sounds more like Oliver Hardy than in that short's clever opening shot. Fatty is shown in close-up sitting in the middle of the desert, angrily asking an unseen interlocutor, Hardy-style, "Why don't you help me?" The camera pulls back to indicate that Fatty is talking to a mule. Then we hear another voice, and the camera pulls further back to reveal that the mule is sitting on Fatty's sidekick for the picture. These shorts mostly have nice production values, though several opt for cheap animation effects to portray insect attacks or eruptions of Mexican jumping beans across a dinner table. They seem state of the art otherwise, but Arbuckle himself, however good-natured, seems old-fashioned in his standard costume with high-water pants and a voice that marks him as an oldschool rube. He still has some of his physical skills, best displayed in his juggling of kitchen implements and ingredients in Hello, Pop!, though he doesn't take the truly epic bumps he did in his youth. For that matter, the films themselves often flinch from large-scale destruction, usually setting up a violent collision, then cutting to someone's reaction shot before showing us the wreckage. It's an odd quirk that doesn't really harm the films very much.

Watching the Arbuckle shorts in a Warner Archive Big V collection was a nostalgic experience for me. I remember long long ago seeing In the Dough played in the wee hours on The Joe Franklin Show, at a time when I knew about Fatty Arbuckle but not about his Vitaphone shorts. Seeing him talk on screen late that night was like looking into an alternate reality. While I found all the shorts are all fairly entertaining -- Tomalio, Close Relations (Fatty is named an heir to a fortune but discovers his uncle [Judels] is a gouty lunatic) and Buzzin' Around (Fatty invents a shatterproof coating for ceramics but takes a jar of hard cider to town for the demonstration by mistake) are the best -- they do leave you wondering how much further Arbuckle might have gone had he lived. He was probably at the right studio, Warners being the home of Joe E. Brown, another exemplary physical comedian. Brown occupied his own separate universe at Warners, his films arguably more kiddie fare than the studio's typical Pre-Code product, and you can imagine Arbuckle making features in a similar sphere. Would we have seen Fatty among the comics in A Midsummer Night's Dream, or grappling with such absurdities as Sh! The Octopus? Would Warners have given him a chance in more adult fare, possibly as a younger version of Guy Kibbee? Or would Arbuckle have ended up making crap at Columbia alongside his great friend Buster Keaton by the end of the decade? Or would the backlash that led to Code Enforcement drive him from the screen again? The real tragedy of Fatty Arbuckle is that we can't know. His story ends all too abruptly on what he reportedly called the best day of his life.

A randomly comprehensive survey of extraordinary movie experiences from the art house to the grindhouse, featuring the good, the bad, the ugly, but not the boring or the banal.

Wednesday, November 30, 2016

Sunday, November 27, 2016

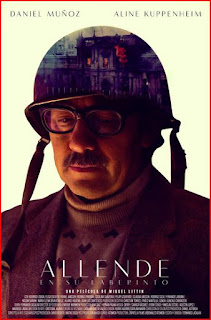

ALLENDE (Allende en su laberinto, 2014) and THE BATTLE OF CHILE (1975-9)

Santiago, Chile: September 11, 1973

Allende was the rare Marxist to win power by election, and wanted to prove that socialism could be achieved by peaceful means. Guzman's three-part documentary (I've only seen the two parts aired on TCM last week) is subtitled "the struggle of an unarmed people" and from all appearances the deck was stacked against Allende and his movement. Allende did not win a majority of the popular vote in 1970 -- he led the three-candidate field with approximately 36% -- and was chosen by the country's senate. But his fate was sealed almost from the start by the fact that his Popular Unity coalition never won control of the Chilean legislature. Conservatives and relative moderates could block many of his initiatives, but in turn they never had enough votes to impeach Allende. As Guzman stresses at every opportunity, the U.S. (under Nixon and Kissinger) opposed Allende from the beginning and provided both moral and material support to both the legal and the military opposition. The coup that toppled Allende was the second attempt of 1973, following a small but lethal uprising by a rogue unit that June. The first part of Guzman's documentary closes with ultimately dramatic footage of these soldiers firing directly at a cameraman as that brave man films his own murder. The anti-Allende majority in the legislature refused to declare a state of emergency after the coup, denying Allende the power to purge the military and other institutions, while many in Chile felt that Allende himself had far overstepped his constitutional bounds. The latter viewpoint is not taken seriously by Guzman and isn't addressed at all by Littin, and watching these films only launched me into a labyrinth of history without guiding me to the end.

The Littin film focuses exclusively on Allende's last day and presumes knowledge that only Chileans or specialist historians outside that country will possess. So I recorded the Battle episodes to get more context, and while Battle of Chile is a powerful piece of documentary propaganda it begged as many questions, if not more, as it answered. While I can't believe that a military coup or Allende's death -- the consensus is that the president killed himself as troops stormed the palace -- were justified, constitutional objections to his measures or his alleged refusal to abide by high-court rulings against him can't just be dismissed as the dishonest carping of conservative or bourgeois "mummies." Nor can I dismiss workers who went on strike in 1973 as stooges for the "mummies" as readily as Guzman does, no matter what damage they did to the Chilean economy and Allende's position. Guzman seems satisfied that Allende was always within the constitution because he was the duly elected president, and he refers to Allende's supporters as "constitutionalists," but Battle refuses to engage constitutional questions objectively. You could believe from Guzman, if not from Allende himself, that a constitutional election only provided a pretext for an extra-constitutional transformation of society. Allende deserves a fuller treatment of his character -- and may have gotten it in a 2004 documentary -- then either film gives him. Littin doesn't give us much sense of what he stood for other than occasional remarks about "comrades" and "workers." The main thing I got from Littin's film was that Allende chose death over exile to deny the coup plotters and the eventual dictatorship -- Augusto Pinochet was military chief of staff at this time and Littin shows Allende repeatedly asking where Pinochet is until he learns that the supposedly loyal general is leading the coup -- any pretense of legitimacy via a peaceful handover of power. In that sense Allende lost the battle of La Moneda but won the battle of history, at least on film. But while Battle is a fascinating film that also seems eerily prophetic of the polarization of the 21st century U.S. in its man-on-the-street interviews and clips from Crossfire-style TV shows, and Allende can't help but be dramatic, my real recommendation is that you find some reputable, nonpartisan book for the real story.

