A randomly comprehensive survey of extraordinary movie experiences from the art house to the grindhouse, featuring the good, the bad, the ugly, but not the boring or the banal.

Wednesday, December 28, 2016

Debbie Reynolds (1932-2016)

At twenty, Reynolds' daughter, the late Carrie Fisher, starred in Star Wars. At twenty, Reynolds, who died one day after her daughter, starred in Singin' In the Rain. Blood will tell, it seems. There's a macabre sort of Hollywood finality in their virtual joint exit, as well as an oppressive exclamation point punctuating a year already infamous for the deaths of so many entertainment icons -- particularly pop singers like Reynolds. There's a permanent temptation to see the story of their lives in Fisher's novel Postcards From the Edge, or the adaptation she wrote for Mike Nichols' movie, in which Reynolds reportedly wanted to star as the mother character who finally was played by Shirley MacLaine. But Fisher herself downplayed the a clef aspect of the story, wanting recognition for creativity rather than reportage. Nevertheless, the Postcards legend keeps Reynolds somewhat in her daughter's shadow, and this week's news will do little to change that. It's worth emphasizing again that while Fisher graced the ultimate space opera movie, Reynolds was the romantic lead in the picture usually recognized as the greatest of all movie musicals, a major star of the 1950s and a fixture of the final years of the classic musical genre. At a certain point, around the time Carrie's dad, the singer Eddie Fisher, ditched her for the infamous Elizabeth Taylor, she arguably became more celebrity than entertainer, with fateful consequences for her daughter. Her late-life role as Carrie Fisher's mom only cemented that status, keeping her in the public eye between engagements in movies and television -- including a film written by Fisher in which she co-starred with Taylor. Since they'll be paired in people's minds forevermore, it might as well be said that Debbie Reynolds wasn't just Carrie Fisher's mom, but her peer as a star.

Tuesday, December 27, 2016

"Hope"

There is a terrible irony in Carrie Fisher's death almost exactly at the moment when the Star Wars franchise showed that it could do without her. In Rogue One: A Star Wars Story the last person we see on screen is a young Princess Leia, portrayed by a young actress wearing a CGI mask of a young Carrie Fisher. This came after The Force Awakens proved, for those who had not know from reading or watching gossip, that the years had not been kind to Fisher. It was just about impossible to imagine that film's General Leia having adventures like its Han Solo did, as played by a man more than a decade Fisher's senior. I suppose there's a gender double-standard behind that, that a septuagenarian accident-prone Harrison Ford should not seem more plausible in action than a Carrie Fisher then not yet 60 except that we've been conditioned to accept the one and not the other. That's where we are just the same, and while Ford can still make Blade Runner and maybe even Indiana Jones movies, Fisher died while promoting a memoir whose biggest selling point was her newly-disclosed affair with Ford. Despite all this, Fisher is assured of pop-culture immortality for the one big break she got. Princess Leia was a progressive figure in her time, less damsel in distress than leader and warrior, though her type had flourished in pulp fiction long before Star Wars. There's something compelling about her archetype that it took Disney to appreciate and exploit fully. Watching Rogue One, I thought it no accident that the Princess studio had made women the primary protagonists of its first two Star Wars movies. Thinking it over now, it seems as if Leia, rather than Luke, is their model -- the ideal type that would remain if you merged the Skywalker twins. You might imagine a young George Lucas today pitching his big idea to Disney and being asked why he even needed a Luke. The moral of this part of the story might be that Carrie Fisher and Star Wars were born too soon, but that doesn't really tell Fisher's story. She did a good job telling it herself, and it's arguably a tragedy that she, a proven writer, had to write about Star Wars to make money lately. For all we know she had other stories to tell, and not just about herself, but like it or not Star Wars is a defining part of her life, and when you see Princess Leia in her glory on the big screen you can't help thinking that Carrie Fisher deserved better from the rest of her life.

Tuesday, December 20, 2016

NEERJA (2016)

Watched cold, with no knowledge of Indian history, Ram Madhvani's film is an intense thriller with a highly sympathetic heroine and vicious villains, but for Indians, presumably, Neerja is no thriller at all. Its outcome would be known to everyone but those ignorant of their own history. Neerja Bhanot is a national heroine, a 22 year old model and stewardess who died rescuing hundreds of hostages from her hijacked jetliner in 1986. Inevitably, Neerja will be a different experience depending on whether you know the title character's story or not. If not, as was my case, the climax comes as a gut punch. But I imagine it was still a gut punch for Indian audiences earlier this year, since Sonam Kapoor gives such a vibrant and appealing performance in the title role that people probably were rooting for her to make it even when they knew better.

For Indian moviegoers there had to be great pathos every time Neerja's father asks, "Who's my brave girl?" and one of the ironies of the story, on film at least, is that she hardly feels brave before the crisis comes. In a flashback subplot, we learn that she ran away from the husband her parents arranged for her to marry. Hubby was quite the jerk, apparently, verbally and perhaps physically abusive, and Neerja's doting parents have the good sense to tell her she made the right decision. The film finds her in a happy place, the life of the party before she boards her final flight, though her mother would rather she stuck to modeling than fly in planes that could crash -- or who knows what else might happen?

Neerja's flight stops in Karachi, Pakistan, on the way to Frankfurt. In Karachi, a terrorist cell in fake uniforms storms the plane. These are oldschool terrorists from the good old days, Palestinian nationalists (and quite secular for all I know) loyal to Abu Nidal. Their object is to force the release of comrades held in a Cypriot prison. They're not the best-trained or best-briefed hijackers. They don't know that the cockpit is in an upper compartment of the plane, and in the initial confusion Neerja is able to warn the pilots that a hijack is under way, enabling them to escape through a hatch in the cockpit ceiling.

A waiting game begins. The terrorists demand that the pilots return to the plane, or that new pilots be sent. When a young Hindu man makes the mistake of identifying himself as an American citizen, the hijackers kill him right in front of Neerja to show negotiators on the tarmac that they mean business. Ordered to collect the passengers' passports, Neerja tells her crew to hide all the American passports, kicking them under the seats when necessary when their captors aren't looking. The hijackers rightly find it hard to believe that there are no other Americans on the plane, but Neerja's best intentions only move the British passengers to the front of the peril line.

We and Neerja can see that the terrorists are starting to crack. They're confused and frustrated, having expected to fly where they wanted, but their anger and anxiety only make them more dangerous. All it takes is for the lights to go out for hell to break loose. While all the terrorists are heinous villains, Neerja's writers and actors do a fine job individualizing them, making some more hateful or simply more crazy than others. Madhvani effectively creates a claustrophobic, impatient atmosphere of constantly ratcheting tension as the terrorists lose control and Neerja plans an exit strategy for the passengers. The climax is exhilarating terror as all the minor characters we've been introduced to Airport-style seem equally in mortal peril, while some make a stand against their tormentors United 93-style and Neerja shepherds as many people as possible out the emergency exits. From what little I've read the filmmakers have made Neerja's sacrifice even more heroic than the impressive reality, but I can understand the artistic need for dramatic license to keep the audience guessing when the end will come, or hoping against reason that she might escape. What comes after inevitably seems anticlimactic, but given how strongly the film has emphasized Neerja's bond with her parents, I suppose it's only right that they, and particularly her mother (Shabana Azmi), have the final words. My final word is that Neerja is a strong Indian contribution to the modern terrorist genre anchored by Sonam Kapoor's charismatic performance, and a sad reminder that this sort of thing has been going on longer than Americans may suppose.

For Indian moviegoers there had to be great pathos every time Neerja's father asks, "Who's my brave girl?" and one of the ironies of the story, on film at least, is that she hardly feels brave before the crisis comes. In a flashback subplot, we learn that she ran away from the husband her parents arranged for her to marry. Hubby was quite the jerk, apparently, verbally and perhaps physically abusive, and Neerja's doting parents have the good sense to tell her she made the right decision. The film finds her in a happy place, the life of the party before she boards her final flight, though her mother would rather she stuck to modeling than fly in planes that could crash -- or who knows what else might happen?

