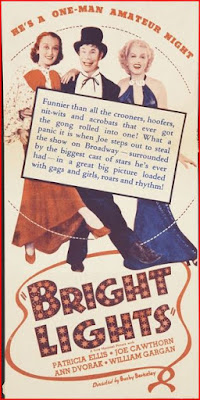

Busby Berkeley's comedy is a star vehicle for Joe E. Brown, Warner Bros.' leading comic of the pre-Code era, that makes a half-hearted try at being a newer kind of comedy. Acknowledging the rapid evolution within a year or so of what came to be called screwball comedy, Bright Lights grafts an already-standard feature of screwball, the "madcap heiress," onto the Brown project. Claire Whitmore (Patricia Ellis) apparently flits around the country doing whatever pricks her fancy, generating headlines whenever she's discovered. Reporter Dan Wheeler (William Gargan) discovers her working as a chorus girl in a burlesque theater where Joe Wilson (Brown) is the star comic. Wilson does an act with his wife Fay (Ann Dvorak) in which she sings while he, playing a drunk, heckles her from a balcony. Wilson combines insult humor and daredevil physical comedy; wandering the balcony to interact with audience members (or plants?), he constantly teeters on the railing until, challenged by the singer to show some talent of his own, he swings from a curtain rope Tarzan-style onto the stage, hitting the curtain and sliding down to join Fay in a soft-shoe routine. Berkeley makes the most of these scenes, shooting from angles that emphasize the (illusory) threat to the star while taking advantage of Brown's athleticism. The star does his own crucial stunt to climax the act, starting in close-up on the balcony and swinging into the curtain and sliding down. Berkeley then cuts to the stage to get a close shot of Brown landing and doing a forward roll, ending up on his feet and ready to dance. The director can trust his star later in the film to chase and then be chased by an airplane at an airport, and to hit the ground at the right moment for the plane to take off over his head. Brown gets to do the sort of things in his films, particularly those where he plays an athlete, that Buster Keaton should have been doing in sound films. Brown, however, was more of an all-around entertainer than Keaton, if less a creature of pure cinema, and Bright Lights highlights his versatility, showcasing not only his physical talent but other elements, like his drunk act and his baby talk storytelling, that probably haven't aged as well.

Brown himself is no screwball comic, though he's best remembered today for his comparatively screwball turn as an addled millionaire in Some Like It Hot. Apart from the madcap-heiress angle, Bright Lights could have been made years earlier. Tipped off by Wheeler, the producer of Anderson's Frolics hires the Wilsons and Whitmore for the latest edition of his Broadway show. Joe is ecstatic to hit the big time, but determined that Fay share the spotlight with him. When Anderson (Henry O'Neill) insists on pairing Joe with Whitmore for maximum publicity, Joe turns him down flat and is willing to sacrifice his chance at stardom, but Wheeler convinces Fay to nobly sacrifice her own ambitions so Joe can get his chance. She claims to be happy to live a life of luxury, complete with Arthur Treacher as the archetypal servant, but when the Wilsons' old burlesque producer needs an extra hand on the road, she jumps at the chance. Meanwhile, gullible Joe can't help falling for Whitmore, without realizing that she loves Wheeler. He finally sees the truth just after mailing a Dear Jane letter to Fay, prompting a final epic chase as Joe pursues the letter from mailbox to postoffice to airport to Akron, where Fay is performing. Inevitably, the film is far more star vehicle than screwball film, with the madcap heiress as little more than a plot complication, and while it's arguably more "Joe E. Brown, the Motion Picture" than his other vehicles, he's lively and likable enough to put it all over, with much help from Berkeley, who demonstrates here that he could direct a realistic backstage musical nearly as well as he managed his more famous flights of mass-choreographed fancy. Bright Lights catches Brown at or near the height of his popularity, but his star would dim by decade's end as the pretty faces of screwball eclipsed the grotesque nut comics of Brown's heyday.

A randomly comprehensive survey of extraordinary movie experiences from the art house to the grindhouse, featuring the good, the bad, the ugly, but not the boring or the banal.

Sunday, March 8, 2020

Tuesday, March 3, 2020

THE GIANT OF MARATHON (La battaglia di Maratona, 1959)

People may still know that the length of the modern marathon race is based on the distance from the Persian War battlefield of Marathon to ancient Athens, and that a messenger from the battlefield, having run the distance, dropped dead immediately after announcing the Athenian victory. If so, those same people may take Jacques Tourneur's peplum (assisted by Mario Bava) as the ultimate travesty, since the runner lives and gets the girl at the end of the picture. For the record, however, the legend of Phillipides dates back only to the second century of the Common Era, something like 500 years after the facts. Herodotus, the great historian of the war, mentions no such dying messenger. Tourneur, Bava et al really are no less entitled to exercise artistic license than the Roman writer Lucian was. Their writers thus make even more of Phillipides (Steve Reeves), who in their account is a peasant landowner whose past heroism against the Persians earns him leadership of the mythical Athenian Sacred Guard and a rallying point for supporters of the city-state's still-fledgling democracy. There remains an anti-democratic opposition that hopes for the restoration by Persia of exiled tyrant Hippias. Leading the opposition in the city is Theocritus (Sergio Fantoni), who schemes to co-opt Phillipides by marrying him off to the courtesan Charis (Daniela Rocca). Our hero already has his eye on blond, athletic Andromeda (Mylene Demongeot), the daughter of Theocritus' friend Creuso (Ivo Garrani). Phillipides can't be swerved from resistance, however, and Theocritus gradually alienates everyone before taking refuge with Hippias and the Persian army. Crucially, the bad guys fail to double-tap Charis after putting an arrow in her back when she tries to escape to warn the Athenians. She comes the nearest to performing the familiar Philippidean feat, while Philippides himself saves his energy for fighting. Marathon is noteworthy for having unusually good battle scenes for a peplum. I don't know whether Tourneur, Bava, or some second-unit person deserves the credit for this, but credit is definitely due given how feeble the genre's battle scenes often are. Strangely enough, Marathon climaxes with a sea battle, showing off a decent budget with full-scale ships and an underwater-attack sequence, along with a captive Andromeda sort of living up to her mythic namesake by being tied to the prow of a Persian ship. Steve Reeves's films apparently got bigger budgets in the wake of the global success of his Hercules films, and while he is what he is -- clean-shaven this time -- the money and a certain creative enthusiasm shows even in a faded pan-and-scan print on digital cable. It's hardly history, but it's fun on a matinee-movie level without being overblown in all the ways you'd expect from a more recent film.