Monday, November 21, 2016

Too Much TV: A note on TV westerns

It looks like I won't have much time for this blog this week -- holiday deadlines do that to me -- but I wanted to let readers know that after a couple of years of somewhat intensive viewing I'm about ready to start doing series reviews of some classic western series from the 1950s and 1960s. TV westerns are a relatively late enthusiasm of mine, rather like pulp fiction and probably for some of the same reasons. I didn't care much for westerns when I was a kid, when what I had for reference was Bonanza, a show I've never warmed to, and the last seasons of Gunsmoke. It was unfair of me, I know now, to judge the genre by these shows, but only in recent years have I been able to see a larger sample of shows, thanks to cable TV. The premium channel Starz Encore Westerns, the Christian channel INSP, and channels of the sort used by local network affiliates to fill their digital slots -- MeTV, GetTV and Grit in particular -- have made a wider range of westerns available than we've had in thirty or forty years. In the past you'd see Gunsmoke and Bonanza because those were the longest-lasting shows. Now you can see shows that lasted only three or four years, or even one or two. Some deserved to last longer while some, of course, deserved their quick demise. I've seen enough now to know what I like and, I think, to know what's good. In general I like these shows for their tremendous stock company of character actors, some of whom moved on to movies (Charles Bronson, Warren Oates, George Kennedy, etc.) while others remained TV stalwarts (John Dehner, Claude Akins, John Anderson, etc.). I also like the efficiency of their storytelling, their ability to tell a complete story in an hour or half an hour. While there's much to be said for the modern immersive longform series, there's a sense of satisfaction from seeing a story complete in one sitting, without binging, that the modern shows, for all their virtues, can't provide. It was easier to tell complete stories quickly because the old shows didn't focus on an ongoing evolution of their heroes. That might sound bad at first hearing, but the idea usually was that we encountered characters already fully evolved, as opposed to today's concern with how everyone begins. The older shows weren't distracted by shipping, either. While I don't deny the entertainment value of shipping, the old arrangement that doomed every relationship a protagonist got into -- a love interest might die but more often simply moved on -- seems more like life somehow in its commitment to transience. I don't know what most people think when I raise the subject of classic TV westerns, but the best of them were clear kin to the "adult" or "psychological" westerns that flourished in the Fifties, and the necessity of cutting off all storylines but the protagonists' at the end of each episode often took these westerns in very dark directions. Some 1965-6 episodes of The Virginian, for instance -- that long-lived series' darkest season, that almost killed it -- might not seem out of place on HBO fifty years later, a lack of gore notwithstanding. It isn't darkness I'm looking for in the best western shows, however. I'm looking for a certain laconic authenticity and gravitas absent in both the more garrulous or simply goofy shows and the more stylized or gimmicky spaghetti westerns to which the classic TV westerns are often unfavorably compared. I'm also looking for heroes who kick ass and -- this is important -- talk the talk as well as walk the walk. I've found a few of those in my western watching, and I hope to introduce some of them to you sometime soon.

Thursday, November 17, 2016

THE LAST KING (Birkebeinerne, 2016)

On the snowy slopes of thirteenth century Norway, warriors on skis must have traveled faster than any man could without the aid of a horse. Their speed lends a thrilling novelty to Nils Gaup's compact epic, which admirably gets a big job done in little more than 90 minutes. Gaup is on somewhat familiar ground, having made his name globally with the similarly set 1987 film Pathfinder. In Birkebeinerne (the Last King title doesn't seem relevant to the story) it's 1206 or thereabouts and Norway is torn between two powerful factions, the titular good guys ("birchlegs" in some translations) and the bad guy Baglers. For an outsider it's hard to tell what each party stands for, though there's an interesting anticlerical angle in the film's emphasis on the Baglers' alignment with the Vatican that's underscored by a Birkebeiner's scoffing attitude toward prayers over a wounded ally. Suffice it to say that the poisoning of a young king puts the Baglers' man in power, but a mere baby boy has a more legitimate claim. It's up to the Birkebeiners to keep the baby safe while they try to raise an army in his name. The child's location is confided to Skjerveld (Jakob Oftebro), but the Baglers are on to him. They threaten his wife and his own small child with death unless he confesses where the baby king has been hidden. Skjerveld cracks, only to be mocked by the Bagler commander for having less fortitude than his wife, whom the commander orders killed out of pure spite.

Skjerveld, aided by his buddy Torstein (Kristofer Hivju), now has a twofold mission of revenge for his family and redemption for himself. Only a Bagler attack saves him from execution after he admits his betrayal, but he and Torstein take the baby to the next safe house, with the big-bad Bagler commander in hot pursuit. The chase scenes are exhilarating in an almost anachronistic way, since we still expect James Bond, not some furry medieval man, doing this sort of thing.