Neerja's flight stops in Karachi, Pakistan, on the way to Frankfurt. In Karachi, a terrorist cell in fake uniforms storms the plane. These are oldschool terrorists from the good old days, Palestinian nationalists (and quite secular for all I know) loyal to Abu Nidal. Their object is to force the release of comrades held in a Cypriot prison. They're not the best-trained or best-briefed hijackers. They don't know that the cockpit is in an upper compartment of the plane, and in the initial confusion Neerja is able to warn the pilots that a hijack is under way, enabling them to escape through a hatch in the cockpit ceiling.

A waiting game begins. The terrorists demand that the pilots return to the plane, or that new pilots be sent. When a young Hindu man makes the mistake of identifying himself as an American citizen, the hijackers kill him right in front of Neerja to show negotiators on the tarmac that they mean business. Ordered to collect the passengers' passports, Neerja tells her crew to hide all the American passports, kicking them under the seats when necessary when their captors aren't looking. The hijackers rightly find it hard to believe that there are no other Americans on the plane, but Neerja's best intentions only move the British passengers to the front of the peril line.

We and Neerja can see that the terrorists are starting to crack. They're confused and frustrated, having expected to fly where they wanted, but their anger and anxiety only make them more dangerous. All it takes is for the lights to go out for hell to break loose. While all the terrorists are heinous villains, Neerja's writers and actors do a fine job individualizing them, making some more hateful or simply more crazy than others. Madhvani effectively creates a claustrophobic, impatient atmosphere of constantly ratcheting tension as the terrorists lose control and Neerja plans an exit strategy for the passengers. The climax is exhilarating terror as all the minor characters we've been introduced to Airport-style seem equally in mortal peril, while some make a stand against their tormentors United 93-style and Neerja shepherds as many people as possible out the emergency exits. From what little I've read the filmmakers have made Neerja's sacrifice even more heroic than the impressive reality, but I can understand the artistic need for dramatic license to keep the audience guessing when the end will come, or hoping against reason that she might escape. What comes after inevitably seems anticlimactic, but given how strongly the film has emphasized Neerja's bond with her parents, I suppose it's only right that they, and particularly her mother (Shabana Azmi), have the final words. My final word is that Neerja is a strong Indian contribution to the modern terrorist genre anchored by Sonam Kapoor's charismatic performance, and a sad reminder that this sort of thing has been going on longer than Americans may suppose.

Saturday, December 17, 2016

On the Big Screen: ROGUE ONE: A STAR WARS STORY (2016)

While J. J. Abrams' The Force Awakens, released as the seventh episode of the Star Wars saga, felt like a fanfiction in its attention to the original movie characters and its repetition of plot points, Gareth Edwards' Rogue One -- apparently including significant contributions from Tony Gilroy -- feels like a real reboot of the franchise, despite its CGI resurrection of Peter Cushing and the wheezy line readings of James Earl Jones and Anthony Daniels. It introduces new notes of complexity and moral ambiguity into the legend of the rebellion against the Galactic Empire. It looks more like a rebellion for our time, divided into factions of varying degrees of ruthlessness and fanaticism, though as yet we've seen no space-opera equivalent of ISIS among the rebels against this particular tyranny. As everyone should know by now, Rogue One is an immediate prequel to the original Star Wars film -- or as I suppose we must call it now, A New Hope. It concerns the intrigues and slaughters that ended with the plans to the Death Star, including its crucial flaw, in the hands of Princess Leia. We learn now that the outrageous flaw was actually a deliberate act of design sabotage by captive scientist Galen Erso (Mads Mikkelsen), who now needs to get this secret detail to the rebels. In his captivity, however, he has missed the deterioration of the rebellion into factions. His great friend among the rebels is Saw Gerrera (Forest Whitaker), who rescued Galen's daughter Jyn when Imperial forces kidnapped Galen and killed his wife. Since then, the mutilated, ailing Gerrera -- he may have been envisioned as a rebel analogue to Darth Vader, though there's something of Col. Kurtz to him, too -- has alienated himself from the official rebellion, i.e. the Alliance, and wages guerrilla or terrorist war from his base on the desert planet Jedha. Galen persuades an Imperial pilot, Bodhi Rook (Riz Ahmed) to defect and fly to Jedha with a hologram in which Galen explains the flaw, but Gerrera has grown paranoid and keeps Bodhi imprisoned, thinking him an Imperial plant, if not an agent of some other enemy. The Alliance knows about the pilot's defection and wants information from him, but fears a hostile reception from Gerrera. Their solution is to recruit the grown-up Jyn Erso (Felicity Jones), an imprisoned criminal long since abandoned by Gerrera, as their entry to Jedha. Her Alliance escort, Cassian Andor (Diego Luna), is tasked with using whatever information can be had from Jedha to track down Galen Erso, extract him from Imperial custody if possible, or kill him if necessary.

That's enough synopsis to show that Rogue One is operating on an entirely different level from other Star Wars films. This is a Star Wars film where nothing or no one has to be cute; its idea of comedy relief is an acerbic tactical droid who jokes about "accidentally" shooting Jyn and dispassionately reminds the other characters of the probability of their deaths at any given moment. He's not wrong to be concerned, as the movie is as ruthless as its characters. It gives a knife's-edge quality to nearly every scene, at least in the first half of the movie. And its complexity extends to the other side, where the Death Star is the object of an institutional feud between the real initiator of the project, Orson Krennic (Ben Mendelsohn), who captured Galen Erso, and Grand Moff Tarkin, who switches on a dime from bullying skepticism to credit poaching, while Darth Vader serves as an impatient, contemptuous referee. Despite the Sith lord's hovering over events, this is a Star Wars film refreshingly free from preoccupation with the Jedi and their powers and bloodlines. The Force exists here only as an object of religious veneration that inspires and possibly empowers the acolytes of the Kyber temple on Jedha (played by Donnie "Ip Man" Yen and Jiang "who ever dreamed of the director of Devils on the Doorstep in a Star Wars film?" Wen). Though people may think of Star Wars as the saga of the Jedi -- The Force Awakens does nothing to contradict that -- the heroes of Rouge One are really more heroic for not being able to depend on superpowers, and the heightened odds against them gives the new film a dramatic tension long absent from the franchise.

There's a point where the picture's character changes, and though I don't think that's when Gilroy took over from Edwards, there's a little awkwardness in the transition. Basically, Rogue One stops being a "dirty war" spy thriller and becomes more of a doomed mission war movie, and once it becomes that all the ambiguities exposed in the first half are resolved or papered over. At one moment Jyn Erso is angry at the Alliance for having used and, arguably, betrayed her, and in the next she's trying to inspire the leading Alliance senators to attack the planet where the Death Star plans are actually stored -- by this point Galen himself can no longer help them -- with a rah-rah speech so heavy on "hope" that it has sparked suspicion of a contemporary political subtext, even though the concept of hope clearly isn't alien to Star Wars. Once we're past this bump, however, Rogue One rushes to the typical multilayered Star Wars climax, as our main band of heroes disperse on various missions on the planet while an Alliance fleet joins the fray once it looks like our heroes have a chance at success. I actually felt that the climax stretched out a little longer than it needed to, but there's no disputing the power and poignancy of it. The effect is spoiled a little by an admittedly badass run-in by Vader and a final word from a CGI Leia, but I feel like I'm nitpicking to mention these things. The real story is that Rogue One is the best Star Wars movie since The Empire Strikes Back, and in an ideal galaxy it, rather than The Force Awakens (its inferior in every respect) would be the model for the future evolution of the Star Wars universe. That's probably not going to happen, however, since I have a feeling this is going to get bad word of mouth for its lack of "fun" or nostalgic pandering. But it may be the most purely entertaining movie I've seen this year. It may not be "Star Wars" as far as some reviewers are concerned, but what counts is that it's a really good movie.

