You can see the first hints of the road-trip comedy in Mervyn LeRoy's film, which offers Joe E. Brown as a dubious chaperone to a wastrel friend on a cross-country trip to California. But most of the action takes place at the end of the trip, and overall Warner Bros. hasn't yet figured out how to best exploit Brown's slapstick athleticism; here he's pretty much a guy with a big mouth, a figure whose clowning borders on the pathological. He's the guy who shows up at the young people's "baby party" and takes the act to extremes, arriving in a pram and really, really getting into the role more than anyone else. The story is conventional stuff, having both Brown and his sidekick (William "Buster" Collier) fall for California girls but having their romances complicated by the arrival of an old flame from the east, for Collier, and the reappearance, for Brown, of an enemy made on the road. This enemy gives Broadminded its main interest today, for he is Bela Lugosi, six months after the release of Dracula.

For Lugosi this movie represents a road ultimately not taken. It's an attempt by Warners to try him out as an all-purpose ethnic, in the role of a tourist from the country of "South America." That role requires Lugosi to be very different from Dracula. He must be loud, he must talk relatively fast, and when Brown really annoys him, as when the comic sprays ink on Bela's dessert, the offended man gives chase at a vigorous, elbow-churning pace. It's not really a great performance, but it belies any notion that Lugosi's Dracula represents the limits of his English or his acting style. He's not exactly convincing as a Latin American, especially by today's standards, but if you pay attention you can hear how he's modulating his accent slightly to fit the part. But if Broadminded gives us a rare glimpse of a non-typecast Lugosi, LeRoy clearly appreciates Bela's essential gifts. The most Lugosian moment in the film comes when Brown's party are dining in a restaurant booth and Brown recounts his dealings with his Latin antagonist, not realizing that the man himself has just been seated in the next booth. Lugosi hears Brown's boasting and, recognizing the hated voice, gets up and peers over the partition behind him at Brown. Naturally, this is the last place Brown expected to see Lugosi, and his reaction to seeing Bela's face is an easy gag. But then LeRoy holds a shot of Lugosi peering over the partition, now with only half his face showing, most importantly those eyes. If more directors found ways to exploit Lugosi's most obvious gifts without relegating him to what was quickly becoming a ghetto for horror films, we might think of Broadminded as a different kind of milestone in a very different career.

A randomly comprehensive survey of extraordinary movie experiences from the art house to the grindhouse, featuring the good, the bad, the ugly, but not the boring or the banal.

Sunday, July 31, 2016

Friday, July 29, 2016

DVR Diary: THE SILENT STRANGER (1968-75)

If spaghetti westerns owed their global popularity to Sergio Leone imitating Akira Kurosawa, it probably was inevitable that the archetypal circle would close with a spaghetti cowboy visiting the land of samurai. This was accomplished by Tony Anthony, an American who started more obscurely than Clint Eastwood and scored a hit with A Stranger in Town, a film he co-produced with M-G-M money. "The Stranger" became Anthony's spaghetti persona, with the exception of his title character in Blindman, where he was upstaged by Ringo Starr. The Silent Stranger was the third Stranger movie made, but despite the character's apparent popularity it sat shelved for seven years, not appearing until near the tail end of the spaghetti era, and after other east-meets-westerns (Red Sun, The Fighting Fists of Shanghai Joe, etc.) had come and gone. Silent Stranger remained a novelty as a west-meets-eastern, and it's really more interesting as a samurai movie than as a transplanted spaghetti.

Why the film is called The Silent Stranger is beyond me, since Anthony offers a sporadic voice-over commentary on the action. The story opens in the Klondike, where The Stranger rescues a Japanese man from some ruthless northwestern types. The rescue comes just a little too late, since the Japanese man dies, but he's rescued enough to give Stranger a scroll, with instructions to deliver it to Osaka in return for $20,000. Crossing the Pacific, Stranger becomes the typical Ugly American visitor, expecting to be understood when he speaks pidgin English and drops names. Gradually a Red Harvest type situation emerges as two factions of samurai fight for control of a territory and Stranger, possessing the scroll everyone covets, ends up in the middle. Since this is a spaghetti samurai film, a machine gun factors in the conflict. The scenes showing the oppression of the common people are the best in the picture, particularly a sequence in which tax collectors compel peasants to come out of their houses one family at a time to pay up and rough up those who won't or can't pay, with one man nervously waiting for his turn while Stranger holds him captive. These moments of frantic cruelty feel authentically Japanese, at least in a generic sense, making me wonder whether there was an uncredited native second-unit man during the location shoot. Another highlight is a fight highlighting clashing national styles, as an unarmed Stranger tries to bludgeon a samurai with a hunk of bamboo, only to have the swordsman gradually whittle his weapon down to a nub. At its best, Silent Stranger benefits from an engaging grotesquerie that encompasses the smugly oafish Anthony himself and extends to a villain's dwarf sidekick. At its worst, it takes for granted what it should not, that Tony Anthony is a funny guy, or that anything can be made funny by playing a flute. Inevitably the film is an ego trip for Anthony, and that trips it up, since by a certain point The Stranger is the least interesting thing about the film. It's still an interesting and often entertaining picture, but I recommend it in spite of its star.

Why the film is called The Silent Stranger is beyond me, since Anthony offers a sporadic voice-over commentary on the action. The story opens in the Klondike, where The Stranger rescues a Japanese man from some ruthless northwestern types. The rescue comes just a little too late, since the Japanese man dies, but he's rescued enough to give Stranger a scroll, with instructions to deliver it to Osaka in return for $20,000. Crossing the Pacific, Stranger becomes the typical Ugly American visitor, expecting to be understood when he speaks pidgin English and drops names. Gradually a Red Harvest type situation emerges as two factions of samurai fight for control of a territory and Stranger, possessing the scroll everyone covets, ends up in the middle. Since this is a spaghetti samurai film, a machine gun factors in the conflict. The scenes showing the oppression of the common people are the best in the picture, particularly a sequence in which tax collectors compel peasants to come out of their houses one family at a time to pay up and rough up those who won't or can't pay, with one man nervously waiting for his turn while Stranger holds him captive. These moments of frantic cruelty feel authentically Japanese, at least in a generic sense, making me wonder whether there was an uncredited native second-unit man during the location shoot. Another highlight is a fight highlighting clashing national styles, as an unarmed Stranger tries to bludgeon a samurai with a hunk of bamboo, only to have the swordsman gradually whittle his weapon down to a nub. At its best, Silent Stranger benefits from an engaging grotesquerie that encompasses the smugly oafish Anthony himself and extends to a villain's dwarf sidekick. At its worst, it takes for granted what it should not, that Tony Anthony is a funny guy, or that anything can be made funny by playing a flute. Inevitably the film is an ego trip for Anthony, and that trips it up, since by a certain point The Stranger is the least interesting thing about the film. It's still an interesting and often entertaining picture, but I recommend it in spite of its star.

Tuesday, July 26, 2016

Serial Pulp: THE SPIDER'S WEB (1938), Chapter Five: Shoot to Kill

Nearly all our heroes were in peril at the end of the previous chapter. The Spider himself was trapped in a room with a gas bomb and killing steam, while Nita, Jackson and Ram Singh were shackled inside the archetypal flooding room. The first cliffhanger is hurdled easily as The Spider simply forces his way out a window. Meanwhile, The Octopus taunts the others via intercom, while Ram Singh vows to carve his name in the villain's heart. The Spider goes back into the trap house and takes out the goons operating the radio and speakers. He somehow figures out that his friends are in danger and pries open the airtight door to the flood room, clobbering two foes with the rush of water while he discreetly hops on top of a chair. After he frees his friends, Ram Singh notices that the two gangsters are coming to. Something violent is cut from the picture here, at least in the version I saw, for we now see The Spider and Ram Singh approaching the camera, and then we see the gangsters' bodies twitch and go limp.

The Octopus is royally pissed at his men's latest failure to kill Richard Wentworth and his friends. ??, as the actor playing The Octopus is known for now, knows how to work his full-face mask to make it express his rage. He puts his long-term plans to dominate American utilities on hold for the moment to make destroying The Spider priority number one.

