The title sequence is an allegory of the pirate's race with death. We see an elaborate faux-ivory figurehead detailed with scenes of seamanship, love, violence and skeletons. The sequence closes with a skeleton army charging a pirate army while a skeleton races a pirate up a mast to seize a flag. This skeleton business is Black Sails' sole concession to the Pirates of the Caribbean audience, while the show itself proves decisively that a pirate tale doesn't need those films' fantastic trappings to hold an audience.

Created by Jonathan E. Steinberg and Robert Levine and bankrolled by Michael Bay in a way that redeems a lot in his past, Black Sails combines two dominant pop-culture tropes: the revisionist fairy tale and the prequel. Robert Louis Stevenson might object to his novel Treasure Island being called a fairy tale, but as a canonical "children's story" it's just about that. Stevenson's Long John Silver was the archetypal pirate for generations; as interpreted on film by Wallace Beery and Robert Newton, he's arrrrrh image and voice of piracy to this day. Black Sails' initial hook is its promise of an "origin" story for Silver. Its Silver (Luke Arnold) is a handsome, healthy, clever and charismatic young schemer, at least a generation younger than the one-legged 50 year old Long John of the novel. If the payoff of other prequel shows presumably is a hero putting on his costume or simply beginning his career, the presumed payoff of Black Sails was Silver losing his leg, and it came last weekend during the finale for the second season, with a third already in production. I read through Treasure Island last week to prepare for this review, however, and the story of Silver's amputation on TV differs from what the character tells Jim Hawkins in the novel. In the book Long John says he lost the leg to a broadside during a sea battle. On TV the leg is amputated after it was broken during torture as Silver resists condemning most of his shipmates to death. This is not poor memory or scholarship on the writers' part but their further establishing that Black Sails is really an alternate reality from that of Stevenson's story.

The genius of the show is its mashup of Stevenson's characters, historical pirates, and original characters. Along with Silver, the first group includes Billy Bones (Tom Hopper), later the drunken, dying seaman of Treasure Island's opening chapters and, most importantly, the infamous Captain Flint (Toby Stephens), the show's real main character, who is long dead by the time the novel begins. The historical characters include the pirate captains Charles Vane (Zach McGowan) and Jack Rackham (Toby Schmitz) and Rackham's more famous protege Anne Bonny (Clara Paget). The original characters include Eleanor Guthrie (Hannah New), who controls trade (i.e. fencing) in the pirate stronghold of Nassau; her former lover Max (Jessica Parker Kennedy), a favored prostitute turned rival; and Miranda Barlow (Louise Barnes), an upper-class woman whose influence over Flint is a first-season mystery resolved through flashbacks during the second season. Of this last group, Max may cross into another category; because she's a "woman of color," many Treasure Island readers expect that she'll end up as the novel's unseen, business-savvy wife of John Silver the Bristol tavern keeper. Another theory is that she may end up in the historical category; currently involved in a menage-a-trois with Rackham and Bonny, she might take up the role of their real-life cross-dressing cohort Mary Read. This volatility is part of the fun of the show. The mix of real, canonical and original characters means that Black Sails needn't be bound by history or literature.

That being said, the main storyline for the first two seasons has been the pursuit of what we presume to be the treasure of the novel's island. On the show it's the gold of the Spanish treasure galleon Urca de Lima, the shipwreck of which is based loosely on real events. While the race for the loot occasionally returns to the forefront, it's often little more than a MacGuffin in the background of the main action: the threeway rivalry, to put it at a minimum, of Flint, Vane and Guthrie for dominance in Nassau, and the shared struggle to keep Nassau effectively independent of British control. Each of the three main players, meanwhile, must struggle to keep his or her own house in order. As Stevenson knew, the pirate world was a kind of democracy, and often a messy kind that required leaders to be both forceful and flexible to maintain the loyalty of their crews. Much of the first season was taken up with the negotiation of a personal alliance of Flint and Silver (Flint's quartermaster in the novel's backstory) on which Flint's continued captaincy depended. By now Vane has fallen and risen again a few times over, while Eleanor Guthrie has been toppled from her perch, with only a third-season promo clip as proof that she'll even remain on the show, creating a vacuum for Max to take over. Guthrie has taken Flint's or Vane's side as it's suited her interests, and the two captains have gone from fighting to the death to Vane rescuing Flint from execution in last weekend's episode, after Vane's men had seized Flint's ship by force and clapped Flint's crew in irons. Alliances shift like the winds on this show, and while not every shift is equally convincing, the adaptability required of the pirates and their facilitators is plausible enough.

Black Sails works on several levels at once. It's one of the best action shows on TV, with the last episode's escape of Flint and Vane from a Charleston deathtrap and the pirates' destruction of the Carolina city the latest proof. It'll also satisfy anyone's appetite for intrigue, as almost all the characters, even the most barbaric like Vane, maneuver with pragmatic intelligence. It passes another crucial test for modern TV by being one of the shows that Goes There, and being a premium-cable show, it can go further out than broadcast of basic-cable shows. If there's a CW stereotype, there's also a Starz stereotype (established by the channel's Spartacus series) of nudity, extreme violence and f-bombs in ancient settings (see also Da Vinci's Demons). Black Sails transcends the stereotype with a tragic sensibility. Flint, the monster of legend in Treasure Island, here has a utopian dream of Nassau as a truly free country whose outcast citizenry can pursue their dreams without answering to King or Parliament. By the end of the second season that dream has been dashed several times over, apparently setting the stage for Flint's devolution to legendary evil (if not also the legendary dissipation described in the novel). There's a broader romantic utopianism to modern perceptions of the pirate age that idealizes not only the democracy of crews but also a more liberal sexuality and a most-likely overrated blurring of gender roles. Black Sails caters to this in its several storylines of female empowerment, from Eleanor's struggles to shrug off her father's influence to Max's rise from the lowest levels of prostitution to Anne Bonny's fight to define herself as something more than a vicious appendage to Jack Rackham. It's probably no accident that all three characters are bisexual, but it's more daring of the show to make Flint bi as well, even if Da Vinci's Demons had been there already. Even in Stevenson's time, for all that he portrays all pirates but Silver as hopeless drunks, the fantasy of piracy was a dream of freedom, but even as Black Sails indulges that dream it's ever mindful of the inexorable shadow of empire lengthening toward Nassau, while foreknowledge of Treasure Island only enhances the sense that everything we see is doomed.

A rich ensemble of actors puts it all over. The nearest thing to a weak link is Hannah New as Guthrie, if only because the writers often try to hard to make a badass out of her with cuss words when she can't be a warrior badass like Anne. When you're not tempted to start a drinking game around her f-bombs New is actually pretty good. As Silver, Luke Arnold lives up to the Treasure Island pirates' memory of the young Long John as an articulate, charismatic mastermind. As Flint, Toby Stephens retains an air of mystery (along with the tragedy) over the course of a slow burn, though most of the why of the captain's reputed career of atrocity has been established by now. For me, the most impressive cast member is Zach McGowan, who manages with his eyes and gestures and sheer animal physicality a near-miraculous feat of investing Charles Vane with compelling personality despite an almost totally inexpressive face and voice. I was stunned to learn that Vane had never been a character in a pirate movie before, while Blackbeard and Kidd and Morgan had been done time and time again. This histories I've been reading while watching the show give Vane, Rackham et al an epic quality that Black Sails more than lives up to. The visuals live up to the acting, with the latest episode hitting a new peak with a panoramic climax: a dying villain watches helplessly, as if witnessing the wrath of God, as his dream falls to pieces all around him, while his violated victim, a corpse abused by a mob, appears to look on damningly. That's the best thing I've seen on TV so far this season, and for now Black Sails is the best show I watch.

A randomly comprehensive survey of extraordinary movie experiences from the art house to the grindhouse, featuring the good, the bad, the ugly, but not the boring or the banal.

