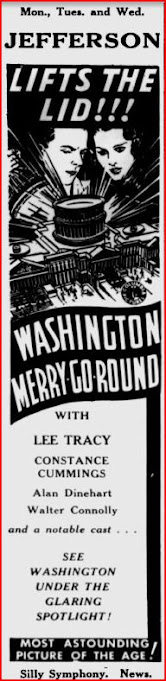

Here's a Columbia picture that seems like it should have been one of studio ace director Frank Capra's films. Capra might have thought so himself, since some of the ideas in James Cruze's picture reappear in Capra's later classics. Cruze directed a screenplay by frequent Capra collaborator Jo Swerling, who worked from a story by playwright Maxwell Anderson, who was inspired by an initially anonymous expose of shady politics in Washington D.C. that evolved into the newspaper column begun by Drew Pearson and continued by Jack Anderson. In many ways the final product looks and feels like a rough draft for a Capra film, but Washington Merry-Go-Round has one of the most stunning moments in Pre-Code cinema, without bare flesh or bullets fired. Freshman congressman Button Gwinett Brown (Lee Tracy) is making his first tour of the nation's capital and taking in a parade of the Bonus Army, the gathering of World War I veterans who demanded an early payment (out of Depression necessity) of the bonuses the government had promised to pay them in 1945, and who were eventually driven out of Washington by tanks at the command of General Douglas MacArthur. Brown, a direct descendant of the Button Gwinett who signed the Declaration of Independence, recognizes an army buddy among the marchers who takes him to see "Bonusville," the veterans' encampment. It's a sad sight and drives Brown to drink a little. His buddy urges him to see some more veterans but Brown tries to beg off. Finally, he makes a little speech -- and turns on them viciously. He reveals his own plan to double-cross his political sponsors by exposing their corruption, then denounces the Bonus Army for being no more than a bunch of panhandlers, more concerned with getting theirs than with helping save the country from the "invisible government" that Brown blames for the nation's plight. More than eighty years later, we've been taught to see the bonus marchers as heroes and victims, and some of them will play a more positive role -- sort of -- later in the picture. But according to Brown -- hence according to Cruze, Swerling, Anderson et al? -- they're part of the problem. In another setting, he complains: everyone comes to Washington to get something, but no one comes to give anything. In Bonusville, he's mobbed out of the camp.

Here's a Columbia picture that seems like it should have been one of studio ace director Frank Capra's films. Capra might have thought so himself, since some of the ideas in James Cruze's picture reappear in Capra's later classics. Cruze directed a screenplay by frequent Capra collaborator Jo Swerling, who worked from a story by playwright Maxwell Anderson, who was inspired by an initially anonymous expose of shady politics in Washington D.C. that evolved into the newspaper column begun by Drew Pearson and continued by Jack Anderson. In many ways the final product looks and feels like a rough draft for a Capra film, but Washington Merry-Go-Round has one of the most stunning moments in Pre-Code cinema, without bare flesh or bullets fired. Freshman congressman Button Gwinett Brown (Lee Tracy) is making his first tour of the nation's capital and taking in a parade of the Bonus Army, the gathering of World War I veterans who demanded an early payment (out of Depression necessity) of the bonuses the government had promised to pay them in 1945, and who were eventually driven out of Washington by tanks at the command of General Douglas MacArthur. Brown, a direct descendant of the Button Gwinett who signed the Declaration of Independence, recognizes an army buddy among the marchers who takes him to see "Bonusville," the veterans' encampment. It's a sad sight and drives Brown to drink a little. His buddy urges him to see some more veterans but Brown tries to beg off. Finally, he makes a little speech -- and turns on them viciously. He reveals his own plan to double-cross his political sponsors by exposing their corruption, then denounces the Bonus Army for being no more than a bunch of panhandlers, more concerned with getting theirs than with helping save the country from the "invisible government" that Brown blames for the nation's plight. More than eighty years later, we've been taught to see the bonus marchers as heroes and victims, and some of them will play a more positive role -- sort of -- later in the picture. But according to Brown -- hence according to Cruze, Swerling, Anderson et al? -- they're part of the problem. In another setting, he complains: everyone comes to Washington to get something, but no one comes to give anything. In Bonusville, he's mobbed out of the camp.What are we supposed to make of Button Gwinett Brown? Embodied by Lee Tracy, he might look like a con man in his own right at first glance. His first scenes are purely comical. His prized possession is an autographed letter from his ancestor, whose signature is the rarest and hence most valuable of all the Declaration's signers. His servant Clarence (Muse, of course) has been allowed to show the letter, valued at $50,000, to a skeptical Pullman porter. In that moment of vindication, a gust of wind on board their train blows the letter out of Clarence's hands. He, Brown and the porter chase after it until it slips under the door into the compartment of Alice Wylie (Constance Cummings), a U.S. Senator's daughter. She mistakes it for trash and tears it up. Informed of her error by Brown, she joins him on the floor gathering up the fragments, both their heads under her bed when her mother enters the compartment. Scandal! We might think we've been introduced to a buffoon, and for much of the picture there's a certain uncertainty about Brown's self-righteousness. He believes in what he's doing, but tends to waste his energy in oratory, including an outburst at the Library of Congress, while regarding the originals of the Declaration and Constitution, that earns unexpected applause from tourists. He wastes his rhetorical firepower on small-time issues, making a laughingstock of himself by taking an epic stand against a $2,000,000 memorial to a Indian-robbing villain of a general. He needs to learn how to advance his agenda pragmatically, find allies, etc. -- but he never gets the chance. Too quick to declare war on the film's villain, a lobbyist-bootlegger who envisions himself a peer of Mussolini and Stalin (Hitler hasn't yet taken power), Brown soon loses his job when the villain arranges for a recount in Brown's district (after his inauguration!) and arranges for Brown to lose. The power of the system is proven again, but it only means that Brown has nothing left to lose, yet plenty to do....

