The early reviews on Toy Story 3 make it look like Pixar has done it again. I intend to verify that for myself later on this weekend, and I'll be curious to see how the film ranks not only among Pixar's impressive achievements but in that category of films that are third in a series. The third episode is where even the mightiest moviemakers can reach beyond their grasp, The Godfather Part 3 being the saddest example of the risks involved. But sometimes it's only on the third time around that a series really hits its stride, even if it ends there, too. The third episode of a trilogy, after all, probably ought to be the best, but sometimes it's the third film that assures a series of many more installments, or at least gives it a promise of fresh life.

The early reviews on Toy Story 3 make it look like Pixar has done it again. I intend to verify that for myself later on this weekend, and I'll be curious to see how the film ranks not only among Pixar's impressive achievements but in that category of films that are third in a series. The third episode is where even the mightiest moviemakers can reach beyond their grasp, The Godfather Part 3 being the saddest example of the risks involved. But sometimes it's only on the third time around that a series really hits its stride, even if it ends there, too. The third episode of a trilogy, after all, probably ought to be the best, but sometimes it's the third film that assures a series of many more installments, or at least gives it a promise of fresh life.The following is a tentative list of my favorite "threequels," taken from an inevitably incomplete sample. I'm sure that older viewers could cite third episodes from some of the great B-movie series of the 1930s and 1940s, for instance, though you will see one film from that period here. For my purposes, a series is a set of films that form a conscious narrative sequence or follow a consistent character through continuing if often unlinked adventures. One film on my list is arguably an exception to this rule that might bring other exceptions to mind. For the historical record, this list is as of June 17, 2010. Later, after I see Toy Story 3, I'll let you know whether it earned a place on the list.

10. King Kong vs Godzilla (1962). The third Godzilla film and the first in seven years, this dream match with the world's other favorite giant monster is a pop riot that I've never outgrown. In the American dubbed version it's a kind of idiot masterpiece, building on Ishiro Honda's own obviously intentional comedy. I love the two stooges of the Pacific Pharmaceutical Company playing Great Yellow Hunters on Faro (? - were they looking for a giant monster or Ingmar Bergman?) Island, Toho's colorful riff on Skull Island and the "Pow goes Kong?" buffoonery of their boss, not to mention our mangy hero's berry-juice addiction. Sure, the effects and especially poor Kong's suitmation have their limits, yet I wouldn't change a thing about this wonderful spectacle.

9. Army of Darkness (1993). Sam Raimi's third adventure for Bruce Campbell's Ash illustrates the threequel tendency to take a series in a wild new direction, this one largely inspired by A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court. While it's no improvement on Evil Dead 2, it's a very welcome encore for arguably the greatest physical comedy character in modern American film, and the last real expression of Raimi's original cranky sensibility before he aimed and more or less achieved respectability, albeit at a price.

8. Billion Dollar Brain (1967). The third Michael Caine vehicle based on Len Deighton's Harry Palmer series of novels was entrusted to Ken Russell, who was probably just the director to do justice to its mad story of an American multi-millionaire (Ed Begley) forming a private army to invade the Soviet Union. Inevitably played less straight than its predecessors, this is worth seeing for its parody of anti-communist mania and Russell's audacious realization of Begley's insane vision as a modern replay of Aleksandr Nevskii's battle on the ice.

7. Battles Without Honor and Humanity: Proxy War (1974). Take my word on this one. It's the middle film of Kinji Fukasaku's five-part epic of yakuza war and intrigue in postwar Hiroshima, Japan's counterpart to the Godfather films. This is really just another excuse to recommend that people see all five films to learn why Fukasaku is one of my favorite directors and Bunta Sugawara one of my favorite crime-cinema actors. Consciously dedicated to deromanticizing the yakuza and their alleged codes of honor, this series attains a kind of cynical grandeur in its own right.

6. Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004). Here's what I mean by fresh life. This series already felt tired by the time Chris Columbus was done with the second film -- maybe because Richard Harris was dying before our eyes -- but the third episode brought us the theoretically incongruous Alfonso Cuaron, who gave us a richer, more moody story that signaled the series's maturation in sync with the ripening of its young stars. It also set the stage for Cuaron's personal triumph of the decade, Children of Men.

5. Escape From the Planet of the Apes (1971). The previous installment ended with the end of the world, leaving the producers no choice but to strike out in some unanticipated new direction. The inspired answer to the challenge was to reverse the course of the original film and send Cornelius and Zira (plus the hapless Sal Mineo) to our world. Unafraid to be goofy or campy, the third Apes film also set the stage for the films that came after and before it before reaching its inevitable grim conclusion. The Apes movies set the standard for a sci-fi series before Star Wars came along, and this episode deserves credit for expanding the scope of the series beyond its original dystopian satire.

