A randomly comprehensive survey of extraordinary movie experiences from the art house to the grindhouse, featuring the good, the bad, the ugly, but not the boring or the banal.

Sunday, December 30, 2018

AQUAMAN (2018) in SPOILERVISION

The new film is set some time after the events of Justice League. By now "the Aquaman" is more or less a known quantity, known or assumed to be an Atlantean, but not really a full-fledged public figure. He continues his low-key career of good deeds by rescuing a Russian submarine from some high-tech pirates but makes a long-term enemy of the son (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) of the pirate commander, whom Aquaman leaves to die for his bad choices, but who actually kills himself after tasking his son, soon to be known as Black Manta, with vengeance. Then it's back to hanging out with his dad (Temuera Morrison) who once upon a time had a fling with an Atlantean princess (Nicole Kidman) fleeing from an arranged marriage. This princess eventually was forced to return home, marry and birth a legitimate heir to the Altantean throne. When her affair and her terrestrial son became known, she was condemned to death. Her affair and her fate have embittered King Orm (Patrick Wilson) against the surface world, which has ages of pollution and depredation to answer for as well. Orm is trying to unite a number of undersea realms into a grand alliance that will confirm him as "Ocean Master" and enable him to wage war against the land. A clique of powerful insiders, including Orm's vizier (Willem Dafoe) and his bride-to-be (Amber Heard, seen briefly in Justice League) hope to avert war and see Aquaman, the man who could be King Arthur, as the answer to all problems. Orm is secretly collaborating with Black Manta to create provocations to drive the kingdoms into his embrace, while Aquaman, resenting Atlantis for killing his mom, rebuffs entreaties from below. Only when Orm launches a tidal-wave attack that nearly kills Arthur's dad does the hero agree to assert his claim against the fanatic king.

The story devolves into a Raiders-style treasure hunt for the sort of artifact that automatically confers legitimacy on he who wields it. The pursuit of this macguffin allows Aquaman to become a globetrotting James Bond style adventure and an all-out CGI explosion at the same time as Arthur and Mera follow clues above and below the surface in prickly partnership. All Atlanteans have superhuman strength and speed on land, so Mera is already a formidable heroine, but on top of that she has a special ability to manipulate water, pulling off stunts from drawing water out of Aquaman's scalp to attacking Atlantean goons with daggers of Sicilian wine. She's one of those longtime comics characters who's been upgraded in recent years from damsel-in-distress to kickass co-star, and whatever you think of Amber Heard's performance, the character certainly gets over. This film doesn't ask to be judged on its acting, however -- and that, given Wilson's vapid villainy, is probably a good thing. Aquaman is above all a pure spectacle, and you can believe while watching it that Justice League looked so cheap so often because most of Warner Bros' money was going into this film. It isn't that impressive at first, but kicks into super high gear in its relentless second half. It overwhelms you with imaginative battles between armies of shark-riding undersea cavalry and giant sentient crustaceans, among other things, filling the screen almost to overflowing with detail, and it also pulls off a tremendous extended parallel chase scene in Sicily as Mera fights off Atlantean pursuers across the rooftops while Aquaman deals with an upgraded Black Manta. There are times when throwing everything but the kitchen sink (though I may have missed that) at the audience is a good thing, and Aquaman is one of those occasions. For all that the future of a movie "universe" was riding on this film, it has an admirable nothing-to-lose recklessness to it, exemplified when at the end of his quest our hero encounters an immense sea monster, half kraken and half kaiju, and it talks to him -- in what must have been meant as a flagant F.U. to Disney, whose Mary Poppins reboot premiered the same week -- in the gravelly tones of Julie Andrews. If Justice League at nearly all points seemed cautious and stunted, Aquaman has the sort of creative insanity that when done right can justify a comic-book movie's existence. At the same time, Momoa clearly has more of a grip on the title character than he's ever had before as an actor, and may be able to take credit for molding Aquaman into his own self-image. If this was a make-or-break moment for the DC movie franchise, then Momoa should be a made man in Hollywood for literally saving a universe.