Saturday, February 29, 2020

On the Big Screen: THE TRAITOR (Il traditore, 2019)

At age eighty, and after more than fifty years of filmmaking Marco Bellocchio is arguably the elder statesman of Italian cinema. In the 21st century he's become an intermittent chronicler of Italy's 20th century. His latest film is a companion piece with his 2009 Mussolini film Vincere and his 2003 Aldo Moro-Red Brigades picture Good Morning Night. The "traitor" of this one is Tommaso Buscetta (Pierfrancesco Pavino), Italy's answer to Joe Valachi: the first man who spilled the beans on organized crime in his country in a major way. This happened in the 1980s, after Buscetta, a career criminal and ex-con, decided to leave the business and move to Brazil, where he had done "business" before. Relatives who remain in Italy, including two sons, are killed in a Mafia war, while the Brazilian government accuses him of drug trafficking. The Brazilian government of the day didn't play around; they try to force a confession by threatening to throw Tommaso's wife (Maria Fernanda Candido) from a helicopter into the ocean. Whether he had anything to confess or not, Buscetta ends up back in Italy, where he decides that he has actual stuff to confess to crusading prosecutor and eventual martyr Giovanni Falcone (Fausto Russo Alesi). He becomes the star witness at the so-called Maxi Trial, which becomes the film's central spectacle. For non-Italians, the unusual trial procedures stand out, particularly allowing defendants to cross-examine witnesses. This makes possible dramatic confrontations between Buscetta and his former colleagues, who naturally call him a liar when they aren't heckling him as a cuckold from their cages in the rear of the vast courtroom. Buscetta holds his own in these encounters -- though he fares less well later when he lobs accusations at politicians who clearly can afford better lawyers than mafiosi can -- but he hardly can enjoy his victories when the bosses are convicted. He knows all too well that the Mafia's reach and memory are long. Exiled in an American witness-protection program, he retreats from New Hampshire to Colorado after a restaurant singer in a Santa costume serenades him in Sicilian dialect as if he were the coward Robert Ford. To the day of his peaceful demise he has to remain on guard, because he knows the Mafia like he knows himself....

Accustomed as U.S. audiences have become to expansive, seemingly comprehensive Scorsese-style chronicles of crime, Il Traditore can't help seeming incomplete no matter how well made and performed it mostly is. We're likely to become conscious of gaps or omissions as Buscetta clarifies his motives for informing. He tells Falcone and the judges at the Maxi Trial that he still considers himself a "man of honor" but that his peers, particular Salvatore Riina (Nicola Cali) were the true traitors to the traditional values of La Cosa Nostra by going all in on the heroin trade, regardless of its cost to their own families. Something can't help but seem missing when Buscetta repeatedly reiterates how Riina has ruined La Cosa Nostra, yet Riina has a relatively minimal presence in the film and we see very little of the "golden age" Buscetta idealizes -- which we definitely would see in a Scorsese epic -- before Riina took over. Rather than show this idealized past, Bellocchio challenges us to take Bruscetta's word for it or question his actual motivation. The director presents the past in non-linear fashion rather than giving us a conventional rise-and-fall narrative. The film's flashbacks aren't self-consciously narrated by Bruscetta, but arrive more like unfiltered memories, though one important reminiscence midway through the picture is interrupted and only taken up again at the very end. An exception to the general rule is a flashback to the murder of Buscetta's sons, based on the testimony of a new informer who took part in the killing. This scene, and Buscetta's reaction to the testimony, suggest guilt over abandoning his children to almost certain death as the his ultimate motive, since his indifference to whether they joined him in Brazil belies his claim that his real family ultimately mattered more to him than the Mafia family. In the end, I think, Bellocchio is too careful to offer a perfect "Rosebud" explanation for Buscetta's "treason." He keeps a certain distance from his subject that is arguably European if only by comparison to Hollywood's insistence on definitive answers. Overall, I rather like Favino's performance for its comparative understatement. He makes Buscetta seem like a real person rather than an archetype. I don't know if Favino and Bellocchio have given us the "real" Buscetta -- alternate presentations seem possible -- but they did make me want to know more about the man, and that should count as some kind of success.

Accustomed as U.S. audiences have become to expansive, seemingly comprehensive Scorsese-style chronicles of crime, Il Traditore can't help seeming incomplete no matter how well made and performed it mostly is. We're likely to become conscious of gaps or omissions as Buscetta clarifies his motives for informing. He tells Falcone and the judges at the Maxi Trial that he still considers himself a "man of honor" but that his peers, particular Salvatore Riina (Nicola Cali) were the true traitors to the traditional values of La Cosa Nostra by going all in on the heroin trade, regardless of its cost to their own families. Something can't help but seem missing when Buscetta repeatedly reiterates how Riina has ruined La Cosa Nostra, yet Riina has a relatively minimal presence in the film and we see very little of the "golden age" Buscetta idealizes -- which we definitely would see in a Scorsese epic -- before Riina took over. Rather than show this idealized past, Bellocchio challenges us to take Bruscetta's word for it or question his actual motivation. The director presents the past in non-linear fashion rather than giving us a conventional rise-and-fall narrative. The film's flashbacks aren't self-consciously narrated by Bruscetta, but arrive more like unfiltered memories, though one important reminiscence midway through the picture is interrupted and only taken up again at the very end. An exception to the general rule is a flashback to the murder of Buscetta's sons, based on the testimony of a new informer who took part in the killing. This scene, and Buscetta's reaction to the testimony, suggest guilt over abandoning his children to almost certain death as the his ultimate motive, since his indifference to whether they joined him in Brazil belies his claim that his real family ultimately mattered more to him than the Mafia family. In the end, I think, Bellocchio is too careful to offer a perfect "Rosebud" explanation for Buscetta's "treason." He keeps a certain distance from his subject that is arguably European if only by comparison to Hollywood's insistence on definitive answers. Overall, I rather like Favino's performance for its comparative understatement. He makes Buscetta seem like a real person rather than an archetype. I don't know if Favino and Bellocchio have given us the "real" Buscetta -- alternate presentations seem possible -- but they did make me want to know more about the man, and that should count as some kind of success.

Sunday, February 9, 2020

Too Much TV: BATWOMAN (2019 - ?)

