Here's an example of Ripperger's ambivalence toward the conflict many saw as a rehearsal for the big war between fascism and its enemies that would break out less than three months from now:

"Something I want to know, comrade," Jose said, "Why you fight for Loyalists? The Frente Popular no interest to you. The C.N.T. -- the Syndicalists, to you they mean nothing. The U.G.T. -- the Socialists, the F.A.I. -- thees Anarchists, all is nothing to you? Why you fight for us? Why you fight so brave, like a man crazy?"

Graham rolled a cigarette. He didn't quite know how to answer that.

"I don't know what's right or wrong over there, Jose," he said, "It just sort of happened. I was up there in Madrid when the war started. I joined up because things were so bad in Madrid, so much confusion, so much muddling, so many lives lost that shouldn't have been lost and before I knew it, the thing that I was fighting for suddenly seemed bigger than I was. I didn't stop to think."

The fanatic light in Jose's eyes changed. "You don't believe in thees thing, comrade?" he said sadly.

"I don't know, Jose. Sometimes I think that everything you believe is right and sometimes I don't. I've seen things done....Well, I don't know."

"In war -- in war, sometimes you have to do things not so nice."

This ambivalence should prove a redeeming quality should the plot develop in conventional ways. One wonders how well informed Ripperger was about the war. The Fiction Mags index has no biographical information about him, so I did a quick investigation of my own. Ripperger (1889-1944) was a businessman, mainly as a treasurer and director of the Tech-Art Plastics Company. Writing was a family hobby; Ripperger's wife published in women's magazines while two daughters collaborated on fiction under a single pseudonym. During World War II, before his death, Ripperger chaired the Brooklyn Red Cross's blood donor service. In the writing business, he may be most noteworthy for publishing a two-part adaptation of King Kong in Mystery Magazine during the film's initial release. His 1941 novella "I'll Buy Your Life" was turned into a Poverty Row movie called I'll Sell Your Life that same year. Not bad for a dilletante, I suppose.

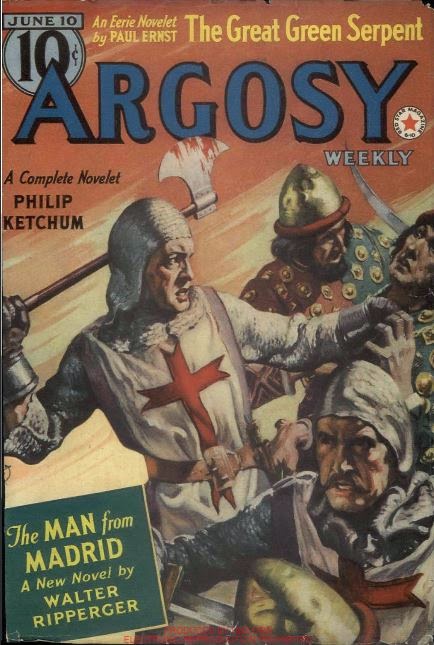

This week's cover feature is the latest story in Philip Ketchum's chronicle of Bretwalda, the charmed battle-axe tied to the destiny of Britain. "Delay at Antioch" takes us far from Bretwalda's usual sphere of influence, following its latest wielder on the First Crusade to the besieged title city. The axe doesn't really have or confer super powers on its wielders. The fated family members can wield it with ease while few others can, but that's about it apart from the doom that brings both victory and defeat, great joy and great sorrow, to each generation. For the latest generation, that means a star-crossed love with a Muslim princess whose inevitable death --even though she's half-Armenian, their mating might have smacked too much of race-mixing for some readers -- tempers our hero's enthusiasm over the eventual fall of the great city. Ketchum writes heroic action reasonably well but is less gung ho about the Crusade idea than Robert Carse was in retrospect a few weeks ago, For Carse the Crusades were a metaphor for a war to come, while Ketchum, working on a tragic theme, can't work up as much idealism about the conquest of the Holy Land. His Muslims are adversaries rather than villains, the real bad guy being a rival Crusader who tries to kill our hero but ends up eliminating the princess instead. Ketchum wrote at a time when many, in the west at least, saw the Crusades as a kind of chivalrous war with heroes on both sides, Saladin being the exemplary antihero of that myth. Cecil B. DeMille made a Crusades movie a few years earlier (co-written by pulp superstar Harold Lamb) and an Egyptian government remembered it so well and favorably twenty years later that they welcomed him to film The Ten Commandments on location. Ketchum's Crusade story catches some of that same attitude.

The other major stand-alone story this week is Paul Ernst's "The Great Green Serpent," which reads as if it had been rejected by Weird Tales. It even has the sort of in-joke references to other authors I associate with the Lovecraft circle (not knowing if Ernst really was one of them) -- the protagonist visits a Dr. Belknap of Longview Hospital, who has got to be a nod to or dig at Frank Belknap Long for some reason or other. It's the story of a Jamaican voodoo curse and how it destroys an American plantation boss who kills a witch-doctor, and apparently will destroy the narrator investigating the original victim's fate. The extra gimmick is that the victim's picture can't be taken, while his touch causes matches to ignite. One thing I'll say for Ernst: this story does have a great final sentence, giving us the twist in the tale we may have expected all along at the last possible moment. The other stand-alones are W. Donaldson Smith's "Home Are the Horses," about a self-destructive jockey, and Luke Short's "Some Dogs Steal," a comical tall tale about the havoc wrought on trappers by one such incorrigible cur. Hugh B. Cave's "Boomerang" counts as an "Argosy Oddity," which isn't very flattering on the editor's part; this three-pager deals with poison and revenge in a familiar manner.

On the serial front, John Stromberg's "Wild River" builds up to next week's conclusion in strange fashion as our hero takes his communist pal on a vacation to visit his crusty old rancher grandfather. How this confrontation of ruggedest individualism and aggrieved collectivism will turn out seems to matter more than whether our hero will ever get a decent job on the Boulder Dam project, but this has been an unorthodox serial all along, and not really in a bad way. Howard Rigsby's "Voyage to Leandro" goes into survival mode in its second installment as our two teenage seaborne runaways realize that they might be short on supplies for their trek to the South Sea Islands, then shipwreck on a desert isle that proves not entirely deserted. In fact, the notorious mutineer who had been their idol is holed up there as well, but now he seems more like a threat, which is a nice way to keep the story interesting. They and the Man From Madrid will be back next week, while the main attraction then will be the return of Tomorrow, i.e. Arthur Leo Zagat's bunch of postapocalyptic cave-kids embarking on a quixotic quest to liberate the U.S. from the Non-White Peril. War is coming in 1939, and it'll be in Argosy first!

TO BE CONTINUED

No comments:

Post a Comment