4. Son of Frankenstein (1939). This film's existence is one of the first triumphs of genre movie fandom. Universal had buried its signature horror genre three years earlier but was stunned to see a revival double-bill of Frankenstein and Dracula become a sleeper hit in 1938. The studio brought Boris Karloff back for an encore, albeit dumbed down (to the actor's apparent relief) from the pidgin-eloquent soul of Bride of Frankenstein. Karloff was still able to invest the Monster with emotion, though the show was nearly stolen from him by his new sidekick Ygor (Bela Lugosi), not to mention his manic new mentor (Basil Rathbone). Rowland V. Lee juggled this thing practically to the finish line, but it has a panache all its own that places it with its two mighty predecessors rather than with the B films that followed.

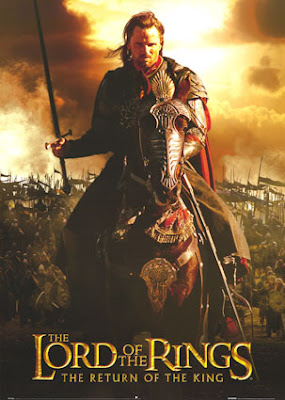

3. The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003). It seems too long at times, but it could also have been longer (or, had Peter Jackson been thinking straight, "The Scouring of the Shire" could have been his fourth movie in its own right), and it has some of the greatest battle scenes ever. The series as a whole is a great ensemble piece, and in this third and final installment we still have new faces coming to the fore, particularly John Noble as the mad king Denethor. This is a third film that was consciously designed as a finale, so it could be loaded with big moments (and perhaps too many final bows), most of which work as planned. We're probably lucky it was made in those good old days when three three-hour films in three years was not seen as a waste of potential box office. Were Jackson put to work now, based on what he hopes to do with The Hobbit, we might be talking about the sixth film of the series here, or else I'd have to write about The Two Towers, Part One.

2. Goldfinger (1964). Guy Hamilton's film is the best example of a series hitting its stride in the third installment. More than the two previous film, Goldfinger set the tone for James Bond films to follow. It had the big song. It had the iconic antagonists, Oddjob especially. At Fort Knox it had the big set-piece battle. It unfolded a little before my time, but my impression is that this is where a promising series became a pop phenomenon. Its exuberance, fueled by John Barry's bombastic score, is still palpable today.

1. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966). Here's the exception I mentioned earlier. We talk of Sergio Leone's "Dollars trilogy," and about Clint Eastwood's "Man With No Name," but the latter was really a construct of the United Artists publicity department, as far as I can tell, and people can still debate whether Eastwood was playing the same guy in all three films. The fact is, of course, that Eastwood is the same guy himself, imposing a visual equivalence on the films that Leone enhances by dressing him similarly throughout. Gian Maria Volonte appears in the two earlier films as two different characters, and Lee Van Cleef appears in the two latter films as two different characters, so it isn't automatic that Eastwood is always the same character. But the three films seem to me a thematic and aesthetic series, unified by Eastwood as a motif if not a character, while the Eastwood-less Once Upon a Time in the West does not seem like a continuation of the original trilogy. Leone's third western is a series film in the same way Road to Morocco is; the names change but an essence persists. As long as we accept it as the third in a series, it's easily the best film that I can think of right now in that position. If you want to be more strict about it, Goldfinger is definitely an honorable alternative. The way some people are talking about Toy Story 3, I may have to reconsider the top of the list, but you'll find out whether I do or not soon enough....

I would have to put Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade on a list like this... even though Raiders is better, I am probably more likely to reach for Last Crusade if putting one of them on. And even with its serious problems, I would also likely include The Godfather III.

ReplyDeleteGood calls on every film you've included. I'd probably have tried to find space for 'The Bourne Ultimatum' (parts two and three, with Paul Greengrass at the helm, are the real high gear of the franchise after the wobbly start of Doug Liman's first instalment).

ReplyDeleteAlso 'Day of the Dawn', while not as iconic and satirically-edged as 'Dawn', represents a natural progression in Romero's zombie sequence.

Interesting post here Samuel. THE RETURN OF THE KING is the greatest "third" film of all time for me, but I dare say TOY STORY 3 makes a strong run at that designation, as (yes) it is yet another glorious Pixar triumph, that fully deserves the unanimous reviews it has garnered (it's the most emotional film of the three. SON OF FRANKENSTEIN (still behind the original and BRIDE) is a great choice too.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the comments, everyone.

ReplyDeleteDave: Many people love Last Crusade and find it an enhancement of the Jones saga, but I found its adventure plot repetitive and the father-son comedy doesn't quite compensate. I like it better than Godfather III, which fails for me on the implausibility of Michael's desire for redemption. You might say that Puzo and Coppola know the character better than I do, but the third film makes me wonder.

Neil: I knew someone would point out something I liked but forgot, and Day of the Dead is just such an item. I'd probably place that at No. 11 (now No.12) on this list. I've seen no Bourne films due to a lingering prejudice against Robert Ludlum but I like the Greenglass films I have seen. I'll have to break down and look at them all sometimes.

Sam J: Now that I've reviewed Toy Story 3 you'll see that I place it just behind Return of the King in a revised list. My top two stay where they are because they are continuations of concepts or themes already established but also singularly and self-sufficiently iconic in their own rights.