Speaking of superheroes, the CW's newest DC Comics show has predictably been renewed for a second season. The bad news is that Batwoman doesn't emulate Black Lightning in departing from Greg Berlanti formulae, often looking like an utterly generic Berlanti CW show. The character is a natural for Berlanti, I suppose, since the modern version of Batwoman was heralded from her introduction in 2006 as DC Comics' first openly-gay superhero. The Batwoman show hasn't gone out of its way to make homophobia its big bad (apart from its inescapable contribution to the character's origin story) the way Supergirl has constantly battled sexism and other forms of bigotry. Instead, it takes inspiration from the most successful storyline from the Batwoman comics, pitting protagonist Kate Kane (Ruby Rose) against her twin sister Beth (Rachel Skarsten), who has come back from seeming death as the Lewis Carroll-obsessed Alice, a psychopathic gang leader. How Beth became Alice differs depending on whether you read comics or watch TV, but the differences don't really matter that much and need not be described here. What really matters is that in comics the Batwoman creative team finished up with Alice and moved on, while there's no sign yet that the TV team plans to do likewise. That's because the idea of an antagonist who is also family is right up the CW's alley, and not something they're likely to let go of right away. One difference between comics and TV worth emphasizing is that, in comics, the reveal of Alice as Beth comes at the last moment before Alice's apparent demise, while on TV the reveal comes very early. The TV writers want the family thing to complicate Batwoman's battle constantly, just as drama involving other family members -- her dad runs a private army that has taken over much of Gotham City's policing, while her stepmother was involved in shady dealings before Alice killed her, and her stepsister resents Kate's obsession with Alice -- takes up much of the show's time. Like nearly all TV, Batwoman uses "family" as a shortcut to profundity, but the family angle with Alice also underscores the larger issue of how to deal with criminals in general that runs through all the Berlanti shows.

This Berlanti preoccupation was most obvious on Sunday nights last fall when both Batwoman and Supergirl had storylines involving criminals who were family. On Supergirl we learned that the Martian Manhunter's brother had gone over to the bad Martians back in the day because his family had cast him out, fearing a unique mental power he possessed. He appeared on Earth and became a menace to J'onn J'onnz and his friends until the Manhunter pacified him. Doing this required J'onn to come to terms with his own guilt in having wiped the brother out of his own and his father's memory out of fear, and to perform a risky act of submission -- or atonement, if you prefer -- to the aggrieved brother. All of this worked, of course, and the brother hasn't been a threat since then. Similarly, the Kane family have to deal with Beth/Alice's grievance against their having "abandoned" her, after a long, obsessive search, while she was the captive of a mad doctor. Kate herself always felt that her dad gave up the search too soon, and both she and her dad feel the guilts after learning that stepmom had created fake evidence of Beth's death to help them move on, as it were. The larger point here, it seems, is that Berlanti and his writers want society to recognize some role in the creation of seemingly evil people rather than treating them as inherently irredeemable bad seeds. They're not consistent about this, since some villains (e.g. Damian Darhk) are portrayed as cartoonishly, disposably evil, while the great exception that seems to prove the overall rule was Andy Diggle, the brother of Arrow sidekick John Diggle and henchman to the aforementioned Darhk, who defied all efforts at redemption and finally goaded his virtuous sibling to shoot him down in a fit of rage. His persistent viciousness actually made Andy a breath of fresh air in Berlanti-land, but the writers seem to see him as an experiment not to be repeated again. I suspect that Berlanti doesn't believe that anyone rally deserves death for the things they do. There's nothing wrong with that as a real-world political philosophy, but it does limit one's options in creating a dramatic fantasy world, and it also means that Batwoman probably will be hobbled for some time to come by its constant back-and-forth over what to do with Alice.

A little while ago, after Alice poisoned her stepmom, it seemed as if Kate had given up on trying to save her sister. But then the Crisis on Infinite Earths crossover happened and Batwoman received fresh indoctrination from the literal Paragon of Hope, Kara Zor-El, on not giving up on people. That pretty much assures us of more frustratingly repetitive dialogues between hero and villain and contrivances to keep Alice free, while the writers retain their option to make Alice's sidekick, the master of disguise called Mouse, the real big bad so Beth can be redeemed after all -- as, I'm compelled to admit, she eventually was in the comics, though by a different writer than her creator. It may be that a significant part of the DC/CW audience responds to this sort of drama the way Berlanti wants, but others may feel that the Alice story has gone on past its proper expiration date but has been sustained artificially to no good effect. The writers may feel vindicated by the show's renewal, however inevitable that may have been, but they shouldn't think themselves truly successful until they prove they can envision a future for Batwoman beyond Alice. To be fair, the Batwoman comic hasn't had much future beyond her -- the first series was canceled after the key creators quit over an editorial veto of Kate's marriage to another woman, based not on homophobia but on a dogmatic notion that superheroes should not be happy in their personal lives, and a second series was sadly short-lived -- so it's entirely possible that the TV show will give us the definitive Batwoman. To do so, it will have to move beyond where the comics have gone, but there's no sign yet that the writers are ready to do that.

This Berlanti preoccupation was most obvious on Sunday nights last fall when both Batwoman and Supergirl had storylines involving criminals who were family. On Supergirl we learned that the Martian Manhunter's brother had gone over to the bad Martians back in the day because his family had cast him out, fearing a unique mental power he possessed. He appeared on Earth and became a menace to J'onn J'onnz and his friends until the Manhunter pacified him. Doing this required J'onn to come to terms with his own guilt in having wiped the brother out of his own and his father's memory out of fear, and to perform a risky act of submission -- or atonement, if you prefer -- to the aggrieved brother. All of this worked, of course, and the brother hasn't been a threat since then. Similarly, the Kane family have to deal with Beth/Alice's grievance against their having "abandoned" her, after a long, obsessive search, while she was the captive of a mad doctor. Kate herself always felt that her dad gave up the search too soon, and both she and her dad feel the guilts after learning that stepmom had created fake evidence of Beth's death to help them move on, as it were. The larger point here, it seems, is that Berlanti and his writers want society to recognize some role in the creation of seemingly evil people rather than treating them as inherently irredeemable bad seeds. They're not consistent about this, since some villains (e.g. Damian Darhk) are portrayed as cartoonishly, disposably evil, while the great exception that seems to prove the overall rule was Andy Diggle, the brother of Arrow sidekick John Diggle and henchman to the aforementioned Darhk, who defied all efforts at redemption and finally goaded his virtuous sibling to shoot him down in a fit of rage. His persistent viciousness actually made Andy a breath of fresh air in Berlanti-land, but the writers seem to see him as an experiment not to be repeated again. I suspect that Berlanti doesn't believe that anyone rally deserves death for the things they do. There's nothing wrong with that as a real-world political philosophy, but it does limit one's options in creating a dramatic fantasy world, and it also means that Batwoman probably will be hobbled for some time to come by its constant back-and-forth over what to do with Alice.