That's enough synopsis to show that Rogue One is operating on an entirely different level from other Star Wars films. This is a Star Wars film where nothing or no one has to be cute; its idea of comedy relief is an acerbic tactical droid who jokes about "accidentally" shooting Jyn and dispassionately reminds the other characters of the probability of their deaths at any given moment. He's not wrong to be concerned, as the movie is as ruthless as its characters. It gives a knife's-edge quality to nearly every scene, at least in the first half of the movie. And its complexity extends to the other side, where the Death Star is the object of an institutional feud between the real initiator of the project, Orson Krennic (Ben Mendelsohn), who captured Galen Erso, and Grand Moff Tarkin, who switches on a dime from bullying skepticism to credit poaching, while Darth Vader serves as an impatient, contemptuous referee. Despite the Sith lord's hovering over events, this is a Star Wars film refreshingly free from preoccupation with the Jedi and their powers and bloodlines. The Force exists here only as an object of religious veneration that inspires and possibly empowers the acolytes of the Kyber temple on Jedha (played by Donnie "Ip Man" Yen and Jiang "who ever dreamed of the director of Devils on the Doorstep in a Star Wars film?" Wen). Though people may think of Star Wars as the saga of the Jedi -- The Force Awakens does nothing to contradict that -- the heroes of Rouge One are really more heroic for not being able to depend on superpowers, and the heightened odds against them gives the new film a dramatic tension long absent from the franchise.

There's a point where the picture's character changes, and though I don't think that's when Gilroy took over from Edwards, there's a little awkwardness in the transition. Basically, Rogue One stops being a "dirty war" spy thriller and becomes more of a doomed mission war movie, and once it becomes that all the ambiguities exposed in the first half are resolved or papered over. At one moment Jyn Erso is angry at the Alliance for having used and, arguably, betrayed her, and in the next she's trying to inspire the leading Alliance senators to attack the planet where the Death Star plans are actually stored -- by this point Galen himself can no longer help them -- with a rah-rah speech so heavy on "hope" that it has sparked suspicion of a contemporary political subtext, even though the concept of hope clearly isn't alien to Star Wars. Once we're past this bump, however, Rogue One rushes to the typical multilayered Star Wars climax, as our main band of heroes disperse on various missions on the planet while an Alliance fleet joins the fray once it looks like our heroes have a chance at success. I actually felt that the climax stretched out a little longer than it needed to, but there's no disputing the power and poignancy of it. The effect is spoiled a little by an admittedly badass run-in by Vader and a final word from a CGI Leia, but I feel like I'm nitpicking to mention these things. The real story is that Rogue One is the best Star Wars movie since The Empire Strikes Back, and in an ideal galaxy it, rather than The Force Awakens (its inferior in every respect) would be the model for the future evolution of the Star Wars universe. That's probably not going to happen, however, since I have a feeling this is going to get bad word of mouth for its lack of "fun" or nostalgic pandering. But it may be the most purely entertaining movie I've seen this year. It may not be "Star Wars" as far as some reviewers are concerned, but what counts is that it's a really good movie.

Wednesday, December 14, 2016

National Film Registry Class of 2016

A relatively new end-of-year ritual in the U.S. is the naming of the latest films added to the Library of Congress's National Film Registry of movies with historic or artistic significance worthy of government-funded preservation. Following last year's list I chose 50 titles from the LOC websites' list of potentially worthy films as the most deserving of immediate inclusion. Three of those movies have made the 2016 list: Edwin S. Porter's early narrative film The Life of An American Fireman (1903), D. W. Griffith's innovative crime picture The Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912), and Buster Keaton's comic disaster picture Steamboat Bill Jr. (1928). My other 47 are still waiting. My problem, of course, is that I prioritize the past, presuming that the older stuff is by definition more historic and probably more in need of committed preservation, while the Registry often offers clickbait selections -- relatively recent popular films of dubious historic value but potential cultural importance that get the headlines in news reports and, so I suppose it's hoped, draw casual readers' attention to the complete list. I nominated nothing more recent than 1943 last year, but all but seven of this year's selections were made after that year. Many of these are films of lasting popularity, but I still question whether that alone should earn some of them places in this official canon. This year's selections are at the top of the list at the Registry web site; they include such modern touchstones as The Breakfast Club, The Princess Bride, Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, Thelma and Louise and The Lion King. Worthy as you may think some or all of these, I can't help thinking that they've butted ahead, or were escorted ahead of films at least equally deserving that have waited longer. On the other hand, the Registry is usually good about including documentary films and home movies of more obvious historical significance, even if a few selections each year forced me to do Google searches. Those informed me that Suzanne, Suzanne (1982) was a pioneer documentary addressing the linkage of drug abuse and abusive parenting, while the Reverend Solomon Sir Jones collection (see the films themselves here) includes very rare home movies of life in a 1920s black community in Oklahoma. Other documentaries added this year include the punk chronicle The Decline of Western Civilization (1981), the satirical compilation The Atomic Cafe (1982) and the drag-queen picture Paris Is Burning (1990). Then there are selections that are utterly whimsical or just plain nuts. To that category belongs the early Vitaphone vaudeville short The Beau Brummels (1928), starring the team of Shaw & Lee, which must be seen to be explained, to the extent that explanation is possible. Fortunately, lolevy uploaded the thing to YouTube, marred only slightly by some screen graphics. I'll leave you to look at it with the thought that it will definitely throw you back to a possibly unfathomable time.

Tuesday, December 13, 2016

DHEEPAN (2015)

Jacques Audiard's film won the Palme d'Or at last year's Cannes film festival but was blanked at the César awards, France's equivalent of the Oscars. Audiard already had a bunch of those, though, earning most of them for 2005's The Beat that My Heart Skipped and 2009's A Prophet, the film that really put him over around the world. Dheepan will remind people of Prophet in its use of genre archetypes to illustrate the integration of immigrants into French society. While Prophet is a gangster film, Dheepan turns out to be a sort of vigilante film, its hero a man with very special skills who gets pushed too far. Audiard supposedly was inspired by Sam Peckinpah's Straw Dogs, but movie buffs may see a more obvious influence by the film's climax.

The title character is an imposter; Dheepan isn't his real name. Sivadhasan (Jesusthasan Antonythasan) is a Tamil, one of the Hindu minority in Sri Lanka. He is also a Tamil Tiger, a soldier in the revolutionary/terrorist organization credited with inventing suicide bombing. Stuck in a refugee camp as the civil war winds down, he gets an opportunity to emigrate using the passports of a family -- husband, wife and daughter -- who were recently killed. He recruits a woman and girl who can vaguely pass for the people in the passport pictures, and soon enough the newly dubbed Dheepan and his new family are settled in a Paris housing project. It's not much of a family and not much of a life. The daughter, Illayal (Claudine Vinasithamby), is eager to learn French and make friends but is rebuffed by her new schoolmates and gets no emotional support from her aloof maternal unit, Yalini (Kaleaswari Srinivasan). Dheepan becomes a caretaker for the project, his comings and goings strictly regulated by the gangs who run the place, while Yalini becomes a home aide for the invalid father of one of the gangbangers.

Determined to make a home for himself and his quasi-family, Dheepan grows increasingly antagonistic toward the gangs and tries to draw a white line demarcating a "no fire zone" despite the gangs' taunts and threats. But when Yalini is trapped inside her employer's apartment during a gang hit, Dheepan has to cross the line to rescue her, taking a terrible toll with machete, car and gun along the way. Like some other viewers, the climactic rampage/rescue and the too-good-to-be-true vindication that follows, in which Dheepan and Yalini have added a child of their own to the family and appear to be solid citizens of a purged and peaceful project, put me in mind of the ironic denouement of Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver, in which Travis Bickle's killing spree, both a self-assigned rescue and a venting of frustration after a thwarted political assassination, gets him lionized by the press. By no means is Dheepan another Travis Bickle; our immigrant hero is far more sympathetic and sane than that despite his violent past. But Dheepan's ending is almost self-parodic in its pursuit of a happy ending. You can't help wondering whether Audiard is sincere or if he wants us to question his neatly generic resolution of all the storylines, or wondering why he'd want to throw it all into question. It's an odd false note on which to end an otherwise fine film, informatively observant of life in the projects and also rigorously reticent in its approach to vigilante violence. After Dheepan begins his assault, the camera remains focused tightly on him as he drives through opposition and shoots his way upstairs to save Yalini. Blink and you might miss the body flying past the driver's side window as he plows forward, though you can't miss the bodies that fall at his feet on the stairs. It's a cathartic moment in a film that ultimately seems uncertain of the finality or validity of catharsis, but despite its own uncertainty Dheepan remains a film well worth seeing on the migrant experience that to a great extent defines our time.