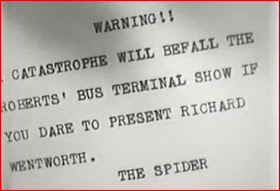

Learning through his underworld sources (i.e. Blinky McQuade's) that everyone's out to get The Spider, Wentworth switches up. His plan is to make a public spectacle of himself at a charity magic show in order to draw out The Octopus's men, if not The Octopus himself. He seems awfully confident that the bad guys will attempt some surgical strike on himself instead of bombing the bus station (i.e. the set from the chapter-one cliffhanger) where the charity show will take place. The Octopus takes the bait but complicates things a little by issuing a threat to Wentworth in The Spider's name.

The Octopus's idea is that the bogus threat will draw the actual Spider to the scene, where he can then eliminate both his enemies at once. He still doesn't realize how easy that would be, but I'm not sure of the soundness of his plan. Why wouldn't The Spider, presuming he was someone other than Wentworth -- as The Octopus must presume so far -- simply stay away on the assumption that the charity show will now be heavily guarded? For the plan to work, this theoretical Spider must assume that someone, presumably an enemy of his, actually will go after Wentworth. Of course, this criticism is moot because The Spider can't help but be there is Wentworth is. The funny part is that no one -- the press, the police and, of course, Wentworth, takes the fake threat seriously. Sending threats to the newspapers isn't The Spider's M.O., and as Wentworth asks, what would The Spider have against him. Wentworth's a crime fighter in his own right, after all, while The Spider, in Wentworth's words, is "a perfectly nice sort of fellow ... who goes around punishing people the law doesn't have time to catch up with." Wentworth's chat with Commissioner Kirk allows the latter to air anew his suspicions about Wentworth being The Spider, since Ram Singh had left his turban, lost when the bad guys clobbered him in the previous chapter, in the trap house which the cops found littered with corpses marked with The Spider's brand. Ram Singh, after all, is the only man in the entire city who wears a turban, isn't he?

In any event, it's on with the show despite the dubious threat. Wentworth arranges to have the more suspicious spectators herded to one section of the makeshift theater, but The Octopus's chief goon (Marc Lawrence) recognizes the set-up and orders a cohort to head over to where a spotlight has been set up. The gangster sneaks up there and kayoes the lighting man, all unbeknownst to the security detail. They're the same people who let Lawrence into the bus station with a loaded gun, despite the publicized (albeit mocked) threat to Wentworth's life. Nita takes the stage in costume to introduce Wentworth, who immediately draws fire from Lawrence. Wentworth seems unhurt, almost as if the bullets hit a force-field. Why didn't they just blow the place up? That's what a real Norvell Page villain would do. Now The Spider appears, faster than the quickest change would make possible, to open fire on the gangsters. But now the wisdom of Lawrence's tactics becomes apparent, because The Spider has maneuvered himself into the perfect position for that goon up above to drop that spotlight on him. Thus ends a relatively uneventful chapter dominated by The Spider and Octopus trying to outwit each other. You still get the sense that The Octopus is somewhat more dangerous than the typical serial villain, but he clearly wasn't at his best this time. Let's wish him better luck next time, since The Spider's Web isn't even halfway done yet.

The Octopus is royally pissed at his men's latest failure to kill Richard Wentworth and his friends. ??, as the actor playing The Octopus is known for now, knows how to work his full-face mask to make it express his rage. He puts his long-term plans to dominate American utilities on hold for the moment to make destroying The Spider priority number one.

Learning through his underworld sources (i.e. Blinky McQuade's) that everyone's out to get The Spider, Wentworth switches up. His plan is to make a public spectacle of himself at a charity magic show in order to draw out The Octopus's men, if not The Octopus himself. He seems awfully confident that the bad guys will attempt some surgical strike on himself instead of bombing the bus station (i.e. the set from the chapter-one cliffhanger) where the charity show will take place. The Octopus takes the bait but complicates things a little by issuing a threat to Wentworth in The Spider's name.

The Octopus's idea is that the bogus threat will draw the actual Spider to the scene, where he can then eliminate both his enemies at once. He still doesn't realize how easy that would be, but I'm not sure of the soundness of his plan. Why wouldn't The Spider, presuming he was someone other than Wentworth -- as The Octopus must presume so far -- simply stay away on the assumption that the charity show will now be heavily guarded? For the plan to work, this theoretical Spider must assume that someone, presumably an enemy of his, actually will go after Wentworth. Of course, this criticism is moot because The Spider can't help but be there is Wentworth is. The funny part is that no one -- the press, the police and, of course, Wentworth, takes the fake threat seriously. Sending threats to the newspapers isn't The Spider's M.O., and as Wentworth asks, what would The Spider have against him. Wentworth's a crime fighter in his own right, after all, while The Spider, in Wentworth's words, is "a perfectly nice sort of fellow ... who goes around punishing people the law doesn't have time to catch up with." Wentworth's chat with Commissioner Kirk allows the latter to air anew his suspicions about Wentworth being The Spider, since Ram Singh had left his turban, lost when the bad guys clobbered him in the previous chapter, in the trap house which the cops found littered with corpses marked with The Spider's brand. Ram Singh, after all, is the only man in the entire city who wears a turban, isn't he?

Does this make Nita Van Sloan a costumed crimefighter in her own right?

In any event, it's on with the show despite the dubious threat. Wentworth arranges to have the more suspicious spectators herded to one section of the makeshift theater, but The Octopus's chief goon (Marc Lawrence) recognizes the set-up and orders a cohort to head over to where a spotlight has been set up. The gangster sneaks up there and kayoes the lighting man, all unbeknownst to the security detail. They're the same people who let Lawrence into the bus station with a loaded gun, despite the publicized (albeit mocked) threat to Wentworth's life. Nita takes the stage in costume to introduce Wentworth, who immediately draws fire from Lawrence. Wentworth seems unhurt, almost as if the bullets hit a force-field. Why didn't they just blow the place up? That's what a real Norvell Page villain would do. Now The Spider appears, faster than the quickest change would make possible, to open fire on the gangsters. But now the wisdom of Lawrence's tactics becomes apparent, because The Spider has maneuvered himself into the perfect position for that goon up above to drop that spotlight on him. Thus ends a relatively uneventful chapter dominated by The Spider and Octopus trying to outwit each other. You still get the sense that The Octopus is somewhat more dangerous than the typical serial villain, but he clearly wasn't at his best this time. Let's wish him better luck next time, since The Spider's Web isn't even halfway done yet.

Sunday, July 24, 2016

Pre-Code Parade: UNTAMED (1929)

Joan Crawford's first talking feature, directed by Jack Conway, doesn't live up to its title, and it definitely doesn't live up to its cable-guide synopsis, which led me to expect Crawford as something closer to a female Tarzan. She's no jungle girl, alas, but from the perspective of Hollywood South America may as well have been Darkest Africa, and that's where we find "Bingo," the daughter of a down-on-his-luck oil prospector raised among the common people, whom she entertains with the untamed sounds of Arthur Freed and Nacio Herb Brown's The Chant of the Jungle. Jungle music it isn't, just as The Pagan Love Song wasn't very pagan. I suppose Bingo (nee Alice) is untamed insofar as she's been raised on the streets and has a certain rough manner. When some slob tries to grope her during a dance she yells out, "Somebody give me a knife!" The same slob later kills her dad, just as his old pal Murchison (Ernest Torrence) was going to tell him that one of his mines has finally paid off, making him (but now Bingo) a millionaire.

