Sacrilege: a drunken Christian priest loses his inhibitions and lunges for a singing partygoer's strap-on.

Death By Hanging is a kind of companion piece to Oshima's previous film, the one with the unfortunate English title Sing a Song of Sex. Despite the bawdy title, that film is an ominous, brilliant portrait of Japan on a precipice of revolt and reaction in the form of rape. In turn, despite its ominous English title, Death By Hanging revels in its absurdity and even throws in a Japanese bawdy song of the sort that superficially formed part of Sing a Song's subject matter. In both movies Oshima seems to be indicting a bawdy streak in Japanese culture that seems inherently reactionary and oppressive (not to mention complacent) insofar as it helps shape R's carnal lust and makes women eligible for the sort of rape the officials so casually or sometimes enthusiastically reenact.

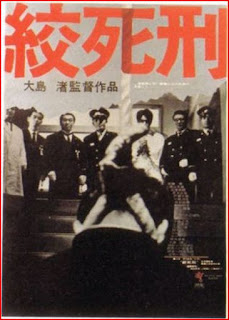

Death also renews an interest in Christianity that Oshima had expressed in his 1962 historical epic The Christian Revolt.It's apropos given the popularity of Christianity among Koreans, which makes it almost natural for Oshima to imagine R, who is based on a real-life convict who wrote a famous book of prison letters before his execution, as a Christ figure who has to die a second time, or as often as possible, for the imagined sins of Koreans as a race. Jesus's saying that he who imagines himself committing sin is just as guilty as if he had committed the actual act is pointedly invoked, with an Oshima twist that indicts those who imagine others committing sins like rape, as if R was fulfilling a Japanese expectation of carnal violence from Koreans. Any supposed Korean proclivity for rape or other crimes thus becomes a projection of Japanese culture's own yen for such atrocities. In effect, Oshima suggests, condemned Koreans, if not all condemned men, die a second death as the nation reassures itself that the dead deserved what they got, while their victims did not. That seems to be the point of the apparition (Akiko Koyama) who calls herself R's sister and tempts him to see his crime as a revolt against Japanese oppression. That the Japanese on some level buy into that interpretation seems apparent from the way the officials one by one start to see the sister when most of them hadn't at first. Eventually, there's an even more urgent need to "liquidate" this accusing ghost than there is to reawaken R's guilt. R's turn finally comes after the chief prosecutor, the one official who's retained some dignity throughout, dares him to leave the prison if he thinks himself innocent. R can't do it because he realizes he can't be innocent in Japan, even as he claims that he isn't guilty in the way the Japanese portray his guilt. In the end he accepts the noose again and the trapdoor opens beneath him, to reveal an empty noose below like the empty sepulcher of Christian myth. Perhaps this second death has exorcised whatever of R had haunted his executioners, but you can easily imagine an eternal recurrence of these scenes despite R's hope to die for the sake of all the other Rs. Death By Hanging can be heavyhanded at times but Oshima mostly succeeds at his Brechtian work of thought-provoking absurdity. The more I see of his films from the Sixties, the more it seems like one of the great bodies of work in the wild world of cinema.

No comments:

Post a Comment