Dheepan follows a counterfeit family from Sri Lanka (above) to France (below)

The title character is an imposter; Dheepan isn't his real name. Sivadhasan (Jesusthasan Antonythasan) is a Tamil, one of the Hindu minority in Sri Lanka. He is also a Tamil Tiger, a soldier in the revolutionary/terrorist organization credited with inventing suicide bombing. Stuck in a refugee camp as the civil war winds down, he gets an opportunity to emigrate using the passports of a family -- husband, wife and daughter -- who were recently killed. He recruits a woman and girl who can vaguely pass for the people in the passport pictures, and soon enough the newly dubbed Dheepan and his new family are settled in a Paris housing project. It's not much of a family and not much of a life. The daughter, Illayal (Claudine Vinasithamby), is eager to learn French and make friends but is rebuffed by her new schoolmates and gets no emotional support from her aloof maternal unit, Yalini (Kaleaswari Srinivasan). Dheepan becomes a caretaker for the project, his comings and goings strictly regulated by the gangs who run the place, while Yalini becomes a home aide for the invalid father of one of the gangbangers.

Saturday, December 10, 2016

Pre-Code Parade: SHOW GIRL IN HOLLYWOOD (1930)

Mervyn LeRoy's film is a sequel to Show Girl, a silent film that only recently was rediscovered and restored, in which Alice White plays aspiring actress Dixie Dugan. Both films are based on novels by J. P. McEvoy, who later turned his character into the protagonist of a long-running comic strip. While the first film reportedly closed with Dixie destined for Broadway stardom, the sequel finds her and boyfriend writer Jimmy (Jack Mulhall) reeling from the flop of Jimmy's latest show, which both blame on a lovesick producer casting his girlfriend in the lead role while reducing Dixie to an understudy. She shows off what she could have done with one of the songs in an impromptu nightclub performance that impresses horndog Hollywood producer Frank Buelow (John Miljan). On his promise of a studio contract, Dixie goes to Hollywood, only to learn from Buelow's boss Sam Otis (Ford Sterling) that Buelow makes the same promise to dozens of girls wherever he goes. There's a waiting room full of them even as Dixie arrives. Discouraged Dixie has a chance encounter with her childhood idol, Donny Harris (Blanche Sweet), who's just been thrown off the lot by Buelow. Like every tourist, Dixie's awestruck by Donny's mansion, but the big house is little more than a facade. At age 32, Donny is finished in Hollywood. Only pride prevents her from selling the place. This being a musical, Donny abruptly sings some life advice to her admirer, but there's one thing she neglects to tell Dixie. We learn it a little later when she tries to ring up Frank Buelow. Donny is, in fact, Mrs. Buelow.

Buelow soon gets fired, but Otis presses on to produce a story Buelow had drafted. He soon learns that Buelow plagiarized the story from Dixie and Jimmy's flop show, but Otis and his yes men think they can do something with it just the same. Not knowing Dixie's tie to the show, Otis offers her a role in the movie because he feels sorry for her and sees some spirit in her. Meanwhile, he brings Jimmy to Hollywood and is stunned that the young man was dumb enough to take his first offer. It looks like a farce will break out when Otis insists on casting his starlet in the lead, while Jimmy insists on his girl, neither mentioning the name that would resolve the dispute, but fortunately Dixie herself appears in the office to abort that subplot. Remembering those who helped her, Dixie uses her newfound clout to get Donny a part in the picture, but the clout soon goes to her head. Impatient with retakes, she succumbs once more to Buelow's charms as he promises her better roles at his own independent production company. It's all a big lie intended to sabotage the production and spite Sam Otis, but it works almost too well. Dixie's prima-donna antics get her fired and do shut down the production, and that drives Donny, her comeback thwarted, to take poison. She makes a point of making a farewell call to Dixie, and that saves her life while scaring Dixie straight. Somehow Sam Otis resumes the production -- it probably has to do with Jimmy learning of Buelow's scheming and beating him up -- and the film closes with the triumphant Hollywood premiere of Rainbow Girl.

It would perhaps have been more triumphant had the Technicolor elements of the final reel survived. Color might have lent some visual interest to the inert goings on in the film-within-a-film that are only too representative of the dire state of movie musicals by 1930. The only interesting thing about it as it exists is one of those bizarre early-musical sets that has White emerging from the grinning mouth of some Moloch-like idol. Much more imaginative is LeRoy's filming of the filming of an earlier scene. The scene itself is stodgy, literally shot on a stage while the director sits in a front-row seat, but LeRoy turns the number into a montage, shooting from above as well as in front and cutting to the viewpoints of various technicians. It's the liveliest scene in a picture that awkwardly juxtaposes satire and a rather grim view of the film industry. Movies, it seems, never backed away from acknowledging how the industry devours its own. Donny Harris's story, though it has a happy ending, is an early example of this, as well as a prophecy of Blanche Sweet's own decline. My hunch is that Hollywood understood that these horror stories of falling or fallen stars only enriched the mythos and pathos of moviedom. Gods that can die might be worshiped all the more passionately. In a way Frank Buelow and Donny Harris are the spiritual parents of Norman Maine or Max Carey, the tragic protagonists of the A Star is Born/ What Price Hollywood? story, the perfected archetype combining the disreputable qualities of Buelow and the sympathetic qualities of Donny in one person. At the same time, Dixie Dugan is a less sympathetic version of the Vicki Lester archetype, less intelligent and less naive but more egotistical. Alice White has never gotten much love from critics and is savaged by Richard Barrios in his definitive early-musicals history A Song in the Dark, but while her limits are apparent I found her entertaining because her negatives complemented those of her character. White found her level eventually as a dumb-blonde type in the Warner Bros. stock company, which is what you might have guessed from watching Show Girl in Hollywood. I wouldn't call it a great or even good musical, but it's definitely one of the more interesting early musicals for reasons having little to do with music.

Buelow soon gets fired, but Otis presses on to produce a story Buelow had drafted. He soon learns that Buelow plagiarized the story from Dixie and Jimmy's flop show, but Otis and his yes men think they can do something with it just the same. Not knowing Dixie's tie to the show, Otis offers her a role in the movie because he feels sorry for her and sees some spirit in her. Meanwhile, he brings Jimmy to Hollywood and is stunned that the young man was dumb enough to take his first offer. It looks like a farce will break out when Otis insists on casting his starlet in the lead, while Jimmy insists on his girl, neither mentioning the name that would resolve the dispute, but fortunately Dixie herself appears in the office to abort that subplot. Remembering those who helped her, Dixie uses her newfound clout to get Donny a part in the picture, but the clout soon goes to her head. Impatient with retakes, she succumbs once more to Buelow's charms as he promises her better roles at his own independent production company. It's all a big lie intended to sabotage the production and spite Sam Otis, but it works almost too well. Dixie's prima-donna antics get her fired and do shut down the production, and that drives Donny, her comeback thwarted, to take poison. She makes a point of making a farewell call to Dixie, and that saves her life while scaring Dixie straight. Somehow Sam Otis resumes the production -- it probably has to do with Jimmy learning of Buelow's scheming and beating him up -- and the film closes with the triumphant Hollywood premiere of Rainbow Girl.