A little while ago, after Alice poisoned her stepmom, it seemed as if Kate had given up on trying to save her sister. But then the Crisis on Infinite Earths crossover happened and Batwoman received fresh indoctrination from the literal Paragon of Hope, Kara Zor-El, on not giving up on people. That pretty much assures us of more frustratingly repetitive dialogues between hero and villain and contrivances to keep Alice free, while the writers retain their option to make Alice's sidekick, the master of disguise called Mouse, the real big bad so Beth can be redeemed after all -- as, I'm compelled to admit, she eventually was in the comics, though by a different writer than her creator. It may be that a significant part of the DC/CW audience responds to this sort of drama the way Berlanti wants, but others may feel that the Alice story has gone on past its proper expiration date but has been sustained artificially to no good effect. The writers may feel vindicated by the show's renewal, however inevitable that may have been, but they shouldn't think themselves truly successful until they prove they can envision a future for Batwoman beyond Alice. To be fair, the Batwoman comic hasn't had much future beyond her -- the first series was canceled after the key creators quit over an editorial veto of Kate's marriage to another woman, based not on homophobia but on a dogmatic notion that superheroes should not be happy in their personal lives, and a second series was sadly short-lived -- so it's entirely possible that the TV show will give us the definitive Batwoman. To do so, it will have to move beyond where the comics have gone, but there's no sign yet that the writers are ready to do that.

Saturday, February 8, 2020

On the Big Screen: BIRDS OF PREY AND THE FANTABULOUS EMANCIPATION OF ONE HARLEY QUINN (2020)

"I'm telling it all wrong!" Harley Quinn confesses well into her new film, and when the film itself admits this, what more can I say? This, I guess: any half hour of the Harley Quinn cartoon on the DC Universe streaming service is more entertaining than this sputtering too-late spinoff of the already-awful Suicide Squad. If its purpose was to make a franchise out of Margot Robbie's supporting cast then it has to be judged one of the most abject failures of recent times. If its purpose, however, was to make Jared Leto's Joker look worthy of comparison to Nicholson, Ledger and Phoenix in retrospect by inviting a more favorable comparison with Ewan McGregor's vacuous performance as Black Mask, then it's probably some sort of success -- presuming, of course, that anyone remembers Leto's Joker now. In all other respects the new film falls on its face, and early reports indicate that it won't even have the popular mandate Suicide Squad somehow enjoyed. Maybe people see it as a vanity project, fairly or not, and are steering clear, or maybe Harley Quinn's moment as a cultural phenomenon is already over. Maybe Warner Bros.' desire to treat her as DC's Deadpool is more desperately obvious now, or at least as obvious as the inability of anyone involved in the project to do a Deadpool. But incompetence isn't Birds of Prey's sin as much as indifference is. The story, to the extent that I remember it after a few hours -- something to do with a diamond somebody swallowed -- is just the inescapable something, the bare minimum the film has to have to get from one action scene to the next. The action scenes themselves are okay at best but way too choppy by the standard set by John Wick and Atomic Blonde without as many sight gags as an ostensible comedy-action film should have. You can't help feeling that more talented filmmakers could have done much more with the same characters and story -- a more linear approach would have helped, for starters -- but weren't considered necessary for something so seemingly pre-sold as a Harley Quinn movie. Joke's on them, it seems -- but at least Warner Bros. may be able to console themselves at the Oscars tomorrow. Maybe they can start fresh with Harley in a Joker sequel ....

Sunday, January 26, 2020

COLD WAR (Zimna wojna, 2018)

Pawel Pawlikowski's follow-up to Ida, though mostly praised by critics, didn't have the same impact in the U.S. as the earlier, Oscar-winning film. The lack of a Holocaust angle in the new film may be the simplest explanation for this, but Cold War itself may have been a little too foreign -- which is to say too nationalist -- for American art-house tastes. It marks a territory of tragic Polish exceptionalism that has no true home in either the Russian-dominated east or the American-dominated west, though the film has little or nothing to say about the U.S.A. or actual Americans. Instead, it asserts a nebulous Polish authenticity apparently incapable of true expression in the film's Cold War setting. The nebulous element finds form in the film's heroine, the aspiring singer Zula (Joanna Kulig), who pretends to be a peasant in order to join a folk-singing troupe organized in the late 1940s by musicologists Irena (Agata Kuleza) and Wiktor (Tomasz Kot). Wiktor falls in love with Zula, and the romance keeps him with the troupe after Irena quits in futile protest against the Communist government transforming it into a Stalinist propaganda vehicle. Its propaganda function allows the singers to tour the eastern bloc, including East Berlin, where Wiktor, as artistically frustrated as Irena, hopes to defect with Zula to the west. Alas, Zula never makes the rendezvous, so Wiktor defects alone.

Later in the 1950s, the troupe travels the wider world, and in Paris Zula encounters Wiktor again. Our hero will find a variety of work in the west, from composing film scores to playing in a niteclub jazz band. He still hopes to bring Zula to the other side, but his efforts to transform her into a jazz singer, including arranging a cool-jazz version of the folk tune that serves effectively as her theme song, only estrange them further. The issue isn't that she dislikes modern music -- she's seen dancing to "Rock Around the Clock" almost as a form of protest -- but that Wiktor is trying to make her into something she isn't for no good reason. Wiktor seems to realize this, too, and you could argue that for him she embodies the true Poland, to such a degree that he risks certain imprisonment in order to return home to be near her. In a melodramatic scenario mercifully underplayed by all involved, Wiktor can only be freed from prison by Zula marrying the party hack (Boris Szyc) who corrupted the folk troupe in the first place. In true melodramatic fashion, she becomes a lush until Wiktor finally emerges from prison, his artistic career apparently mangled (with his hand) beyond repair. With it already established that the west offers no real escape for them, the only remaining option is romantic suicide -- again carried out with respectable understatement. A point is made nevertheless, presumably one that found an appreciative audience in a newly-nationalist Poland. Cold War isn't exactly saying "a plague on both your houses," but it does say quite clearly that the freedom promised by the west wasn't really freedom, at least for some people -- or else that the west's freedom wasn't enough for some people. Wiktor seals his fate, against the advice of a harshly realistic Polish diplomat, with the explanation, "I'm Polish." What being Polish entails, if not what it actually means, is Cold War's ultimate subject, and it should be no surprise that, good as the film is -- strongly acted, sharply shot, admirably succinct -- it doesn't travel as well as Pawlikowski's previous effort. It should do no harm to his reputation, however, and whatever he does next is sure to be, most likely deservedly, an art-house event.