Monday, March 30, 2015

Saturday, March 28, 2015

On the Big Screen: TIMBUKTU (2014)

Here is a film that might make you want to punch a Muslim, except that its subject is the oppression by Muslims of Muslims, and the director, Abderrahman Sissako, is Muslim himself. What we have instead is what Islamophobes have clamored for: a denunciation by a Muslim of the excesses of Islamism. Timbuktu might end up disappointing hard-core Islamophobes, however, since Sissako makes it fairly clear that those excesses are fueled by selective, self-serving readings of Islamic scripture rather than by something essential to Islam itself. Sissako is also wise enough to remember that Islamism is not an intrusion on otherwise peaceful, innocent communities, since one of the central conflicts in his story has nothing to do with religion or anyone's interpretation of it. Most importantly, he's enough of an artist as a director to make his story pictorially memorable, assuring it of a lasting impact.

Here is a film that might make you want to punch a Muslim, except that its subject is the oppression by Muslims of Muslims, and the director, Abderrahman Sissako, is Muslim himself. What we have instead is what Islamophobes have clamored for: a denunciation by a Muslim of the excesses of Islamism. Timbuktu might end up disappointing hard-core Islamophobes, however, since Sissako makes it fairly clear that those excesses are fueled by selective, self-serving readings of Islamic scripture rather than by something essential to Islam itself. Sissako is also wise enough to remember that Islamism is not an intrusion on otherwise peaceful, innocent communities, since one of the central conflicts in his story has nothing to do with religion or anyone's interpretation of it. Most importantly, he's enough of an artist as a director to make his story pictorially memorable, assuring it of a lasting impact.Sissako is Mauritanian but his subject is Mali, where the title city is located. In Timbuktu the 21st century exists alongside timeless folkways. Satellite dishes crown the roofs of mud-brick buildings of perhaps incalculable age; nomads communicate with cellphones; a favorite cow is named GPS. To this place the jihadis came with all their absurd chickenshit laws, announced with megaphones in as many languages as the intruders know. Many of the occupiers don't know the local languages, making interpreters essential while highlighting a mutual incomprehension that a common faith can't overcome. In one case a commander requires an underling to inform him in English of what he sees at a crime scene. Yet these strangers claim a religious entitlement to tell the natives how to live. Women have to wear socks and gloves in the marketplace. The idea is so ridiculous and insulting to one of the female fishmongers ("We were brought up in honor and didn't have to wear gloves!") that she's willing to be arrested because she's sick and tired of the jihadi bullshit. Soccer and all sports are banned, even though some of the jihadis are football fans. One moment of comic relief comes when we overhear them talking about how many times somebody won or lost in the last few years. Almost certainly an unspoiled audience will assume they're talking about armies in war, but they're really debating the superiority of French and Spanish soccer teams. A fan of Spain accuses the French of bribing Brazil to throw the 1998 World Cup final; I wonder how he'd explain last year's semifinal. In any event, after a ball is confiscated, local sportsmen console themselves with a pantomime game, though when the hardcore jihadis ride by they revert to innocent calisthenics. Music is also forbidden by these totalitarian puritans, though one of them questions whether they should break in on someone singing praises to God. There's less hesitation when they find a mixed gathering with a woman singing secular lyrics while a man plays guitar. For this they're flogged, the woman defiantly singing the same song until the pain is too great. At least they didn't commit adultery. The penalty for that is stoning, and the jihadis ain't playing. No ducking or dodging for the guilty here; they're buried up to their necks and the rest is just target practice.

From a distance, from his tent, the herdsman Kidane (Ibrahim Ahmed dit Pinto) watches with concern as his nomad neighbors start to move away. He wants to stay, however, even though a jihadi commander is making suspicious visits to his wife and daughter when he's away. He's more concerned with Amadou, a cranky fisherman (who wears western clothes, for what that's worth) who begrudges Kidane's cattle drinking at the lake because he's afraid they'll foul his nets. His fears aren't unfounded, and when the beloved GPS wanders into his nets he kills the cow with a spear. Little does Amadou realize that he's brought a spear to a gunfight, though from all appearances the weapon Kidane brings to their confrontation goes off accidentally during their damp scuffle. Their conflict has had nothing to do with jihad until now, when the jihadis have to act as judges in the case. They set a blood money fine (in kind) that's more than Kidane is able or willing to pay. All that leaves to be decided is whether he'll see his family one more time....

Timbuktu is a photogenic location -- some of the architecture will remind movie buffs of Ousmane Sembene's classic Moolaade -- and Sissako films his story is a classically artful style. He makes brilliant use of the widescreen frame in a way that can only be appreciated on the big screen. Kidane has crossed a shallow lake to confront Amadou. After the gun goes off, he lays in the water awhile in shock, then springs back to life to assure himself that he is alive. Sissako cuts to a wide shot that encompasses both shores as Kidane staggers back to his side. We might almost miss Amadou stirring and lurching upright in the other direction. From this godlike distance we see Amadou struggle for the shore and fail as Kidane plows ahead without a look back. The moment has some of the same cold grandeur of the drowning scene in Under the Skin. At other points you wonder whether Sissako is quoting other filmmakers. The opening scene of jihadis in a jeep chasing a deer, opening with the deer, might remind you of Ran or Hatari!, while genre fans, at least, are tempted to see any shot of a ball bouncing ominously as an homage to Mario Bava's Kill Baby Kill. The director is enough his own man, however, that none of this looks fannish or blatant.

During that opening scene, one of the jihadi deer hunters tells the others not to shoot, but to tire the animal. If there's anything blatant about the scene, it's not any embedded homage but the thematic premonition. Apart from Kidane's storyline, Timbuktu is mainly about the wearing down of resistance through relentless petty regulation. That angry fishmonger ends up wearing gloves after all, and no one really scores a victory over the jihadis except the local madwoman, whose apparent immunity to the new dress code seems to confirm the old pulp chestnut about Muslims fearing to harm the insane.Then again, selectivity and hypocrisy characterize these jihadis. Practically the first order we hear is that smoking is forbidden, yet one of the leaders, the man paying suspicious attention to Kidane's wife, while needing an interpreter to talk to her, goes into the desert to sneak a few drags, only to be told by his driver that everyone knows of his habit, but no one apparently cares. The most damning case of selective rules involves an Anglophone jihadi (Nigerian, I presume?) courting a local girl. The girl's mother turns him down because she barely knows the man, despite his warning that he'll take the girl "in a bad way." The next day, we learn that he grabbed the girl and had his commander marry them. When a local qadi (for want of a more accurate term) protests, the commander first asks why anyone would complain about getting the guy for a son-in-law ("He's perfect!"), then quotes scripture commanding that righteous fighters like this guy should be given brides. One gets a feeling the qadi knows Islam better than the commander does, but the man with the power decides what religion requires. These jihadis claim to be all about religion, but Sissako seems to know better. People who wonder what's the matter with Islam probably should take his word for it. Timbuktu may not be the best of last year's Oscar nominees for Best Foreign Film -- it lost to Ida here while sweeping the year's French film awards -- but it would have deserved to win if a win meant more Americans would see it. If any 2014 film needs to be seen by more people, this may be it.

Tuesday, March 24, 2015

MARDAANI (2014): "This is India!"

While bigots get beaten down for comedy relief, Mardaani taps something darker in Indian society at its climax. Shivani has defeated Walt and in the process has exposed a powerful politician whose kink is raping prostitutes. She has challenged Walt to hand-to-hand combat, as mentioned above, and humiliated him. But he doesn't care and isn't worried. "This is India," he reminds her, and that means his political and business connections will see to it that he serves little if any time. Her answer? Yes, this is India, but that means she doesn't necessarily have to arrest him to get him off the streets. Is she going to murder him, then? No, but they are: the girls he's tortured and exploited. Technically it won't be murder. Since this is India, the law there says it isn't murder is someone is killed in a demonstration involving a certain number of people or more. There just happens to be a quorum present, so as Shivani discreetly walks away the film's upbeat girl-power theme song plays over a lynching, the death of a thousand kicks from high-heeled shoes.

Mardaani's over-the-top final act alone makes the film worth seeing for fans of global pop cinema. Mukerji brings badass authority to her lead performance, and that's all the film really needs. I haven't watched as much Indian cinema as I probably should have by now, so I don't know how extraordinary or transgressive such a female role would be there. But it certainly can't hurt anywhere for people to see women kicking ass on the big screen. Just maybe it might make some men think twice before acting out their fantasies.

Monday, March 23, 2015

That's all I'm taking from you....

