Nicolas Winding Refn may have been better off putting his dedication to Alexandro Jodorowsky at the start of his latest picture. Then reviewers might have known what they were getting into and wouldn't blame the director for disappointing unwarranted expectations. But like his protagonist, Refn may have wanted to be punished, and in any event the director of El Topo and Santa Sangre is just one of the influences running rampant in Refn's imagination. Only God Forgives is a volatile synthesis of all Refn's influences, a riot of archetypes, and at the same time some sort of self-criticism, if not also a preemptive rebuke to an audience that had but recently embraced him only to repudiate him once he failed to offer them another (cue heavy sarcasm) gritty slice of verisimilitude like Drive. It was one thing to pay homage to or pretend to be Michael Mann in the last picture, and too many things more this time for the mainstream audience to bear.

Nicolas Winding Refn may have been better off putting his dedication to Alexandro Jodorowsky at the start of his latest picture. Then reviewers might have known what they were getting into and wouldn't blame the director for disappointing unwarranted expectations. But like his protagonist, Refn may have wanted to be punished, and in any event the director of El Topo and Santa Sangre is just one of the influences running rampant in Refn's imagination. Only God Forgives is a volatile synthesis of all Refn's influences, a riot of archetypes, and at the same time some sort of self-criticism, if not also a preemptive rebuke to an audience that had but recently embraced him only to repudiate him once he failed to offer them another (cue heavy sarcasm) gritty slice of verisimilitude like Drive. It was one thing to pay homage to or pretend to be Michael Mann in the last picture, and too many things more this time for the mainstream audience to bear.Only God Forgives is the story of a man who doesn't want to play his archetypal role. Julian (Ryan Gosling, returning from Drive) is an American fight promoter and drug dealer operating in Thailand with his brother. Both brothers are odd characters. Julian sees a prostitute and has her bind his hands to a chair so he can only watch while she masturbates. His brother raises a ruckus in a brothel when it can't provide a 14 year old girl for him; finding one later from an independent contractor, he rapes and kills her. Enter a plainclothes policeman, Chang (Vithaya Pansringarm), who takes the brother prisoner, then basically orders the victim's father to beat the American to death. Then Chang chops the father's arm off with a machete he keeps in a sheath under the back of his shirt; this is punishment for prostituting his daughter and a warning not to do that with his other daughters.

Already tormented by inner demons -- he has a premonition of Chang chopping his arm off, possibly before he's ever met the man -- Julian is now tormented by his fury of a mother, Crystal, (Kristin Scott Thomas), who demands that Julian avenge his brother's death. Not taking no for an answer -- Julian knows what his brother did but Mom assumes that her boy "had his reasons" -- the mother hires hit squads on her own to kill Chang. The hitmen shoot up a noodle shop but miss their target, who seems to live a charmed life. As Chang follows the trail back to the source, Mom increases the pressure on Julian to protect her or raise the stakes for Chang. Julian has the childish notion that things might be settled by unarmed combat ("You wanna fight?") between himself and Chang but the policeman kicks his ass Muy Thai style. Now Julian is motivated enough by the growing threat to his mom, and perhaps by the humiliation he endured at Chang's hands and feet, to agree to a plot to ambush the cop at his home. But he draws the line, a little too late actually, at killing Chang's family.Chang has no such scruples, but then again, Julian's family is guilty. So's Julian himself, if we can believe a story that seems to explain his mania to restrain his hands, but at least he has a guilty conscience, for all the good it does him.