It would perhaps have been more triumphant had the Technicolor elements of the final reel survived. Color might have lent some visual interest to the inert goings on in the film-within-a-film that are only too representative of the dire state of movie musicals by 1930. The only interesting thing about it as it exists is one of those bizarre early-musical sets that has White emerging from the grinning mouth of some Moloch-like idol. Much more imaginative is LeRoy's filming of the filming of an earlier scene. The scene itself is stodgy, literally shot on a stage while the director sits in a front-row seat, but LeRoy turns the number into a montage, shooting from above as well as in front and cutting to the viewpoints of various technicians. It's the liveliest scene in a picture that awkwardly juxtaposes satire and a rather grim view of the film industry. Movies, it seems, never backed away from acknowledging how the industry devours its own. Donny Harris's story, though it has a happy ending, is an early example of this, as well as a prophecy of Blanche Sweet's own decline. My hunch is that Hollywood understood that these horror stories of falling or fallen stars only enriched the mythos and pathos of moviedom. Gods that can die might be worshiped all the more passionately. In a way Frank Buelow and Donny Harris are the spiritual parents of Norman Maine or Max Carey, the tragic protagonists of the A Star is Born/ What Price Hollywood? story, the perfected archetype combining the disreputable qualities of Buelow and the sympathetic qualities of Donny in one person. At the same time, Dixie Dugan is a less sympathetic version of the Vicki Lester archetype, less intelligent and less naive but more egotistical. Alice White has never gotten much love from critics and is savaged by Richard Barrios in his definitive early-musicals history A Song in the Dark, but while her limits are apparent I found her entertaining because her negatives complemented those of her character. White found her level eventually as a dumb-blonde type in the Warner Bros. stock company, which is what you might have guessed from watching Show Girl in Hollywood. I wouldn't call it a great or even good musical, but it's definitely one of the more interesting early musicals for reasons having little to do with music.

Tuesday, December 6, 2016

Too Much TV: "INVASION!" (November 28 - December 1, 2016)

The CW network runs superhero shows four nights each week. It picked up Supergirl after CBS decided the ratings didn't justify the expense, and promptly reduced expenses while actually improving the special effects and the overall tone of the show. While the show is now on the same network as The Flash, Arrow and Legends of Tomorrow, Supergirl remains in its own separate universe, despite what many fans saw as a golden opportunity to integrate the show into the larger "Arrowverse" when Flash did its version of DC Comics' Flashpoint event, in which Flash fundamentally altered reality by going back in time to stop the murder of his mother. It was most likely thought by Greg Berlanti and his writers that the Arrowverse was incompatible with the overwhelming everyday presence of not only Supergirl but Superman (who was introduced as a recurring character with an actual face and voice this fall), while Supergirl could not accommodate the everyday presence of all the costumed heroes who ply their trade on Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Thursdays. However, what's the point of a multiverse, which is what the CW now has, if the universes can't cross over?

Flash had already visited Supergirl's universe last year, when their shows were still on separate networks, so all you needed was a proper pretext for the Maid of Might to return the visit. Berlanti's team found this in a nearly 30 year old DC miniseries about an invasion of Earth by the Dominators, a species fearful of our planet's native and resident "metahumans," to use DC's catchall name for superbeings. On TV they would invade the Arrowverse Earth, giving Flash the idea that the best way to beat an alien invasion was with the help of a more powerful alien. So far, so good, except that Supergirl precedes Flash on the weekly schedule. Therefore, Flash and his colleague Cisco "Vibe" Ramon transported themselves to what we learned later was "Earth-38" (DC Comics hosts anywhere from 52 to Infinite Earths) after a couple of abortive attempts for the last few minutes of a Supergirl episode that had at most a thematic (and that perhaps accidental) relationship to the invasion concept. In it, Supergirl learned that her Kryptonian people had developed a bioweapon to repel alien invaders of their planet by killing anyone without native DNA. Evil Earthlings discovered the weapon (inexplicably called "Medusa" by the Kryptonians) and re-engineered it into a plague for non-human residents of Earth. I'm giving you just enough of the plot to explain why some Arrowverse fans, some of whom claimed to be watching Supergirl for the first time, felt that billing the episode as part of the Invasion! crossover was a bait and switch. Yet if anything this is typical of Berlanti's scattershot approach to storytelling, maddening to those who prefer the more focused, less crowded Marvel shows on Netflix. Berlanti's writers typically load their shows with vast casts of characters, then struggle to find things for all of them to do, often at the expense of the main character's storyline. So while Supergirl's near-irrelevance to the crossover was disappointing, it didn't scandalize me as it did other viewers.

It did, however, force an awkward chronology on the crossover. After seeing Flash recruit Supergirl to fight the invaders, viewers returned on Tuesday to find the Dominators just arriving on Earth. They were unappealing, unimpressive creatures, naked unlike their comics counterparts and apparently content to lope across the world on foot instead of traveling in vehicles outside their spaceship. Of course, both clothes and vehicles probably would have strained the special effects budget for these shows past its breaking point, but this apparent creative indifference to the series' villains betrayed their macguffinesque essence. The alien invasion, almost until the end, only provided that pretext for gathering all the Berlanti heroes together to bounce off each other. Even on that understanding of what Invasion! was actually about, the series only functioned as a crossover little more than 50% of that time, primarily during parts two (The Flash) and four (Legends of Tomorrow). By coincidence or design, part three would be the 100th episode of Arrow, the founding show of the whole shebang, and that hour inevitably was caught up in a conventional commemorative sort of storyline. At the end of Flash, the Dominators for some reason beamed Green Arrow, some of his supporting players, and former supporting player The Atom onto their spaceship. On Arrow they were imprisoned in individual pods and subjected to what was meant to be a mutually-reinforcing fantasy of how all their lives would have been different had Oliver Queen and his father not been lost at sea all those years ago. Why the Dominators should have done this is still unclear, though one character speculates afterward that the aliens may have been trying to harvest information from their subconsciences. If so, it benefited them little, and the device itself was severely defective, since our heroes almost immediately began having flashbacks to their real pasts. Their interactions only served to break the illusion down more quickly, it seems, but the whole thing was really a pretext, or should I say excuse, to bring back some actors whose characters had been killed off in previous seasons. While all this was going on, Flash and Supergirl fought some random supervillain who had some sort of technology they needed and there was much of the banter Berlanti fans enjoy so. On its own terms Arrow wasn't a bad episode, and that seems consistent with reports that the show has improved on its disastrous fourth season, but I'm sure more casual fans expected something more fully integrated into the main storyline of the week.

That left Legends of Tomorrow, which reportedly has improved on its disastrous first season, though you couldn't have convinced me with the first two episodes I saw this fall. Legends was the master class in Berlanti chaos theory; send a bunch of mismatched characters caroming in all directions and hope at least one of them does something fans will want to see more of. Since I never bothered reviewing this show last season, let me explain that a time traveler assembled a motley team of other shows' supporting characters and unimpressive newcomers to combat TV's underwhelming version of comics' immortal supervillain Vandal Savage.Having seen him off, the surviving "Legends" seek out alleged anomalies in time and usually cause more mischief than they correct. The show's approach to history is usually insulting, but it excels in using none of its characters to their full potential, except perhaps for the sardonic Mick "Heatwave" Rory (Dominic Purcell), once a foe of Flash and now the man with every episode's best lines. However improved it may be, I think there was an implicit acknowledgment that the Legends are the awkward squad of the Arrowverse in the fact that their part of the crossover played the most like a true crossover -- as it had to, being the conclusion -- and less like an episode of their own show.

While one of the Legends, Dr. Martin Stein, (Victor Garber) discovered a Flashpoint complication of his life in a daughter who didn't exist before Flash's meddling in time -- which somehow went undetected by the history-regulating Legends but was noticed by the Dominators -- the main character arc this hour belonged to Cisco Ramon, who despite helping Flash to Earth-38 back on Monday was on the outs with his fleet friend. In an inexplicable attempt to wreck the funniest character on all four shows, the Flash writers made Cisco mad at Flash for not going back in time to save his brother Dante, an occasional supporting character who had died offscreen. In time Cisco's anger cooled, only to rekindle in obnoxiously redundant fashion once he learned that Dante's death was not merely a sin of omission but a sin of Flash's commission, a consequence of the Flashpoint event. Cisco thus spent most of the crossover undermining what authority or credibility Flash had, only to face his comeuppance on Thursday, when he joined the Legends on a trip to 1951, the time when the Dominators first visited Earth, and helped rescue one of the aliens from some men in black bent on dissecting him. Cisco's thought was that the Dominators would remember this human kindness, but it actually only reinforced their belief that a breakout of superpowers such as the Legends displayed made Earth a threat requiring destruction. So Cisco learned that anyone can succumb to the temptation of good intentions and make honest, unwitting mistakes, and so he refuses to allow Flash to sacrifice himself by surrendering himself to the Dominators as they demanded, and presumably they'll be buddies again by the next regular episode of their show.