Our heroes finally patch together a little army that should be enough to ambush the Baglers as they fall into a trap baited with the baby king on a sled. The movie exposes its budgetary limitations in the big attack, although I suppose that a mere handful of ski-jumping warriors could well wreak havoc on a conventional horseback army. In any event, the final battle is nicely plotted to set up a redemptive showdown between Skjerveld and the Bagler commander, the last of the one band of bad guys to escape the trap and threaten the little king. It's all based on fact, although I read that Norwegian historians unsurprisingly found the film's version of events oversimplified. Birkebeinerne is no masterpiece, but it's cool to get a decent action film that comes with a history lesson to broaden your knowledge of the wild world of cinema.

Sunday, November 13, 2016

On the Big Screen: ARRIVAL (2016)

It's nice to see Hollywood spend some money on science fiction that isn't space opera, but it's not as if "first contact" isn't a familiar subgenre already. The really good thing about Dennis Villeneuve's film is how it problematizes that contact and explains the problems involved in comfortably dramatic fashion. We start with twelve contact lens-shaped alien ships appearing in apparently random parts of the world, including Montana USA. An Army colonel (Forest Whitaker) invites linguist and translator Louise Banks (Amy Adams) to interpret what the seven-limbed creatures (their vaguely cthulhoid appearance keeps our guard up) have tried to say so far. The colonel wants to cut to the chase and find out why the Heptapods are here, but Banks explains quite clearly how the building blocks of conversation have to be assembled before we can ask the colonel's question in comprehensible fashion. Quickly concluding that talking to the Heptapods may be impossible, Banks starts to teach them written English, and in turn learns the Heptapod language, written with natural ink in circular, distinctively blotted sentences that hang in the creatures' thick atmosphere or stick to the glass partition separating them from the humans. This allows the beginnings of communication, but specific meanings of "words" still need to be nailed down before false conclusions are drawn. In the most obvious case, the Heptapods seem to be saying that they're here to "offer weapon" to the different countries they're visiting -- including not just the U.S. but China, Russia, Pakistan, etc. -- and urging us to "use weapon." Are they really talking about a "weapon," and what do they mean by using it? The authoritarian countries, somehow led by a Chinese general rather than a party secretary, conclude that the Heptapods are hostile and prepare for military action. American instincts are along the same lines, but Banks bucks authority, backed by sympathetic physicist Ian Donnelly (Jeremy Renner), to get crucial clarification from the Montana Heptapods they've nicknamed, in a nod to cinematic language games of the past, Abbott and Costello....

I want to be more careful about spoilers with Arrival than I am with superhero films that, as components of larger projects, may only be comprehensible in contexts established by spoilers. Arrival happily stands alone and deserves to have the integrity of its surprises respected. I'll tease rather than spoil by warning you that the film toys with certain movie conventions in a manner that first seems disappointingly derivative -- one particular attempt at character development will seem to have been ripped off blatantly from another recent sci-fi film with a female protagonist -- but gains fresh meaning once the story resolves itself. I'm not sure I entirely comprehend the full story -- it's unclear to me whether an important attribute of the heroine is acquired or innate, though I lean toward the former -- but in this case, at least, that doesn't mean the picture is incomprehensible. While its portrayal of military-intelligence types is pretty cliched, Arrival overall is a film that respects your intelligence and deserves respect in return. Villeneuve directs in a classic widescreen style, with cinematography by Bradford Young, and even if it's not a space opera it's often spectacular to look at. I'm not ready to anoint Amy Adams an Oscar front-runner, but I appreciate why people appreciate her work as a character defined primarily by brains and I can't honestly say I've seen much better acting this year. It's nice to see her in an alternate universe she can share with Jeremy Renner (see also American Hustle) when their regular "cinematic universe" haunts are off-limits to each other. In a way, that makes the world of Arrival more real, no matter how fantastic a story it tells.

I want to be more careful about spoilers with Arrival than I am with superhero films that, as components of larger projects, may only be comprehensible in contexts established by spoilers. Arrival happily stands alone and deserves to have the integrity of its surprises respected. I'll tease rather than spoil by warning you that the film toys with certain movie conventions in a manner that first seems disappointingly derivative -- one particular attempt at character development will seem to have been ripped off blatantly from another recent sci-fi film with a female protagonist -- but gains fresh meaning once the story resolves itself. I'm not sure I entirely comprehend the full story -- it's unclear to me whether an important attribute of the heroine is acquired or innate, though I lean toward the former -- but in this case, at least, that doesn't mean the picture is incomprehensible. While its portrayal of military-intelligence types is pretty cliched, Arrival overall is a film that respects your intelligence and deserves respect in return. Villeneuve directs in a classic widescreen style, with cinematography by Bradford Young, and even if it's not a space opera it's often spectacular to look at. I'm not ready to anoint Amy Adams an Oscar front-runner, but I appreciate why people appreciate her work as a character defined primarily by brains and I can't honestly say I've seen much better acting this year. It's nice to see her in an alternate universe she can share with Jeremy Renner (see also American Hustle) when their regular "cinematic universe" haunts are off-limits to each other. In a way, that makes the world of Arrival more real, no matter how fantastic a story it tells.

