The filmmakers of Macedonia must be the most sophisticated on Earth. Consider that it took the United States a century to come up with a film as complexly and non-linearly structured as Pulp Fiction, but that in the very same year, the Former Yugoslav Republic came up with something just as sophisticated, perhaps more so -- and it was their very first movie! Well, movies were apparently made in Macedonia before, but this was the first one made after the country became independent, and Criterion calls it a first, so who are we to question?

We open with some children playing "ninja turtles." Their toys are real turtles, which the kids have "armed" with tiny swords. Now begins the first segment of the movie, "Words." It's about an Orthodox monk, Kiril, who has taken a vow of silence. What is he to do, then, when he finds that someone's been sleeping in his bed? It looks like a teenage boy, and thanks to subtitles we learn that the ragamuffin speaks Albanian, which the Macedonian Kiril doesn't understand. Kiril doesn't seem sure what to do, but lets the kid stay.

The next day brings a funeral, watched from a distance by what appears to be an English woman. Afterward, gunman come to the monastery. Their leader, Mitre, just buried his brother, and he thinks the girl who did the murder may be hiding on the premises. Despite vowing that "We'll find her even if she hides in America," they can't find her, though one gunman manages to machine gun a cat on a roof. That night, Kiril thinks he sees the girl, Zamira, then realizes he was dreaming. Then he starts again, and she's really there. Unfortunately, so are some of the other monks. "Time for you to leave," as they might say at the Shaolin monastery. Kiril abandons the religious life and his vow, resolving to take the girl out of the country, possibly all the way to Britain, where Kiril has an uncle who's a famous photographer. Who should turn up, however, but the girl's own grandfather, who welcomes her with a slap in the face. Her crime has started a war between the Christians and the Muslim Albanians, he fears; "Blood calls for blood now." He sneers at the notion that Kiril might care for her, and tries to prove his point by driving Kiril away. This works, except that Zamira breaks loose to join him -- only to be machine-gunned from behind. She dies with a smile, however.

We then see a naked woman weeping in a through the glass of a bathroom shower. This is our introduction to the second episode, "Faces." This is Ann, the Englishwoman we saw at the funeral of Mitre's brother. She reviews photos of refugees, soldiers, victims of war. A doctor calls to tell her she's pregnant. She vomits. On the street, walking with her mother, she encounters Alex, a Pulitzer-prize winning photographer just back from Bosnia -- Kiril's uncle, we presume, played by Rade Serbedzija, one of Hollywood's all-purpose foreigners. He's quit his photojournalism gig because he didn't want to take sides in the Yugoslav wars. Later, in a cab, Ann asks if something happened to provoke his decision. "I killed," Alex explains. He intends to go back to his home town in Macedonia, and wants Ann to come along. She doesn't. Instead, we see her at a tense dinner with Nick, her ex-husband, made more tense by the boorish behavior of some Balkan(?) thug at the restaurant bar, who picks a fight with a waiter and starts a larger brawl.

"At least they weren't from Ulster," Nick laughs after the dust has cleared a little. "I'm from Ulster, sir," the headwaiter protests. So it's a still more awkward dinner as Nick offers a toast: "Here's to civil wars becoming more civil when they come over here." Nick and Ann argue, and she's convinced him not to leave, telling him she still loves him, when the thug reappears, less civil, if that's possible, than before....

Abruptly, we're back in Macedonia, and Alex is off a plane and onto a bus heading into some familiar countryside. This is the third and final segment, "Pictures." This is his first visit in 16 years. In the village, we recognize a red-haired kid as one of Mitre's goons. Alex neatly disarms him as heads off, gun in tow, to see his cousin Bojan. His memories must still be vivid, for he pulls an old water pistol out of a niche in a wall on his way. His old home is nearly an empty shell, but has a bed he can sleep in overnight. He finally meets Bojan and Mitre the next day, but he has another reunion in mind, with Hana Halili, an old Muslim flame, the daughter of Zekir, who tells Alex that "Blood is in the air." We see the baptism, and we see a local vet helping a sheep give birth to two lambs. Alex writes a letter to Ann explaining what he meant by "I killed." He blames himself for a gunman shooting a victim in order to give him a good photo subject. Then the news spreads that Bojan has been fatally stabbed. But by whom? And when is this happening -- when did it happen, exactly?...

The trailer will not help you piece things together.

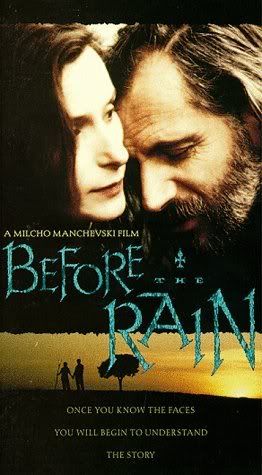

Not only has director Milcho Manchevski presented his episodes out of proper chronological order, but he's also shifted time in the middle of one of the episodes. We don't realize this until sometime later in the film, at which point we realize that much of what we saw in that episode was a flashback. We find ourselves expecting certain scenes, like a meeting between Alex and Kiril, that actually can't happen. At the same time, there are several parallel scenes in different episodes. In "Pictures," Alex has a dream of Hana, followed by a true vision, just as Kiril does with Zamira in "Words." Similarly, a moment in "Pictures" when Alex shows his back to his trigger-happy relatives mirrors Zamira's final moments in the first episode. There are other elements common to all three episodes. The same Beastie Boys rap plays in different snippets in each one, for instance, and some wisdom from a monk is repeated in the form of London graffiti: "Time doesn't wait, and the circle is not round." This is apparently the moral of the movie, and one way to read it is to understand that we can't see the same events the same way every time. Another way is to note that the film itself does not form a perfect circle, since it sort of knots in the middle. Either way, Before the Rain is the sort of movie that is impossible to watch in the same way the second time around. The real test of its staying power would really be the third viewing, since many people would spend the second viewing noticing patterns they might have missed before or trying to pinpoint the time shifts in the middle episode. Once the structural novelty wears off, I think the film will stand as a fairly predictable lamentation of Balkan horrors, augmented by a strong multilingual performance from Serbedzija, who earned some international stardom for his work.

As much as I'd like to compliment the Macedonians for a good first effort, I wonder whether Before the Rain is really more of an international than a Macedonian movie. It looks like something meant for film festivals and art house theaters rather than the Skopje multiplex. Maybe we've yet to see what an authentic popular Macedonian cinema might look like, though this film gives some reason to fear that it would have much to do with killing Albanians. I don't doubt that Manchevski's opus was popular in his homeland, but I do wonder whether his people were really the movie's primary audience. This isn't a criticism of the film, but just the return of a thought I've had when seeing other reputed landmark films from small countries. It's a suspicion that these countries have more stories to tell than the world sees, for one reason or another. But we probably ought to be grateful for the stories that do get told.

No comments:

Post a Comment