Gregory Walcott died last weekend at the age of 87. He reached the height of his career in the 1970s with a solid run of character-actor parts, particularly in films by Clint Eastwood but also in Steven Spielberg's Sugarland Express. As far as I know Walcott was the only man to be directed by both Spielberg and Ed Wood -- and he acted in Tim Burton's Ed Wood biopic as well -- but we all know what he'll be remembered for. He was the rare actor who crossed paths with Wood on his way up and that early work for the World's Worst Director might have been forgotten amid a solid Seventies filmography had not Wood and Plan 9 From Outer Space been elevated from obscurity at the end of the decade, after Wood's own death. Anyway, here's that blast from the past as uploaded to YouTube by docretro9000, and it really is a special moment.

Sometimes you feel like Dudley Manlove's Eros is speaking for you, as only he could, and sometimes you want to answer the whole smug judgmental world the way Walcott does. Maybe it is true that because of his stupidity, all must be destroyed, but if Plan 9 teaches us anything, it's that everyone is stupid, including those who judge us, and that those who judge will be judged in turn. Manlove and Walcott are two sides of the same coin, and all you can buy with it is self-destruction. Whatever side he's on, Gregory Walcott will keep on fighting.

Sometimes you feel like Dudley Manlove's Eros is speaking for you, as only he could, and sometimes you want to answer the whole smug judgmental world the way Walcott does. Maybe it is true that because of his stupidity, all must be destroyed, but if Plan 9 teaches us anything, it's that everyone is stupid, including those who judge us, and that those who judge will be judged in turn. Manlove and Walcott are two sides of the same coin, and all you can buy with it is self-destruction. Whatever side he's on, Gregory Walcott will keep on fighting.

Sunday, March 22, 2015

DVR Diary: LADY WITH A SWORD (Feng Fei Fei, 1971)

Kao Pao Shu was a veteran Shaw Bros. actress who moved behind the camera to make her directorial debut with Feng Fei Fei. So is it because she was a woman that this is one of the more tearjerking martial arts pictures? Hard to say, since a man, the prolific I Kuang, wrote the screenplay. But I still wonder whether the prevailing unhappiness of the picture reflects a feminine touch. Lots of martial arts films end unhappily, but usually that's because all the characters are dead. There are plenty of survivors at the end of Lady With a Sword, by comparison, but they're all very unhappy. It's hard to blame them, though.

Kao Pao Shu was a veteran Shaw Bros. actress who moved behind the camera to make her directorial debut with Feng Fei Fei. So is it because she was a woman that this is one of the more tearjerking martial arts pictures? Hard to say, since a man, the prolific I Kuang, wrote the screenplay. But I still wonder whether the prevailing unhappiness of the picture reflects a feminine touch. Lots of martial arts films end unhappily, but usually that's because all the characters are dead. There are plenty of survivors at the end of Lady With a Sword, by comparison, but they're all very unhappy. It's hard to blame them, though.I wonder whether writer or director saw the American western Last Train From Gun Hill. In that picture Kirk Douglas destroys his old friendship with Anthony Quinn because he, a lawman, has to take Quinn's son to prison. Feng Fei Fei escalates the emotional stakes of the basic situation to an almost unbearable level. The title character (Lily Ho) goes into action when her young nephew staggers into the family compound to report that his mother, Fei Fei's sister, has been raped and murdered. She learns that the culprit (James Nam) is the scion of a family, the Jins, who've long been friends with hers. Worse, he is her childhood friend and the man everyone considers her destined husband. He's fallen under bad influences, egged on by his retainers, one of whom calls in his brother, a formidable bandit with a small arsenal of weapons, to protect his master. The brother is a bigger villain than anyone; he murdered Fei Fei's brother-in-law and seeks to exploit the deteriorating situation, with his younger brother's help, to destroy both families. Meanwhile, the Jin family is coming apart at the seams. Dad (Li Peng-Fei) is ready to wash his hands of his wayward boy or hand him to Fei Fei, but Mom (Ching Lin), whom Dad blames for spoiling the boy, is protective to a fault. She's the Anthony Quinn character in this story, and pretty much the woman who wears the sword in the Jin household. When Fei Fei manages to strongarm Jin Lian Bai out of the compound to deliver him to the magistrate, the mother pursues with the untrustworthy retainers in tow, and they see a golden opportunity to escalate the feud between Jin and Feng....

Novice director Kao makes impressive use of a small town set in early fight scenes when Fei Fei and her nephew (Yuen Man Meng) are a team. Fighting with Lian Bai's buddies, Fei Fei fends off several attackers at one end of town while the kid struggles to escape another in a restaurant and stable. Commanding overhead shots sweep across town establishing the good guys' relative positions as they battle for their lives. The nephew has a story arc that might trouble western viewers. There's almost always an element of slapstick to the little guy with the silly tuft of hair on top as he falls on his face repeatedly trying to dismount his horse. Some of his escapes in the fight scene I mentioned are silly, including teeter-totter gags that were old before talkies. He meets cute with a young girl on a caravan, but any hope of a happy future is dashed when Lian Bai kills him during an escape attempt. Some people may be uncomfortable with such a traumatized child being used for comedy relief only to get brutally killed -- the film ends with Fei Fei weeping over his corpse -- but I suspect most people around the world are more ready to laugh or weep on short notice over the vicissitudes of life. The overall sadness of the picture may well reflect a more humane spirit in this particular director; Kuang wrote so much that it's hard to credit him with any singluar sensibility. Another director might have ended the picture with the deaths of the evil brothers; in a charming touch Fei Fei's mom and dad both ride to her rescue, while Lian Bai's dad doesn't buy the brothers' attempt to blame everything on the Fengs. Many martial arts films end with that sort of violent catharsis (see Lady Assassin in particular). Kao seems more interested in the emotional consequences for the survivors. If that's a personal touch then more power to her.

Wednesday, March 18, 2015

Pre-Code Capsules: CENTRAL PARK (1932)

Audiences today would almost certainly feel gypped by a feature film that ran under an hour, but Warner Bros. actually boasted of how much action they crammed into 57 minutes directed by John G. Adolfi, who usually directed George Arliss vehicles and died the year following Central Park's release. This is a Depression picture so our hero and heroine are poor. Rick (Wallace Ford) and Dot (Joan Blondell) bond while eyeballing lunch wagon cuisine they can't afford. When Rick gets into an unprovoked fight with the lunch man, Dot steals a sandwich and later shares it with her new friend. Rick later lands a temporary job washing police motorcycles while Dot gets embroiled in a criminal scheme to hijack the proceeds of a charity beauty contest. More of a dummy than Blondell usually plays, Dot is persuaded that the crooks are actually detectives carrying out a sting operation. Meanwhile, Officer Charlie (Guy Kibbee), who steered Rick to that job, struggles to conceal his failing eyesight from his superiors. It shouldn't be that big of a deal since his beat is little more than the Central Park Zoo, but when an escaped lunatic with a lion fixation sneaks in, he's too far away for Charlie to make him out clearly. Instead, the old man waves him through, mistaking him for a buddy, and the loon lets a lion out of his cage and gets the keeper mauled. The lion has an adventure of his own, getting locked inside a taxi cab for a good chunk of the picture, then let loose to run amok at a high-society party. It looks like bad comedy when he comes in through the kitchen and frightens a room full of acrobatic Negro cooks, but the white folks on the dance floor are just as terrified for what that's worth. Meanwhile, poor Charlie is suspended for his negligence and incapacity, but redeems himself in the pursuit of those beauty-contest bandits. He and Nick join forces to stop Nick Sarno (the reliably sinister Harold Huber), but it costs Charlie a rock to the head and a bullet in the vitals, and those things add up when you're an old man. So Charlie gets a sentimental exit as a reinstated officer in good standing and the poor boy gets the poor girl and you wish them luck. It's a studio film of course but it opens with an impressive aerial shot of the actual park that conveys its vastness quite nicely. Bookend montages of joggers, horseback riders, etc. tell us all this mayhem was just another day or so in the park. Like Big City Blues it portrays the big city as the land of exhilarating chaos where the possibility of anything happening nearly makes up for the lack of steady opportunity in those dark days. It's brevity helps put across the whirlwind nature of events and keeps you from thinking too long about how corny much of it is. And most likely you got a second feature wherever you saw it (if not at the Fox) or at least a cartoon and a newsreel. Central Park is a trifling item in the Warner Bros. canon but unlike many trifles today it has a proper sense of proportion.