Saturday, December 22, 2018

On the Big Screen: MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS (2018)

A film adaptation of John Guy's biography has been in the works for more than a decade, but I could see people seeing the finished product, English-made as it is, as some kind of allegory for progressives refusing to support Hillary Clinton. The film flaunts its own progressiveness with aggressive inclusive casting, making the English ambassador to Scotland (Adrian Lester) and a member of Elizabeth's privy council black men and by adding a degree of homophobia to the sins of the Scots establishment given the relationship between Lord Danley (Jack Lowden) and Mary's minstrel-scribe David Rizzio (Ismael Cruz Cordova). The Brits are probably more used to inclusive casting by now thanks to Shakespearean theater giving worthy actors of color opportunities to play the great roles, but it seems harder to justify when some of the performers are little more than well-dressed extras. But by now I've reconciled myself to this violation of realism on film -- the "meta" quality of the stage may make inclusive casting less jarring -- by reminding myself that for generations Hollywood cast gentiles as semites in Bible stories with almost no one protesting. In any event, only two performers really count here -- and of the others Tennant is particularly bad in a one-dimensional heavily bearded role written with little understanding of how someone like Knox could be a successful demagogue. The real battle for supremacy on screen is between Ronan, who gets all the sympathy from the screenplay, and Robbie, whose past experience playing a she-devil in clown makeup no doubt recommended her for the role of Elizabeth I as envisioned here. To be fair, Elizabeth is portrayed as a tragic figure, no less compromised by refusing to mate than Mary is by taking husbands. She proves incapable of showing the solidarity with another woman that the film demands because her solution to the dilemma of a woman claiming power is l'etat, c'est moi, only with the opposite effect of the egoism we associate with that motto. Elizabeth must become the state at the expense of her femininity, her persistent and increasingly delusional vanity notwithstanding, and ultimately at the expense of effective empathy. Whether there was ever any chance of the two queens forming a matriarchal alliance given the inherent threat Mary presented to Elizabeth and the realities of Reformation geopolitics is less important to this version of the Mary story than Elizabeth's more timeless failure. But if this all sounds dismissive, let me close with praise for Saoirse Ronan. With the whole deck stacked in her character's favor, she does a great job portraying Mary as a three-dimensional, fallible heroine instead of a flawless martyr. Her effort alone just about justifies this enterprise.

Wednesday, December 19, 2018

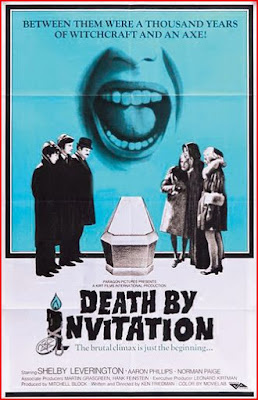

DVR Diary: DEATH BY INVITATION (1971)

Young and ambitious, Friedman made a film about revenge across the centuries. It opens with unconvincing scenes of 17th century New Netherland, where a woman is tried and condemned for witchcraft to the accompaniment of a loud heartbeat. We cut abruptly to the present day, where a distant descendant of the lead accuser (Aaron Phillips) -- you can tell because they look alike -- presides bibulously over the Vroot family dinner. Arriving late is family friend Lise (Shelby Leverington), who bears a strong resemblance in turn to the accused witch of yore. She entices young Roger to meet her later at her apartment -- despite the father's warning that he shouldn't hang out with "any of those way-out people" -- where she tells a strange story that deserves to be quoted in full, since it's the highlight of the film. Imagine the following told in a spaced-out monotone, like the incantation it apparently is:

Roger, do you know of the Southern Tribes? Well, it was the common practice for one certain tribe that the women were the hunters, while the men were domesticated. When the village needed food, the women would go out and hunt for it. The men on the other hand were allowed to grease [pronounced "greeze"] the women's bodies before the hunt, but they were never allowed off their knees while massaging the oil into the women. When a band of women found a prey, they would rush at it together, all stabbing wildly with their knives, until the blood of the animal flowed upon their bodies, often mixing with their own blood. Then without knives they would rip away at the flesh of the animal with their hands and mouths. They would rub their bodies against the ravaged animal, against his head, against his genitals, and after they had completely satisfied themselves upon the animal and upon each other they would drag the remains back to the men. Now the men would grovel on the ground when the women returned, exposing themselves, hoping to be chosen, for if they were chosen, and if they were good, they were given food.

[Lights cigarette]

But it happened once that one certain man found that he could hunt in the woods and bring in more food than the women could, and that with his rather large body he could satisfy four or more husbands. And with this man as their leader the men began to ignore the women, disobey their commands. They found they no longer needed the women. Whereupon the women came together and met, and they ["greezed"] and oiled their own bodies and they prepared to hunt that man, naked. We were -- they were naked. They tracked that man in the woods until they came upon him in the clearing. They fell upon him at once, ripping him open and eating his insides. The men were made to watch. They drank his blood and they chewed his bones until all of him was inside of them, but strangely they had raised themselves to passions far beyond their belief, and still writhing with pleasure and desire they fell upon the other men one by one, ripping them open and devouring them all.