That only leaves the nearest thing to a proper invasion we see all week, and its defeat when Flash, Supergirl and Firestorm -- the composite being formed by the merger of Martin Stein and Jefferson Jackson (Franz Drameh) -- neutralize the dreaded metabomb, apparently the only such weapon the Dominators possess, or at least brought with them. It's all over then but the chest-beating, which comes in brazen form when Supergirl dubs Flash and Arrow "Earth's Mightiest Heroes" -- a term you may have heard elsewhere and may strike some as copyright infringement. I can say with some certainty that it was the best Legends of Tomorrow episode I've ever seen, but that's a case in which any praise is damning. But to be fair, while it was far less as a whole than it could have been, Invasion! was pretty entertaining on the geeky level it aimed for -- while Netflix/Marvel partisans and some comic book fans despise Berlanti's "cheesiness" that's what many people want from superhero shows -- and actually convinced me to give the new seasons of both Arrow and Legends another chance. I don't agree with those who prefer Berlanti's multiverse unconditionally to the "grimdark" tendencies of DC's movie universe, but I can understand and sympathize with what many still like about it, in all its earnest and endearing awkwardness.

Flash had already visited Supergirl's universe last year, when their shows were still on separate networks, so all you needed was a proper pretext for the Maid of Might to return the visit. Berlanti's team found this in a nearly 30 year old DC miniseries about an invasion of Earth by the Dominators, a species fearful of our planet's native and resident "metahumans," to use DC's catchall name for superbeings. On TV they would invade the Arrowverse Earth, giving Flash the idea that the best way to beat an alien invasion was with the help of a more powerful alien. So far, so good, except that Supergirl precedes Flash on the weekly schedule. Therefore, Flash and his colleague Cisco "Vibe" Ramon transported themselves to what we learned later was "Earth-38" (DC Comics hosts anywhere from 52 to Infinite Earths) after a couple of abortive attempts for the last few minutes of a Supergirl episode that had at most a thematic (and that perhaps accidental) relationship to the invasion concept. In it, Supergirl learned that her Kryptonian people had developed a bioweapon to repel alien invaders of their planet by killing anyone without native DNA. Evil Earthlings discovered the weapon (inexplicably called "Medusa" by the Kryptonians) and re-engineered it into a plague for non-human residents of Earth. I'm giving you just enough of the plot to explain why some Arrowverse fans, some of whom claimed to be watching Supergirl for the first time, felt that billing the episode as part of the Invasion! crossover was a bait and switch. Yet if anything this is typical of Berlanti's scattershot approach to storytelling, maddening to those who prefer the more focused, less crowded Marvel shows on Netflix. Berlanti's writers typically load their shows with vast casts of characters, then struggle to find things for all of them to do, often at the expense of the main character's storyline. So while Supergirl's near-irrelevance to the crossover was disappointing, it didn't scandalize me as it did other viewers.

It did, however, force an awkward chronology on the crossover. After seeing Flash recruit Supergirl to fight the invaders, viewers returned on Tuesday to find the Dominators just arriving on Earth. They were unappealing, unimpressive creatures, naked unlike their comics counterparts and apparently content to lope across the world on foot instead of traveling in vehicles outside their spaceship. Of course, both clothes and vehicles probably would have strained the special effects budget for these shows past its breaking point, but this apparent creative indifference to the series' villains betrayed their macguffinesque essence. The alien invasion, almost until the end, only provided that pretext for gathering all the Berlanti heroes together to bounce off each other. Even on that understanding of what Invasion! was actually about, the series only functioned as a crossover little more than 50% of that time, primarily during parts two (The Flash) and four (Legends of Tomorrow). By coincidence or design, part three would be the 100th episode of Arrow, the founding show of the whole shebang, and that hour inevitably was caught up in a conventional commemorative sort of storyline. At the end of Flash, the Dominators for some reason beamed Green Arrow, some of his supporting players, and former supporting player The Atom onto their spaceship. On Arrow they were imprisoned in individual pods and subjected to what was meant to be a mutually-reinforcing fantasy of how all their lives would have been different had Oliver Queen and his father not been lost at sea all those years ago. Why the Dominators should have done this is still unclear, though one character speculates afterward that the aliens may have been trying to harvest information from their subconsciences. If so, it benefited them little, and the device itself was severely defective, since our heroes almost immediately began having flashbacks to their real pasts. Their interactions only served to break the illusion down more quickly, it seems, but the whole thing was really a pretext, or should I say excuse, to bring back some actors whose characters had been killed off in previous seasons. While all this was going on, Flash and Supergirl fought some random supervillain who had some sort of technology they needed and there was much of the banter Berlanti fans enjoy so. On its own terms Arrow wasn't a bad episode, and that seems consistent with reports that the show has improved on its disastrous fourth season, but I'm sure more casual fans expected something more fully integrated into the main storyline of the week.

That left Legends of Tomorrow, which reportedly has improved on its disastrous first season, though you couldn't have convinced me with the first two episodes I saw this fall. Legends was the master class in Berlanti chaos theory; send a bunch of mismatched characters caroming in all directions and hope at least one of them does something fans will want to see more of. Since I never bothered reviewing this show last season, let me explain that a time traveler assembled a motley team of other shows' supporting characters and unimpressive newcomers to combat TV's underwhelming version of comics' immortal supervillain Vandal Savage.Having seen him off, the surviving "Legends" seek out alleged anomalies in time and usually cause more mischief than they correct. The show's approach to history is usually insulting, but it excels in using none of its characters to their full potential, except perhaps for the sardonic Mick "Heatwave" Rory (Dominic Purcell), once a foe of Flash and now the man with every episode's best lines. However improved it may be, I think there was an implicit acknowledgment that the Legends are the awkward squad of the Arrowverse in the fact that their part of the crossover played the most like a true crossover -- as it had to, being the conclusion -- and less like an episode of their own show.

While one of the Legends, Dr. Martin Stein, (Victor Garber) discovered a Flashpoint complication of his life in a daughter who didn't exist before Flash's meddling in time -- which somehow went undetected by the history-regulating Legends but was noticed by the Dominators -- the main character arc this hour belonged to Cisco Ramon, who despite helping Flash to Earth-38 back on Monday was on the outs with his fleet friend. In an inexplicable attempt to wreck the funniest character on all four shows, the Flash writers made Cisco mad at Flash for not going back in time to save his brother Dante, an occasional supporting character who had died offscreen. In time Cisco's anger cooled, only to rekindle in obnoxiously redundant fashion once he learned that Dante's death was not merely a sin of omission but a sin of Flash's commission, a consequence of the Flashpoint event. Cisco thus spent most of the crossover undermining what authority or credibility Flash had, only to face his comeuppance on Thursday, when he joined the Legends on a trip to 1951, the time when the Dominators first visited Earth, and helped rescue one of the aliens from some men in black bent on dissecting him. Cisco's thought was that the Dominators would remember this human kindness, but it actually only reinforced their belief that a breakout of superpowers such as the Legends displayed made Earth a threat requiring destruction. So Cisco learned that anyone can succumb to the temptation of good intentions and make honest, unwitting mistakes, and so he refuses to allow Flash to sacrifice himself by surrendering himself to the Dominators as they demanded, and presumably they'll be buddies again by the next regular episode of their show.