You can see where this is going, and the idea of the looming, lunkish Torrence, who made his name as a psycho hillbilly in Tol'able David and was rendered still more exotic by sound's exposure of his Scots burr -- acting as Bingo's Henry Higgins to make her fit for society has some potential. Unfortunately, Untamed doesn't go there. Instead, her social education is presented as a fait accompli so the picture can take up a new subject. On the boat back to America Bingo had met cute with Andy McAllister (Robert Montgomery), who unfortunately already has a date for the voyage. That doesn't stop Bingo, who after bopping her rival on the nose on the ship hooks up with Andy again in New York, where practically the last untamed thing Bingo does is goad Andy and a rival suitor into a boxing match in the middle of a swanky party at her mansion. From this point, Untamed really becomes Andy's story, driven by a male-pride melodrama. The young man has been bred for society but has no immediate prospects. This means that, should he marry Bingo, he won't be able to give her the lifestyle to which she has but recently become accustomed. For Bingo this isn't a problem, as she doesn't see why they couldn't live off her money, as managed by Murchison. This is where male pride comes in; it would be shameful for Andy to live off his wife, especially when Murchison suspects him of being a gigolo -- even though the straitlaced old man can't bring himself to utter the word. Recognizing that psychology at work in Andy, Murchison tries to manipulate him out of Bingo's life by appearing to consent to a wedding while offering Andy a "wedding gift" of $30,000. He sweet-talks Andy, assuring him that it won't be like living off Bingo's money because this will be his by virtue of the gift, but he depends on Andy pridefully rejecting the offer and walking out on Bingo once and for all. What he doesn't depend on is Andy grabbing the check with a threat to flaunt it (and a former girlfriend) at the party where Bingo plans to announce their engagement and call it a bribe to make him quit her. What Andy doesn't expect is that Bingo will respond to this scene by shooting him. Fortunately the bullet only grazes his collarbone; it's the kind of wound that makes shooter and victim realize how much they still love each other. But if that wasn't a fatal blow to the audience, now Murchison decides that if Andy wants to work and earn the means to support Bingo, there's a mine-engineering job available, for which Andy just happens to have the college qualifications. That's one head-slapping way to close a movie, since you can only ask why Murchison didn't offer Andy that job in the first place.

There's no guaranteeing that Untamed would have been any good if it had continued along the lines of its first half-hour, but the way it did continue guaranteed that critics would declare it brain-dead. A Pittsburgh reviewer called it "the most amazing burlesque ever to come from the sometimes deluded wanderings of a scenario writer," and I don't think I can top that.

You can see where this is going, and the idea of the looming, lunkish Torrence, who made his name as a psycho hillbilly in Tol'able David and was rendered still more exotic by sound's exposure of his Scots burr -- acting as Bingo's Henry Higgins to make her fit for society has some potential. Unfortunately, Untamed doesn't go there. Instead, her social education is presented as a fait accompli so the picture can take up a new subject. On the boat back to America Bingo had met cute with Andy McAllister (Robert Montgomery), who unfortunately already has a date for the voyage. That doesn't stop Bingo, who after bopping her rival on the nose on the ship hooks up with Andy again in New York, where practically the last untamed thing Bingo does is goad Andy and a rival suitor into a boxing match in the middle of a swanky party at her mansion. From this point, Untamed really becomes Andy's story, driven by a male-pride melodrama. The young man has been bred for society but has no immediate prospects. This means that, should he marry Bingo, he won't be able to give her the lifestyle to which she has but recently become accustomed. For Bingo this isn't a problem, as she doesn't see why they couldn't live off her money, as managed by Murchison. This is where male pride comes in; it would be shameful for Andy to live off his wife, especially when Murchison suspects him of being a gigolo -- even though the straitlaced old man can't bring himself to utter the word. Recognizing that psychology at work in Andy, Murchison tries to manipulate him out of Bingo's life by appearing to consent to a wedding while offering Andy a "wedding gift" of $30,000. He sweet-talks Andy, assuring him that it won't be like living off Bingo's money because this will be his by virtue of the gift, but he depends on Andy pridefully rejecting the offer and walking out on Bingo once and for all. What he doesn't depend on is Andy grabbing the check with a threat to flaunt it (and a former girlfriend) at the party where Bingo plans to announce their engagement and call it a bribe to make him quit her. What Andy doesn't expect is that Bingo will respond to this scene by shooting him. Fortunately the bullet only grazes his collarbone; it's the kind of wound that makes shooter and victim realize how much they still love each other. But if that wasn't a fatal blow to the audience, now Murchison decides that if Andy wants to work and earn the means to support Bingo, there's a mine-engineering job available, for which Andy just happens to have the college qualifications. That's one head-slapping way to close a movie, since you can only ask why Murchison didn't offer Andy that job in the first place.

There's no guaranteeing that Untamed would have been any good if it had continued along the lines of its first half-hour, but the way it did continue guaranteed that critics would declare it brain-dead. A Pittsburgh reviewer called it "the most amazing burlesque ever to come from the sometimes deluded wanderings of a scenario writer," and I don't think I can top that.

Thursday, July 21, 2016

I KNEW HER WELL (Io la conoscevo bene, 1965)

Fifty years after starring in Antonio Pietrangeli's film, Stefania Sandrelli offered what may be the best critique of it. Her character, the aspiring actress Adriana, jumps to her death from her upper-floor apartment at the end of the picture, no longer being able to cope with the humiliations of her existence. If it seems like an overdetermined moment to you, Sandrelli seems to agree. She doesn't think Adriana had to die, or necessarily would have killed herself, but "she had to die for the film to end." But if Io la conoscevo bene closes on a false note, there aren't many others in Pietrangeli's scathing satire. In many ways -- its episodic structure, its social surrealism -- it seems like a critique of Federico Fellini, its point being that la vita isn't so dolce for those less privileged than Marcello Mastroianni's characters. To the extent that Adriana's career is apparently ruined on a whim by a spiteful filmmaker, it takes a shot at the possibly misogynist vanities of 8 1/2 as well.

Adriana is a striver, first seen as a clumsy stylist -- literally first seen sunning herself on a garbage-strewn beach, actually -- who longs to be on screen. She has an agent who lands her dubious assignments that at least pay some bills, from shoe model for a TV commercial to traveling funiture ad on the roof of a car to fashion model during the intermission of a boxing card staged at an opera house, with some vast classical tapestry as a backdrop. For her these are important stepping stones, but others find her ambitions absurd. Why did she dress up so elaborately for the shoe commercial, for instance, when she'll only be seen from the ankles down?

Our heroine is just another rat in a hopeless race, it seems, and both she and the film itself are sympathetic to people in a similar plight like the good-natured boxer Lunk (a clean-shaven Mario Adorf), who gets battered on a regular basis because it's the only way he can earn money. His path and Adriana's cross all too briefly, but despite her apparent affinity for simpler, sweeter people like the local auto mechanic (Franco Nero), her ambition draws her into the orbit of less lovable losers. Gigi Baggini (Ugo Tognazzi) is a has-been and hanger-on with a big star who makes him perform a grueling tap dance at a party Adriana attends. Later, the star uses Gigi as a go-between with Adriana. When Adriana tells Gigi to have his master ask her out himself, in his own desperation not to take the blame, Gigi reports that Adriana simply rejected the idea of a date. That doesn't help Gigi, who's last seen desperately clinging to the great man's car, begging for a break, but his lie leads to Adriana's ruin. She was at the party in part to film an interview with the star that will be included in a newsreel to promote her career. Out of spite, the star edits the interview into an atrocity out of Merton of the Movies, portraying Adriana as an idiot and a slut with the bad taste to wear a plaster on the heel of her foot. Adriana doesn't see it coming, having gathered with her fellow usherettes at the local movie house to watch her big moment, only to be laughed out of the building. From there, for all intents and purposes, her fate is sealed.

I still can't help feeling that the film has her give up too easily -- she seems capable of greater perseverance -- but I suppose satire has its prerogatives, and the film has been fine enough up to this point for me to hold the ending against it too much. It isn't called I Know Her Well, after all, so we should have seen this coming. Whether it's past or present tense, the moral seems to be that no one knew her well, or ever will, though some may think they did. Whether Adriana really knew herself, or was simply playing a role at the fatal moment, is a question the film invites you to answer for yourselves.

Adriana is a striver, first seen as a clumsy stylist -- literally first seen sunning herself on a garbage-strewn beach, actually -- who longs to be on screen. She has an agent who lands her dubious assignments that at least pay some bills, from shoe model for a TV commercial to traveling funiture ad on the roof of a car to fashion model during the intermission of a boxing card staged at an opera house, with some vast classical tapestry as a backdrop. For her these are important stepping stones, but others find her ambitions absurd. Why did she dress up so elaborately for the shoe commercial, for instance, when she'll only be seen from the ankles down?