Now that's a come-hither speech, and it works! Roger can't resist approaching this alluring and long-winded bacchant, and of course he gets what's coming to him, to the extent that Friedman's budget can visualize it. Practically speaking this means we get a shot of Roger from the neck down as several streams of blood begin to flow down his naked back. Lise's plan, you may not be surprised to learn, is to work her way through the Vroots, killing them indiscriminately, the women as well as the men. She takes out two daughters at once, though one is more or less accidental, the younger girl recoiling from the sight of her elder sister getting decapitated until she falls down a flight of stairs and brains herself. While synopses usually describe Lise as a descendant of the accused woman of the past, her slip of the tongue during her speech raises the possibility that she somehow is the fiend herself, though we have only the word of the accusers that that woman did anything wrong. In any event, while the local police are helpless to stop here -- they're comedy relief figures out of a 1940s B-movie -- Lise has not reckoned on another family friend, Jake (Norman Parker), whose virility overcomes her power. At the climax she tries repeatedly, in increasingly pathetic fashion, to repeat her Southern Tribes speech, as if she needs it to get sufficiently worked up, only to have Jake interrupt her repeatedly with his own come-ons, until old Peter Vroot charges in trying to finish what his ancestor started. Parker and Phillips share what might be, in spite of everything else, this film's strangest scene when Jake visits Peter at his office. Peter Vroot likes his Muzak, apparently, and has the stuff cranked up so loudly -- I recognized one familiar theme from a Tom and Jerry cartoon -- that he and Jake have to yell in order to hear each other in Peter's allegedly impressive sanctum sanctorum. You could believe that Friedman had the music playing on the set, and it may even be possible that he meant this to be funny. If so, it'd be one of those rare and serendipitous moments when a comedy scene is unintentionally funny. Some may say the whole film is that way, but that Southern Tribes bit is genuinely jaw-dropping and could well stop the snarkiest viewer in his or her tracks. To my shame, I found myself wishing that Friedman had had the means to put that story on film, though such a film probably wouldn't be something I could review here.

Saturday, December 15, 2018

On the Big Screen: THE MULE (2018)

Yet The Mule is as much a vanity project as a confessional, though the two aren't necessarily contradictory. Split the difference and call it one of Eastwood's most narcissistic pictures. He's reached a point at last when he's undeniably frail, though apparently healthy; any fantasy of Eastwood overcoming younger antagonists is no longer plausible. Nevertheless, and regardless of whatever Leo Sharp felt during his misadventures, Eastwood's Earl Stone never shows fear, veers between stoic and smartass except when dealing with family, and gets to cavort, so to speak, shirtless with topless women as a guest of honor at a cartel party. Perhaps because he's so plainly frail now, Eastwood seems to feel a greater need to reaffirm his virility than we've seen in past films. The main thing he wants to reaffirm, or perhaps prove once and for all to skeptics, is that he can act. The Mule is Oscar bait, its primary goal, apart from getting the bad taste of The 15:17 to Paris out of people's mouths, is to give Eastwood one more chance at a vindicating Best Actor award. Unfortunately, while he's loosened up a lot and is often quite natural and funny, he still can't do much with Schenk's bluntly on-the-nose dialogue in the family scenes. Overall, his performance may contribute to uncertainty about the tone of the picture. People, I think, were prepared to see this as some sort of tragic commentary on socioeconomic modernity -- look what this war hero was reduced to! -- but it plays more like a mildly black comedy because Earl Stone doesn't take his situation very seriously and seemingly would rather take nothing too seriously. When he feels guilty, it's all about his family and not in the least about running drugs. Eastwood probably would rather not have his character seen as a victim of anything other than changing times, and in its own way the film is very much about personal responsibility in the conservative sense of the term. Within his thespian limits, he gives a subtle performance that easily could be seen as a shallow one.