Later in the 1950s, the troupe travels the wider world, and in Paris Zula encounters Wiktor again. Our hero will find a variety of work in the west, from composing film scores to playing in a niteclub jazz band. He still hopes to bring Zula to the other side, but his efforts to transform her into a jazz singer, including arranging a cool-jazz version of the folk tune that serves effectively as her theme song, only estrange them further. The issue isn't that she dislikes modern music -- she's seen dancing to "Rock Around the Clock" almost as a form of protest -- but that Wiktor is trying to make her into something she isn't for no good reason. Wiktor seems to realize this, too, and you could argue that for him she embodies the true Poland, to such a degree that he risks certain imprisonment in order to return home to be near her. In a melodramatic scenario mercifully underplayed by all involved, Wiktor can only be freed from prison by Zula marrying the party hack (Boris Szyc) who corrupted the folk troupe in the first place. In true melodramatic fashion, she becomes a lush until Wiktor finally emerges from prison, his artistic career apparently mangled (with his hand) beyond repair. With it already established that the west offers no real escape for them, the only remaining option is romantic suicide -- again carried out with respectable understatement. A point is made nevertheless, presumably one that found an appreciative audience in a newly-nationalist Poland. Cold War isn't exactly saying "a plague on both your houses," but it does say quite clearly that the freedom promised by the west wasn't really freedom, at least for some people -- or else that the west's freedom wasn't enough for some people. Wiktor seals his fate, against the advice of a harshly realistic Polish diplomat, with the explanation, "I'm Polish." What being Polish entails, if not what it actually means, is Cold War's ultimate subject, and it should be no surprise that, good as the film is -- strongly acted, sharply shot, admirably succinct -- it doesn't travel as well as Pawlikowski's previous effort. It should do no harm to his reputation, however, and whatever he does next is sure to be, most likely deservedly, an art-house event.

Sunday, January 19, 2020

QUEEN OF THE HIGH SEAS (Le Avventure di Mary Read, 1961)

Best known for horror films, Umberto Lenzi began his career making period swashbucklers, starting with this 1961 outing inspired by the crossdressing pirate of the Caribbean, Mary Read. The film takes almost nothing from the little actually reported about Read, apart from her being a pirate and occasionally dressing in men's clothes. Her cohorts Anne Bonny and Jack Rackham don't appear in this picture, which seems to be set a few generations before Read's own time. Mary (Lisa Gastoni) is introduced in England as an aspiring master thief, attended by mentor/sidekick Mangiatrippa (Agostino Salvietti). Temporarily taken prisoner, she meets cute, within the confines of her male disguise, with wastrel aristocrat Peter Goodwin (Jerome Courtland). Goodwin will later be tasked with taking down the infamous pirate Captain Poof, not knowing that this is none other than Mary, whose true identity he eventually discovers. It wasn't always this way; once upon a time, believe it or not, there was a man named Captain Poof, but having accepted Mary as part of his crew, there soon was not enough room on his ship for two domineering personalities. Almost as a matter of course, Mary kills Poof and takes his place and his name. Having already proven herself an omnicompetent sailor, she soon demonstrates her mastery of pirate strategy to a crew initially reluctant to transgress beyond Poof's privateering mandate. In time, "Captain Poof" becomes the terror of all nations, but Mary eventually must choose to love or kill Peter Goodwin. Queen actually was Gastoni's Italian film debut, the Italo-Irish actress having spent her teen years in England and breaking into film there. She went on to do a number of swashbucklers, as well as some of Antonio Margheriti's sci-fi films, and I'm curious now to see whether those later films followed Queen's example and allowed Gastoni to be an action heroine. While the historical Read seems to have been little more than Jack Rackham's psycho doxy, Lenzi's protagonist is a virtual superwoman, at least by the standards of Sixties Euro-genre movies, as well as an irresistible charmer. Lenzi himself looks impressive as an (almost) first-time director. Whatever its budget, Queen appears to have better production values than many of Hollywood's soundstage-bound potboiler pirate movies of the previous decade. It may not have the intensity of violence Lenzi would later be known for, but it's still more energetic than many of its genre contemporaries. I suppose he would have been recognized as a promising talent, though the fulfillment of that promise would take forms unanticipated here.

Wednesday, January 15, 2020

Too Much TV: DRACULA (2020)

The creators of Sherlock claim that one purpose of their free adaptation of Bram Stoker's famous character -- to call their Dracula an adaptation of Stoker's novel may go too far -- is to make the king vampire the central character, "the hero of his own story" as it were. They then open their first of three episodes with a framing device ensuring that, as ever, we will see Dracula through Jonathan Harker's eyes. Harker tells his story at the convent where he takes shelter in the novel, to an irreverent nun (Dolly Wells) who apparently is the sister of Abraham Van Helsing, sharing his preoccupation with the undead. Harker (John Heffernan) as narrator is an unsettling sight, far more damaged than we're used to seeing, as if Deadpool had mated with a 1980s AIDS patient. This comes to seem appropriate as Harker endures a more severe ordeal than even Stoker had imagined through the hospitality of a rapidly-youthening Count (Claes Bang). This all begins quite promisingly; for much of the first hour co-writers Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat succeed at making a Dracula story feel more disquietingly Gothic than Stoker's novel by introducing the idea of a secret prisoner in Dracula's castle and later showing how the Count treats some of his victims as experiments. This sets the tone for the rest of the story, establishing that Dracula, after so many centuries, remains uncertain about exactly how his vampiric powers work and whether they're inherited by his "brides," female or male. But a discordant note begins to creep in as the vampire, absorbing Harker's knowledge by drinking his blood, starts talking in a familiarly glib, almost slangy way, calling his guest Johnny and generally sounding more and more like a standard 21st century charismatic villain. At the same time, commenting throughout on Harker's story, Sister Agatha tends to quip in drastic hit-or-miss fashion. The writings clearly aspire to accessibility at whatever cost, and the tone becomes too comic -- however fun it may be to hear Sister Agatha taunt Dracula near the end of the first episode -- for its own good. But I'm probably mistaking my own idea of its own good for its creators' intentions.

The second episode -- all three run approximately 90 minutes -- comes closest to the Dracula-as-central-character idea, though it also interposes a framing device, this time with Dracula narrating his famous voyage on the Demeter to a surprisingly friendly yet still skeptical Sister Agatha. This second episode is also the worst by far of the three, introducing a shipload of thinly sketched passengers for the vampire to victimize before Agatha breaks out of the framing device and reclaims the upper hand. Inclusiveness substitutes for substance here as the passenger list includes an Indian scientist and his mute daughter as well as the black gay lover of this episode's walking in-joke, the decadent Lord Ruthven. Yet this group may as well have come from a Russian novel of Stoker's time compared to the cartoon characters who pass for the Demeter's crew. They all amount to vampire fodder, of course, and with Dracula the focus rather than his victims his attacks are more reminiscent of Bugs Bunny's inevitable triumphs than they are horrific to any extent. It becomes less a question of which of the crew or passengers will survive than whether the viewers will survive -- and yet it's all nearly redeemed by the episode's closing twist.