Friday, November 11, 2016

DVR Diary: THE WORLD'S GREATEST SINNER (1959-62)

Timothy Carey may be best known to movie buffs as the tall crybaby French soldier doomed to execution in Stanley Kubrick's Paths of Glory. Some with different tastes may recall him as South Dakota Slim from the AIP beach party movies. Carey seems to have been some sort of crackpot, so it should come as no surprise that when he resolved to produce, write, direct, star in and distribute his own movie, it should be a film about a megalomaniac. Making the picture was a long act of pure will by the aspiring auteur, and its subject is a man who seeks to live and transform the world through sheer will. Clarence Hilliard is a sales manager for an insurance company, apparently happy with his bourgeois life with wife, daughter and horse, but the Devil (voiced by Paul Frees) is watching. Hilliard sells life insurance, but has grown tired of talking about death, tired of others thinking about death and building their lives around it. His mounting mania gets him fired, but that only frees him up to take up his new calling as a prophet preaching a new populist religion in which every man is a god, or at least a Super Human Being. Improbably, Hilliard builds a following preaching on the streets, drawing disciples with the promise that you can become a god by saying you are. Mesmerized by a rock concert, Hilliard reimagines himself as a "rock god" with a gold lame jacket, a fake soul patch and volcanic Elvis moves -- the shambolic Carey looks like he's going to erupt out of his clothes as he jackhammers across the stage to the music of Frank Zappa. Now that he's God Hilliard, the next natural thing is to run for President, promising to mobilize science and medicine to make Super Human Beings a reality. His appeals to the forgotten common man, uttered by a charlatan high on his own supply, have a fresh prophetic resonance now, nearly sixty years after Carey shot the film. Godhead has a price, however, as Hilliard's wife rebels against his divine ways with other women, young and old, and his apparent rejection of the real God. Hilliard doesn't want to be bothered by her petty protests, but he is bothered when she leaves him. Her departure provokes a crisis of faith in himself that can only be resolved by challenging the God of the Eucharist, incarnate in a consecrated wafer.

Just as in many a monster movie, holiness actually prevails, but it's hard, even in that light, to see Sinner as a tract against the demonic ambitions of God Hilliard. As in many monster movies, you're probably supposed to root for the monster, though Carey, admittedly charismatic in his own eccentric way, does everything in his power to make Hilliard repulsive. What's compulsive, and compelling, about the picture is how transparently the morality tale gives Timothy Carey a platform to act out on, to play the rock star, the preacher man, the demagogue. The World's Greatest Sinner is aueturism as shameless exhibitionism. It's one of cinema's greatest ego trips, though Carey tries to art it up in various ways that only emphasize his rawness as a filmmaker, e.g. leaving the reel ends in the finished (?) picture. Amateurish in many ways, it's elevated by Carey's own talent as a performer and by young Zappa's genuinely effective score -- though the great man dismissed the picture as "the world's worst movie." Somehow I don't think Carey took offense; it was a superlative after all, and it meant he had done something memorable.

The Last of the Seven

Robert Vaughn died today at age 83. As noted above, he was the last surviving title character from John Sturges' 1960 film The Magnificent Seven, a loose remake of Akira Kurosawa's Seven Samurai that was itself loosely remade this year. Before that film Vaughn had played a range of troubled juveniles, from the baby-faced killer in the western Good Day For a Hanging to the title character of Teenage Caveman. With a high-profile role in the Sturges film following an Academy Award nomination for The Young Philadelphians Vaughn seemed on the path to movie stardom, but TV was still where the consistent money was for the young actor. He lasted a year on The Lieutenant before landing the gig he'll be remembered for as Napoleon Solo on The Man from U.N.C.L.E. That should have been a springboard to movie stardom but before long Vaughn was back on TV, this time in Great Britain as one of The Protectors. From there it was back and forth between TV, where his name still had some prestige, and increasingly schocky movies. He was stunt-cast as a judge in a Magnificent Seven TV series, and at a low ebb you could see him plugging local law firms on cable TV, but did his most substantial work during the 21st century back in Britain, as a mentor to con artists in the Hustle show. People who watched it tell me it was redemptive work for Vaughn, to an extent. He probably never got as far ahead in Hollywood as he hoped, but he did end up a sort of pop-culture icon.

Tuesday, November 8, 2016

Too Much TV: WESTWORLD (2016-?)

For cable series with short seasons (13 episodes or less) I've tried to wait until after a season is over to write a review, but in Westworld's case an uncertainty about what the hell is going on is such an essential element of the show that I feel entitled to write something now, with only six episodes aired so far. HBO's long-in-the-works series is a radical revision of Michael Crichton's 1973 movie, the author's first imagining of a high-tech theme park where nothing could possibly go wrong ... go wrong ... go wrong...Anyway, it follows in the footsteps of the Battlestar Galactica reboot by vesting its androids with personalities, and goes further by making them the most sympathetic characters on the show. As reimagined by Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy, with significant input from J. J. Abrams, Westworld is a vast playground where guests can take part in storylines with highly interactive "hosts," each with its own backstory. The guests pay huge sums for the ultimate privilege of using the hosts however they please. They can play along with the established storylines and be heroes, or they can go "blackhat" and kill, rape or otherwise the hosts with virtual impunity. Atrocities are routine, but every time a host is "killed," it's taken to the shop to have its body repaired and its memory purged, and then sent out to start its story over. Behind the scenes, employees battle for creative control of the storylines, and sometimes exploit the hosts in quasi-necrophiliac fashion. Ruling over it all is the perhaps too blatantly named Robert Ford (Anthony Hopkins), the co-creator of Westworld who now theoretically answers to the Delos Corporation but seems to do as he damn well pleases regardless of heavy monetary losses and pressure from the Delos board to deliver new storylines.