Social commentary is inescapable, however. Earl Stone's flower business is ruined, so he thinks, by the internet, and his downward spiral is accelerated by the logic of the bottom line. This becomes most obvious on the cartel side of the story. Earl is initially an object of amusement if not contempt by the cartel gangbangers, but his easygoing zero-fucks-given attitude and some quick thinking in a pinch eventually earns the criminals' admiration, to the point when the big boss (Andy Garcia) invites him to his big decadent party. Soon enough, however, a new regime takes over, eliminating the old boss because he'd become too "lenient." What the new boss demands, above all, is efficiency and the strictest time management, with the slightest deviance punishable by death. It's just a slightly exaggerated metaphor for the modern job market, or will seem that way to some viewers. Earl's success as a mule is a commentary unto itself. He's recruited not only for his perfect driving record, but because he, as an elderly white man, is one of the least likely people to be profiled as he drives around the country. The wisdom of his recruitment is demonstrated in scenes when plodding DEA agents (played with deceptive efficiency by Bradley Cooper and Michael Pena) reflexively profile after getting tipped off about a mule driving a black pickup. In one awkward scene, they pull over a hispanic-looking man who speaks no Spanish and frets loudly about the danger he's in. Later, staking out a motel where Earl is staying overnight, they see virtually everyone else there as their likely suspect. It all appears to prove a point against profiling; organized crime will respond to it by recruiting contrary to the profile. It's the same logic that makes the earlier cartel bosses indulgent toward Earl's eccentricities; his unpredictability will make him more difficult to track down. As Earl falls through the cracks in society, he can slip through some as well. In the end, though, The Mule is only superficially a crime film. It's more a character study than social commentary, though the latter often can reinforce the former. Good as it often is, it's not top-tier Eastwood but it'll be of lasting interest to auteurists for what it seems to try to say about the ultimate actor-turned-auteur of our time.

Wednesday, December 12, 2018

National Film Registry Class of 2018

A large bloc of "Movie To Be Announced" on the cable guide for TCM reminded me that the time had come for 25 more films of reputed historical value to be added to the Library of Congress's National Film Registry, and for some of them to play on the movie channel later today. As usual, we have an eclectic lot chosen according to criteria of generic and demographic diversity rather than by the sort of chronological priority that arguably should prevail when films are designated for preservation. I have no problem with any of this year's "diversity" choices (the headliner in that category is Brokeback Mountain), but as far as mainstream Hollywood is concerned this may be the most "meh" selection ever, ranging from a seemingly random Viola Dana picture from 1917 (The Girl Without a Soul -- not a horror film) to the stolid George Cukor musical My Fair Lady (which I suppose qualifies on the strength of its best picture Oscar) to the bland Broadcast News. The Registry has dutifully added another Keaton, another Welles, another Hitchcock and another Kubrick, but nothing seems historic about it. The two films that strike me as most deserving of the bunch are the documentary features Monterey Pop and Hearts and Minds, though I can't argue either with the 1908 actuality footage of an expedition to the Crow Nation or the supposed first-ever footage, from 1898, of a black couple kissing. More than ever, with the exceptions mentioned, the Registry announcement seems merely like a list of "great" movies, though the greatness of some (One-Eyed Jacks?) will remain subject to debate. Another look at the Registry website's list of "Some Films Not Yet Named to the Registry" reminds me that the annual selection could be far more exciting from a historical standpoint, though also probably far less compelling for the casual movie fan whose attention the curators crave. Of the 50 I selected from that list in 2015, only one -- Steamboat Bill Jr. -- has been added to the Registry. I realize my error, of course. I started from the beginning and made it to fifty films by 1943. That was very elitist of me, I guess.

Sunday, December 9, 2018

Too Much TV: THE CHILLING ADVENTURES OF SABRINA (2018 - ?)

Her problems are not solved. Working independently of Father Blackwood and the witch establishment to push Sabrina toward the dark side is a demoness who takes the form of Mrs. Wardwell (Michelle Gomez), a feminist high school teacher who becomes Sabrina's mentor. There's some deep ambiguity if not hypocrisy at work with this character. She does much to advance the show's feminist subtext, insinuating that the male-dominated with establishment fears female power, yet her ultimate goal seems to be to render Sabrina subservient to the very male Dark Lord. This becomes only slightly less murky when Wardwell reveals herself as the Lilith of Jewish/feminist myth, aspiring to equal standing to Satan, if not still more. Her special interest in Sabrina on the Dark Lord's behalf raises questions about Sabrina's own identity and destiny that remain to be answered and provide a hook for the second season that has already been filmed.

Sabrina is one of Greg Berlanti's productions but goes relatively light on the "lies are bad" hobbyhorse that powers many of his other shows. The writers, led by Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa, who writes a Sabrina comic book, are too busy world-building to indulge too much in teen genre-soap cliche. I think that makes the show's deeper dives into soapy sturm und drang all the more effective, more heartfelt because you're not seeing the characters going through the same contortions every single week. The writers are especially good on the family drama of the Spellman household, from the literal Cain-and-Abel dynamic of Zelda and Hilda (which borrows an idea from Alan Moore) to the sexually-frustrated Ambrose's (the show's token homosexual so far) embroilment in a slow-burning murder mystery. The best thing about the Spellman family is that their dynamics aren't set in stone; Zelda in particular proves to have more conscience and compassion than you would have guessed at first. As a whole, because the show has no monolithic vision of evil, all the characters seem more well-rounded than is usual in genre shows. Combined with Black Lightning on The CW -- I can't speak for Riverdale but Sabrina makes me more willing to give that show a chance -- this program shows that the Berlanti team is enjoying a strong second wind as its empire expands ... and I may have more evidence of that to report shortly....

