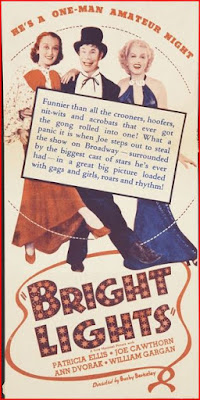

Busby Berkeley's comedy is a star vehicle for Joe E. Brown, Warner Bros.' leading comic of the pre-Code era, that makes a half-hearted try at being a newer kind of comedy. Acknowledging the rapid evolution within a year or so of what came to be called screwball comedy, Bright Lights grafts an already-standard feature of screwball, the "madcap heiress," onto the Brown project. Claire Whitmore (Patricia Ellis) apparently flits around the country doing whatever pricks her fancy, generating headlines whenever she's discovered. Reporter Dan Wheeler (William Gargan) discovers her working as a chorus girl in a burlesque theater where Joe Wilson (Brown) is the star comic. Wilson does an act with his wife Fay (Ann Dvorak) in which she sings while he, playing a drunk, heckles her from a balcony. Wilson combines insult humor and daredevil physical comedy; wandering the balcony to interact with audience members (or plants?), he constantly teeters on the railing until, challenged by the singer to show some talent of his own, he swings from a curtain rope Tarzan-style onto the stage, hitting the curtain and sliding down to join Fay in a soft-shoe routine. Berkeley makes the most of these scenes, shooting from angles that emphasize the (illusory) threat to the star while taking advantage of Brown's athleticism. The star does his own crucial stunt to climax the act, starting in close-up on the balcony and swinging into the curtain and sliding down. Berkeley then cuts to the stage to get a close shot of Brown landing and doing a forward roll, ending up on his feet and ready to dance. The director can trust his star later in the film to chase and then be chased by an airplane at an airport, and to hit the ground at the right moment for the plane to take off over his head. Brown gets to do the sort of things in his films, particularly those where he plays an athlete, that Buster Keaton should have been doing in sound films. Brown, however, was more of an all-around entertainer than Keaton, if less a creature of pure cinema, and Bright Lights highlights his versatility, showcasing not only his physical talent but other elements, like his drunk act and his baby talk storytelling, that probably haven't aged as well.

Brown himself is no screwball comic, though he's best remembered today for his comparatively screwball turn as an addled millionaire in Some Like It Hot. Apart from the madcap-heiress angle, Bright Lights could have been made years earlier. Tipped off by Wheeler, the producer of Anderson's Frolics hires the Wilsons and Whitmore for the latest edition of his Broadway show. Joe is ecstatic to hit the big time, but determined that Fay share the spotlight with him. When Anderson (Henry O'Neill) insists on pairing Joe with Whitmore for maximum publicity, Joe turns him down flat and is willing to sacrifice his chance at stardom, but Wheeler convinces Fay to nobly sacrifice her own ambitions so Joe can get his chance. She claims to be happy to live a life of luxury, complete with Arthur Treacher as the archetypal servant, but when the Wilsons' old burlesque producer needs an extra hand on the road, she jumps at the chance. Meanwhile, gullible Joe can't help falling for Whitmore, without realizing that she loves Wheeler. He finally sees the truth just after mailing a Dear Jane letter to Fay, prompting a final epic chase as Joe pursues the letter from mailbox to postoffice to airport to Akron, where Fay is performing. Inevitably, the film is far more star vehicle than screwball film, with the madcap heiress as little more than a plot complication, and while it's arguably more "Joe E. Brown, the Motion Picture" than his other vehicles, he's lively and likable enough to put it all over, with much help from Berkeley, who demonstrates here that he could direct a realistic backstage musical nearly as well as he managed his more famous flights of mass-choreographed fancy. Bright Lights catches Brown at or near the height of his popularity, but his star would dim by decade's end as the pretty faces of screwball eclipsed the grotesque nut comics of Brown's heyday.

A randomly comprehensive survey of extraordinary movie experiences from the art house to the grindhouse, featuring the good, the bad, the ugly, but not the boring or the banal.

Sunday, March 8, 2020

Tuesday, March 3, 2020

THE GIANT OF MARATHON (La battaglia di Maratona, 1959)

People may still know that the length of the modern marathon race is based on the distance from the Persian War battlefield of Marathon to ancient Athens, and that a messenger from the battlefield, having run the distance, dropped dead immediately after announcing the Athenian victory. If so, those same people may take Jacques Tourneur's peplum (assisted by Mario Bava) as the ultimate travesty, since the runner lives and gets the girl at the end of the picture. For the record, however, the legend of Phillipides dates back only to the second century of the Common Era, something like 500 years after the facts. Herodotus, the great historian of the war, mentions no such dying messenger. Tourneur, Bava et al really are no less entitled to exercise artistic license than the Roman writer Lucian was. Their writers thus make even more of Phillipides (Steve Reeves), who in their account is a peasant landowner whose past heroism against the Persians earns him leadership of the mythical Athenian Sacred Guard and a rallying point for supporters of the city-state's still-fledgling democracy. There remains an anti-democratic opposition that hopes for the restoration by Persia of exiled tyrant Hippias. Leading the opposition in the city is Theocritus (Sergio Fantoni), who schemes to co-opt Phillipides by marrying him off to the courtesan Charis (Daniela Rocca). Our hero already has his eye on blond, athletic Andromeda (Mylene Demongeot), the daughter of Theocritus' friend Creuso (Ivo Garrani). Phillipides can't be swerved from resistance, however, and Theocritus gradually alienates everyone before taking refuge with Hippias and the Persian army. Crucially, the bad guys fail to double-tap Charis after putting an arrow in her back when she tries to escape to warn the Athenians. She comes the nearest to performing the familiar Philippidean feat, while Philippides himself saves his energy for fighting. Marathon is noteworthy for having unusually good battle scenes for a peplum. I don't know whether Tourneur, Bava, or some second-unit person deserves the credit for this, but credit is definitely due given how feeble the genre's battle scenes often are. Strangely enough, Marathon climaxes with a sea battle, showing off a decent budget with full-scale ships and an underwater-attack sequence, along with a captive Andromeda sort of living up to her mythic namesake by being tied to the prow of a Persian ship. Steve Reeves's films apparently got bigger budgets in the wake of the global success of his Hercules films, and while he is what he is -- clean-shaven this time -- the money and a certain creative enthusiasm shows even in a faded pan-and-scan print on digital cable. It's hardly history, but it's fun on a matinee-movie level without being overblown in all the ways you'd expect from a more recent film.