Somewhere in San Francisco, a deli robbery disturbs the repose of Joe Wong, private detective. Surveying the scene from his window, he glumly puts on his gun and heads out the door. Where are you going, his secretary asks. "Going to quiet things down," he answers. He strolls into the deli, demanding, "Hey, where's my ham sandwich?" A gunman helpfully conducts him to a table, then resumes demanding money from the cashier. "Okay, here's your money," Joe says. Actually, it's a gun. In moments, the robbers are dead. Joe heads back to his office. "Forget about the ham sandwich," he says.

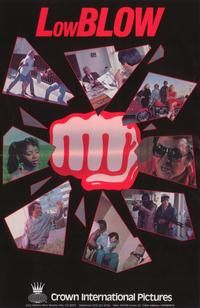

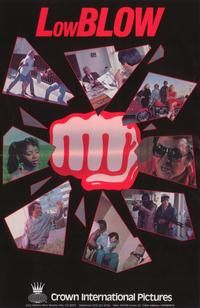

Two years after

Killpoint, we're back in the world of Leo Fong, Asian-Arkansan martial arts auteur. Fong is a man of many skills. For this occasion, he stars, acts, and wrote the script, leaving the direction to his

Killpoint helmer, Frank Harris. Compared to that minor apocalypse of gangs and gunrunners running amok,

Low Blow seems much less inspired, and definitely less well funded. It also hardly seems to merit an R rating; while it wallows in a certain impoverished scuzziness, it never delves to the depths of sleaze you'd want to reach with such a film. It's Fong's fourth film as a writer, but he's still a work in progress, playing with the building blocks of a script but never quite getting one to stand on top of another for long.

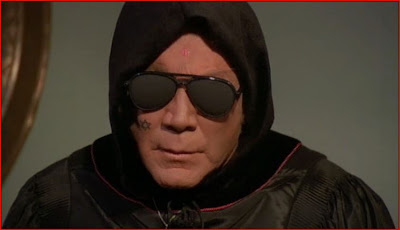

The bare description of

Low Blow promises more than the film delivers. Joe Wong is recruited to rescue a millionaire's daughter from a cult run by Yarakunda -- played by Cameron Mitchell. The prospect of Mitchell in Jim Jones mode ("It's very much like Jonestown" a cult expert tells Wong) had me stoked for this film, especially since Fong and Harris got a great crazy turn from Cam as the head gunrunner in

Killpoint. Two years later, Mitchell seems really out of it, unwell and uninspired. Whether this was because he was on or off the wagon, I just don't know. But it seems like Fong knew something was wrong, so he and Harris build up the role of Yarakunda's exploitative assistant, Karma. One year earlier, Akosua Busia was in

The Color Purple. Working for Leo Fong, she camps and cackles away as a cynical con artist with a fetish for Brach's salt-water taffy. It's probably the closest thing to actual acting in the picture.

Yarakunda and Karma run Unity Village, where the acolytes till the fields daily and listen to Karma's harangues. Their latest recruit is Karen Templeton, daughter of John Templeton of the vaunted Templeton International. How did Templeton get so rich? We get a sample of his savvy in a scene that has him riding through a seedy street in his limousine. He has the driver stop when he witnesses two muggers snatching an old lady's purse. Joe Wong is enjoying a bowl of chicken feet soup nearby when he hears the woman's screams. Abandoning his repast, he rushes out, chases down the muggers (who'll become recurring comedy relief characters), dodges a vicious purse attack and saves the day, before Templeton's eyes. This man knows talent when he sees it. He braves Wong's slobbovian office to hire the man to rescue Karen, whom the cultists call Purity.

Purse fu is no match for Leo Fong -- and this guy swings like a girl, anyway.