Audiences today would almost certainly feel gypped by a feature film that ran under an hour, but Warner Bros. actually boasted of how much action they crammed into 57 minutes directed by John G. Adolfi, who usually directed George Arliss vehicles and died the year following Central Park's release. This is a Depression picture so our hero and heroine are poor. Rick (Wallace Ford) and Dot (Joan Blondell) bond while eyeballing lunch wagon cuisine they can't afford. When Rick gets into an unprovoked fight with the lunch man, Dot steals a sandwich and later shares it with her new friend. Rick later lands a temporary job washing police motorcycles while Dot gets embroiled in a criminal scheme to hijack the proceeds of a charity beauty contest. More of a dummy than Blondell usually plays, Dot is persuaded that the crooks are actually detectives carrying out a sting operation. Meanwhile, Officer Charlie (Guy Kibbee), who steered Rick to that job, struggles to conceal his failing eyesight from his superiors. It shouldn't be that big of a deal since his beat is little more than the Central Park Zoo, but when an escaped lunatic with a lion fixation sneaks in, he's too far away for Charlie to make him out clearly. Instead, the old man waves him through, mistaking him for a buddy, and the loon lets a lion out of his cage and gets the keeper mauled. The lion has an adventure of his own, getting locked inside a taxi cab for a good chunk of the picture, then let loose to run amok at a high-society party. It looks like bad comedy when he comes in through the kitchen and frightens a room full of acrobatic Negro cooks, but the white folks on the dance floor are just as terrified for what that's worth. Meanwhile, poor Charlie is suspended for his negligence and incapacity, but redeems himself in the pursuit of those beauty-contest bandits. He and Nick join forces to stop Nick Sarno (the reliably sinister Harold Huber), but it costs Charlie a rock to the head and a bullet in the vitals, and those things add up when you're an old man. So Charlie gets a sentimental exit as a reinstated officer in good standing and the poor boy gets the poor girl and you wish them luck. It's a studio film of course but it opens with an impressive aerial shot of the actual park that conveys its vastness quite nicely. Bookend montages of joggers, horseback riders, etc. tell us all this mayhem was just another day or so in the park. Like Big City Blues it portrays the big city as the land of exhilarating chaos where the possibility of anything happening nearly makes up for the lack of steady opportunity in those dark days. It's brevity helps put across the whirlwind nature of events and keeps you from thinking too long about how corny much of it is. And most likely you got a second feature wherever you saw it (if not at the Fox) or at least a cartoon and a newsreel. Central Park is a trifling item in the Warner Bros. canon but unlike many trifles today it has a proper sense of proportion.

Monday, March 16, 2015

REAL PULP FICTION: Arthur Leo Zagat's "Thunder Tomorrow," ARGOSY, March 16, 1940

By the time of this newest story, the Bunch, led by Dikar (born Dick Carr) has joined forces with some of the underground resistance that had developed despite all odds, and with colonies of "beast men" who are, for all intents and purposes, white trash. The Asafrics announce that all Americans must make a fresh loyalty pledge of face deportation to the wastelands of Africa and Asia. To boost American morale, the resistance decides that the small army coalescing near the Bunch's mountain in downstate New York must score some sort of symbolic victory. Their target is the old military academy at West Point, now used as an Afrasic base. Dikar's early attempt to scout the site goes bad quickly and he's imprisoned inside the fortress. Captured by two black soldiers, presumably native Africans (described by the resistance as "the best soldiers in the world"), Dikar is turned over to a jailer. He notices that the jailer "was brown-faced, not black like the other Asafrics." Readers familiar with pulp dialects would quickly notice that the "brown" jailer talks differently from the "black" soldiers.

'Washton,' the Asafric with Dikar said, 'this one fellah special prisoner for Colonel Wangsing. Something happen to him, all our skin get flogged off. Unstan?''Yassuh, Sahgent,' Washton answered, his eyes gleaming white in the dimness as he goggled at Dikar, 'Ah unnerstands. You wan' him put in a cell by hisself?'

The Asafrics talk in something like standard pulp pidgin English, while Washton talks in something pulp readers would recognize as American negro dialect. Zagat is ready to answer a question at least some readers must have asked since his series started: what happened to the American blacks? His answer, in this case at least, is that African Americans are among the resistance's most effective inside men. Washton -- born Benjamin Franklin George Washington -- surprises Dikar by arranging for his escape from West Point. He surprises our hero even more by identifying himself as Agent X-18 of the resistance's Secret Net of operatives. Dikar either doesn't remember seeing, or has never seen, an authentic African American. He can't comprehend why an "Asafric soldier" would help the Americans. Washton explains:

'Dat's the beauty paht of it. See, w'en de Asafrics fust came, dey figgered us cullud people would want to jine up wid dem against de whites, and dey sent out word we'd be welcom. Dey foun' out dey figgered wrong.

'Dey foun' out we wuz Americans fust an' cullud after. But dah wuz some of us got de notion dat we cud mebbe fight 'em better from de inside, so we did jine up.

'But suppose they found you out?' [Dikar asks]

'Dem what dey fin's out,' Washton said, 'takes a long time to die, but dem what dey don't jus' keep on wukkin. Lots uh de sabotage dat's been happenin is de wuk of cullud men.'

Washton has accumulated detailed knowledge of the West Point defenses in the forlorn hope that it would be of use to a real resistance army. Learning that a real army is actually on the way, his response is "Glory be to the Lawd!" To our eyes, Zagat is working at cross purposes. Washton is clearly meant to prove that neither Zagat nor his story is racist, yet this resistance hero talks like Amos or Andy. Dialect is more problematic now than it was 75 years ago. Today we perceive a stigma of inferiority when Zagat may simply have felt an artistic imperative to write black speech as he thought he'd heard it. There's no excuse, however, when Dikar temporarily leaves Washton alone in the forest on their way to the resistance camp, and our black patriot says, "It's awful dahk, heah, an' it's just come to me dat dey says dese heah woods is ha'nted." Really, Arthur Leo Zagat? Washton has been risking his life spying in the belly of the beast, not to mention breaking Dikar out, but because he's a Negro he's skeered of ghosts?

The point Zagat wants to make with Washton is a welcome one, but the way he writes this black hero (who predictably enough sacrifices his life for Dikar before this installment ends) tends to remind me that even D. W. Griffith had good blacks in The Birth of a Nation. They were the ones who stayed loyal to their old massas and defended them from the depredations of the carpetbaggers and the more vicious blacks. Zagat actually deserves more credit for emphasizing that infiltration was African Americans' own idea, but he'd deserve more still if he could imagine free blacks as ongoing protagonists in his epic rather than the faithful retainer type that Washton unfortunately resembles. Washton's heroic intervention alone doesn't change the essentially racial nature of the Asafric war against the U.S., but to be fair Zagat has several more episodes of the "Tomorrow" series to go in which to refine if not redeem his vision of American resistance.

Saturday, March 14, 2015

Too Much TV: THE 100 (2014-present)

Superhero fans who tuned into the CW network, first to watch Smallville and now to watch Arrow and Flash, learned over time that for their favorite shows to survive, apparently they had to conform to a so-called CW formula and become stereotypical CW shows. This entailed catering to the female gaze with shots of shirtless men and to the (presumably) female sensibility with soap-operaesque elements like romantic triangles and an unforgiving attitude toward keeping secrets. These had to be permanent parts of the program, comic book fans conceded with different degrees of grudging, if the superhero shows were to survive. What, then, to make of The 100, which flips this assumption on its head? The CW's postapocalyptic drama established its network bona fides early on but quickly went on to become almost the antithesis of a CW show. It remains one in the formulaic sense only insofar as the protagonists are young people who would be deemed pretty when they aren't covered in mud, blood or war paint. It has gone so far from the formula or stereotype that when we did get a sex scene near the end of the second season -- the finale aired March 11 -- it was jarring because that sort of thing hadn't happened on The 100 for a long time. Meanwhile, the show's growing fandom deemed it The CW's answer to Game of Thrones or The Walking Dead. The most fanatical dare compare it favorably to those pantheon shows. I can't judge, but there's certainly a similarity in tone that makes 100 an outlier on the CW schedule and most likely --since I don't watch the entire schedule -- its best show.

