The last time I tried to watch Michelangelo Antonioni's American debut was about twenty years ago, when I rented a VHS from the always-abundant Albany Public Library. My interest was prurient. I had heard that there was a large-scale orgy scene in the middle of the film. Watching the tape, I was impatient for the orgy to appear. It ended up disappointing me; it wasn't as pornographic as I'd hoped. The orgy done, I hit the stop button and rewound the tape.

The last time I tried to watch Michelangelo Antonioni's American debut was about twenty years ago, when I rented a VHS from the always-abundant Albany Public Library. My interest was prurient. I had heard that there was a large-scale orgy scene in the middle of the film. Watching the tape, I was impatient for the orgy to appear. It ended up disappointing me; it wasn't as pornographic as I'd hoped. The orgy done, I hit the stop button and rewound the tape.Zabriskie Point was also known to me for being a great flop when it came out, another manifestation of Hollywood's desperation over reaching the new youth audience. The beginning of the Seventies was a time when the studios seemed ready to throw money at anyone from Antonioni to Russ Meyer, and the money often ended up going right out the window. My younger self had heard of Antonioni, and had even tried to watch L'Avventura some time earlier, without really appreciating it, though I had better luck with Blow-Up. Since then, and quite more recently, I was lucky enough to see The Passenger on a big screen. So when I heard that Zabriskie was coming out on DVD, I decided to give it another chance, as a real movie this time, and the Library dependably acquired the disc this month.

The one detail I remembered well apart from the orgy was the opening student radical rap session. I'm something of an historian, so this bit interested me even back then. I think people make a mistake when they look for something substantive or meaningful in plot terms in all the talk. It's really meant, I think, to create an atmosphere, a feeling for the moment in history. This seems to be Antonioni's approach throughout. Zabriskie Point is an immersion in the sights and sounds of American circa 1970, and this type of protest conclave was part of the collective mindscape. There are moments of amusement for the attentive (Black radical: "White radicalism is a mixture of bullshit and jive.") but it's not meant to inform or enlighten you. Agitprop it ain't. What ends up being relevant is our protagonist Mark's dissatisfaction with all the deliberation. "I'm willing to die, too," he tells the group, "[but] not of boredom." A friend explains that "Meetings aren't his trip," but another radical remarks: "That bourgeois--bourgeoisie individualism that he's endorsing is gonna get him killed." Because of what follows, we might be tempted to take this as the story's moral in advance, but I don't think Antonioni and his team of writers are really that interested in morals or politics. When someone closes the scene by saying, "denounce bourgeois individualism," it's more of a punch line than an editorial statement.

Mark is simply impatient. "The chick at the meeting said people only move when they need to," he tells his pal, "Well, I need to sooner than that." He stocks up on guns, making things easier for himself by telling the gun-store owner that he lives in a "borderline" neighborhood and "we just have to protect our women." Peaceful demonstrations just get his friends put in jail, and he ends up doing a little time himself when he tries to bail his pal out. A dumb cop asks for his name. He gives, "Karl Marx." "How do you spell it?" the cop asks.

Looking for action, he finds the cops about to storm a campus Liberal Arts building occupied by black radicals. When the pigs blow away one of the men, thinking he was going to pull a gun on them, Mark decides to pull his gun on the pigs. But before he can draw or fire his weapon, he hears a shot and sees a cop go down. "I wanted to, but someone else was there," he later explains. Assuming that he'll be a suspect, he steals an airplane with ridiculous ease and flies it into the desert. On his way, he playfully buzzes a car driven by Daria, who's driving through en route to her boss's lair in Arizona. This is meeting cute on a gigantic scale, and Antonioni doesn't fake a thing. That's Mark Frechette in the plane, and there aren't any soundstage pick-up shots in this near-parody of North by Northwest.

Daria is an alienated young woman who works for a vaguely alienated, vaguely unscrupulous boss played with vague authenticity by Rod Taylor. Earlier in her trek, she was menaced by a pack of feral kids who play amid overturned cars and broken pianos and say such cute things as, "Can we have a piece of ass?" After that, being harassed by an airplane might have seemed somewhat less menacing. After Mark lands, they make friends and then make love after some typical hippie babble. Daria smokes, but Mark doesn't. "This group I was in had rules about smoking," he relates, They were on some reality trip." "What a drag," Daria commiserates.

Daria Halprin has a healthy appetite for life in Zabriskie Point. Spin that dress, girl!

She suggests that "It'd be nice if they could plant thoughts in our heads, so nobody would have bad memories." Mark is before long planting something else in her, but this seems to plant thoughts as well. This is the famous orgy in the desert, which is really Daria's erotic delusion of polymorphous perversity (is she imagining she and Mark multiplying their own bodies?) and universal love covering the world in twos, threes and fours.