The finale picks up threads of Stoker's story in the present day, as Dracula wakes from more than a century of recuperative slumber underwater to walk into a trap set nearly that long ago by a vampire-hunting organization founded by none other than Mina Murray, whom Dracula spared from a bad predicament at the end of the first episode for no apparent better reason than that the writers needed someone to found this organization. Working for this shadowy group is a familiar face: Zoe Helsing, Agatha's great-great-grandniece. She survives a vampire attack because her blood sickens the Count, for the all-too-mundane reason that she has terminal cancer. Other stories make dead people's blood potentially fatal to vampires, so this arguably is a modestly plausible leap forward. Zoe's organization wants to preserve Dracula and experiment on him, but they're thwarted by, of all things, a lawyer. Try and guess his name! After this presumably powerful, possibly malevolent organization meekly gives up its prisoner, the episode introduces us to a 21st century Lucy Westenra (Lydia West) and her familiar suitors -- minus one if the gay guy was supposed to be Arthur Holmwood. Dracula becomes obsessed with this reckless girl without really understanding why as we pick up the thread that may unravel the vampire after all. Just as he's never fully understood his own powers, this show proposes that Dracula has never understood, or at least hasn't fully come to terms with, his own nature. Inquisitive Agatha had wanted to know why Dracula fears Christian symbols -- apparently, their being holy never satisfied her inquiring mind, and in any event we'd seen another vampire in the first episode regard the same stuff without fear or pain -- and the Count's own half-baked idea that Christianity's bloody history makes the cross a symbol of death isn't satisfactory either. His fascination with Lucy -- who suffers an even more horrific fate than in the novel -- offers an important clue, but Zoe needs to drink Dracula's own blood in order to get insight from her feisty precursor Agatha. The resolution of all of this is weak: Dracula the mighty warrior, it turns, out, has always been ashamed of his own fear of death, and flinches from the traditional portents of his extinction -- the cross, the sun, etc. -- even when they won't hurt him at all, as Zoe/Agatha proves by aping Peter Cushing's heroics from Hammer's Horror of Dracula. So enlightened, our protagonist decides he may as well die. I'm not sure if that follows, but I suppose it effectively preempts any talk of another season -- unless, of course, the vampire rises to shrug, "Well, that didn't work!" and goes on about his business, should the ratings require it.

The second episode -- all three run approximately 90 minutes -- comes closest to the Dracula-as-central-character idea, though it also interposes a framing device, this time with Dracula narrating his famous voyage on the Demeter to a surprisingly friendly yet still skeptical Sister Agatha. This second episode is also the worst by far of the three, introducing a shipload of thinly sketched passengers for the vampire to victimize before Agatha breaks out of the framing device and reclaims the upper hand. Inclusiveness substitutes for substance here as the passenger list includes an Indian scientist and his mute daughter as well as the black gay lover of this episode's walking in-joke, the decadent Lord Ruthven. Yet this group may as well have come from a Russian novel of Stoker's time compared to the cartoon characters who pass for the Demeter's crew. They all amount to vampire fodder, of course, and with Dracula the focus rather than his victims his attacks are more reminiscent of Bugs Bunny's inevitable triumphs than they are horrific to any extent. It becomes less a question of which of the crew or passengers will survive than whether the viewers will survive -- and yet it's all nearly redeemed by the episode's closing twist.

The finale picks up threads of Stoker's story in the present day, as Dracula wakes from more than a century of recuperative slumber underwater to walk into a trap set nearly that long ago by a vampire-hunting organization founded by none other than Mina Murray, whom Dracula spared from a bad predicament at the end of the first episode for no apparent better reason than that the writers needed someone to found this organization. Working for this shadowy group is a familiar face: Zoe Helsing, Agatha's great-great-grandniece. She survives a vampire attack because her blood sickens the Count, for the all-too-mundane reason that she has terminal cancer. Other stories make dead people's blood potentially fatal to vampires, so this arguably is a modestly plausible leap forward. Zoe's organization wants to preserve Dracula and experiment on him, but they're thwarted by, of all things, a lawyer. Try and guess his name! After this presumably powerful, possibly malevolent organization meekly gives up its prisoner, the episode introduces us to a 21st century Lucy Westenra (Lydia West) and her familiar suitors -- minus one if the gay guy was supposed to be Arthur Holmwood. Dracula becomes obsessed with this reckless girl without really understanding why as we pick up the thread that may unravel the vampire after all. Just as he's never fully understood his own powers, this show proposes that Dracula has never understood, or at least hasn't fully come to terms with, his own nature. Inquisitive Agatha had wanted to know why Dracula fears Christian symbols -- apparently, their being holy never satisfied her inquiring mind, and in any event we'd seen another vampire in the first episode regard the same stuff without fear or pain -- and the Count's own half-baked idea that Christianity's bloody history makes the cross a symbol of death isn't satisfactory either. His fascination with Lucy -- who suffers an even more horrific fate than in the novel -- offers an important clue, but Zoe needs to drink Dracula's own blood in order to get insight from her feisty precursor Agatha. The resolution of all of this is weak: Dracula the mighty warrior, it turns, out, has always been ashamed of his own fear of death, and flinches from the traditional portents of his extinction -- the cross, the sun, etc. -- even when they won't hurt him at all, as Zoe/Agatha proves by aping Peter Cushing's heroics from Hammer's Horror of Dracula. So enlightened, our protagonist decides he may as well die. I'm not sure if that follows, but I suppose it effectively preempts any talk of another season -- unless, of course, the vampire rises to shrug, "Well, that didn't work!" and goes on about his business, should the ratings require it.