Our heroine is just another rat in a hopeless race, it seems, and both she and the film itself are sympathetic to people in a similar plight like the good-natured boxer Lunk (a clean-shaven Mario Adorf), who gets battered on a regular basis because it's the only way he can earn money. His path and Adriana's cross all too briefly, but despite her apparent affinity for simpler, sweeter people like the local auto mechanic (Franco Nero), her ambition draws her into the orbit of less lovable losers. Gigi Baggini (Ugo Tognazzi) is a has-been and hanger-on with a big star who makes him perform a grueling tap dance at a party Adriana attends. Later, the star uses Gigi as a go-between with Adriana. When Adriana tells Gigi to have his master ask her out himself, in his own desperation not to take the blame, Gigi reports that Adriana simply rejected the idea of a date. That doesn't help Gigi, who's last seen desperately clinging to the great man's car, begging for a break, but his lie leads to Adriana's ruin. She was at the party in part to film an interview with the star that will be included in a newsreel to promote her career. Out of spite, the star edits the interview into an atrocity out of Merton of the Movies, portraying Adriana as an idiot and a slut with the bad taste to wear a plaster on the heel of her foot. Adriana doesn't see it coming, having gathered with her fellow usherettes at the local movie house to watch her big moment, only to be laughed out of the building. From there, for all intents and purposes, her fate is sealed.

I still can't help feeling that the film has her give up too easily -- she seems capable of greater perseverance -- but I suppose satire has its prerogatives, and the film has been fine enough up to this point for me to hold the ending against it too much. It isn't called I Know Her Well, after all, so we should have seen this coming. Whether it's past or present tense, the moral seems to be that no one knew her well, or ever will, though some may think they did. Whether Adriana really knew herself, or was simply playing a role at the fatal moment, is a question the film invites you to answer for yourselves.

Tuesday, July 19, 2016

Serial Pulp: THE SPIDER'S WEB (1938), Chapter Four: Surrender or Die!

At the end of Chapter Three of this Columbia Pictures adaptation of Norvell Page's pulp hero, Richard Wentworth was knocked into a mean looking power-plant thingy that turned explosive on impact. At the opening of this chapter, after the narrator's usual long-winded recap -- he has to talk over all the footage from last week's climax -- Wentworth, aka The Spider, simply gets better and gets out of Dodge when the cops show to disrupt The Octopus's plan to black out the city. By now, Wentworth has figured out that The Octopus is no common gangster, but represents "organized crime with more than money as a goal. He wants control." He specifically wants control of utilities, having first muscled into transportation and more recently targeted electrical power. That The Octopus is engaged in "terrorism" rather than mere crime is in keeping with the apocalyptic tone of the Popular Publications pulps, though whether the villain can keep escalating his attacks like his print counterparts remains to be seen.

Out of nowhere Wentworth gets a potentially important lead from a young friend of his, the gas station operator and ham radio enthusiast Charlie Dennis. In The Spider's day a ham radio operator was as close as you could get to a computer hacker today, and Charlie has inadvertently hacked into the Herzen Band, a frequency outside the range of most radios on which the gas jockey is picking up inscrutable, apparently coded transmissions. Wentworth transcribes a typical broadcast and has his old war buddy Jackson set about deciphering the code. Charlie has instantly become an important asset for the good guys, but The Octopus's men have detected the hack somehow, and their master orders Charlie eliminated. So we have this episode's plot wrapped up: The Spider will have to save Charlie from the bad guys....except that he doesn't. In fact, Wentworth and his pals are completely clueless about Charlie's imminent doom and make no effort to protect what could have been a crucial source of intelligence on The Octopus's activities. In a flawless victory for the villain, Charlie is murdered and his gas station (and all-important radio) blown up with Wentworth none the wiser.

The main characters never even acknowledge that anything has happened to poor Charlie, though I have to imagine that the Herzen Band will become important again later. To be fair, our heroes have their own security to think about, since The Octopus's goons are still stalking Wentworth. Two of them jump Richard outside his hotel suite. He fights them off but finds that Nita and Jackson, whom he'd left in the suite, have been snatched, the snatchers leaving behind a note telling Richard to expect a message from The Octopus.

The mystery villain has several balls in the air. While trying to outmaneuver Wentworth, he's also plotting to take out all the city's radio stations so he can monopolize the airwaves when making his demands. The broadcast gives Wentworth and Ram Singh a chance to use their triangulation machines to pinpoint the source of the transmission, which they expect to be The Octopus's lair and their friends' prison. Finding the likely spot, they break through an electrified fence and prepare for a two-pronged attack on the building. Despite being warned to be careful, the mighty Ram Singh promptly gets KOd while skulking in the bushes and joins Nita and Jackson in chains in a cell.

This place proves to be some kind of torture house. The cell is rigged to fill with water in order to drown its prisoners.While they thrash about in vain and the water rises, The Spider enters another end of the house and surprises a bunch of gangsters. For some reason he surrenders his advantage of surprise to hunker behind a toppled table, content to trade shots with the surviving goons until one quick-thinking, courageous bad guy closes a door to trap The Spider in a room with a gas bomb. As if that wasn't bad enough, this room is rigged to release a lethal volume of steam. A double cliffhanger closes an episode that has not gone well for the good guys. It's good at holding our interest, however, since it shows The Octopus and his men as more effective serial villains than we typically see. We'll see how long that lasts....

Out of nowhere Wentworth gets a potentially important lead from a young friend of his, the gas station operator and ham radio enthusiast Charlie Dennis. In The Spider's day a ham radio operator was as close as you could get to a computer hacker today, and Charlie has inadvertently hacked into the Herzen Band, a frequency outside the range of most radios on which the gas jockey is picking up inscrutable, apparently coded transmissions. Wentworth transcribes a typical broadcast and has his old war buddy Jackson set about deciphering the code. Charlie has instantly become an important asset for the good guys, but The Octopus's men have detected the hack somehow, and their master orders Charlie eliminated. So we have this episode's plot wrapped up: The Spider will have to save Charlie from the bad guys....except that he doesn't. In fact, Wentworth and his pals are completely clueless about Charlie's imminent doom and make no effort to protect what could have been a crucial source of intelligence on The Octopus's activities. In a flawless victory for the villain, Charlie is murdered and his gas station (and all-important radio) blown up with Wentworth none the wiser.

The main characters never even acknowledge that anything has happened to poor Charlie, though I have to imagine that the Herzen Band will become important again later. To be fair, our heroes have their own security to think about, since The Octopus's goons are still stalking Wentworth. Two of them jump Richard outside his hotel suite. He fights them off but finds that Nita and Jackson, whom he'd left in the suite, have been snatched, the snatchers leaving behind a note telling Richard to expect a message from The Octopus.

The mystery villain has several balls in the air. While trying to outmaneuver Wentworth, he's also plotting to take out all the city's radio stations so he can monopolize the airwaves when making his demands. The broadcast gives Wentworth and Ram Singh a chance to use their triangulation machines to pinpoint the source of the transmission, which they expect to be The Octopus's lair and their friends' prison. Finding the likely spot, they break through an electrified fence and prepare for a two-pronged attack on the building. Despite being warned to be careful, the mighty Ram Singh promptly gets KOd while skulking in the bushes and joins Nita and Jackson in chains in a cell.

This place proves to be some kind of torture house. The cell is rigged to fill with water in order to drown its prisoners.While they thrash about in vain and the water rises, The Spider enters another end of the house and surprises a bunch of gangsters. For some reason he surrenders his advantage of surprise to hunker behind a toppled table, content to trade shots with the surviving goons until one quick-thinking, courageous bad guy closes a door to trap The Spider in a room with a gas bomb. As if that wasn't bad enough, this room is rigged to release a lethal volume of steam. A double cliffhanger closes an episode that has not gone well for the good guys. It's good at holding our interest, however, since it shows The Octopus and his men as more effective serial villains than we typically see. We'll see how long that lasts....