We'd have no show if nothing went wrong, and the problem evolving as we arrive is that some hosts are starting to remember the traumas they've suffered. A line of Shakespeare, "These violent delights have violent ends," seems to be a trigger phrase activating deeply hidden protocols in the remaining first-generation hosts, thirty years after Westworld's opening was marred by the death of Ford's partner, a man we know only as Arnold, who has loomed ever larger as the series progresses. Two hosts serve as our point-of-view characters to these changes. They represent opposed western archetypes: the rancher's daughter Dolores (Evan Rachel Wood) and the whorehouse madam Maeve (Thandie Newton). Dolores got the trigger phrase from the host that played her father, and gave it to Maeve almost at random. Both hosts relive brutal attacks as dreams, and both seem to be victimized by the so-called Man in Black (Ed Harris), apparently a philanthropist in real life but a sadistic superman in Westworld. A regular if not addicted guest, the Man in Black has mastered the system so that he's virtually invincible, but continues hunting for hidden levels. He seems to believe that Westworld has not lived up to its potential and seeks to awaken that potential through extreme violence and cruelty to the hosts. He has a privileged status at Westworld ("That gentleman gets anything he wants," one staffer says), and why that should be is one of the show's most compelling mysteries so far. He now hopes to discover a maze that may be Westworld's ultimate level. For the hosts the maze is an Indian myth, but it may be something more than that. "The maze is not for you," one tells the Man in Black, and it may be for the hosts; a test they can undertake with a hint of true freedom at the end.

Dolores seems headed for the maze, accompanied by two corporate guests, one striving to be a good guy, the other a practiced blackhat. She's coached by a voice in her head that has enabled her to override the programming that prevents hosts from harming living creatures. She's also coached in a different way by one of Ford's top aides, Bernard Lowe (Jeffrey Wright), who breaks one of Ford's personal rules by interviewing a fully-clothed Dolores. Ford prefers that the hosts go naked in the shop to discourage the staff from humanizing them, though he has a sentimental mockup of his own family, including a host version of himself as a child, in an isolated location in the park. Dolores and the Man in Black seem to be on a collision course, unless you buy into the popular fan theory, perhaps inspired by NBC's nonlinear family drama This is Us, that their storylines are actually happening many years apart. Meanwhile, Maeve seems to be figuring things out for herself without the same coaching Dolores gets. She remembers waking up accidentally and seeing the inner workings of Westworld, remembers being shot despite having no scar where the wound should be, and cuts herself open to find a bullet staffers had forgotten to remove. Piecing these details together, she starts getting herself killed deliberately in the hope of waking up in the shop again, and eventually gets her wish. Now, while Dolores continues to blunder toward her destiny, Maeve blackmails some Westworld staffers into explaining how she functions and upgrading her for purposes that remain to be seen. While all this is happening there's evidence of corporate espionage inside the park, and increasing evidence that Arnold hasn't had his last word yet on the future of Westworld and its hosts....

Much of what I could say about Westworld right now remains speculative, but for genre fans that's part of the fun of the show. The show is a kind of mystery or puzzle in which speculation is essential to the experience; if you're impatient for explanations it won't be for you. The game-like nature of the show extends to its soundtrack, which each week challenges you to identify the contemporary rock tune being covered on the player piano in Maeve's brothel. The show exists, as my mom used to say when we asked why too often, to make you ask questions. Who is the Man in Black? How did Arnold actually die, if he's actually dead? Who among the guests or staff might actually be hosts? Any show can beg questions like this, but Westworld's writing and acting make the questions worth asking and trying to answer. When Hopkins first appeared, I thought dismissively that he'd become the rich man's Malcolm McDowell, but he seems to be on his game here, while Harris makes an evilly enigmatic Man in Black. Wood and Newton are the real stars here, as well as our surrogates as seekers after the truth of Westworld, In their contrasting quests they seem more human than human, given the despicable nature of so many human guests in this decadent playground. But there are plenty of sympathetic humans as well -- presuming that they're human, of course. The mysteries of Westworld give the show an expansiveness beyond its massive budget. My worry is that once its mysteries are resolved it will lose a lot of its mystique. It may be better not to know enough than to know too much, but only time will tell one way or another. For now, it's my favorite new show of the fall.

We'd have no show if nothing went wrong, and the problem evolving as we arrive is that some hosts are starting to remember the traumas they've suffered. A line of Shakespeare, "These violent delights have violent ends," seems to be a trigger phrase activating deeply hidden protocols in the remaining first-generation hosts, thirty years after Westworld's opening was marred by the death of Ford's partner, a man we know only as Arnold, who has loomed ever larger as the series progresses. Two hosts serve as our point-of-view characters to these changes. They represent opposed western archetypes: the rancher's daughter Dolores (Evan Rachel Wood) and the whorehouse madam Maeve (Thandie Newton). Dolores got the trigger phrase from the host that played her father, and gave it to Maeve almost at random. Both hosts relive brutal attacks as dreams, and both seem to be victimized by the so-called Man in Black (Ed Harris), apparently a philanthropist in real life but a sadistic superman in Westworld. A regular if not addicted guest, the Man in Black has mastered the system so that he's virtually invincible, but continues hunting for hidden levels. He seems to believe that Westworld has not lived up to its potential and seeks to awaken that potential through extreme violence and cruelty to the hosts. He has a privileged status at Westworld ("That gentleman gets anything he wants," one staffer says), and why that should be is one of the show's most compelling mysteries so far. He now hopes to discover a maze that may be Westworld's ultimate level. For the hosts the maze is an Indian myth, but it may be something more than that. "The maze is not for you," one tells the Man in Black, and it may be for the hosts; a test they can undertake with a hint of true freedom at the end.

