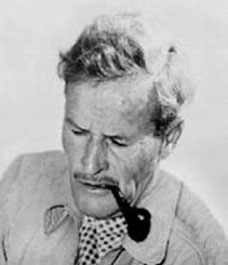

Warner Home Video's "Forbidden Hollywood Vol. 3" collection by all rights should be called The William A. Wellman Collection, but it's not such a sad fact that "Forbidden Hollywood" (i.e. "pre-Code" cinema) is a more bankable label than Wellman's name. Three volumes means there's a market for the pre-Code stuff, which is good news for anyone interested in seeing the major studios push the envelope during the early 1930s. But for whatever reason, the new set focuses exclusively on Wellman, including two documentaries on the man.

Warner Home Video's "Forbidden Hollywood Vol. 3" collection by all rights should be called The William A. Wellman Collection, but it's not such a sad fact that "Forbidden Hollywood" (i.e. "pre-Code" cinema) is a more bankable label than Wellman's name. Three volumes means there's a market for the pre-Code stuff, which is good news for anyone interested in seeing the major studios push the envelope during the early 1930s. But for whatever reason, the new set focuses exclusively on Wellman, including two documentaries on the man.How's this for a reason: from 1931 through 1933, Wellman was on fire at Warner Bros. He's credited with seventeen feature films over this three-year period, along with substantial uncredited work on an eighteenth production. His best know work is the epochal gangster film The Public Enemy, which was James Cagney's ticket to stardom. Wellman gave a preview of what he could do with Cagney in Other Men's Women, which I saw on TCM last night as part of the channel's admirable but perhaps counterproductive airing of all the films (and one of the documentaries) in the new collection. Cagney is fourth-billed for a tangential role in this hokey romantic triangle, but Wellman gives him two awesome entrance scenes, one walking on top of a moving train, the other arriving at a dance hall, stripping off his soaking work clothes to reveal evening clothes underneath, and dancing his girlfriend onto the dance floor. After those you're supposed to care whether Regis Toomey or Grant Withers gets Mary Astor? But never mind them: the film itself is a delight to watch for its grungy social realism and a terrific climax involving driving rains and floods, trains on a shaky bridge, and a blind man trying to remember his way across the dark, wet tracks.

Wellman dug rain and he dug trains. Trains are a major feature of his furious Depression expose, Wild Boys of the Road. This 1933 effort follows teenage boys and girls on the bum because their parents can't support them anymore, forming small armies of tramps who prove quite capable of organizing themselves, whether to start a self-governing community made of giant industrial pipes, fight off smaller armies of club-wielding railroad detectives, or lynch a rapist played by Ward Bond. Wild Boys is a relic of that utopian time when a major Hollywood studio would focus on the struggles of working class people (criminal or not) almost as a house style. The film ends up as political propaganda for the New Deal as a judge with an NRA (not the rifle association) sign behind his chair tells our protagonists that things are going to get better now, but Wellman and Warners are unafraid of saying that things stink pretty bad right this instant.

The other film I watched (curse me for lacking DVR with nothing but laziness to blame!) was an odd Barbara Stanwyck vehicle, The Purchase Price. Wellman goes out on location to simulate rural Canada for this story of a torch singer who hires out as something like a mail-order bride in order to avoid an overbearing gangster boyfriend. The main pre-Code element of this one is seeing Stanwyck in her undies, but the main entertainment value is in its portrait of rustic barbarism north of the border. George Brent is a dork of a leading man redeemed by the revelation of his college degree and his innovations in wheat cultivation, but he does have a nice fight scene with Lyle Talbot near the end. Brent and Stanwyck spend the film sending mixed signals to one another, but there's enough else going on to make Purchase Price worth at least a look.

These movies are called "Forbidden Hollywood" because some of their contents would soon be forbidden once serious Code enforcement kicked in after 1934. You wouldn't be likely to hear Joan Blondell call herself a member of the APO ("Ain't Puttin' Out") for a long while afterward, for instance. But I was left wondering whether some of the subject matter might still be forbidden from major studio products, or more forbidden than it was seventy years ago.

No comments:

Post a Comment