Sunday, July 17, 2016

DVR Diary: BENGAZI (1955)

They didn't add the h (for Hillary?) until later, but this is the Libyan city of 21st century infamy, back in the early days after World War II when the former Italian colony was under Anglo-French occupation. But John Brahm's adventure film from the last days of RKO could have been set in any colonial place for all the attention it pays to natives. It's a slightly noirish treasure hunt as some disreputable veterans and a seedy saloon owner head into the desert, where a ruined mosque hides the gold one of the gang stole from local tribesmen. Our hero, if only by default, is John Gilmore, a refugee from small town America, where it's a big event when the local movie theater changes its program once a week. His ball and chain is the bar owner, Donovan (an elderly Victor McLageln), who seems incapable of backing up whatever bluster he can still manage. He wants in on the treasure so he can take care of his daughter back on the Emerald Isle, but unbeknownst to him she (Mala Powers) has come to Bengazi looking for him. They haven't seen each other for so long that they blow right past each other in their first encounter, and it's not until Gilmore finds out her name that he arranges a proper reintroduction. Once the three-man gang goes into the desert, the daughter joins a Scots officer (Richard Carlson with a wobbly accent) in pursuit by plane. In the mosque, the third partner is almost immediately killed by virtually invisible tribesmen, while Gilmore and Donovan hunker down for a siege. Reinforcements are actually the last thing they need, especially since Donovan's daughter and the officer promptly get their plane blown up after they've landed. The intruders are picked off one by one -- there are expendable people I haven't mentioned, and McLageln is mercifully eliminated relatively early -- until Gilmore learns some moral lesson and decides to sacrifice the treasure, if not himself, in order to save the final girl and the wounded officer. Apart from some creative use of the ruined mosque set and the plane landing in the desert Brahm doesn't take much advantage of the Superscope wide screen and Bengazi overall seems much like the sort of programmer that might have been made ten or fifteen years earlier. Conte's a good actor who always managed to retain some dignity throughout his career, but McLageln is embarrassing if not pitiful, clearly having nothing left at this late point in his career. The picture's too-good-to-be-true ending is a final insult to the viewer, but I suppose we could wish everyone's problems in Libya could be solved so easily.

Wednesday, July 13, 2016

Serial Pulp: THE SPIDER'S WEB (1938), Chapter Three: High Voltage

The resolution of last episode's cliffhanger was set up when we saw Richard Wentworth's henchman Ram Singh monitoring the situation in the Adams office as Wentworth, The Spider, prepared to rescue his girlfriend Nita Van Sloan. Once the faithful Sikh saw that The Octopus's men had set a deathtrap for The Spider, he rushed to the building. After the recap, this episode opens with Ram arriving just in time to help fellow flunky Jackson get the mechanical hoist back in control so Nita and The Spider have an easy last leg of their trip to the ground. After seeing Nita off, The Spider re-enters the building to fetch Adams from a vault in order to interrogate him about The Octopus. As he drives away, more minions take up the pursuit. The Spider exhorts Adams to jump from the car before it goes over a cliff, but Adams is no Spider and burns with the vehicle.

Inevitably, The Spider is blamed for the neophyte traction magnate's murder, provoking a hissy fit from Wentworth."All because a few thugs are killed, the cry goes up: Get the Spider!" he complains, "Every time The Spider strikes, all they see is the act. Never a thought for the real reason behind it." Wentworth is more thin-skinned a crimefighter than The Green Hornet, for instance, who wants to be thought of as a criminal, since that makes it easier for him to move through the underworld. But pity party over, it's back to work. "I've got to find the Octopus, and destroy him," our hero resolves.

Civilian life is no shelter for Richard Wentworth as it is for other costumed crimefighters. Since Wentworth himself is known as a criminologist who gets involved in prominent cases, he is just as much a target out of costume as The Spider is. The Octopus has known since the last chapter that Wentworth is an enemy, so he has the Wentworth house staked out, with gunsels waiting to blast Wentworth the moment he steps outside. Fortunately for our team, The Octopus's minions are idiots. Richard dodges them by ordering a bouquet of "special flowers" for Nita from a friendly, confidential florist. The delivery made, Wentworth swaps clothes with the delivery man and marches out to the delivery truck, a leftover bouquet obscuring his face as the bored gunsels watch. "This is a useless job," one reflects, but if this serial teaches us anything it's that there are no useless jobs, only useless people.

Wentworth puts on his Blinky McQuade disguise to seek out a gangster he'd recognized among the men in Adams' office. Blinky, the one-eyed safecracker, will be hard up and looking for any kind of job Frank Martin can give him. McQuade is perhaps the most likable gangster you'll ever meet, and Martin gladly lets him in on a warehouse job his gang is pulling on their own. If that goes well, Martin may use him on an Octopus job. Martin says Blinky can be trusted not to blab about things, but you'd think he'd wonder after the cops show up in the middle of the warehouse job. To be fair, it isn't clear if Wentworth called in a tip once Blinky found out where the job was, and in any event a wounded Martin is too grateful to think too much about things after Blinky rescues him from arrest by sticking up a cop with his finger.

Once Martin tells him what the Octopus has lined up -- a raid on a power plant in an effort to black out the city -- Blinky arranges to have Jackson show up at his hideout in a cop costume to take him in for questioning. "The Octopus ordered this job done so there wouldn't be a light left on in the city," a gangster helpfully explains to the audience and the men gathered not at all conspicuously or suspiciously outside the Power & Light company. The Spider shows up, guns blazing, to break up the sabotage, but has the bad luck to get socked into a great big spark-emitting machine to end the episode. Of course, Columbia spoils the cliffhanger by telling us immediately what Wentworth will be up to next time, but I suppose if you knew going in that there would be fifteen chapters you could guess that the hero wouldn't get whacked in Episode Three. It makes you wonder why serial studios bothered with cliffhangers. If you think about it, take away the cliffhangers and instead of Saturday afternoon serials you have the modern short-form TV season -- except now you can watch any episode of some shows and really believe a hero might die.

Some of Richard Wentworth's victims bear "the mark of The Spider."

Inevitably, The Spider is blamed for the neophyte traction magnate's murder, provoking a hissy fit from Wentworth."All because a few thugs are killed, the cry goes up: Get the Spider!" he complains, "Every time The Spider strikes, all they see is the act. Never a thought for the real reason behind it." Wentworth is more thin-skinned a crimefighter than The Green Hornet, for instance, who wants to be thought of as a criminal, since that makes it easier for him to move through the underworld. But pity party over, it's back to work. "I've got to find the Octopus, and destroy him," our hero resolves.

Civilian life is no shelter for Richard Wentworth as it is for other costumed crimefighters. Since Wentworth himself is known as a criminologist who gets involved in prominent cases, he is just as much a target out of costume as The Spider is. The Octopus has known since the last chapter that Wentworth is an enemy, so he has the Wentworth house staked out, with gunsels waiting to blast Wentworth the moment he steps outside. Fortunately for our team, The Octopus's minions are idiots. Richard dodges them by ordering a bouquet of "special flowers" for Nita from a friendly, confidential florist. The delivery made, Wentworth swaps clothes with the delivery man and marches out to the delivery truck, a leftover bouquet obscuring his face as the bored gunsels watch. "This is a useless job," one reflects, but if this serial teaches us anything it's that there are no useless jobs, only useless people.

Wentworth puts on his Blinky McQuade disguise to seek out a gangster he'd recognized among the men in Adams' office. Blinky, the one-eyed safecracker, will be hard up and looking for any kind of job Frank Martin can give him. McQuade is perhaps the most likable gangster you'll ever meet, and Martin gladly lets him in on a warehouse job his gang is pulling on their own. If that goes well, Martin may use him on an Octopus job. Martin says Blinky can be trusted not to blab about things, but you'd think he'd wonder after the cops show up in the middle of the warehouse job. To be fair, it isn't clear if Wentworth called in a tip once Blinky found out where the job was, and in any event a wounded Martin is too grateful to think too much about things after Blinky rescues him from arrest by sticking up a cop with his finger.

Once Martin tells him what the Octopus has lined up -- a raid on a power plant in an effort to black out the city -- Blinky arranges to have Jackson show up at his hideout in a cop costume to take him in for questioning. "The Octopus ordered this job done so there wouldn't be a light left on in the city," a gangster helpfully explains to the audience and the men gathered not at all conspicuously or suspiciously outside the Power & Light company. The Spider shows up, guns blazing, to break up the sabotage, but has the bad luck to get socked into a great big spark-emitting machine to end the episode. Of course, Columbia spoils the cliffhanger by telling us immediately what Wentworth will be up to next time, but I suppose if you knew going in that there would be fifteen chapters you could guess that the hero wouldn't get whacked in Episode Three. It makes you wonder why serial studios bothered with cliffhangers. If you think about it, take away the cliffhangers and instead of Saturday afternoon serials you have the modern short-form TV season -- except now you can watch any episode of some shows and really believe a hero might die.