Dolores seems headed for the maze, accompanied by two corporate guests, one striving to be a good guy, the other a practiced blackhat. She's coached by a voice in her head that has enabled her to override the programming that prevents hosts from harming living creatures. She's also coached in a different way by one of Ford's top aides, Bernard Lowe (Jeffrey Wright), who breaks one of Ford's personal rules by interviewing a fully-clothed Dolores. Ford prefers that the hosts go naked in the shop to discourage the staff from humanizing them, though he has a sentimental mockup of his own family, including a host version of himself as a child, in an isolated location in the park. Dolores and the Man in Black seem to be on a collision course, unless you buy into the popular fan theory, perhaps inspired by NBC's nonlinear family drama This is Us, that their storylines are actually happening many years apart. Meanwhile, Maeve seems to be figuring things out for herself without the same coaching Dolores gets. She remembers waking up accidentally and seeing the inner workings of Westworld, remembers being shot despite having no scar where the wound should be, and cuts herself open to find a bullet staffers had forgotten to remove. Piecing these details together, she starts getting herself killed deliberately in the hope of waking up in the shop again, and eventually gets her wish. Now, while Dolores continues to blunder toward her destiny, Maeve blackmails some Westworld staffers into explaining how she functions and upgrading her for purposes that remain to be seen. While all this is happening there's evidence of corporate espionage inside the park, and increasing evidence that Arnold hasn't had his last word yet on the future of Westworld and its hosts....

Much of what I could say about Westworld right now remains speculative, but for genre fans that's part of the fun of the show. The show is a kind of mystery or puzzle in which speculation is essential to the experience; if you're impatient for explanations it won't be for you. The game-like nature of the show extends to its soundtrack, which each week challenges you to identify the contemporary rock tune being covered on the player piano in Maeve's brothel. The show exists, as my mom used to say when we asked why too often, to make you ask questions. Who is the Man in Black? How did Arnold actually die, if he's actually dead? Who among the guests or staff might actually be hosts? Any show can beg questions like this, but Westworld's writing and acting make the questions worth asking and trying to answer. When Hopkins first appeared, I thought dismissively that he'd become the rich man's Malcolm McDowell, but he seems to be on his game here, while Harris makes an evilly enigmatic Man in Black. Wood and Newton are the real stars here, as well as our surrogates as seekers after the truth of Westworld, In their contrasting quests they seem more human than human, given the despicable nature of so many human guests in this decadent playground. But there are plenty of sympathetic humans as well -- presuming that they're human, of course. The mysteries of Westworld give the show an expansiveness beyond its massive budget. My worry is that once its mysteries are resolved it will lose a lot of its mystique. It may be better not to know enough than to know too much, but only time will tell one way or another. For now, it's my favorite new show of the fall.

Saturday, November 5, 2016

DOCTOR STRANGE (2016) in SPOILERVISION

Humor is clearly a key element in Marvel Studios' effort to make their movies "fun," as compared to Zack Snyder's relatively humorless Superman movies for Warner Bros. It's been widely reported that the Warner Bros. team is scrambling to inject more humor into their future projects in response to hostile reviews of the particularly humorless Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice, but to look at the latest Marvel Studios production, you'd think Marvel was just as desperate. The fact is, at least in my experience, that Doctor Strange has always been one of Marvel's more humorless comic book characters. For that reason, at least, Doctor Strange's glib comedy, from one-liners to pandering oldies-music references, seems to have been shoehorned into the story more blatantly than ever before. As a comic book fan (and something of an apologist for Dawn of Justice) I find myself resenting the need to inject comedy where I don't feel the need for it, for the sake of accessibility or to spare the layman the embarrassment of a film taking itself too seriously. By the same standard I should demand fight scenes and car chases in romance movies, lest they "take themselves too seriously," i.e. respect the integrity of their genre. But rather than rant further on that subject, let me say that the comedy bugged me this time more than usual because it seemed both more forced and more lame, whether it was the running gag of the villain calling the hero "Mr. Doctor" or Dr. Strange's Cloak of Levitation slapping him in the face. Let me suggest also that I found the forced humor annoying because Doctor Strange is actually a fairly decent film overall and would have remained so without the gags.

The strange thing about that is that Strange bears a strong structural resemblance to one of the genre's most notorious flops, Warner Bros.' Green Lantern (2011). Consider: asshole neophyte, already an expert in one trade, is plunged into a profoundly confounding and alien bootcamp-like experience, helped along by a sort of stuck-up mentor with a villainous destiny, before saving the world by defeating an almost inchoate cosmic entity. The difference is all in the execution, even if that comes with Marvel's formulaic comedy. The execution that counts here isn't so much the writing, since there's nothing particularly brilliant or original in the script or its realization, but the acting by the new champion in the Most Overqualified Cast of a Superhero movie Category. In the title role, Benedict Cumberbatch initially seems uncomfortable with both the jokey arrogance of his character and his American accent, but he grows on you and by the Crimson Bands of Cyttorak, he looks like the comics come to life. His supporting cast includes Chiwetel Ejiofor, Tilda Swinton, Rachel McAdams and Mads Mikkelsen, as compared to whoever was backing up Ryan (unDeadpool) Reynolds in Green Lantern. Hard to go wrong with that lineup, especially when your studio knows how to put together a superhero movie, as Warner Bros. arguably still hasn't fully learned in Christopher Nolan's absence.