That only leaves the nearest thing to a proper invasion we see all week, and its defeat when Flash, Supergirl and Firestorm -- the composite being formed by the merger of Martin Stein and Jefferson Jackson (Franz Drameh) -- neutralize the dreaded metabomb, apparently the only such weapon the Dominators possess, or at least brought with them. It's all over then but the chest-beating, which comes in brazen form when Supergirl dubs Flash and Arrow "Earth's Mightiest Heroes" -- a term you may have heard elsewhere and may strike some as copyright infringement. I can say with some certainty that it was the best Legends of Tomorrow episode I've ever seen, but that's a case in which any praise is damning. But to be fair, while it was far less as a whole than it could have been, Invasion! was pretty entertaining on the geeky level it aimed for -- while Netflix/Marvel partisans and some comic book fans despise Berlanti's "cheesiness" that's what many people want from superhero shows -- and actually convinced me to give the new seasons of both Arrow and Legends another chance. I don't agree with those who prefer Berlanti's multiverse unconditionally to the "grimdark" tendencies of DC's movie universe, but I can understand and sympathize with what many still like about it, in all its earnest and endearing awkwardness.

Saturday, December 3, 2016

Pre-Code Parade: MASSACRE (1934)

Alan Crosland's modern-day western describes a slow-motion massacre: the systematic exploitation and swindling of Native Americans by corrupt Indian agents. It may not be as violent as what you saw in period westerns, but as the protagonist says, "It's a massacre any way you take it." He's an intriguingly ambiguous figure. Joe "Chief" Thunder Horse (Richard Barthelmess) is a riding, roping star of a wild west show playing, ironically enough, at Chicago's "Century of Progress" exposition. Joe plays the stereotyped bare-chested taciturn savage for the audience, but in reality he's as nearly deracinated as an Indian could be, admitting to his white girlfriend of the moment (Claire Dodd), who embarrasses him by redecorating one of her rooms into a mini museum of native artifacts, that "I wouldn't know a medicine man from a bootlegger" after using an old mortar and pestle as an ashtray. Barthelmess often seems the slow learner of the Warner Bros. stock company, but performing alongside people playing taciturn Indians all the time, he seems as much a glib, fast-talking smartass Warners hero as he ever would be. Joe has to go back on the rez when he learns that his father is gravely ill. Driving with his personal servant Sam (Clarence Muse) in his deluxe roadster -- his name is on the door, his face on the spare-tire case -- Joe rediscovers a dusty wasteland ruled over by the federal agent, Elihu B. Quissenberry (a reliably repulsive Dudley Digges) with his ally in swindling, the undertaker Shanks (Sidney Toler) and his minions, an alcoholic doctor (Arthur Hohl) and a puppet sheriff (Charles "Ming the Merciless" Middleton). They have a nice racket going on in which Shanks makes a mint on overpriced caskets and burials while Quissenberry enriches himself by administering estates. You can tell that Joe's dad isn't going to get proper medical attention from this lot, but Joe's been off the rez long enough to be shocked by it all, despite the efforts of agency secretary Lydia -- like himself, a college-educated Indian (Ann Dvorak) -- to wise him up. Joe may be seeing the world, but Lydia tells him there's a lot about the world they don't teach you at the old alma mater. Joe's old man was still a traditional man and Joe decides he should have a traditional funeral, which enrages Quissenberry more because it skips Shanks's funeral racket than because it represents some "pagan" revival.

Joe clearly has become a disruptive element whom the agency people should like to see leave as soon as possible to make $400 a week back in Chicago. But when Shanks rapes Joe's 15 year old sister -- they don't say the r-word of course, but it could not be more obvious within Pre-Code bounds -- it looks like they'll be stuck with him for a while. In a brutal modernization of the typical western chase, Joe in his car pursues Shanks in his until, cowboy style, he ropes the rapist. Slamming his brakes, he snaps Shanks out of his car and into the dirt, and drags him awhile before leaving him in a ditch. He'd already roughed up the agency doctor, so inevitably Joe gets arrested. Since Shanks is still alive it's only an assault charge that sends Joe to jail for 90 days after a kangaroo trial and leaves him a few hundred dollars poorer. He can afford that, but if Shanks dies he'll face a murder charge. Before that happens, Lydia arranges to break him out of jail so he can go to Washington D.C. and take his case directly to the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Since Joe has the most conspicuous getaway vehicle imaginable, Sam sacrifices himself by driving the Thunderhorse-mobile into an obvious trap while Joe hops a freight for the nation's capital. There, in keeping with Warners' favorable attitude toward the FDR presidency, our hero finds a sympathetic bureaucrat (Henry O'Neill) who's been trying to expose agency corruption but hasn't found anyone willing to testify about it. He sends Joe back to the rez with a federal attorney to investigate things, but Shanks has died in the interim and there's a murder warrant out for Joe. If it hadn't been plain before what Shanks had done to Joe's sister, the understanding that Joe will use the "unwritten law" defense to justify his killing should have left things clear even to the dimmest viewer. For that defense to work, however, the girl has to testify, but Quissenberry's minions have abducted her. That finally takes the tribe to the breaking point. They propose to raid the town to liberate Joe and burn the courthouse. Again, Massacre resists the temptation to portray this as a reversion to savagery. Just as Joe never reverts to the native address he identifies with wild west show hokum, the Indians look like your typical American lynch mob in modern dress, arriving by car as well as wagon or horseback, except that they're riding to the rescue. However, Joe joins those appealing to the rule of law as the courthouse burns, determined to stand trial like a good citizen until he learns that his sister has been kidnapped. That sets up one more ride to the rescue, one more horrifying revelation of the mistreatment of Indians, and a final dangerous showdown with a desperate Quissenberry.

While the climax teases a tragic finish, Massacre ends happily with Joe giving up show business for a new career as a conscientious representative of the U.S. government and a new life with Lydia. Compared to other movie exposes of reservation oppresses, Massacre is relatively unpatronizing toward Indians and is admirable in its commitment to modernity. The traditional funeral for Joe's father might not seem consistent with that commitment, but as Joe says, no one bothers Christians when they practice their religion, so why not let Indians worship their way? Maybe it's me, but I doubt Joe himself is very religious either way. Joe is one of Barthelmess's best talkie performances, along with the same year's A Modern Hero, and it's sad that Warner's dropped him just as he seemed to be getting the hang of talkie stardom. You can still see that the once-boyish Barthelmess, going on 39 when Massacre came out, was losing his movie-star looks. The bags under his eyes undermine Joe's alleged magnetism, but the actor puts enough charisma into his performance to make up for his fading beauty. Apart from Barthelmess, Massacre has obvious historic interest (if not continued relevance) for its portrayal of Native Americans' plight at a time when Calvin Coolidge's grant of citizenship to reservation Indians (as noted in the film) may have made some believe all problems were solved. Crosland's direction is solid, but special credit goes to whoever chose the desolate location where much of the film takes place. If anything, Massacre's story is too good to be true, but it's fun to see a western with a successful Indian uprising and the U.S. government cheering the Indians on.

Labels:

1930s,

Indians,

pre-Code,

U.S.,

Warner Bros.

Wednesday, November 30, 2016

Pre-Code Parade: Fatty Arbuckle speaks!

Tragedy is sometimes just a matter of timing. The tragedy of Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle is that he died in the middle of rewriting his tragic narrative. A heart attack claimed him at age 46, reportedly on the very day in 1933 that Warner Bros. signed him to a feature-film contract. Arbuckle had already finished Stage One of his comeback from an exile imposed on him despite a most emphatic acquittal after his third manslaughter trial for the death of Virginia Rappe. Merely to have taken part in the wild party where Rappe took ill, it seems, had been enough to justify making an example of Arbuckle at a time when Hollywood had been rocked by its first serious moral scandals. Like future blacklisted talent, Arbuckle never fully disappeared from the entertainment business. He performed in vaudeville and on Broadway, and returned to Hollywood to direct movies under a pseudonym. It seems right that he was called back before the camera during the Pre-Code era, but Arbuckle's six Big V shorts for Warners aren't really Pre-Code pictures in the salacious sense. You can divide them between nostalgic knockabouts in Arbuckle's old style (particularly How've You Been?, in which Fatty wastes his already-limited grocery store stock mindlessly hurling sacks of flour at a suspected criminal) and forays into contemporary nut comedy. I happen to like the nuttier films the best, but they're also the shorts in which Arbuckle most seems like an interchangeable part in the Big V machine.