Monday, January 13, 2020

THE KING (2019)

He may not play the title character, but the true auteur of David Michôd's history play may well be its co-producer, co-writer and co-star, Joel Edgerton. The King is an innately audacious project: a do-over of the story of King Henry V of England, the subject not only of Shakespeare's play but of two highly acclaimed films made from the play: Laurence Olivier's of 1944 and Kenneth Branagh's of 1989. Edgerton, however, has assigned himself perhaps the most audacious task of all: a dramatic makeover of one of Shakespeare's most beloved characters, Sir John Falstaff. That puts Michôd and The King on a collision course with Orson Welles' Chimes at Midnight on top of its other challenges. Edgerton himself may have written the film's most audacious line, in which his Falstaff compares the fate Michôd and Edgerton have planned for him with a more ignominious finish which is pretty much what Shakespeare gave the character, and declares the King version the better ending. Except that Edgerton to a great extend underplays the role, his conception of Falstaff is what you might imagine Marlon Brando doing with the character, albeit without that actor's dubious British accent. That is, Edgerton and Michôd make Falstaff the conscience if not the outright hero of their story. The fat knight's aversion to combat is here more a matter of principle than it is in the original, in keeping with the new film's overall antiwar stance. But then Falstaff is shown to be the author of the winning strategy of the Battle of Agincourt, staking his own life on it by leading a virtually-suicidal feint intended to goad the French enemy into an even-more suicidal cavalry charge against English longbowmen on muddy terrain. For what it's worth, this Falstaff is neglected for a time but never publicly shunned by his old pal Prince Hal (Timothee Chalamet), who later resents the fat knight's refusal to commit war crimes but respects his counsel too much to hold it long against him. To each his own Falstaff, of course; Welles, selectively following the letter of Shakespeare, still made the character largely a mirror of himself. If Michôd and Edgerton's Falstaff seems sometimes like a mirror-universe version of Shakespeare's, the core idea of their conception seems to be the traditional fool who can tell a king the truth -- something the writers feel that Henry V desperately needed to hear.

The King's Henry shares Falstaff's aversion to mass slaughter, but is dangerously sensitive to personal slights that threaten his standing as a new, young heir to a usurping father. That makes Henry even more dangerously susceptible to manipulation by war-seeking advisers, particularly the Poloniesque William Gascoigne (Sean Harris), who manufactures conspiracies against Henry to be blamed on France and expendable colleagues. It doesn't help matters that the French Dauphin (Robert Pattinson in a critic-proof performance as a complete idiot) wants to get into some kind of pissing contest with the new king, or at least wants to fart in his general direction. Falstaff and later the French princess Catherine (Lily-Rose Depp) act as Henry's conscience against the tide of war, constantly questioning the need for war and reinforcing his own instinctual skepticism, born of resentment of the belligerent ways of his father (Ben Mendelsohn). Henry's the type who prefers to settle things by single combat when possible, as he does with the archetypal Hotspur rather than see his own brother waste an army and his own life in a pointless battle. A nice touch in this film is the way it shows Henry becoming Hotspur, i.e. the son his father really wanted despite Hotspur's treason. Another touch is the way that character arc ends with a parody of the early Hotspur fight, as the Dauphin challenges Henry to single combat after the big battle -- Michôd acquits himself fairly well in the shadow of past auteurs, by the way, and Chalamet works hard in long, violent takes -- but can't put one armored foot in front of the other without sprawling into the mud. The film ends with Catherine replacing Falstaff as Henry's good conscience and his evil counselors done away with all too neatly. But while it's all too obvious when actors are mouthpieces for the writers' opinions rather than real characters, and the film is absolutely not to be taken seriously as history, The King is a nicely made piece of work and mostly quite entertaining, especially if you're a sucker for historical epics like I am. It's just too bad that as a self-conscious alternative to the Shakespearean "Henriad," it's doomed to comparison with greater films instead of facing judgment on its own terms.

The King's Henry shares Falstaff's aversion to mass slaughter, but is dangerously sensitive to personal slights that threaten his standing as a new, young heir to a usurping father. That makes Henry even more dangerously susceptible to manipulation by war-seeking advisers, particularly the Poloniesque William Gascoigne (Sean Harris), who manufactures conspiracies against Henry to be blamed on France and expendable colleagues. It doesn't help matters that the French Dauphin (Robert Pattinson in a critic-proof performance as a complete idiot) wants to get into some kind of pissing contest with the new king, or at least wants to fart in his general direction. Falstaff and later the French princess Catherine (Lily-Rose Depp) act as Henry's conscience against the tide of war, constantly questioning the need for war and reinforcing his own instinctual skepticism, born of resentment of the belligerent ways of his father (Ben Mendelsohn). Henry's the type who prefers to settle things by single combat when possible, as he does with the archetypal Hotspur rather than see his own brother waste an army and his own life in a pointless battle. A nice touch in this film is the way it shows Henry becoming Hotspur, i.e. the son his father really wanted despite Hotspur's treason. Another touch is the way that character arc ends with a parody of the early Hotspur fight, as the Dauphin challenges Henry to single combat after the big battle -- Michôd acquits himself fairly well in the shadow of past auteurs, by the way, and Chalamet works hard in long, violent takes -- but can't put one armored foot in front of the other without sprawling into the mud. The film ends with Catherine replacing Falstaff as Henry's good conscience and his evil counselors done away with all too neatly. But while it's all too obvious when actors are mouthpieces for the writers' opinions rather than real characters, and the film is absolutely not to be taken seriously as history, The King is a nicely made piece of work and mostly quite entertaining, especially if you're a sucker for historical epics like I am. It's just too bad that as a self-conscious alternative to the Shakespearean "Henriad," it's doomed to comparison with greater films instead of facing judgment on its own terms.

Sunday, January 12, 2020

Happy New Year: 1917 (2019)

So what happened? Nothing, really -- if anyone was wondering. There was just a period where I didn't watch much worth writing about, or else I found myself having nothing I thought worth writing about the things I saw. The turn of the year usually encourages increased productivity, however, and by then I had seen some things I wanted to write about. It then became a matter of resuming the old habit. Finally getting back to a movie theater after a few months provided the occasion, and from here I'll backtrack a little to cover some stuff I saw less recently. Where better to start, though, then more than a century in the past?...

Now that history has taken World War I beyond living memory, it finally starts to feel like just another war. For a time, it seemed like it actually might be the war to end all war, because it seemed to be the one that discredited war as a concept. It stood for futility and tragic stupidity, an indictment of leaders military and political alike. But the most recent Great War movies -- at least in English -- have been far less bitter about the conflict than the classic familiar takes on the subject. Peter Jackson's documentary They Shall Not Grow Old and Sam Mendes' new film are inspired by ancestral memories on the grunt level, where the war was perceived, so it seems, as just another job of work. There is little in either film of the indignation characteristic of Great War movies going back at least to All Quiet on the Western Front and at least as far forward as Gallipoli. In fact, 1917 is to some extent Gallipoli with a happy ending. If that exaggerates things slightly, it's still fair to say that neither the Mendes nor the Jackson film is explicitly an antiwar film, as nearly all World War I movies were implicitly for a long time. Saying this isn't an indictment, only an observation of a change in tone that comes with a change in perspective.