In its final act Washington Merry-Go-Round morphs from often-effective satire to one of the first films in the brief cycle of vigilantism that some viewers ever since have seen as vaguely fascistic. After the villain proves himself irredeemably evil by having old Senator Wylie, Alice's father (Walter Connolly) poisoned, Brown takes decisive action. He's returned to Bonusville, where his buddy has rallied a cohort of dependable men who've seen the justice of Brown's views. They now form Brown's army, taking jobs to spy on the villain and his minions before joining him to stop the villain's car on a lonely road. Brown confronts him with incontestable evidence of his evildoing, but offers him suicide as an easy way out. The film ends with a gunshot in a tent and Brown consoling Alice, his own future uncertain. It's the last of the movie's wild shifts in tone -- it becomes less comical once Muse disappears from the story for no apparent reason, and if the intent was to be critical of Brown's overbearing manner, the ending seems to endorse his uncompromising, ultimately ruthless approach. From satire the film veers into outright fantasy without ever truly cohering due to the chaos at its center. Swerling and Tracy's conception of B. G. Brown might have served Capra as a textbook of what not to do with his own heroes. Capra may have gone too far in making his heroes naive, but it worked better dramatically for his Cinderella-Man heroes to suffer potentially demoralizing learning experiences and grow wiser through endurance than for Brown to arrive in Washington with a master plan in place, already convinced that he's more clever than anyone. That only left me wishing we had seen his campaign and how he must have swallowed his pride while spouting the party line in order to get his big chance in Washington. There's no real learning experience for Brown; adversity only prods him into doubling down and trading constitutionalism for virtual lynch law. The most that can be said for him is that he seems to have been an authentic expression of the confusion and anger of his moment in history.

Washington Merry-Go-Round is an authentically angry and confused film with a few brilliant moments. One of those is Brown and Clarence's arrival in Washington, a busily choreographed sequence involving a convention of Prohibition supporters (the availability of "embassy stuff," i.e. diplomatic liquor, is a running gag), a bunch of Boy Scouts ("Are we gonna see the President?"), a camera-hog fellow congressman, and a lobbyist hired in advance as Brown's secretary but fired by Brown on the spot. The movie may be at its best in such moments of observational humor, but Tracy's vocal firepower is a force not to be denied. Overall it's too inconsistent in tone to be a classic, but it's exactly that anger and confusion that make it an indispensable cinematic document of the era.

2 comments:

Definitely sounds like a movie I need to see.

For anyone interested in the period, regardless of whether you prefer Pre-Code to Classic Hollywood or not, this one's a must.

Post a Comment