The 100 (fwiw, it's pronounced "the hundred," not "the one hundred") is historically part of the YA-dystopia trend for which The Hunger Games set the tone. Jason Rothenberg based the show with progressive looseness on a novel by Kass Morgan, who has written a sequel since the show debuted in which at least one character appears whom the show has killed. The situation is that a cluster of space stations has preserved human civilization for almost a century since a nuclear war on the surface of Earth. The "Ark's" oxygen systems are beginning to fail; soon there won't be enough air for all the people on board. While some of the political leadership considers drastic steps to save oxygen by killing people, an alternative plan develops to test whether the surface is once more habitable. Since no one's that certain about it, the idea is to send 100 expendable people -- juvenile offenders who would have been killed under the Ark's draconian justice system -- to Earth as canaries in the proverbial mineshaft. The plan has the virtue of getting 100 sets of lungs off the Ark no matter how the kids' exploration of Earth turns out. Our main character is Clarke Griffin (Eliza Taylor), who becomes a de facto leader of the kids on the ground by virtue of her tie to Abby (Paige Turco), a doctor and political leader who's a true believer in the project. They want to prove that the planet is habitable in order to get everyone on the ground before more are killed in the Ark's hysterical political environment. On the Ark, Abby's main antagonist is Marcus Kane (Henry Ian Cusick), a control freak who sometimes seems overeager to reduce the surplus population. On the ground, Clarke's antagonist proves to be Bellamy Blake (Bob Morley), who was condemned for harboring a secret sister (Octavia, played by Marie Avgeropoulos) in defiance of the Ark's one-child policy. While Clarke and her allies want to establish order, Bellamy sees the situation as an opportunity to break free from adult constraints, the kids becoming a law unto themselves.

Obviously the earth is habitable once more or else there wouldn't be much of a show. In fact, it's been habitable for quite a while, since the kids soon discover people (as well as various mutated monsters) who've been living in a new tribal society for generations. These "grounders" are hostile to the intruders, but an outsider among them, Lincoln (Ricky Whittle) befriends Octavia (after initially kidnapping her) and tries to act as an intermediary between his people and the "Sky people." Many grounders speak fluent 21st century American English but also lapse into their own recently-evolved patois; it's a rare element of comic relief when you can make out the slang origins of the tribal tongue while subtitles make their meaning clear to viewers. But there was little funny about the contacts of grounders and sky people in the first season, which climaxed with a mass attack which the 100 (actually a good deal less by then) repelled by igniting rocket fuel and killing hundreds of grounders.

In the post-battle confusion Clarke and others on both sides were captured by a third force and imprisoned on Mount Weather, where people went underground at the time of the war and preserved as much of civilization and technology as they could. The "mountain men" remain very susceptible to the residual radiation on the surface but dream of walking in the sunlight once more. Their scientists have experimented on grounders, hoping to extract some key to immunity from radiation. The sky people make even more promising subjects. The second season featured (without overstating) parallel generational struggles. In the mountain, President Dante Wallace (Raymond J. Berry) is overthrown by his son Cage (Johnny Whitworth) because he's reluctant to adopt Cage's emergency plan to extract the captive sky-people's bone marrow without their consent and at the likely cost of their lives. Once Clarke escapes from the mountain, she struggles to reassert her hard-won authority against her own mother, who has reached the surface with many other Arkers in escape pods. Discovering that Mt. Weather has many grounders imprisoned for experimentation, while others are turned into drug-addicted Reapers who hunt more grounders, and having escaped with her onetime enemy, the grounder chieftain Anya (Dichen Lachman), Clarke hopes to forge an alliance with the grounders to storm the mountain and liberate all its prisoners. With major complications along the way, the season builds toward an epic siege of Mt. Weather that turns under increasingly desperate circumstances into a war of extermination.

The 100 has earned a reputation, not to mention comparisons with the acclaimed shows mentioned earlier, as a program that goes there, that doesn't find the easy out of bad situations that would let characters keep their consciences clear. Clarke has to get her hands, and often the rest of her, both literally and figuratively dirty as she learns to be a leader in an unliberal world. It's also a show where, if anything can go wrong, it probably will. Clarke's idea of an alliance is almost aborted at the beginning, for instance, when newly placed Ark guards at her old camp shoot down Anya, mistaking both her and Clarke for hostiles. She has to steel herself to be ruthless, most recently under the mentorship of Lexa (Alycia Debnam Carey), the grounder Commander chosen Dalai Lama style to fit the show's pattern of powerful young women. Clarke has had to personally execute the man she loves in order to keep the peace. She has had to join Lexa in a conspiracy of silence that condemned dozens of their peoples to violent death Coventry style rather than betray to Mt. Weather by evacuating them from the target of a missile attack that they have an infiltrator inside the mountain. Most recently she has had to decide whether to kill all the denizens of Mt. Weather, including children, by flooding the complex with surface radiation in order to save her own people from death by bone-marrow extraction. That decision comes after she shot a captive Dante Wallace dead in an attempt to intimidate Cage into surrender, and that decision comes after Lexa taught her a final lesson in ruthless leadership by making a separate peace with the mountain, getting her people back while leaving the sky people to die. And for what it's worth, that comes after Lexa, who had outed herself as lesbian in an earlier episode, seduced Clarke and received no worse rebuff than that Clarke, very understandably, wasn't ready yet. All these experiences weigh heavily on our heroine, but Eliza Taylor bears the burden heroically, making Clarke one of the strongest heroines on TV.

While Clarke has an epic learning curve to climb, what really elevates The 100 is the way the show has let other characters evolve past our first impressions. Remember those antagonistic males from the early episodes? Marcus Kane has grown compassionately self-critical since then, realizing that he'd condemned people who probably didn't have to die, and has emerged as a voice of reason on the series. At the extreme moment of this week's season finale, while a chained captive in the mountain, he promises to get his people to donate bone marrow voluntarily (which was something like Dante Wallace's original idea) if Cage will only free them. Marcus has also stood up for Clarke against Abby, who is too often tempted to see the kids' leader as her little girl gone morally astray. Meanwhile, Bellamy (who is Clarke's love interest in the books) quickly developed a conscience and a sense of responsibility not just for his sister but for the rest of the kids. Most recently he's been the Die Hard style infiltrator inside Mt. Weather and the sky person most hopeful of sparing the mountain's innocent kids come the reckoning. In that time Bob Morley has developed the character impressively into a laconic all-business action hero. Bellamy's sister Octavia has gone native more than any of the original 100, thanks to her love of Lincoln, and has transformed from one of the most helpless characters into a savagely elegant warrior. Jasper Jordan (Devon Bostick), almost comically hapless in the first season, became a heroically wrathful figure as he emerged as the leader of the captives in the mountain after Clarke's escape. Most unexpectedly, perhaps the most-hated character of the first season, the murderous traitor John Murphy (Richard Harmon) has become almost an audience favorite as he flinches from the more unfathomably vicious behavior of supposed good guys but retains a sardonic to-hell-with-everything attitude. He'll figure more prominently next season as the sole surviving companion of Theolonius Jaha (Isiah Washington), the former Ark leader and last man to escape to Earth who led a mostly doomed quest to find a fabled City of Light and most likely met the Season Three big bad instead.

If Jaha has seemed to go mad during his quest, he isn't the worst case of a good guy gone bad. In fact, it's while Murphy watched with perhaps more shock than horror that Finn Collins (Thomas McDonell), Clarke's boyfriend (but also the beloved of the kids' late-arriving tech whiz Raven Reyes [Lindsey Morgan]), believing Clarke a captive of the grounders early in the second season, hysterically massacred a bunch of frightened villagers, including children. Finn had been the voice of peace and reason almost ad nauseum throughout the first season, but his second-season arc (culminating in the execution scene I mentioned above) showed that while the ordeal of survival might mature some people, or even wisen up elders, it can also break good people or drive them mad. Finn's death was also a major milestone for The 100 because it decisively decoupled the series from the sort of teen-drama storylines that supposedly defined CW programming. Not until Raven took a breather to get it on with a new boyfriend, apparently to cater to shippers who wanted to see more of the latter character, was there anything like romance on the show, unless you count Lexa's kiss of Clarke as something more than a political maneuver or a publicity stunt by the producers. To borrow the spiel from Arrow, The 100 had become something else. It's The CW's most uncompromising genre show, one that genre fans can watch without apology or embarrassment, and with maybe one exception that you'll learn of shortly, it's the best current series I watch, if not one of the best shows running. It'll be back this fall for a third season with its players increasingly scattered across a world full of menaces, as we learned in the latest cliffhanger, still waiting to be discovered.