To be continued...

Monday, July 11, 2016

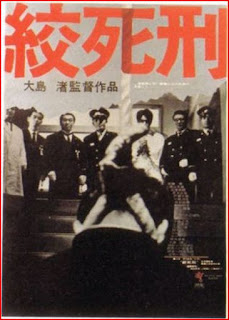

DEATH BY HANGING (1968)

Death by hanging in Japan means death by strangulation, or else Nagisa Oshima's admittedly magical-realist satire wouldn't even get started. Death By Hanging would be a very different movie if everyone in the audience assumed that the condemned man's neck should have been broken. Instead, the trouble starts when the man's heart keeps beating beyond all expectation. The officials aren't sure if "R" (Do-yun Yu) should be hung a second time, given their assumption that they're actually dealing with some sort of revenant. R, a rapist and murderer, recognizes some of the officials when he wakes up but claims to have no recollection of his crimes. His Christian chaplain speculates that R's soul has left his body, which means this soul-less but sentient husk should not be hanged again. The other officials, all involved with law enforcement, agree that R has to regain his memories and recognize his guilt before he can be hung a second time. The main action of Oshima's black comedy is the blundering effort to reawaken R's identity, from his wretched background as a Korean immigrant to his carnal lust for his victim. This mock-epic attempt at recovering memories takes the cast from the newspapered walls of an imagined Korean hovel to the rooftops of Tokyo as a reenacted seems to turn all too real.

The director's not-so-subtle message is (in part) that R's original identity was shaped in the first place by the same sort of national prejudices that make the officials look like bigoted idiots, not to mention the very circumstance of being a Korean in Japan. From the way they act when restaging R's family life, Koreans are the n-words of Japan, viewed through a prism of minstrelsy as a rabble of slobbovian morons who piss on each other during family arguments. Having the Japanese act out their stereotypes of Koreans may be the best way to subvert those stereotypes, and it's definitely one of the funniest parts of an often-hilarious movie. As a black comedy it's like Dr. Strangelove in microcosm, with the stakes reduced to one life but with the cartoonish cast behaving just as ludicrously, or even more so in proportion to the situation.

Death By Hanging is a kind of companion piece to Oshima's previous film, the one with the unfortunate English title Sing a Song of Sex. Despite the bawdy title, that film is an ominous, brilliant portrait of Japan on a precipice of revolt and reaction in the form of rape. In turn, despite its ominous English title, Death By Hanging revels in its absurdity and even throws in a Japanese bawdy song of the sort that superficially formed part of Sing a Song's subject matter. In both movies Oshima seems to be indicting a bawdy streak in Japanese culture that seems inherently reactionary and oppressive (not to mention complacent) insofar as it helps shape R's carnal lust and makes women eligible for the sort of rape the officials so casually or sometimes enthusiastically reenact.

Death also renews an interest in Christianity that Oshima had expressed in his 1962 historical epic The Christian Revolt.It's apropos given the popularity of Christianity among Koreans, which makes it almost natural for Oshima to imagine R, who is based on a real-life convict who wrote a famous book of prison letters before his execution, as a Christ figure who has to die a second time, or as often as possible, for the imagined sins of Koreans as a race. Jesus's saying that he who imagines himself committing sin is just as guilty as if he had committed the actual act is pointedly invoked, with an Oshima twist that indicts those who imagine others committing sins like rape, as if R was fulfilling a Japanese expectation of carnal violence from Koreans. Any supposed Korean proclivity for rape or other crimes thus becomes a projection of Japanese culture's own yen for such atrocities. In effect, Oshima suggests, condemned Koreans, if not all condemned men, die a second death as the nation reassures itself that the dead deserved what they got, while their victims did not. That seems to be the point of the apparition (Akiko Koyama) who calls herself R's sister and tempts him to see his crime as a revolt against Japanese oppression. That the Japanese on some level buy into that interpretation seems apparent from the way the officials one by one start to see the sister when most of them hadn't at first. Eventually, there's an even more urgent need to "liquidate" this accusing ghost than there is to reawaken R's guilt. R's turn finally comes after the chief prosecutor, the one official who's retained some dignity throughout, dares him to leave the prison if he thinks himself innocent. R can't do it because he realizes he can't be innocent in Japan, even as he claims that he isn't guilty in the way the Japanese portray his guilt. In the end he accepts the noose again and the trapdoor opens beneath him, to reveal an empty noose below like the empty sepulcher of Christian myth. Perhaps this second death has exorcised whatever of R had haunted his executioners, but you can easily imagine an eternal recurrence of these scenes despite R's hope to die for the sake of all the other Rs. Death By Hanging can be heavyhanded at times but Oshima mostly succeeds at his Brechtian work of thought-provoking absurdity. The more I see of his films from the Sixties, the more it seems like one of the great bodies of work in the wild world of cinema.

Sacrilege: a drunken Christian priest loses his inhibitions and lunges for a singing partygoer's strap-on.

Death By Hanging is a kind of companion piece to Oshima's previous film, the one with the unfortunate English title Sing a Song of Sex. Despite the bawdy title, that film is an ominous, brilliant portrait of Japan on a precipice of revolt and reaction in the form of rape. In turn, despite its ominous English title, Death By Hanging revels in its absurdity and even throws in a Japanese bawdy song of the sort that superficially formed part of Sing a Song's subject matter. In both movies Oshima seems to be indicting a bawdy streak in Japanese culture that seems inherently reactionary and oppressive (not to mention complacent) insofar as it helps shape R's carnal lust and makes women eligible for the sort of rape the officials so casually or sometimes enthusiastically reenact.

Death also renews an interest in Christianity that Oshima had expressed in his 1962 historical epic The Christian Revolt.It's apropos given the popularity of Christianity among Koreans, which makes it almost natural for Oshima to imagine R, who is based on a real-life convict who wrote a famous book of prison letters before his execution, as a Christ figure who has to die a second time, or as often as possible, for the imagined sins of Koreans as a race. Jesus's saying that he who imagines himself committing sin is just as guilty as if he had committed the actual act is pointedly invoked, with an Oshima twist that indicts those who imagine others committing sins like rape, as if R was fulfilling a Japanese expectation of carnal violence from Koreans. Any supposed Korean proclivity for rape or other crimes thus becomes a projection of Japanese culture's own yen for such atrocities. In effect, Oshima suggests, condemned Koreans, if not all condemned men, die a second death as the nation reassures itself that the dead deserved what they got, while their victims did not. That seems to be the point of the apparition (Akiko Koyama) who calls herself R's sister and tempts him to see his crime as a revolt against Japanese oppression. That the Japanese on some level buy into that interpretation seems apparent from the way the officials one by one start to see the sister when most of them hadn't at first. Eventually, there's an even more urgent need to "liquidate" this accusing ghost than there is to reawaken R's guilt. R's turn finally comes after the chief prosecutor, the one official who's retained some dignity throughout, dares him to leave the prison if he thinks himself innocent. R can't do it because he realizes he can't be innocent in Japan, even as he claims that he isn't guilty in the way the Japanese portray his guilt. In the end he accepts the noose again and the trapdoor opens beneath him, to reveal an empty noose below like the empty sepulcher of Christian myth. Perhaps this second death has exorcised whatever of R had haunted his executioners, but you can easily imagine an eternal recurrence of these scenes despite R's hope to die for the sake of all the other Rs. Death By Hanging can be heavyhanded at times but Oshima mostly succeeds at his Brechtian work of thought-provoking absurdity. The more I see of his films from the Sixties, the more it seems like one of the great bodies of work in the wild world of cinema.

Saturday, July 9, 2016

Serial Pulp: THE SPIDER'S WEB (1938), Chapter Two: Death Below

We left Richard Wentworth, aka The Spider, attempting to drive a truck loaded with explosives away from a bus depot. The first chapter of the Columbia Pictures serial based on Popular Publications' pulp crimefighter ended with the truck blowing up, but chapter two opens (after the obligatory recap, heavy with narration) with an easy cheat: our hero simply dived out the opposite door of the truck before it blew. After dealing with The Octopus's men, The Spider now has to dodge the police who consider him a criminal. He carjacks someone and hops from the moving vehicle into Ram Singh's getaway car some safe distance from the cops.