Check out those credentials on the door. And check out Troy Donahue as Mr. Templeton

Purity has given up her jewelry and signed a document of some kind, but even though the cultists know who she is, they make no great effort to exploit their asset. No matter how mercenary Karma is said to be ("She's not just from India, she just got out of prison," says the cult expert), there's no attempt to shake down Mr. Templeton or induce Purity to get more money. Yarakunda seems quite content to have his charges work the fields while he babbles about the river reaching the ocean. Mitchell talks so low so often that Busia has to repeat his words through a bullhorn so the faithful may hear. But I wonder if Fong and Harris had her do this because they knew that they'd be using an incredibly annoying wall-to-wall soundtrack of generic 80s instrumentals. In any event, I'm trying to tell you that there's no urgency to Purity's plight, nor is Joe Wong in a great hurry to save her after an initial foray into Unity Village. Pretending to be journalist "Jack Chan," he's taken on a tour of the minimalist compound. "Right around here I think we've got a nice setup," a guard doubling as a guide tells him, moments before another guard bops Wong on the head. A nice setup -- get it?

With the help of a disgruntled cultist sharing a cell with him, and after a session of ear biting and hair pulling courtesy of Karma, Joe sets a convenient wastebasket on fire to get a guard's attention. "Hey guard, fire in here," he says. Calling it yelling would give Fong too much credit, as he sounds about as exasperated as if the room were leaking rather than burning. He waves the pyre just under a barred window so the guard will get the idea. Suffice it to say that Joe fights his way out and into his dilapidated car, in which he must brave the dreaded barrier of empty cardboard boxes.

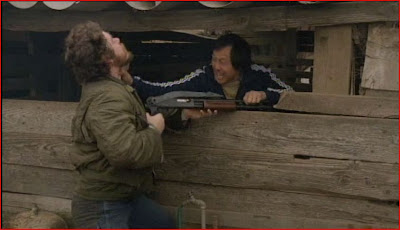

Somehow the cultists figure out "Jack Chan's" true identity and track him down to his house, somewhere in a junkyard. But the garbage and loose planks strewn about everywhere make Joe the master of his terrain, and that means it's "Home Alone" time for his attackers. The ensuing sequence is perplexingly non-violent. Yes, Joe hits people all over the place. But his strategy seems to consist of jumping someone, disarming them, and then leaving them behind and conscious so they can rejoin their buddies. One offender is even subjected to a puppy attack, such is the brutality of the moment. Finally tiring of the monotony, the perps pile into their car to flee, but Joe is just getting started. He rips out their wiring, smashes all the windows with a two-by-four, puts on a pair of goggles and grabs a circular saw. Before our eyes, and sometimes with clearly no one inside the car, he tears up the roof until he can peel it off like the lid of a tin can, at which point all the clowns now back inside the car spill out and run away up the road, presumably with Joe's best wishes.

Payback time should be coming, but Joe's approach to taking the offensive is rather like Colin Powell's. He is determined to have overwhelming force on his side. Toward this goal he's been scouting out likely allies like Duke, an overaged boxer, and Fuzzy, a fat guy with professional wrestling moves, and Chico, a stereotypical Hispanic knife fighter. They're still not enough to overcome Unity Village's formidable army of guards. They're led by future Tae-Bo tycoon Billy Blanks, after all. Also, Leo Fong has time to kill if he wants his film to get to the 80-minute mark. But I don't want to characterize what follows as a stalling tactic. Actually, it's at this point that Low Blow achieves genuinely inspired stupidity.

While John Templeton waits with dwindling patience for his daughter's freedom, Joe Wong tells his faithful secretary to call the press and announce a $20,000 toughman tournament. I assume the prize money is coming out of poor Templeton's pocket, since the gate isn't going to be much based on this crowd shot. We should note that the tournament is not a "Toughman" competition, strictly speaking. Those are boxing tournaments for people without professional skills. What Joe Wong stages is more like pit fighting. But what do I mean, "more like?" It literally is pit fighting. They've dug a hole in the earth and thrown people in it to fight each other.