The 100 (fwiw, it's pronounced "the hundred," not "the one hundred") is historically part of the YA-dystopia trend for which The Hunger Games set the tone. Jason Rothenberg based the show with progressive looseness on a novel by Kass Morgan, who has written a sequel since the show debuted in which at least one character appears whom the show has killed. The situation is that a cluster of space stations has preserved human civilization for almost a century since a nuclear war on the surface of Earth. The "Ark's" oxygen systems are beginning to fail; soon there won't be enough air for all the people on board. While some of the political leadership considers drastic steps to save oxygen by killing people, an alternative plan develops to test whether the surface is once more habitable. Since no one's that certain about it, the idea is to send 100 expendable people -- juvenile offenders who would have been killed under the Ark's draconian justice system -- to Earth as canaries in the proverbial mineshaft. The plan has the virtue of getting 100 sets of lungs off the Ark no matter how the kids' exploration of Earth turns out. Our main character is Clarke Griffin (Eliza Taylor), who becomes a de facto leader of the kids on the ground by virtue of her tie to Abby (Paige Turco), a doctor and political leader who's a true believer in the project. They want to prove that the planet is habitable in order to get everyone on the ground before more are killed in the Ark's hysterical political environment. On the Ark, Abby's main antagonist is Marcus Kane (Henry Ian Cusick), a control freak who sometimes seems overeager to reduce the surplus population. On the ground, Clarke's antagonist proves to be Bellamy Blake (Bob Morley), who was condemned for harboring a secret sister (Octavia, played by Marie Avgeropoulos) in defiance of the Ark's one-child policy. While Clarke and her allies want to establish order, Bellamy sees the situation as an opportunity to break free from adult constraints, the kids becoming a law unto themselves.

Obviously the earth is habitable once more or else there wouldn't be much of a show. In fact, it's been habitable for quite a while, since the kids soon discover people (as well as various mutated monsters) who've been living in a new tribal society for generations. These "grounders" are hostile to the intruders, but an outsider among them, Lincoln (Ricky Whittle) befriends Octavia (after initially kidnapping her) and tries to act as an intermediary between his people and the "Sky people." Many grounders speak fluent 21st century American English but also lapse into their own recently-evolved patois; it's a rare element of comic relief when you can make out the slang origins of the tribal tongue while subtitles make their meaning clear to viewers. But there was little funny about the contacts of grounders and sky people in the first season, which climaxed with a mass attack which the 100 (actually a good deal less by then) repelled by igniting rocket fuel and killing hundreds of grounders.

In the post-battle confusion Clarke and others on both sides were captured by a third force and imprisoned on Mount Weather, where people went underground at the time of the war and preserved as much of civilization and technology as they could. The "mountain men" remain very susceptible to the residual radiation on the surface but dream of walking in the sunlight once more. Their scientists have experimented on grounders, hoping to extract some key to immunity from radiation. The sky people make even more promising subjects. The second season featured (without overstating) parallel generational struggles. In the mountain, President Dante Wallace (Raymond J. Berry) is overthrown by his son Cage (Johnny Whitworth) because he's reluctant to adopt Cage's emergency plan to extract the captive sky-people's bone marrow without their consent and at the likely cost of their lives. Once Clarke escapes from the mountain, she struggles to reassert her hard-won authority against her own mother, who has reached the surface with many other Arkers in escape pods. Discovering that Mt. Weather has many grounders imprisoned for experimentation, while others are turned into drug-addicted Reapers who hunt more grounders, and having escaped with her onetime enemy, the grounder chieftain Anya (Dichen Lachman), Clarke hopes to forge an alliance with the grounders to storm the mountain and liberate all its prisoners. With major complications along the way, the season builds toward an epic siege of Mt. Weather that turns under increasingly desperate circumstances into a war of extermination.

The 100 has earned a reputation, not to mention comparisons with the acclaimed shows mentioned earlier, as a program that goes there, that doesn't find the easy out of bad situations that would let characters keep their consciences clear. Clarke has to get her hands, and often the rest of her, both literally and figuratively dirty as she learns to be a leader in an unliberal world. It's also a show where, if anything can go wrong, it probably will. Clarke's idea of an alliance is almost aborted at the beginning, for instance, when newly placed Ark guards at her old camp shoot down Anya, mistaking both her and Clarke for hostiles. She has to steel herself to be ruthless, most recently under the mentorship of Lexa (Alycia Debnam Carey), the grounder Commander chosen Dalai Lama style to fit the show's pattern of powerful young women. Clarke has had to personally execute the man she loves in order to keep the peace. She has had to join Lexa in a conspiracy of silence that condemned dozens of their peoples to violent death Coventry style rather than betray to Mt. Weather by evacuating them from the target of a missile attack that they have an infiltrator inside the mountain. Most recently she has had to decide whether to kill all the denizens of Mt. Weather, including children, by flooding the complex with surface radiation in order to save her own people from death by bone-marrow extraction. That decision comes after she shot a captive Dante Wallace dead in an attempt to intimidate Cage into surrender, and that decision comes after Lexa taught her a final lesson in ruthless leadership by making a separate peace with the mountain, getting her people back while leaving the sky people to die. And for what it's worth, that comes after Lexa, who had outed herself as lesbian in an earlier episode, seduced Clarke and received no worse rebuff than that Clarke, very understandably, wasn't ready yet. All these experiences weigh heavily on our heroine, but Eliza Taylor bears the burden heroically, making Clarke one of the strongest heroines on TV.

While Clarke has an epic learning curve to climb, what really elevates The 100 is the way the show has let other characters evolve past our first impressions. Remember those antagonistic males from the early episodes? Marcus Kane has grown compassionately self-critical since then, realizing that he'd condemned people who probably didn't have to die, and has emerged as a voice of reason on the series. At the extreme moment of this week's season finale, while a chained captive in the mountain, he promises to get his people to donate bone marrow voluntarily (which was something like Dante Wallace's original idea) if Cage will only free them. Marcus has also stood up for Clarke against Abby, who is too often tempted to see the kids' leader as her little girl gone morally astray. Meanwhile, Bellamy (who is Clarke's love interest in the books) quickly developed a conscience and a sense of responsibility not just for his sister but for the rest of the kids. Most recently he's been the Die Hard style infiltrator inside Mt. Weather and the sky person most hopeful of sparing the mountain's innocent kids come the reckoning. In that time Bob Morley has developed the character impressively into a laconic all-business action hero. Bellamy's sister Octavia has gone native more than any of the original 100, thanks to her love of Lincoln, and has transformed from one of the most helpless characters into a savagely elegant warrior. Jasper Jordan (Devon Bostick), almost comically hapless in the first season, became a heroically wrathful figure as he emerged as the leader of the captives in the mountain after Clarke's escape. Most unexpectedly, perhaps the most-hated character of the first season, the murderous traitor John Murphy (Richard Harmon) has become almost an audience favorite as he flinches from the more unfathomably vicious behavior of supposed good guys but retains a sardonic to-hell-with-everything attitude. He'll figure more prominently next season as the sole surviving companion of Theolonius Jaha (Isiah Washington), the former Ark leader and last man to escape to Earth who led a mostly doomed quest to find a fabled City of Light and most likely met the Season Three big bad instead.