Doctor Strange is a necessarily elaborated version of the original origin story by Stan Lee (here seen laughing over Aldous Huxley's Doors of Perception) and Steve Ditko. It's imperative for director Scott Derrickson and his co-writers to flesh out Stephen Strange's background by giving the star surgeon a girlfriend/colleague (McAdams) who doesn't exist in the original story and is, in fact, borrowed from other comics. In the original Strange's background is irrelevant after the setup of the smug surgeon losing effective use of his hands in a car wreck and falling from grace until he learns of a chance for mystic healing in the East. As is common and understandable in our time, the people Strange meets in the movie are different from those of the same names he meets in the comics. The Ancient One (Swinton) is a "Celtic" woman instead of an Asian man -- reminiscent of the High Lama of Shangri-La in Lost Horizon in that respect -- while her head disciple Mordo (Ejiofor) is white in the comics, black in the movie. Inevitably people have griped over Swinton stealing an Asian actor's rice bowl, so to speak, but unless you're going to protest Ejiofor's casting as well -- as some, less likely politically correct, surely have -- you should just shut up about Swinton. In the major departure from the early stories, Mordo is not the villain of the piece, though the movie sets him on the road to antagonism toward Strange, but rather the Ancient One's right-hand man in a battle with the renegade sorcerer Kacellius (Mikkelsen) and his little band of Zealots, who seek victory over death by bring Earth into the timeless Dark Dimension ruled by the dread Dormammu. In classic American hero tradition, Strange proves a quick study after a slow start, initially handicapped by ego and a reluctance to surrender to imponderable mystic forces, and finds a way to victory by breaking long-revered rules if not the "natural law" itself, despite the conservative resistance of Mordo and Wong (Benedict Wong) -- the latter upgraded from Strange's servant to the Ancient One's librarian and a sort of sorcerer in his own right.

Derrickson's film owes much of its look less to Steve Ditko than to Christopher Nolan; it has a dreamlike quality insofar as the mystical realm looks and moves a lot like Inception. To be fair, the sorcerers' space-bending antics wouldn't be out of place in a Ditko comic but as shown here they can't help but look derivative of if not stolen from Nolan. Fortunately, the Marvel team helps us keep our minds on the action, though the action here inevitably lacks some of the ideal clarity of the more conventional brawling in mundane superhero pictures. Oddly, Doctor Strange opts for anticlimax by hinging the picture on a mindgame the hero plays on Dormammu, well away from the main action on Earth but probably a necessity for fans who would have found no Doctor Strange film complete without the old hothead. The film seems to stop rather than end, without a really satisfying wrap-up or even a punchline, though of course the audience expects to see the real ending during and after the credits. In the end the charismatic cast puts the film over despite its flaws, and in a year of really bad superhero movies -- it's hard to decide whether the spasmodic Suicide Squad or the enervating X-Men: Apocalypse was the worst of all -- this one doesn't really seem bad at all.

Wednesday, November 2, 2016

Pre-Code Parade: HEADLINE SHOOTER (1933)

No one familiar with classic movies can watch Otto Brower's film and not think of Howard Hawks' His Girl Friday -- which is odd, because when you watch His Girl Friday you're supposed to think of The Front Page, the play and film Hawks famously adapted with a pioneering instance of gender-flipping. Watching Headline Shooter is like peeking into some alternate reality where Hawks and his writers looked at it first and said, "This story would work better if William Gargan were Frances Dee's boss." Dee is a hardboiled, often ruthless newspaper reporter who often works alongside Gargan's hardboiled, often more ruthless newsreel photographer. Gargan's Bill Allen is the sort of opportunist who makes his own opportunities. We first see him taking pictures of his girlfriend in bed eating crackers. The girl is a beauty pageant contestant. Bill goes to the pageant sponsor (Franklin Pangborn), who happens to own the cracker company, and convinces him to throw the contest to his girl, since he already has a perfect advertising photo of her. Meanwhile, he has instant newsreels of the pageant winner as a big scoop for his employer. Bill isn't the most exuberantly ruthless newsreel man in movies -- that would Clark Gable's character in Too Hot to Handle, from the era of Code Enforcement -- but he'll do for this picture. He meets his match in Jane Mallory (Dee), who matches him stride for stride as they cover an earthquake. This film is one of Merian C. Cooper's RKO productions so the special effects, combined with actual newsreel footage of the 1933 Long Beach earthquake, is top-notch for its time. The reporters invade a damaged hospital where doctors continue to perform an operation by candlelight while an outside wall collapses behind them. Later, Jane proves her journalistic moxie by stealing Bill's car to deliver her scoops.