If this film's fantasies of dismemberment put Refn in Jodorowsky's debt, it's hard to believe there's no similar debt to Tod Browning, the cinematic pioneer of dismemberment fantasies in weird settings. But I could be here all night listing all the sources of Refn's fantasia. Many reviewers focused on David Lynch because of the prominence of karaoke in the picture and the sheer weirdness of Chang having it for a hobby. I thought the karaoke scenes helped demonstrate how much of a self-dramatizing personality Chang is, as much if not more so than his ultimate antagonist, Julian's flamboyant diva of a mother. Chang is determined to stage-manage reality, from his certainly unauthorized on-the-spot punishments to his compelling the dead girl's father to do justice's dirty work on Julian's brother. One gets the feeling that his cop stooges are a captive if sycophantic audience for Chang's musical performances. Likewise, Crystal wants Julian to play a role in her personal drama of vengeance, striving to define him to other people, whether she's telling his Thai girlfriend about his sordid business (and belittling his manhood compared to his brother) or warning Chang that Julian beat his own father to death with his bare hands. For his part, Julian is willing to play the role of the dutiful son -- rebuking his girlfriend angrily when she questions her verbal abuse of him and excusing it with "Because she's my mother" -- so long as it contributes to the penance to which he's subjected himself. On some level Julian has renounced violence yet lives in a milieu where violence will be inevitable and the line he draws for himself matters little to anyone else. On another, he represents the folly of a violent movie passing itself off as a critique of violence.

Most reviewers saw Julian's issues as part of what they saw as the film's pretentiously derivative yet ultimately senseless weirdness. Many went further and accused Refn of racism, mistaking his portrait of an underworld that has Americans and other foreigners at its center for a caricature of Thailand as a whole. But Chang is the sort of avenging rogue cop that could turn up anywhere, rendered exotic only by his choice of weapon and his karaoke hobby. But I suppose that if I can credit Only God Forgives for its effort to be all-encompassing of Refn's influences, others might feel that the film is guilty of all possible sins. Refn's principal sin, of course, was his failure to meet a Hollywood standard of realism after passing that test with Drive. Instead, Only God Forgives is this year's brightest triumph of style as substance, from the lurid cinematography of Larry Smith to Cliff Martinez's menacing score, the best I've heard so far this year. It's all simultaneously alienating and alluring. While many see their disgust at it as proof of good taste, others will regard their own admiration as a mark of distinction. Ryan Gosling deserves a lot of credit for sticking with Refn for this picture, and for giving an eloquently minimal performance, but the real test of his courage will be if he works with Refn again. He deserves our encouragement.

T

T I

I D

D

A

A

P

P A

A

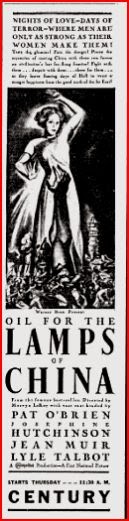

Warners did O'Brien no favor by casting him as Stephen Chase. Sure, it was a high-profile part based on a best-seller, but Chase hardly cuts a heroic figure here. It doesn't help that the studio apparently couldn't afford to show him fighting that oil fire. His battle to save a village is treated the way his wife sees it, as an unworthy distraction from the birth of his baby. A viewer might side with him awhile after everyone guilt-trips him, but it's hard to keep liking him when he never, ever wises up. He may be some sort of China expert -- though the film suggests that his expertise is growing obsolete -- but his real problem is that he can't understand the corporate culture in which he's embedded. At least he doesn't understand it as novelist Hobart (who based her writing partially on life experience) and adapter Laird Doyle see it. While O'Brien flounders, LeRoy does everything possible to tell the audience that the Oil movie is telling a lot less than the novel does. Perhaps the worst possible thing you could do while filming a literary adaptation is to use shots of flipping pages of the actual book as a transition device. Nothing you could do would say more clearly, "There's a lot of story here that we're just going to skip." Just about all literary adaptations skip a lot of story, or at least a lot of detail, but few are as guileless about admitting it as this one. It's not an endearing quality. Personally, I was hoping for something more pulpy, more self-consciously exotic -- something that hinted at what America was really thinking when it thought about China. Instead, Oil For the Lamps of China is a domesticated if not domestic melodrama that reduces the exploitation of an ancient empire to the dull ordeal of an organization man. For all I know it was faithful to the novel, but as a movie it's a big disappointment.