If Jaha has seemed to go mad during his quest, he isn't the worst case of a good guy gone bad. In fact, it's while Murphy watched with perhaps more shock than horror that Finn Collins (Thomas McDonell), Clarke's boyfriend (but also the beloved of the kids' late-arriving tech whiz Raven Reyes [Lindsey Morgan]), believing Clarke a captive of the grounders early in the second season, hysterically massacred a bunch of frightened villagers, including children. Finn had been the voice of peace and reason almost ad nauseum throughout the first season, but his second-season arc (culminating in the execution scene I mentioned above) showed that while the ordeal of survival might mature some people, or even wisen up elders, it can also break good people or drive them mad. Finn's death was also a major milestone for The 100 because it decisively decoupled the series from the sort of teen-drama storylines that supposedly defined CW programming. Not until Raven took a breather to get it on with a new boyfriend, apparently to cater to shippers who wanted to see more of the latter character, was there anything like romance on the show, unless you count Lexa's kiss of Clarke as something more than a political maneuver or a publicity stunt by the producers. To borrow the spiel from Arrow, The 100 had become something else. It's The CW's most uncompromising genre show, one that genre fans can watch without apology or embarrassment, and with maybe one exception that you'll learn of shortly, it's the best current series I watch, if not one of the best shows running. It'll be back this fall for a third season with its players increasingly scattered across a world full of menaces, as we learned in the latest cliffhanger, still waiting to be discovered.

Friday, March 13, 2015

Pre-Code Capsules: BIG CITY BLUES (1932)

Naive youth (Eric Linden) hits the big city and gets hit up by city-slicker cousin (Walter Catlett). Cuz sez he knows everyone from the mayor to the head of the hotel; it's all a con. He's simply out to bleed the boy's bankroll dry. Boy meets girl (Joan Blondell) because the girl is one of the cousin's cronies. He may not know so many people as he claims but quite a few show up in our hero's hotel room for a booze party on the boy's dime. The noise arouses the house dick (Guy Kibbee) but he's bought off with a bottle of wine. Unbilled Humphrey Bogart gets into a brawl with unbilled Lyle Talbot and bottles fly. One beans a broad and croaks her. Everyone runs leaving our hero holding the bag, except that he runs, too. Blondell thinks twice about it and that gets her in trouble. Soon she and Linden are chasing each other through the city while the cops chase both. Linden ends up in a speakeasy where unbilled Clarence Muse sings. He's really good if that's his actual voice. Linden gambles what's left of his money, starts on a winning streak, stretches it too far and loses it all. The cops catch the kids and grill them good, but Kibbee cracks the case simply by stumbling into a closet where he keeps his hooch and finding Talbot hung up and over. The corpse conveniently holds half of a broken bottle. The other half, realistically enough, did not break but broke that poor dame's skull. Beaten, the boy returns to Indiana, but here director Mervyn LeRoy and writer Ward Morehouse, adapting his own play, twist the expected moral. Sure, the city beat the kid this time, but he plans to go back after he's saved some money. Blondell'll be waiting for him. What did he learn? That the city is no place for a sap like himself? Maybe, but that's his fault for being a sap, not the city's for being what it is. We thought we'd been set up for a morality play about small-town virtue smashed by the big bad city, with a moral recommending flight back to small-town comforts, but we should have figured Warner Bros. would say screw that. That studo loved the city too much to look down on it that way. Big City Blues is in ways a precursor of the "night from hell" genre of so many bad things happening to a hapless hero but LeRoy's city is an object of fascination rather than fear. Despite the title it's ultimately opposed to self-pity. Pre-Code is opposed to retreat and roots for whoever can get off the floor after a haymaker. Even if Linden only dreams of fighting another day then maybe he won for losing. It was the Depression and you took your victories wherever you found them. I wouldn't call the film a victory, but it's a fast and slightly furious hour or so that doesn't feel at all too short, and despite the grim tale at its heart it's kinda fun while it lasts.

Naive youth (Eric Linden) hits the big city and gets hit up by city-slicker cousin (Walter Catlett). Cuz sez he knows everyone from the mayor to the head of the hotel; it's all a con. He's simply out to bleed the boy's bankroll dry. Boy meets girl (Joan Blondell) because the girl is one of the cousin's cronies. He may not know so many people as he claims but quite a few show up in our hero's hotel room for a booze party on the boy's dime. The noise arouses the house dick (Guy Kibbee) but he's bought off with a bottle of wine. Unbilled Humphrey Bogart gets into a brawl with unbilled Lyle Talbot and bottles fly. One beans a broad and croaks her. Everyone runs leaving our hero holding the bag, except that he runs, too. Blondell thinks twice about it and that gets her in trouble. Soon she and Linden are chasing each other through the city while the cops chase both. Linden ends up in a speakeasy where unbilled Clarence Muse sings. He's really good if that's his actual voice. Linden gambles what's left of his money, starts on a winning streak, stretches it too far and loses it all. The cops catch the kids and grill them good, but Kibbee cracks the case simply by stumbling into a closet where he keeps his hooch and finding Talbot hung up and over. The corpse conveniently holds half of a broken bottle. The other half, realistically enough, did not break but broke that poor dame's skull. Beaten, the boy returns to Indiana, but here director Mervyn LeRoy and writer Ward Morehouse, adapting his own play, twist the expected moral. Sure, the city beat the kid this time, but he plans to go back after he's saved some money. Blondell'll be waiting for him. What did he learn? That the city is no place for a sap like himself? Maybe, but that's his fault for being a sap, not the city's for being what it is. We thought we'd been set up for a morality play about small-town virtue smashed by the big bad city, with a moral recommending flight back to small-town comforts, but we should have figured Warner Bros. would say screw that. That studo loved the city too much to look down on it that way. Big City Blues is in ways a precursor of the "night from hell" genre of so many bad things happening to a hapless hero but LeRoy's city is an object of fascination rather than fear. Despite the title it's ultimately opposed to self-pity. Pre-Code is opposed to retreat and roots for whoever can get off the floor after a haymaker. Even if Linden only dreams of fighting another day then maybe he won for losing. It was the Depression and you took your victories wherever you found them. I wouldn't call the film a victory, but it's a fast and slightly furious hour or so that doesn't feel at all too short, and despite the grim tale at its heart it's kinda fun while it lasts.

Wednesday, March 11, 2015

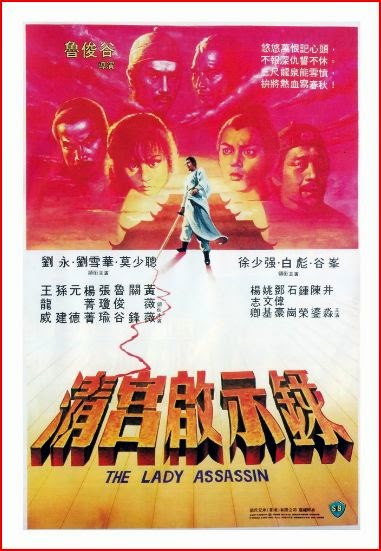

DVR Diary: THE LADY ASSASSIN (1983)

Lady Assassin works just as well as a historical drama as a wuxia film. The ruthlessness of the intrigue and its violent results might appeal to Game of Thrones fans, and the production values are often quite impressive. The art direction by Chen Ching-Shen and the cinematography by Ma Ching-Chiang often enhance the mood with expressive framing and lighting. I liked the acting as far as I can appreciate it with no knowledge of Chinese, the standouts being the two princes. Tony Liu is fine as the weaselly Fourth Prince, while Max Mok pulls off the more thankless task of conveying the tragic weakness and ultimate cluelessness of Fourteenth Prince. The martial arts might not appeal to purists. Lu Chin-Ku depends heavily on editing to assemble fight scenes but what he may sacrifice in verisimilitude he makes up for in pace and dramatic momentum. Some of the effects he tries don't work, especially the rapid-fire repetition of fighters' entrances. But when Lu and the editors really get going the fight scenes have the dynamic pictorial energy of the better superhero comics. They sometimes edit so rapidly that watching is like reading a comic from panel to panel. The team goes into overdrive for the final battle, when Lui Si Niang leads an attempt to assassinate the Emperor. As the editing gets faster than ever, the violence gets still more extreme. In the end, Lady Assassin is the sort of kung fu film I remember from my childhood that ends abruptly with an exhilarating kill. In fact, this film has two such moments within seconds of each other, with one villain cut in half after an exhausting battle and another cut in half lengthwise at the very last moment by the heroine's virtual orgasm of righteous murder. I admit that I was in suspense partly because I was afraid the film was going to run past the length of my DVR recording, but I suspect that audiences not operating under my time constraint would share my bloodthirsty exhilaration at the stunning finish. Lady Assassin wasn't the film I expected, but I suspect I'm better off for that.