The Spider then calls in a tip telling Police Commissioner Kirk to raid the Octopus hideout where Wentworth had been imprisoned briefly last episode. Wentworth himself shows up just before the raid and manages to lead his friend Kirk into a deathtrap. The doors and windows lock just after someone tosses in a gas bomb to kill the crimefighters. Wentworth figures that short-circuiting the room by shooting a light-switch will unlock the window, and he and Kirk take the fire escape out.

After things have calmed down, Wentworth checks in at the commissioner's office, where he's meeting with an impatient committee of businessmen who want results from the hunt for the mastermind terrorizing transportation, whose name remains unknown to the good guys. While all these people are big businessmen, they missed one detail in the business news section of the newspaper that Wentworth reads: J. R. Adams, an unknown in the business world, has been named the new head of the Roberts Bus Line, Roberts having been murdered last chapter. Wentworth figures that Adams is either the head terrorist himself or one of his stooges. After asking the businessmen to leave the office, Wentworth discusses his plans for dealing with Adams in detail with the commissioner. Right away, we see The Octopus tell his hooded minions that he expects Wentworth to make a move on Adams and will make plans to deal with Wentworth. This seems like a tip-off that The Octopus -- as you'll recall, we see him as a bulky, limping figure in white robes, hood and mask and hear him through a distorting speaker system -- is one of the big businessmen, or else in cahoots with one of them.

Wentworth isn't satisfied with bugging Adams' office. He and his minion Jackson infiltrate the place as telephone men, and while Wentworth attempts to distract the secretary -- on screen it looks like he's doing a poor job -- Jackson inconspicuously installs a television camera hidden inside a book. By "inconspicuously," I mean that Jackson shows the movie camera the camera embedded in the book, then opens the book to show us all the machinery inside, while we take it on faith that the secretary hasn't noticed any of this.

Back at chez Wentworth, Richard, Jackson and Ram Singh turn out the lights in their TV room to watch the J. R. Adams show, after the set takes a minute to warm up. Right away someone asks Adams what the latest orders are, but he doesn't know apart. However, Wentworth now knows he's dealing with The Octopus, who checks in via intercom soon enough to explain conveniently that he intends to take over "certain industries," warn Adams about Wentworth, and provide some protection in the form of a hostage: Nita Van Sloan fresh from the hospital and still in her aviatrix outfit from chapter one. Wentworth and the boys freak out at the sight and Ram Singh is ready to kill, but you'll notice that Nita takes it all like a trouper, showing neither fear nor any other emotion, very much like an actress who's been given no direction whatsoever in the scene.

Jackson delivers The Spider to the Adams building, where our hero hops on a mechanical hoist so Jackson can send him straight up to the villain's floor. There's a hint of pulp flair to the shot of The Spider poised on the chain outside a window, his cape billowing more dramatically (if not necessarily more manageably) than Batman's in the same studio's infamous 1943 serial. Entering through the window, he kills a guard by knocking him into an electrified doorknob and prepares to enter Adams's office. Inside, Adams's goons are prepared to blast whoever comes through the door, or else blast the still-impassive Nita. The Spider enters, using the dead guard as a human shield. The goons are so shocked by this atrocity that Nita nimbly steps out of the kill box while her enemies stare helplessly. The Spider forces the bad guys to lock themselves in a vault, but he and Nita still have to dodge goons coming upstairs. Out the window they go so they can ride earthward on the hoist, but when Jackson has to fight another goon the hoist slips out of control and Spita (to make a ship of it) begin to plunge at deadly speed, and now Nita screams....

This episode left me wondering what purpose poor Adams was supposed to serve. Obviously he was only going to be a front for The Octopus, but was he appointed only to get Wentworth's attention with his obvious lack of credentials? As for The Octopus, what exactly was his plan to deal with Wentworth? Was it simply to retain Nita as a hostage in case Wentworth showed up, or did he know about the hidden camera after all and had her paraded in front of the camera to draw Wentworth back to the building and its feeble trap? Whatever you make of it, it seems like a waste of his time to focus on Wentworth when he should be consolidating his gains from last episode, but that's serial logic for you. Maybe our villain will have something better to do in chapter three, "High Voltage," coming soon to this blog.

The Spider then calls in a tip telling Police Commissioner Kirk to raid the Octopus hideout where Wentworth had been imprisoned briefly last episode. Wentworth himself shows up just before the raid and manages to lead his friend Kirk into a deathtrap. The doors and windows lock just after someone tosses in a gas bomb to kill the crimefighters. Wentworth figures that short-circuiting the room by shooting a light-switch will unlock the window, and he and Kirk take the fire escape out.

After things have calmed down, Wentworth checks in at the commissioner's office, where he's meeting with an impatient committee of businessmen who want results from the hunt for the mastermind terrorizing transportation, whose name remains unknown to the good guys. While all these people are big businessmen, they missed one detail in the business news section of the newspaper that Wentworth reads: J. R. Adams, an unknown in the business world, has been named the new head of the Roberts Bus Line, Roberts having been murdered last chapter. Wentworth figures that Adams is either the head terrorist himself or one of his stooges. After asking the businessmen to leave the office, Wentworth discusses his plans for dealing with Adams in detail with the commissioner. Right away, we see The Octopus tell his hooded minions that he expects Wentworth to make a move on Adams and will make plans to deal with Wentworth. This seems like a tip-off that The Octopus -- as you'll recall, we see him as a bulky, limping figure in white robes, hood and mask and hear him through a distorting speaker system -- is one of the big businessmen, or else in cahoots with one of them.

Wentworth isn't satisfied with bugging Adams' office. He and his minion Jackson infiltrate the place as telephone men, and while Wentworth attempts to distract the secretary -- on screen it looks like he's doing a poor job -- Jackson inconspicuously installs a television camera hidden inside a book. By "inconspicuously," I mean that Jackson shows the movie camera the camera embedded in the book, then opens the book to show us all the machinery inside, while we take it on faith that the secretary hasn't noticed any of this.

This episode left me wondering what purpose poor Adams was supposed to serve. Obviously he was only going to be a front for The Octopus, but was he appointed only to get Wentworth's attention with his obvious lack of credentials? As for The Octopus, what exactly was his plan to deal with Wentworth? Was it simply to retain Nita as a hostage in case Wentworth showed up, or did he know about the hidden camera after all and had her paraded in front of the camera to draw Wentworth back to the building and its feeble trap? Whatever you make of it, it seems like a waste of his time to focus on Wentworth when he should be consolidating his gains from last episode, but that's serial logic for you. Maybe our villain will have something better to do in chapter three, "High Voltage," coming soon to this blog.

Wednesday, July 6, 2016

Serial Pulp: THE SPIDER'S WEB (1938), Chapter One: Night of Terror

For some people, pulp fiction is embodied by crimefighting heroes like Doc Savage and The Shadow. They're the two best known of a generation of pulp heroes that flourished in the 1930s, before and during the advent of comic book superheroes. One of their peers was The Spider, "Master of Men," who was published by Popular Publications, while the big two were put out by Street & Smith. Among the most popular hero pulps, The Spider was the first to be made into a movie serial, not long after The Shadow had made his unsuccessful feature-film debut. In pulp, The Spider's adventures were written mostly by Norvell W. Page, using the Grant Stockbridge pseudonym. I find Page the best of the hero-pulp writers, the master of the often overwrought Walter Gibson (who wrote The Shadow as Maxwell Grant) and the often clumsy Lester Dent (who wrote Doc Savage as Kenneth Roberson). Page could paint a word picture of dramatic if not fantastic action better than his rivals, and his apocalyptic imagination makes The Spider resonate with modern readers in ways his rivals can't match. Of course, what Page wrote might be called "destruction porn" today, because The Spider's enemies don't play around. They're usually terrorists of some sort rather than mere gangsters, for whom mass destruction is the way to power or the way to wealth through mass extortion. Cities were devastated and civilians slaughtered before the Spider meted out justice to the guilty; like comic-book heroes today, The Spider wasn't very good at preventing mayhem. He was better at assuring that people didn't get away with it. Richard Wentworth was The Spider, but unlike the Zorro-Batman archetype, Wentworth also fought crime in his civilian identity as an amateur criminologist and often spent large portions of Spider stories doing so out of disguise. Wentworth had a modest support team consisting of his chauffeur Jackson, his butler Jenkins, his all-around man friday Ram Singh and his fiancee Nita Van Sloan. No relation to Edward the actor, Nita often bemoans the apparent fact that Richard's costumed career prevents them from marrying -- presumably since it would be impracticable for them to have children -- but for all intents and purposes she embraces his lifestyle to the point of pinch-hitting as The Spider on occasion. She may not have the same sort of training Richard and his other helpers have, but a machine gun is often a great equalizer and she can use one with relish. Rounding out the regular cast is Police Commissioner Kirkpatrick, a friend of Wentworth who suspects him of being The Spider, whom he'd have to arrest as a killer vigilante, but never can prove the dual identity.