At times, the tournament looks like a prototype of old-school mixed martial arts competitions, or early versions of those Kumite-style affairs that became their own movie genre in the late 80s. It's too bad more people didn't show, because there was something for everyone here.

Fat guys!

Ninjas!

Intergender!

Now Joe Wong has his private army of fighters for the dangerous assault on Unity Village. Strangely, though, considering the need for stealth, he didn't pick any ninjas. Stranger yet that he felt a need to judge their skills in unarmed combat, since they'll spend much of the climactic siege shooting down Yarakunda's guards like ducks in a gallery. The privilege of unarmed combat belongs to the master. He can use guns, too, but he also uses doors and other unorthodox attacks, including the emotionally challenging double handjob.

But the supreme moment comes when Joe fights the man whose car he destroyed back at the junkyard. "I got you now, Chinaman," this villain says in an instant of upper-handedness, "I think you owe me a car!" Joe promptly throws the car guy on his back, but the baddie is reaching for the gun in his shoulder holster.

I'll tell you now that Purity is rescued, Karma kills Yarakunda, and her own fate is left a mystery. I do this because the climax of the Joe vs the car guy fight is the real climax of Low Blow. You can tell it's an important moment because Fong and Harris prepared a special effect. The fact that there's a continuity problem between action and follow-through shouldn't affect our appreciation of their effort. Let's break it down shot by shot.

Joe has to act fast to beat car guy to the draw, so to speak. We see him desperately bearing down with his fist to subdue his antagonist.

The target: car guy's face. Kinda looks like Michael Medved, doesn't he?

IMPACT: But what's wrong with this picture?

Yes, you guessed it. Joe is destroying car guy's face with his foot rather than his fist. Harris has to take the blame for this one, because Fong was in his moment, getting into his Bruce Lee finishing move trance. Don't knock it: for him, this is acting.

For Low Blow Leo Fong had plenty of ideas that might have made a more effectively comical film in more skilled scripting hands, but he and Harris leave most of them laying on the screen. There are running gags like Joe's awful driving and his always getting a ticket, and the repeated appearances of the two purse-snatchers, who get beaten up by nearly everyone. There's politically incorrect repartee between Joe and Duke the boxer, the black man calling the Asian "Chinaman" and Joe calling Duke "boy." But our filmmakers are not really comedians by temperament, however comical their films turn out regardless. Fong has no sense of pacing, and his dialogue is rarely bad enough to be quotable.

The final third of the picture almost redeems the whole, but my knowledge that this team was capable of better (or "worse") work keeps me from really recommending the film. Low Blow is best appreciated by intensive students of 80s cheese and fans of Leo Fong, whose bland stoicism makes Chuck Norris look like a Method actor. Despite that, Fong's obvious dedication to making movies makes him a sympathetic figure in a period when the odds against getting on the big screen were growing ever longer. He has my respect.

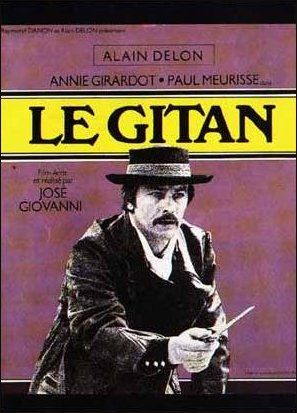

Here's how they sold it back in the day.

After Rev. Phantom was generous enough to post the entirety of Cannibal Mercenary in installments, and Nigel Wales posted the early shockumentary Beyond Bengal on I Spit On Your Taste, it only seemed fair for me to offer something to the movieblogging public. It just so happens that the work of an American visionary is available on Google Video.

After Rev. Phantom was generous enough to post the entirety of Cannibal Mercenary in installments, and Nigel Wales posted the early shockumentary Beyond Bengal on I Spit On Your Taste, it only seemed fair for me to offer something to the movieblogging public. It just so happens that the work of an American visionary is available on Google Video.