Most movies are made as a corporation product. You know, they're planned, and there's a corporation behind them, and they're turned out. Now what we did is, we made a movie as a military operation. When you have a military operation what happens is you set out to take a given town, and your objective is to take that town, and as you go forward all sorts of unforeseen contingencies arrive, and as they do you go around them, or you go through them, or you go under them. But the whole idea is, in a military operation that you get a certain amount of force, moving, and then you move with it, and you discover what the reality of your attack is by attacking. So what we've been doing in the last five days is making an attack on the nature of reality, on what is reality. You can't say that this is real now, what we're doing; you can't say what we were doing last night is real. The only thing you can say is that the reality exists somewhere in the extraordinary tension between the two extremes of the relationship....

You're still thinking of movies that are made when you very carefully structure them, you follow? And you get the maximum out of each moment. But what I'm arguing about in this method is that you can't make a movie that way and get something even remotely resembling the truth. What you can get is, you can get a unilinear abstract of one man's conception of how something might happen. But what I'm saying is that's not the way anything happens. The way anything happens is that it has five different realities at any given moment which then swing around to there, you see?

Or like this, you follow? And in other words it's sort of a tumbling, odd thing....There's not anyone here, including myself, who finally knows what went on in that movie.

By the standard expressed here Mailer couldn't hope to capture reality in a novel which could only be his own "unilinear abstract." But his operation, as described in a fourth-wall breaking moment near the end of Maidstone, his third feature film, points toward a dead end for modernism at an opposite extreme from art, which to be meaningful must distill experience or "reality" into something comprehensible and ideally vindicated by relevance if not verisimilitude. Mailer's notion of cinema is a recipe for chaos, and Maidstone is a pie in his own face. Something more substantial than a pie, actually.

Mailer apparently conceived Maidstone as a kind of role-playing-game for his cronies, the challenge being whether someone would assassinate Mailer's character, a director turned presidential candidate named Norman T. Kingsley. The author assumes that this Kingsley's candidacy would be taken seriously enough by the power elite that they would contemplate murdering him. We are to understand that Kingsley is an art-house success with a following (of potential voters) in the millions, and a talent comparable to Bunuel, Dreyer, Fellini and Antonioni. The director Norman Mailer isn't the same as the director Kingsley, but from what we see of Kingsley's methods the comparisons are insulting to all of the above. Kingsley's work, which seems to deteriorate from a Bunuel homage to some rather lifeless porn, seems no less amateurish than Mailer's; the latter, it must be said by a fan of the writer, has almost no pictorial sense at all, and at most some aptitude for montage if not narrative. Where there are glimmerings of a visual imagination, Mailer (not Kingsley) seems most influenced by Antonioni in scenes of actors wandering aimlessly through an airy countryside. The wandering may seem Felliniesque, but the space is used more in Antonioni style. But the effect is the opposite of Antonioni's evocation of emptiness, since these excursions feel like idyllic respites from the claustrophobic paranoia chez Kingsley. I'll even give Mailer credit for intending them that way.

Politically, Maidstone is vacuous, its main premise, as far as I can tell, being that Norman Mailer is a legitimate threat to the establishment. Kingsley articulates no political vision, telling a skeptical interviewer only that he has the qualities of character necessary to steer the nation through crises. Mailer sees Kingsley, despite his artistic vocation, as a representative politician, but one guileless enough to allow the contradictions Mailer perceives in all politicians crack the surface -- though while the author sees politicians as potentially part angel, part devil, Kingsley seems mostly devil, a misogynist manipulator who makes an epic ass of himself during an encounter with an ex-wife. With recently-enhanced hindsight, this particular scene, in which actor Mailer scats childishly to some radio music just to fill the air around the estranged couple, reveals Kingsley, if not Mailer, as a real-life Lancaster Dodd, one who we see later admitting that he's made things up as he went along.

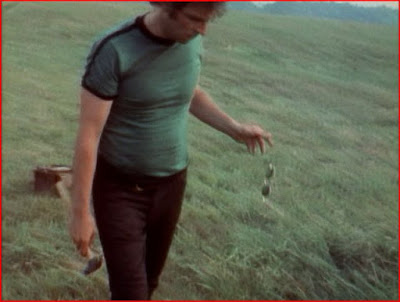

If Mailer/Kingsley is Lancaster Dodd, than Rip Torn, the professional ringer in the cast, is Maidstone's Freddy Quell. Torn doesn't get many opportunities to act extensively, but he's still obviously in another league than all the hopeless participants improvising without method or conviction. In the story or game, Torn plays Kingsley's disgruntled or disturbed brother, the person most likely to be turned into an assassin. Apparently, any assassination attempt was expected at a party Kingsley stages, and during Mailer's Q&A after the fact a cast member expresses surprise that no one tried anything then. But if the rap session was meant to show that the game was over, Torn didn't get the message. Maidstone closes with an apparently spontaneous surprise attack by Torn, in character, on Mailer, with a hammer. A bloodied Mailer instantly falls out of character and fights Torn, who protests that he has to kill Kingsley, not Mailer. After the men are separated by Mailer's legitimately frightened family, they go on arguing as Mailer denounces Torn's betrayal of his trust. Yet Mailer left the attack in the picture, in lieu of an assassination within the game, and may have inserted the Q&A to set up the new ending as a proof of his method, Torn's attack reshaping the reality of Maidstone as an event rather than a narrative. But the wrap-up is more an admission of defeat, a confession that Maidstone could never be anything more than a documentary about itself, less a commentary about anything than raw material for future commentators on Norman Mailer, who had more literary triumphs to come but only one more film to make, the comparatively conventional adaption of his own detective novel, Tough Guys Don't Dance, in the 1980s. Maidstone remains relevant as long as Mailer does, but no matter how much Mailer fascinates me, his ambitions no longer impress many people, -- who expects novels to imitate life now? -- and despite the welcome arrival of three Mailer films in a Criterion Eclipse box set, those films' time is probably running out. But Maidstone seems worth mentioning on the brink of a presidential election, if only to remind you that there are always other candidates than Row A or Row B on the ballot, and some of them are at least more plausible than Kingsley.

No comments:

Post a Comment