While he suffered for reporting on the illegal casino, Lee realizes that the mob suffered more from the publicity. Louis Blanco (Gable) generously explains to him that he can parlay this journalistic coup into a long-term racket. Powerful people will pay him to keep damaging news out of the newspaper. Actually they'll pay Louis Blanco, but Lee's cut will make him rich compared to his chicken-feed newspaper salary. Those who don't play ball will get exposed, reinforcing Lee's rep as an anti-crime crusader. He justifies his position to his girlfriend (Fay Wray) by portraying himself as preying on society's predators -- who actually suffers from that?

Inevitably power goes to Lee's head. He starts to go over Blanco's head to make deals and threats. Finally he's summoned into the presence of "Number One," the unnamed underworld overlord who warns him against reporting on another casino opening. Number One gets the old presidential treatment; we never see his face, and this deliberate omission can only mean that he's meant to be Al Capone, then still ruling Chicago crime. Unintimidated, Lee negotiates a $100,000 bribe but is warned that he'll be held responsible if anyone publishes a story about the Casino in his paper. To justify the title of the picture, Number One says that the finger will be pointing at Lee, and Dillon gives us a close-up of the gangster's finger to drive the point home. So of course Lee's co-worker Breezy (Regis Toomey), a rival both for stories and for Fay Wray, manages to crack the casino story on his own and gets a front-page story while Lee is making love to his girl. From this point the film doesn't even pretend to maintain suspense. Our hero is just plain doomed, and finally gets riddled with bullets in broad daylight on a busy street. With only Fay and the gangsters knowing the truth, Breckinridge Lee gets a hero's funeral to end the film on a grimly ironic note.

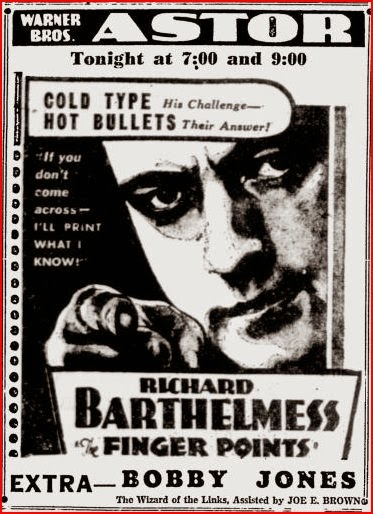

The Finger Points is another reminder of how dependent the Warners gangster genre was on the charismatic authenticity of Edward G. Robinson and James Cagney. By comparison, Clark Gable, while persuasive as a thuggish chauffeur in Warners' Night Nurse, hardly makes an impression as this film's primary gangster. He just doesn't seem like a "Louis Blanco," and in any event he has to take a back seat to the problematic Richard Barthelmess. Warners struggled with the silent idol they inherited from First National for several years of sound. His lilting accent seems, however unfairly, to have undermined his he-man pretensions. A southern drawl made Una Merkel cute but that may have been Barthelmess's weakness -- maybe his southern accent made him too cute for his own good. Voice aside, Barthelmess lacks the aggression that defined Warner Bros., as embodied not only by Cagney and Robinson but a small army of gold diggers in the studio stock company. The studio knew better, it seems, than to cast him as an actual gangster, but he isn't even very convincing as a corrupt reporter. The actor seems more out of his depth than the character he's playing is supposed to be. It may be telling that his best performance for Warners in the sound era, in William Wellman's Heroes For Sale, is one in which he plays an epic victim. Barthelmess and Gable's awkwardness in their roles keeps Finger Points out of the gangster-cinema canon despite a story that deserved better.

No comments:

Post a Comment