Sunday, December 2, 2018

THE BALLAD OF BUSTER SCRUGGS (2018)

'Misanthrope?' I don't hate my fellow man, even when he's tiresome and sulky and tries to cheat at poker. I figure that's just a human material, and him that finds it cause for anger and dismay is just a fool for expecting better.

Perhaps feeling less capable of telling a feature-length story lately, the Coens reportedly contemplated embarking on series television. It was announced that they were creating a western anthology series for Netflix, but instead, apparently quitting while they were ahead, they delivered a feature-length collection of six stories: five of their own and an adaptation of Jack London's "All Gold Canyon." There's a variety of tone to the anthology that belies any stereotype of the Coens' character or philosophy and makes it truly reminiscent of the Twilight Zone of western anthology TV, Zane Grey Theater. It opens with a trolling provocation featuring Buster Scruggs (Tim Blake Nelson), a seemingly invincible and suprisingly lethal singing cowboy who ultimately yields, in the most cartoonish fashion, to a harmonica-playing stranger presumably representing a later era of westerns. It's a combination of what some may enjoy most and what others despise in the Coens' work, but as the film moves from episode to episode it grows less predictable, veering from the fateful absurdity of "Near Algodones," in which James Franco's hapless bank robber escapes one hanging only to be doomed to another, to the utter nihilism of "Meal Ticket," in which Liam Neeson exploits a limbless savant who performs recitations and murders him when he fails to draw crowds anymore, before following London in a more hopeful direction.

The longest episode -- or so it seemed, though not in a bad way -- is both the most romantic and the most tragic. "The Gal Who Got Rattled" is a wagon-train story of the deliberate courtship of a suddenly penniless pioneer woman (Zoe Kazan -- a veteran of Meek's Cutoff, by the way) and a wagonmaster's lieutenant (Bill Heck), as much motivated by monetary concerns as by feelings of ardor. There are elements in the story -- a dog with a maddening bark, a bankroll left in a corpse's clothes -- that lead you to suspect an absurdly happy ending until the story takes a twist out of nowhere when the girl and the wagonmaster (Grainger Hines) are caught alone by an Indian attack. The Coens have set up an archetypal frontier scenario of the sort that might get them scolded for their portrayal of Native Americans, down to the wagonmaster giving the girl a gun so she can kill herself if the Indians get him, in order to spare herself the fate worse than death, which here gets described in some detail. In a brilliantly swervy climax, it looks like he's driven the war band back only to get tricked by a seemingly riderless horse. The Coens keep our eyes on this scene, as the Indian moves in to take a scalp, only to get killed by the possum-playing wagonmaster. Hooray! -- except that the girl was just as fooled as the Indian was, and the finish could be considered an indictment of the mortal terror of Indians the old tales induced. This is a great piece of filmmaking on its own, but it could only happen in an anthology format, since it's too short to be a feature and a standalone story won't go on series TV nowadays.

The film ends on an eerie note with a story that's part Stagecoach, part Samuel Beckett, with a typical Coen cast of eccentrics and grotesques sharing a ride with two men who may be bounty hunters or may be far more sinister than that. On paper it's little more than an opportunity for a lot of newcomers to the Coens' world to tuck into their meaty flights of rhetoric, especially Chelcie Ross as an interminible trapper. One thing you can depend on, no matter what the content or tone of the tale, is that these westerners won't sound just like the people next door today; it's of a piece with their True Grit in many ways, and maybe meant to show that they weren't just mimicking Charles Portis's prose. While they portray The Ballad of Buster Scruggs onscreen as an old hardcover book with color illustrations, it reminded me more of the western pulp magazines I've come to enjoy reading in its simultaneous variety and consistency. The finished product may or may not count as a salvage job, but it still plays to the Coens' strengths while minimizing their weaknesses in a way that makes it a vast improvement over the tedious Hail Ceasar! The brothers may well have found the right medium in Netflix for this point in their career. Had it been packaged as a series, that would only have made it more clear, as it was clear a century ago, that great filmmaking isn't restricted to feature-length storytelling.