Serials notoriously wrought havoc on comic-book heroes, altering origins and other details to suit often unclear purposes. By comparison, at least on the evidence of Chapter One, The Spider's Web is fairly faithful to its pulp source. Its major innovation is the costume The Spider (Warren Hull) wears. While the pulp character often scurried through the city in a fright wig and makeup to scarify criminals, he was shown on the magazine covers in more debonair garb and a modest domino mask. The cinematic Spider wears a full face mask with a spiderweb pattern matching that of his cape. He has his full supporting cast, though the police commish's name has been shortened arbitrarily to Kirk. Nita (Iris Meredith) makes a good first impression as co-pilot of Wentworth's private plane as they're returning home from some vacation. She actually expects to be married, since Richard has resolved to give up being The Spider. An attempt to sabotage their landing soon changes his mind, and Nita takes the disappointment like a good sport.

The sabotage was perpetrated by minions of The Octopus (??? in Chapter One), who sees Wentworth the criminologist as an obstacle to his plan to control all transportation and thus apply a stranglehold to the entire national economy. The Octopus is a classic serial mystery villain, someone whose identity under his white hood we'll be invited to guess over the remaining chapters. He walks with a limp, afflicted with a shriveled leg that's almost certainly a bit of misdirection. He speaks into a microphone and his voice is amplified (and distorted, no doubt) by speakers in his office, where black-hooded minions report and await orders.

Like the typical Spider villain, The Octopus takes no prisoners; at the climax of Chapter One he plots to blow up a bus depot, but The Spider manages to evacuate the place simply by showing up and terrorizing commuters with his presence. In case that didn't suffice, he and Ram Singh (future Ed Wood collaborator Kenne "Kenneth" Duncan, playing the man from India with no hint of an accent) have a gunfight with the Octopus's gang, including -- it's my guess since he isn't credited -- a very young John Dehner. The bomb is on a bus that The Spider tries to drive a safe distance from the building and any civilians, but he doesn't get the thing a safe distance from himself. Of course, then as now, the teaser for the next episode assures us, as if serial audiences needed such assurance, that Richard Wentworth will survive to face new crises next week.

The Spider's Web intends to highlight Richard Wentworth as a master of disguise. In the opening credits Warren Hull is introduced thrice over, as Wentworth, The Spider, and his one-eyed underworld alias Blinky McQuade. Wentworth also briefly amuses Nita with a vaudevillian Chinaman bit. While Wentworth is shown to be a quick-change artist, Hull will depend on his vocal versatility to put over his different guises. He has a charming moment in this chapter while changing into Blinky when he has a little conversation between two of his personalities. If people thought the Spider one of the nuttier pulp heroes, that moment won't dissuade them, but it does give the hero more character than the typical serial protagonist. Hull may not have the authentic Spider's cold fury, but he makes a likable action hero and, to be fair, this story is just getting started. Stay tuned for more chapters through the month of July, or get ahead of the game by watching the serial yourself at the Internet Archive.

Serials notoriously wrought havoc on comic-book heroes, altering origins and other details to suit often unclear purposes. By comparison, at least on the evidence of Chapter One, The Spider's Web is fairly faithful to its pulp source. Its major innovation is the costume The Spider (Warren Hull) wears. While the pulp character often scurried through the city in a fright wig and makeup to scarify criminals, he was shown on the magazine covers in more debonair garb and a modest domino mask. The cinematic Spider wears a full face mask with a spiderweb pattern matching that of his cape. He has his full supporting cast, though the police commish's name has been shortened arbitrarily to Kirk. Nita (Iris Meredith) makes a good first impression as co-pilot of Wentworth's private plane as they're returning home from some vacation. She actually expects to be married, since Richard has resolved to give up being The Spider. An attempt to sabotage their landing soon changes his mind, and Nita takes the disappointment like a good sport.

The sabotage was perpetrated by minions of The Octopus (??? in Chapter One), who sees Wentworth the criminologist as an obstacle to his plan to control all transportation and thus apply a stranglehold to the entire national economy. The Octopus is a classic serial mystery villain, someone whose identity under his white hood we'll be invited to guess over the remaining chapters. He walks with a limp, afflicted with a shriveled leg that's almost certainly a bit of misdirection. He speaks into a microphone and his voice is amplified (and distorted, no doubt) by speakers in his office, where black-hooded minions report and await orders.

The Spider's Web intends to highlight Richard Wentworth as a master of disguise. In the opening credits Warren Hull is introduced thrice over, as Wentworth, The Spider, and his one-eyed underworld alias Blinky McQuade. Wentworth also briefly amuses Nita with a vaudevillian Chinaman bit. While Wentworth is shown to be a quick-change artist, Hull will depend on his vocal versatility to put over his different guises. He has a charming moment in this chapter while changing into Blinky when he has a little conversation between two of his personalities. If people thought the Spider one of the nuttier pulp heroes, that moment won't dissuade them, but it does give the hero more character than the typical serial protagonist. Hull may not have the authentic Spider's cold fury, but he makes a likable action hero and, to be fair, this story is just getting started. Stay tuned for more chapters through the month of July, or get ahead of the game by watching the serial yourself at the Internet Archive.

Sunday, July 3, 2016

On the Big Screen: THE LEGEND OF TARZAN (2016)

Every generation, it seems, tries to remake Tarzan in its own image. No matter how obsolete or politically incorrect Edgar Rice Burroughs' creation is thought to have become, someone dimly remembers the money Tarzan made in the past and tries to make him a moneymaker again. This newest attempt at a live-action Tarzan seems to be doing better than the most recent previous efforts, judging at least by the box-office reports. Craig Brewer and Adam Cozad's screenplay wisely leaves Tarzan in the past; if anything, they backdate his career somewhat, if you assume that Burroughs set the present-day events of his original novel in the year he published it, 1912. The Legend of Tarzan is set in 1890, by which time John Clayton III (Alexander Skarsgård) has returned from Africa to claim his heritage as Lord Greystoke and become a media celebrity, to his own apparent embarrassment. Whatever actually happened in Africa, and despite Clayton's current fluency in English, "Me Tarzan, You Jane" apparently is a thing in 1890 England, if not the wider English-speaking world, as American diplomat George Washington Williams (Samuel L. Jackson) bluntly reminds the young lord. Williams explains to Greystoke that King Leopold of Belgium has invited the former Tarzan to his Congo Free State in order to publicize his humanitarian anti-slavery efforts by exploiting Greystoke's celebrity. It's only when Williams privately adds that Leopold's publicity is a fraud, and that the Belgian is doing the opposite of what he claims, that Greystoke decides to accept the invitation in order to facilitate the American's own investigation. Of course, Tarzan can't return to Africa without Jane (Margot "Harley Quinn" Robbie) demanding to accompany him. After all, according to this film's major retcon, Jane Porter, a missionary's daughter, was born and raised in Africa and may be on better terms with the natives than Tarzan himself.

All of this is very convenient to King Leopold's agent in the Congo, Leon Rom (Christoph Waltz), who has been told by an African chief (Djimoun Hounsou, increasingly typed as a bad guy) that he can have all the diamonds he wants from fabled Opar for the bankrupt King on the sole condition that he deliver Tarzan for some sort of vengeance. It looks like an easy transaction when Rom promptly captures Tarzan, but when Williams and some local tribesmen manage to free the ape man the Belgian has to fall back on Plan B: kidnap Jane and depend on Tarzan to pursue him to the chief's territory. Plan B takes longer but works better. The only problem is that the chief doesn't get his revenge, though the audience learns why he wants it. Instead, Tarzan takes his revenge on Rom with help from approximately all the animals in Africa....