So apart from a tough fast-talking girl reporter, what has all this to do with His Girl Friday? Well, it turns out that Jane has a boyfriend back down South, where she and Bill are headed to cover a major flood caused by a burst dam. The boyfriend, as film buffs must have guessed already, is poor Ralph Bellamy in total "Ralph Bellamy" mode. When did this happen to Bellamy? He's in a movie from the same year, Below the Sea, where he's a rough and tumble deep-sea diver and perfectly plausible as such. This is the earliest I've seen him in a "Ralph Bellamy" performance, as a hopeless stick in the mud who can never hold on to his girl. His best known work in this mode, of course, is in His Girl Friday, if only because the film is in the public domain as well as the canon of classic comedies. For a while here it looks like Bellamy will keep the girl, if only because Jane is repulsed by Bill's conduct during the flood. The reporters have learned that the dam was built with sub-par materials in a public ripoff with terrible consequences. A local judge asks them to suppress the story because the contractor was a relative of his and he'd be ruined politically even though he wasn't personally responsible. Bill appears to comply out of courtesy but passes off unexposed film as the damning footage, which promptly makes it into a national newsreel that promptly provokes the judge into killing himself. Jane is suddenly horrified by the news business and wants to go back home with Bellamy. But just as she submits her resignation her editor learns that a notorious gangster's moll is in the hospital. The regular beat reporter is unavailable and Jane knows that no one else but her has a chance of getting a newsworthy story out of the moll. When the gangster kidnaps Jane it's Bill, not Bellamy, to the rescue.

In an interesting early commentary on the manipulative power of the media, Bill extracts information from Ricci, a firebug fan of his (Jack La Rue with an Italian accent). Ricci has been eager to see some footage Bill took of him at a fireworks show. Bill suspects Ricci of having set a fire he filmed, in which his alcoholic buddy (Wallace Ford) was killed. Playing a hunch, he precociously blends the fireworks and fire footage together -- the filmmakers most likely filmed La Rue at the other location -- so that it looks like a guilty Ricci leaving the arson scene. In a guilty panic Ricci tells Bill where he can find the gangster who kidnapped Jane. In true hard-boiled manner, Jane is beating the gangsters at rummy when Bill charges in, setting up a final action scene running down fire escapes and into the street. There's no way your typical Ralph Bellamy and his down-home ways can compete with thrills like these. In Bill Jane gets a real man and keeps her career, announcing her marriage in an interview while a surprised Bill cranks his camera. The final clinch is cut short when fresh news breaks out and our heroes race off to their next adventure.

Headline Shooter lasts barely an hour yet seems overstuffed, if not padded. I've barely touched on the subplot with Wallace Ford's dipso cameraman, or on Robert Benchley's totally gratuitous, and not especially funny, cameo as a bumbling radio announcer covering the beauty pageant. But apart from the Benchley business the picture races along and is often spectacular in its disaster scenes. Shooter may get your attention for its resemblances to His Girl Friday, but it deserves some credit as a fine Pre-Code action comedy in its own right.

So apart from a tough fast-talking girl reporter, what has all this to do with His Girl Friday? Well, it turns out that Jane has a boyfriend back down South, where she and Bill are headed to cover a major flood caused by a burst dam. The boyfriend, as film buffs must have guessed already, is poor Ralph Bellamy in total "Ralph Bellamy" mode. When did this happen to Bellamy? He's in a movie from the same year, Below the Sea, where he's a rough and tumble deep-sea diver and perfectly plausible as such. This is the earliest I've seen him in a "Ralph Bellamy" performance, as a hopeless stick in the mud who can never hold on to his girl. His best known work in this mode, of course, is in His Girl Friday, if only because the film is in the public domain as well as the canon of classic comedies. For a while here it looks like Bellamy will keep the girl, if only because Jane is repulsed by Bill's conduct during the flood. The reporters have learned that the dam was built with sub-par materials in a public ripoff with terrible consequences. A local judge asks them to suppress the story because the contractor was a relative of his and he'd be ruined politically even though he wasn't personally responsible. Bill appears to comply out of courtesy but passes off unexposed film as the damning footage, which promptly makes it into a national newsreel that promptly provokes the judge into killing himself. Jane is suddenly horrified by the news business and wants to go back home with Bellamy. But just as she submits her resignation her editor learns that a notorious gangster's moll is in the hospital. The regular beat reporter is unavailable and Jane knows that no one else but her has a chance of getting a newsworthy story out of the moll. When the gangster kidnaps Jane it's Bill, not Bellamy, to the rescue.

In an interesting early commentary on the manipulative power of the media, Bill extracts information from Ricci, a firebug fan of his (Jack La Rue with an Italian accent). Ricci has been eager to see some footage Bill took of him at a fireworks show. Bill suspects Ricci of having set a fire he filmed, in which his alcoholic buddy (Wallace Ford) was killed. Playing a hunch, he precociously blends the fireworks and fire footage together -- the filmmakers most likely filmed La Rue at the other location -- so that it looks like a guilty Ricci leaving the arson scene. In a guilty panic Ricci tells Bill where he can find the gangster who kidnapped Jane. In true hard-boiled manner, Jane is beating the gangsters at rummy when Bill charges in, setting up a final action scene running down fire escapes and into the street. There's no way your typical Ralph Bellamy and his down-home ways can compete with thrills like these. In Bill Jane gets a real man and keeps her career, announcing her marriage in an interview while a surprised Bill cranks his camera. The final clinch is cut short when fresh news breaks out and our heroes race off to their next adventure.

Headline Shooter lasts barely an hour yet seems overstuffed, if not padded. I've barely touched on the subplot with Wallace Ford's dipso cameraman, or on Robert Benchley's totally gratuitous, and not especially funny, cameo as a bumbling radio announcer covering the beauty pageant. But apart from the Benchley business the picture races along and is often spectacular in its disaster scenes. Shooter may get your attention for its resemblances to His Girl Friday, but it deserves some credit as a fine Pre-Code action comedy in its own right.