Monday, March 9, 2015

Pre-Code Capsules: FLYING HIGH (1931)

Bert Lahr is one of the one-hit wonders of movie acting. That one hit so overshadowed a storied theatrical career, which climaxed with his starring role in the American premiere of Waiting For Godot, that his son, the acclaimed critic and biographer John Lahr, titled his father's story Notes On a Cowardly Lion. Except for theater historians, Lahr is now identified exclusively for his role in The Wizard of Oz. That's not for want of trying on Lahr's part. He was one of many successful stage comedians summoned to Hollywood in the early talkie ear to recreate Broadway hits. Lahr's was Flying High, a George White production adapted to the screen by director Charles Reisner and dance director Busby Berkeley. Lahr plays Rusty, an eccentric inventor if not an idiot savant who's built an "aerocropter" to compete in a big air show. Pat O'Brien plays a huckster who convinces Guy Kibbee (here married to future gossip maven Hedda Hopper) to invest in the unpromising looking device. Rusty is distracted from his work by marriage-mad Pansy Potts (Charlotte Greenwood), who ultimately goes up in the doomsday machine with him in the film's slapstick climax. Greenwood was a more established star at the time and more than holds her own with Lahr on the slapstick side. She wins our Pre-Code Play of the Film award for a scene in which Lahr repeatedly fends off her amorous advances by pushing her onto a couch. The long-legged and limber Greenwood sells the shove by yanking her legs up all the way to either side of her head, as if spreading them for her beloved, before hopping like a bunny for another round with him. As for Lahr, if 1931 movie audiences weren't asking what the fuss was about, as they did about many of the so-called nut comics imported from Broadway, then I will. He is profoundly unfunny. His schtick consists of an allegedly funny voice, a habit of repeating himself ("Put 'er there, boy, put 'er there!!") and, if not a catchphrase then a catch-noise for when he's alarmed. "Nyah nyah nyah!" is my best approximation of it. In short, it looks like no accident that Lahr scored his only real screen success when he played something other than a human being. Leaving him out of it, Flying High's main historical interest is as another prelude to Berkeley's epochal work at Warner Bros. a few years later. He's nearly there already, staging many mass formations for the overhead camera, but he doesn't yet have full control of the frame -- the angles often seem wrong somehow -- and hasn't yet broken the boundaries of a film set performance space to launch his fancies into full flight. If one scene sums this film up, it's the one where Lahr stumbles into the middle of one of the Berkeley numbers and flails about cluelessly. Everyone involved in this picture had some learning about movies yet to do.

Bert Lahr is one of the one-hit wonders of movie acting. That one hit so overshadowed a storied theatrical career, which climaxed with his starring role in the American premiere of Waiting For Godot, that his son, the acclaimed critic and biographer John Lahr, titled his father's story Notes On a Cowardly Lion. Except for theater historians, Lahr is now identified exclusively for his role in The Wizard of Oz. That's not for want of trying on Lahr's part. He was one of many successful stage comedians summoned to Hollywood in the early talkie ear to recreate Broadway hits. Lahr's was Flying High, a George White production adapted to the screen by director Charles Reisner and dance director Busby Berkeley. Lahr plays Rusty, an eccentric inventor if not an idiot savant who's built an "aerocropter" to compete in a big air show. Pat O'Brien plays a huckster who convinces Guy Kibbee (here married to future gossip maven Hedda Hopper) to invest in the unpromising looking device. Rusty is distracted from his work by marriage-mad Pansy Potts (Charlotte Greenwood), who ultimately goes up in the doomsday machine with him in the film's slapstick climax. Greenwood was a more established star at the time and more than holds her own with Lahr on the slapstick side. She wins our Pre-Code Play of the Film award for a scene in which Lahr repeatedly fends off her amorous advances by pushing her onto a couch. The long-legged and limber Greenwood sells the shove by yanking her legs up all the way to either side of her head, as if spreading them for her beloved, before hopping like a bunny for another round with him. As for Lahr, if 1931 movie audiences weren't asking what the fuss was about, as they did about many of the so-called nut comics imported from Broadway, then I will. He is profoundly unfunny. His schtick consists of an allegedly funny voice, a habit of repeating himself ("Put 'er there, boy, put 'er there!!") and, if not a catchphrase then a catch-noise for when he's alarmed. "Nyah nyah nyah!" is my best approximation of it. In short, it looks like no accident that Lahr scored his only real screen success when he played something other than a human being. Leaving him out of it, Flying High's main historical interest is as another prelude to Berkeley's epochal work at Warner Bros. a few years later. He's nearly there already, staging many mass formations for the overhead camera, but he doesn't yet have full control of the frame -- the angles often seem wrong somehow -- and hasn't yet broken the boundaries of a film set performance space to launch his fancies into full flight. If one scene sums this film up, it's the one where Lahr stumbles into the middle of one of the Berkeley numbers and flails about cluelessly. Everyone involved in this picture had some learning about movies yet to do.

Saturday, March 7, 2015

Pre-Code Parade: THE MYSTERIOUS DR. FU MANCHU (1929)

It seems that back in 1900, during the Boxer Rebellion, young Dr. Fu Manchu was one of the few Chinese in Peking to sympathize with the besieged westerners amid the anti-foreign rioting. Just before dying a British official entrusts his small daughter to one of Fu's servants and to Fu's own shelter. The humanitarian Fu resorts to hypnosis to calm the panicked little girl while an international expeditionary force enters the city to suppress the Boxers. In retreat, some of the Harmonious Fists take positions behind the walls of the Fu estate and open fire on the foreigners. Artillery is called down upon the Boxers, and in the chaos of war Fu Manchu's wife and child are killed. Bereaved and enraged, the doctor decides that the Boxers were right all along and that the foreigners are barbarians against who he vows revenge. Conveniently, he now has a white girl as his ward and eventual instrument of his vengeance.

As I understand it, none of this has anything to do with Rohmer's stories, which portray Fu Manchu as a visionary mad scientist bent on dominating the world for no better reason than that he believes he can. The doctor's antagonists over time develop a very grudging admiration for him, and some stories pit him against still worse villains -- he confronts a version of Hitler in Drums of Fu Manchu -- that make Fu look enlightened if not benevolent by comparison. But even though the doctor often exhibits a sort of chivalry, in the novels he remains an implacable menace never above torture to further his agenda. While Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu humanizes the doctor's origins, it also narrows his ambitions. Fu Manchu has no other plan, it seems, than to avenge the House of Fu by killing all the survivors of the Peking diplomatic compound, keeping score by painting the scales of a dragon tapestry that adorned his Peking home. His latest targets are Sir John Petrie and by his extension his son, the Dr. Petrie of the books (Neil "Commissioner Gordon" Hamilton). To the rescue comes the devil doctor's great nemesis, Nayland Smith (O.P. Heggie), but complicating matters, as long planned, is Lia (Jean Arthur), Fu Manchu's white ward and, when required, his hypnotized puppet. She still believes the doctor to be a benevolent physician until Smith sets her straight, but even when she repudiates her virtual father and takes shelter with young Petrie, Fu Manchu's reasserts his mental power over her across long distances, albeit with increasing difficulty as her feelings for Petrie grow stronger.

It is just about completely impossible to see Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu as its original audiences did. That's because the people of 1929 didn't know that Warner Oland, here playing the devil doctor, would soon become best known for playing Fu's diametric opposite, Hollywood's ultimate benign Oriental, Charlie Chan. In the first place Oland doesn't match Rohmer's famous physical description of Fu Manchu as tall, bald and clean-shaven, and in the second he can't help looking like Charlie Chan in Fu Manchu's clothes, at which point any sense of menace from him dissipates. He unwittingly adds an element of camp to a screenplay that may already have seemed camp to audiences, in the intentional sense. There's a very meta moment late in the picture when Fu Manchu condemns Petrie and Lia to death. He feels a need to dash Petrie's last hope:

I'm afraid my weird and Oriental methods may have misled your occidental mind into believing that this is nothing but a gigantic melodrama in which the detective's arrival at the last moment produces the happy ending. Don't deny it; I can see by your face that it is so....Permit me to settle that item once and for all.

The devil doctor than produces Nayland Smith bound and gagged. However, at the last moment Fu Manchu's elderly maid poisons him to rescue the white child she loved like a mother. Apparently dying -- Rohmer fans would know better -- Fu Manchu concedes that despite his earlier comments, the drama ends after all "in the usual way."