Warners did O'Brien no favor by casting him as Stephen Chase. Sure, it was a high-profile part based on a best-seller, but Chase hardly cuts a heroic figure here. It doesn't help that the studio apparently couldn't afford to show him fighting that oil fire. His battle to save a village is treated the way his wife sees it, as an unworthy distraction from the birth of his baby. A viewer might side with him awhile after everyone guilt-trips him, but it's hard to keep liking him when he never, ever wises up. He may be some sort of China expert -- though the film suggests that his expertise is growing obsolete -- but his real problem is that he can't understand the corporate culture in which he's embedded. At least he doesn't understand it as novelist Hobart (who based her writing partially on life experience) and adapter Laird Doyle see it. While O'Brien flounders, LeRoy does everything possible to tell the audience that the Oil movie is telling a lot less than the novel does. Perhaps the worst possible thing you could do while filming a literary adaptation is to use shots of flipping pages of the actual book as a transition device. Nothing you could do would say more clearly, "There's a lot of story here that we're just going to skip." Just about all literary adaptations skip a lot of story, or at least a lot of detail, but few are as guileless about admitting it as this one. It's not an endearing quality. Personally, I was hoping for something more pulpy, more self-consciously exotic -- something that hinted at what America was really thinking when it thought about China. Instead, Oil For the Lamps of China is a domesticated if not domestic melodrama that reduces the exploitation of an ancient empire to the dull ordeal of an organization man. For all I know it was faithful to the novel, but as a movie it's a big disappointment.

Why, it's Jean-Pierre Melville, the French master of crime and suspense, the direcor of Le Samourai and Army of Shadows. Don't let his sleepy demeanor deceive you; he's a busy man today. Melville isn't just writing and directing this picture, but he's acting as well -- in fact, though he doesn't take top billing, Monsieur Modest is the main character of the story. And he shares a cinematography credit with Nicolas Heyer. He's in New York to shoot exteriors (and the interior of a subway train) and establish atmosphere; he'll shoot the other interiors back home in France. They don't really match that well, but Melville's Manhattan is less a physical place than a territory of mood and music. His opening credits play over Times Square to establish his bona fides, but his camera sets the tone by pulling inexorably away from the familiar crossroads of the world toward darker, more nondescript places. The music still says Manhattan, however, if not America, or 1959. Some of it sounds like library music but much of it is jazzily evocative the way Melville intended. This French film could be the soundtrack for a certain strata of America at the end of the Fifties, where rock 'n roll hasn't reached yet, where the tone of the vibraphone is the church bell of sophistication ringing through the midnight fog cigarette smoke across a sea of booze. They call this film an homage to film noir but it's more of a homage to its own time than to the decade past. It's a Fifties, not a Forties film, in spirit as well as fact.

Why, it's Jean-Pierre Melville, the French master of crime and suspense, the direcor of Le Samourai and Army of Shadows. Don't let his sleepy demeanor deceive you; he's a busy man today. Melville isn't just writing and directing this picture, but he's acting as well -- in fact, though he doesn't take top billing, Monsieur Modest is the main character of the story. And he shares a cinematography credit with Nicolas Heyer. He's in New York to shoot exteriors (and the interior of a subway train) and establish atmosphere; he'll shoot the other interiors back home in France. They don't really match that well, but Melville's Manhattan is less a physical place than a territory of mood and music. His opening credits play over Times Square to establish his bona fides, but his camera sets the tone by pulling inexorably away from the familiar crossroads of the world toward darker, more nondescript places. The music still says Manhattan, however, if not America, or 1959. Some of it sounds like library music but much of it is jazzily evocative the way Melville intended. This French film could be the soundtrack for a certain strata of America at the end of the Fifties, where rock 'n roll hasn't reached yet, where the tone of the vibraphone is the church bell of sophistication ringing through the midnight fog cigarette smoke across a sea of booze. They call this film an homage to film noir but it's more of a homage to its own time than to the decade past. It's a Fifties, not a Forties film, in spirit as well as fact.

T

T O

O