Comedies like Close Relations and Tomalio (the latter finished the day before Arbuckle died) are more ensemble pieces than star vehicles, though Arbuckle's face fills the title cards. Big V had an eclectic stock company that included Shemp Howard (who must have had the longest hair on a Hollywood man at the time) a young Lionel Stander and the studio's most underrated comic, Charles Judels. With a range from the amiable to the apoplectic, Judels' signature was a closed-mouthed whine like a whistling kettle. Playing a psychotic Latin American general who can summon a firing squad to any location with his trusty whistle and insists on hearing the Lohengrin overture during executions, whether on a jukebox or performed by a three-piece band, Judels pretty much steals Tomalio from Arbuckle, who with his Kansas accent never sounds more like Oliver Hardy than in that short's clever opening shot. Fatty is shown in close-up sitting in the middle of the desert, angrily asking an unseen interlocutor, Hardy-style, "Why don't you help me?" The camera pulls back to indicate that Fatty is talking to a mule. Then we hear another voice, and the camera pulls further back to reveal that the mule is sitting on Fatty's sidekick for the picture. These shorts mostly have nice production values, though several opt for cheap animation effects to portray insect attacks or eruptions of Mexican jumping beans across a dinner table. They seem state of the art otherwise, but Arbuckle himself, however good-natured, seems old-fashioned in his standard costume with high-water pants and a voice that marks him as an oldschool rube. He still has some of his physical skills, best displayed in his juggling of kitchen implements and ingredients in Hello, Pop!, though he doesn't take the truly epic bumps he did in his youth. For that matter, the films themselves often flinch from large-scale destruction, usually setting up a violent collision, then cutting to someone's reaction shot before showing us the wreckage. It's an odd quirk that doesn't really harm the films very much.

Watching the Arbuckle shorts in a Warner Archive Big V collection was a nostalgic experience for me. I remember long long ago seeing In the Dough played in the wee hours on The Joe Franklin Show, at a time when I knew about Fatty Arbuckle but not about his Vitaphone shorts. Seeing him talk on screen late that night was like looking into an alternate reality. While I found all the shorts are all fairly entertaining -- Tomalio, Close Relations (Fatty is named an heir to a fortune but discovers his uncle [Judels] is a gouty lunatic) and Buzzin' Around (Fatty invents a shatterproof coating for ceramics but takes a jar of hard cider to town for the demonstration by mistake) are the best -- they do leave you wondering how much further Arbuckle might have gone had he lived. He was probably at the right studio, Warners being the home of Joe E. Brown, another exemplary physical comedian. Brown occupied his own separate universe at Warners, his films arguably more kiddie fare than the studio's typical Pre-Code product, and you can imagine Arbuckle making features in a similar sphere. Would we have seen Fatty among the comics in A Midsummer Night's Dream, or grappling with such absurdities as Sh! The Octopus? Would Warners have given him a chance in more adult fare, possibly as a younger version of Guy Kibbee? Or would Arbuckle have ended up making crap at Columbia alongside his great friend Buster Keaton by the end of the decade? Or would the backlash that led to Code Enforcement drive him from the screen again? The real tragedy of Fatty Arbuckle is that we can't know. His story ends all too abruptly on what he reportedly called the best day of his life.

Comedies like Close Relations and Tomalio (the latter finished the day before Arbuckle died) are more ensemble pieces than star vehicles, though Arbuckle's face fills the title cards. Big V had an eclectic stock company that included Shemp Howard (who must have had the longest hair on a Hollywood man at the time) a young Lionel Stander and the studio's most underrated comic, Charles Judels. With a range from the amiable to the apoplectic, Judels' signature was a closed-mouthed whine like a whistling kettle. Playing a psychotic Latin American general who can summon a firing squad to any location with his trusty whistle and insists on hearing the Lohengrin overture during executions, whether on a jukebox or performed by a three-piece band, Judels pretty much steals Tomalio from Arbuckle, who with his Kansas accent never sounds more like Oliver Hardy than in that short's clever opening shot. Fatty is shown in close-up sitting in the middle of the desert, angrily asking an unseen interlocutor, Hardy-style, "Why don't you help me?" The camera pulls back to indicate that Fatty is talking to a mule. Then we hear another voice, and the camera pulls further back to reveal that the mule is sitting on Fatty's sidekick for the picture. These shorts mostly have nice production values, though several opt for cheap animation effects to portray insect attacks or eruptions of Mexican jumping beans across a dinner table. They seem state of the art otherwise, but Arbuckle himself, however good-natured, seems old-fashioned in his standard costume with high-water pants and a voice that marks him as an oldschool rube. He still has some of his physical skills, best displayed in his juggling of kitchen implements and ingredients in Hello, Pop!, though he doesn't take the truly epic bumps he did in his youth. For that matter, the films themselves often flinch from large-scale destruction, usually setting up a violent collision, then cutting to someone's reaction shot before showing us the wreckage. It's an odd quirk that doesn't really harm the films very much.

Watching the Arbuckle shorts in a Warner Archive Big V collection was a nostalgic experience for me. I remember long long ago seeing In the Dough played in the wee hours on The Joe Franklin Show, at a time when I knew about Fatty Arbuckle but not about his Vitaphone shorts. Seeing him talk on screen late that night was like looking into an alternate reality. While I found all the shorts are all fairly entertaining -- Tomalio, Close Relations (Fatty is named an heir to a fortune but discovers his uncle [Judels] is a gouty lunatic) and Buzzin' Around (Fatty invents a shatterproof coating for ceramics but takes a jar of hard cider to town for the demonstration by mistake) are the best -- they do leave you wondering how much further Arbuckle might have gone had he lived. He was probably at the right studio, Warners being the home of Joe E. Brown, another exemplary physical comedian. Brown occupied his own separate universe at Warners, his films arguably more kiddie fare than the studio's typical Pre-Code product, and you can imagine Arbuckle making features in a similar sphere. Would we have seen Fatty among the comics in A Midsummer Night's Dream, or grappling with such absurdities as Sh! The Octopus? Would Warners have given him a chance in more adult fare, possibly as a younger version of Guy Kibbee? Or would Arbuckle have ended up making crap at Columbia alongside his great friend Buster Keaton by the end of the decade? Or would the backlash that led to Code Enforcement drive him from the screen again? The real tragedy of Fatty Arbuckle is that we can't know. His story ends all too abruptly on what he reportedly called the best day of his life.

Sunday, November 27, 2016

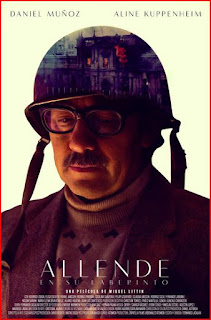

ALLENDE (Allende en su laberinto, 2014) and THE BATTLE OF CHILE (1975-9)

Santiago, Chile: September 11, 1973

Allende was the rare Marxist to win power by election, and wanted to prove that socialism could be achieved by peaceful means. Guzman's three-part documentary (I've only seen the two parts aired on TCM last week) is subtitled "the struggle of an unarmed people" and from all appearances the deck was stacked against Allende and his movement. Allende did not win a majority of the popular vote in 1970 -- he led the three-candidate field with approximately 36% -- and was chosen by the country's senate. But his fate was sealed almost from the start by the fact that his Popular Unity coalition never won control of the Chilean legislature. Conservatives and relative moderates could block many of his initiatives, but in turn they never had enough votes to impeach Allende. As Guzman stresses at every opportunity, the U.S. (under Nixon and Kissinger) opposed Allende from the beginning and provided both moral and material support to both the legal and the military opposition. The coup that toppled Allende was the second attempt of 1973, following a small but lethal uprising by a rogue unit that June. The first part of Guzman's documentary closes with ultimately dramatic footage of these soldiers firing directly at a cameraman as that brave man films his own murder. The anti-Allende majority in the legislature refused to declare a state of emergency after the coup, denying Allende the power to purge the military and other institutions, while many in Chile felt that Allende himself had far overstepped his constitutional bounds. The latter viewpoint is not taken seriously by Guzman and isn't addressed at all by Littin, and watching these films only launched me into a labyrinth of history without guiding me to the end.