It may exaggerate things even more to call 1917 World War I as a video game. It certainly will look that way to some people, but the effort by Mendes and cinematographer Roger Deakins to make their film look like a handful of long takes -- however obvious the cutting points actually are -- really seems rooted in an engagement with past war films. All Quiet remains arguably the most indelible of Great War films because of Lewis Milestone's epic horizontal tracking shots of advancing troops mowed down by machine gun fire, while Stanley Kubrick's Paths of Glory is well remembered for its lengthy tracking shots in the trenches and on the battlefield. 1917 may not be so much an attempt to top these films but a resort to a common cinematic language that somehow seems suited to the subject. Film buffs associate that war in particular with long takes and tracking shots, so if Mendes was going to make a film about that war, this was the way to make it feel especially like a World War I movie -- at least superficially.

Watching 1917, I had the obscure thought that Mendes and Deakins would have been ideal adapters of the work of Leonard H. Nason, an unsung author whose 1920s pulp stories of American soldiers blundering their way across the western front capture something of the chaos of war with considerable black or at least hard-boiled comedy. Instead, of course, Mendes and co-writer Krysty Winston-Cairns took inspiration from tales told by Mendes' grandfather. Whether grandpa told the future director a tale with a Private Ryan-style "mission is a man" hook, however, I don't know. The idea is that two soldiers (Dean-Charles Chapman and George McKay) must traverse dangerous terrain on foot in order to prevent a sure-to-fail attack that will jeopardize the life of the brother of one of the protagonists. Their journey inevitably is full of incidents, and as I hinted earlier, their mission ultimately is a success by the narrowest of margins. Your archetypal World War I movie probably would have ended differently, but 1917 plays out, to mix historical metaphors, like an Apocalypse Now that finds the colonel at the end of the long trail a surprisingly reasonable man. Crossing historic boundaries to make that comparison feels justified because 1917 is as much a tour de force for Deakins as the Coppola film was for Vittorio Storaro. The beloved cinematographer not only gives you your standard Great War mudscape, but also a wide range of settings permitting a more vivid and sometimes lurid palette of colors than we might expect from the archetypically monochrome imagery of that conflict. Whatever you think about the story -- which comes with a twist or two and may actually depend on our expectations for Great War films to maintain suspense -- 1917 is a treat to look at, as long as your definition of "treat" includes lots of moldering corpses. The horrors of war are plainly there to see, but at this point in movie history Mendes feels little need to editorialize over them. That certainly doesn't make this a pro-war film, but longtime movie fans will feel a difference from earlier Great War pictures, whatever they make of it. 1917 feels more like an exercise in style for its own sake, both because of its stunt quality and because the characters aren't really that interesting, than its famous precursors, but I think it'll be safe to say that it won't make anyone wish they could have their own World War I adventure, except perhaps in the comfort of their game room.

* * *

Now that history has taken World War I beyond living memory, it finally starts to feel like just another war. For a time, it seemed like it actually might be the war to end all war, because it seemed to be the one that discredited war as a concept. It stood for futility and tragic stupidity, an indictment of leaders military and political alike. But the most recent Great War movies -- at least in English -- have been far less bitter about the conflict than the classic familiar takes on the subject. Peter Jackson's documentary They Shall Not Grow Old and Sam Mendes' new film are inspired by ancestral memories on the grunt level, where the war was perceived, so it seems, as just another job of work. There is little in either film of the indignation characteristic of Great War movies going back at least to All Quiet on the Western Front and at least as far forward as Gallipoli. In fact, 1917 is to some extent Gallipoli with a happy ending. If that exaggerates things slightly, it's still fair to say that neither the Mendes nor the Jackson film is explicitly an antiwar film, as nearly all World War I movies were implicitly for a long time. Saying this isn't an indictment, only an observation of a change in tone that comes with a change in perspective.

It may exaggerate things even more to call 1917 World War I as a video game. It certainly will look that way to some people, but the effort by Mendes and cinematographer Roger Deakins to make their film look like a handful of long takes -- however obvious the cutting points actually are -- really seems rooted in an engagement with past war films. All Quiet remains arguably the most indelible of Great War films because of Lewis Milestone's epic horizontal tracking shots of advancing troops mowed down by machine gun fire, while Stanley Kubrick's Paths of Glory is well remembered for its lengthy tracking shots in the trenches and on the battlefield. 1917 may not be so much an attempt to top these films but a resort to a common cinematic language that somehow seems suited to the subject. Film buffs associate that war in particular with long takes and tracking shots, so if Mendes was going to make a film about that war, this was the way to make it feel especially like a World War I movie -- at least superficially.

Watching 1917, I had the obscure thought that Mendes and Deakins would have been ideal adapters of the work of Leonard H. Nason, an unsung author whose 1920s pulp stories of American soldiers blundering their way across the western front capture something of the chaos of war with considerable black or at least hard-boiled comedy. Instead, of course, Mendes and co-writer Krysty Winston-Cairns took inspiration from tales told by Mendes' grandfather. Whether grandpa told the future director a tale with a Private Ryan-style "mission is a man" hook, however, I don't know. The idea is that two soldiers (Dean-Charles Chapman and George McKay) must traverse dangerous terrain on foot in order to prevent a sure-to-fail attack that will jeopardize the life of the brother of one of the protagonists. Their journey inevitably is full of incidents, and as I hinted earlier, their mission ultimately is a success by the narrowest of margins. Your archetypal World War I movie probably would have ended differently, but 1917 plays out, to mix historical metaphors, like an Apocalypse Now that finds the colonel at the end of the long trail a surprisingly reasonable man. Crossing historic boundaries to make that comparison feels justified because 1917 is as much a tour de force for Deakins as the Coppola film was for Vittorio Storaro. The beloved cinematographer not only gives you your standard Great War mudscape, but also a wide range of settings permitting a more vivid and sometimes lurid palette of colors than we might expect from the archetypically monochrome imagery of that conflict. Whatever you think about the story -- which comes with a twist or two and may actually depend on our expectations for Great War films to maintain suspense -- 1917 is a treat to look at, as long as your definition of "treat" includes lots of moldering corpses. The horrors of war are plainly there to see, but at this point in movie history Mendes feels little need to editorialize over them. That certainly doesn't make this a pro-war film, but longtime movie fans will feel a difference from earlier Great War pictures, whatever they make of it. 1917 feels more like an exercise in style for its own sake, both because of its stunt quality and because the characters aren't really that interesting, than its famous precursors, but I think it'll be safe to say that it won't make anyone wish they could have their own World War I adventure, except perhaps in the comfort of their game room.