Mark approaches things more prosaically.

Mark: I always knew it would be like this.

Daria: Huh?

Mark: The desert.

Despite knowing himself innocent, Mark seems to be having final thoughts. After nearly killing a cop who passes through, he dumps his ammo on the sand and decides to return the plane he "borrowed" after applying a semi-psychedelic, semi-sophomoric paint job to it. Quite abruptly we're left without our hero, or this film's equivalent of one, with twenty minutes to go.

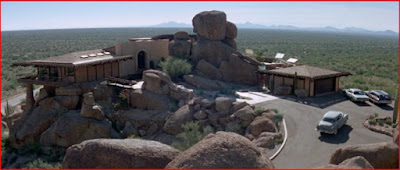

So Daria carries on with her trip and arrives at Taylor's lair. And I do mean lair. This little palace seemingly carved out of a mountain looks worthy of a small-time Bond villain, and ends up rather the same way, at least in Daria's mind.

The movie's infamous finale is a bookend to the orgy. Having learned via car radio of Mark's fate, Daria's romantic idealism is destroyed, and like Mark and many others of his generation, she succumbs to fantasies of absolute destruction.

Two things about Zabriskie Point seemed to trip up initial audiences. First, there was an assumption that Antonioni was making some sort of personal political statement and that it wasn't flattering to the United States. People reacted as if he endorsed the opinions expressed in the rap session or advocated the detonation of refrigerators and bookshelves Daria fantasizes about. They harped on his constant attention to billboards, logos and other advertising art as if they assumed he was condemning it all. If that's so, then mine is a perverse appreciation of the film, since those details make it a realistic reproduction of the world of my childhood. I don't think that this foreigner's attention to superficial details means that he's condemning some perceived American superficiality. Rather, it's just the easiest way to define America in cinematic terms, and no different in that respect than his soundtrack, which ranges from Pink Floyd and Jerry Garcia originals to "The Tennessee Waltz" in one old cowboy's moment of serenity over beer in a bar and Roy Orbison singing, "Zabriskie Point is anywhere" over the end credits. One can go overboard with a thesis contrasting the ad-ridden city with the purity of the desert because...well, it's a desert! A fine place to have a be-fruitful-and-multiply fantasy, don't you think? As a matter of fact, yes it is, because Antonioni likes deserts, and one suspects that the location was kind of an end in itself for him.

One man's scathing critique of consumerism (above) is another's blatant product placement. If Antonioni had real critical intent behind his commercial imagery, it'd probably be lost on many modern viewers; some might even call him a sell-out.

The other detail that riled people was the self-evident amateurness of neophyte stars Mark Frechette (soon to be a real-life criminal) and Daria Halprin (soon to be Mrs. Dennis Hopper). But dare I suggest that they're supposed to be shallow, and that we aren't meant to see them as brilliant, lovable individuals who undergo intersecting character arcs and complete each other? Let's face it, anyway: lots of us know people in real life who are pretty much ciphers like these. Once you understand that Zabriskie Point is a broad-stroke sketch of the U.S. with a Euro sensibility indifferent to concerns for closure or other narrative niceties, and mainly a pretext for Antonioni to let rip with masterful self-indulgence, the sooner you'll lower your expectations of the actors and accept them for the types they are. There's a certain sensibility that needs to care for characters and will never appreciate films like Zabriskie, but movies are about more than characters and can sometimes thrive even without careful attention to them in the novelistic manner. Some people will never accept that, but I hope they might at least stop confusing their preferences for aesthetic laws.

Dean Tavoularis did wonders as Antonioni's production designer. You have to see this bit in motion with the waving flag and the rotating clocks on Taylor's TV screen to get the full effect.

That VHS from twenty years ago was not letterboxed. That made a world of difference, because the widescreen DVD reveals Antonioni's vision in its proper proportions. Whether he's taking in the sprawl of the desert or filming Rod Taylor in his office, nearly every image in the film (some seem to be stock or news footage of student protests) is a marvel of composition. Antonioni is the Michelangelo of widescreen (for who else could be?) and Zabriskie Point is art run amok. I hope the snips have made that clear. It took a while, but I learned how to appreciate this film. I commend it to the faster learners in the wild world of cinema.

The trailer (uploaded from TCM by foxter65)offers a fair sample of airplane antics, billboards and orgy action. Check it out.

Being a Pink Floyd fan I've always wanted to see this, but was never able to get my hands on it. I wasn't even aware that it was available. I'll have to search it out.

ReplyDeleteIt only just came down the chute, for us in the US at least. Wikipedia reports that some material from Dark Side of the Moon started as rejects from Zabriskie Point. Antonioni apparently wanted Sid-style stuff from them.

ReplyDelete