Meet a different kind of femme fatale. Sheila Bennett (Evelyn Keyes) is "the blonde death," a diamond smuggler on a mission in New York City. The mission is revenge. She brought the hot diamonds from Cuba for her husband, Matt Krane (Charles Korvin), not knowing that the rat has been two-timing her with her own sister (Lola Albright). She's arranged to have the rocks delivered discreetly by mail to her impatient lover-boy, but he takes advantage of her apparent illness to take the diamonds and run without telling her they'd arrived. She learns from Willy, a sleazy nightclub owner (Jim Backus) about her boyfriend's cheating. After confronting her sister, she goes to a sympathetic fence to learn that hubby's still holding the diamonds, which were too hot to unload because the feds had followed Sheila into the city. He told Matt to come back in ten days, so if Sheila can wait it out she can have it out with her husband. It's more than sister Francie can do; she killed herself in a fit of guilt while Sheila was out. It's just something else Matt will have to answer for, if only Sheila can stick out those ten days. It won't be as easy as it sounds, because Sheila brought something back from Cuba besides diamonds -- smallpox.

Meet a different kind of femme fatale. Sheila Bennett (Evelyn Keyes) is "the blonde death," a diamond smuggler on a mission in New York City. The mission is revenge. She brought the hot diamonds from Cuba for her husband, Matt Krane (Charles Korvin), not knowing that the rat has been two-timing her with her own sister (Lola Albright). She's arranged to have the rocks delivered discreetly by mail to her impatient lover-boy, but he takes advantage of her apparent illness to take the diamonds and run without telling her they'd arrived. She learns from Willy, a sleazy nightclub owner (Jim Backus) about her boyfriend's cheating. After confronting her sister, she goes to a sympathetic fence to learn that hubby's still holding the diamonds, which were too hot to unload because the feds had followed Sheila into the city. He told Matt to come back in ten days, so if Sheila can wait it out she can have it out with her husband. It's more than sister Francie can do; she killed herself in a fit of guilt while Sheila was out. It's just something else Matt will have to answer for, if only Sheila can stick out those ten days. It won't be as easy as it sounds, because Sheila brought something back from Cuba besides diamonds -- smallpox. Sheila is soon the subject of two separate manhunts. First, the feds are still after her for diamond smuggling, but their investigation is handicapped by their lack of a photo image of her. Why the agent who followed her back from Cuba couldn't sit down with a sketch artist at any point in the pursuit is an unsolved mystery of this picture. But at least they have the memory of a face to work with. The doctors who discover a smallpox outbreak don't even have that. They only get clues to the carrier's identity as more people get sick. Ironically, the doctor leading the hunt (William Bishop) saw Sheila in his clinic the night she arrived in the city. At the time, "Agnes Dean" was only complaining of headache and weakness. Dr. Wood hands her a bottle of "medicine" off the shelf and tells her to use it regularly. Whatever this medicine is, it must be a wonder drug, because it keeps Sheila careening through Manhattan in search of clues about Matt well beyond a point when a normal smallpox victim, we're told, would be flat on her back, or dead. On the other hand, this amazing medicine may have been no more than a placebo, since we're also told that "drive" can make cripples walk, or make the sick keep walking.

Sheila is soon the subject of two separate manhunts. First, the feds are still after her for diamond smuggling, but their investigation is handicapped by their lack of a photo image of her. Why the agent who followed her back from Cuba couldn't sit down with a sketch artist at any point in the pursuit is an unsolved mystery of this picture. But at least they have the memory of a face to work with. The doctors who discover a smallpox outbreak don't even have that. They only get clues to the carrier's identity as more people get sick. Ironically, the doctor leading the hunt (William Bishop) saw Sheila in his clinic the night she arrived in the city. At the time, "Agnes Dean" was only complaining of headache and weakness. Dr. Wood hands her a bottle of "medicine" off the shelf and tells her to use it regularly. Whatever this medicine is, it must be a wonder drug, because it keeps Sheila careening through Manhattan in search of clues about Matt well beyond a point when a normal smallpox victim, we're told, would be flat on her back, or dead. On the other hand, this amazing medicine may have been no more than a placebo, since we're also told that "drive" can make cripples walk, or make the sick keep walking.While she moves from place to place, just keeping ahead of the feds over the ten days until Matt returns, New York City is mobilized to vaccinate as many people as possible as more of those whose paths she crossed start dropping: a Penn Station porter; a little girl in Dr. Wood's clinic; Willy the nightclub owner, and so on. Vaccine supplies are limited, since hardly anyone anticipated a smallpox outbreak in the U.S.A., so as long as Sheila runs free, thousands if not millions of lives are in danger.Men: They'll pay in different ways for messing with the Blonde Death.

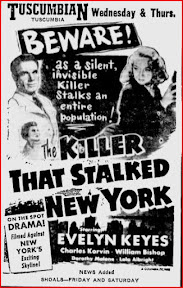

A remarkable piece of title-card art for The Killer That Stalked New York.

This slick Columbia B picture is clearly hoping that two great tastes will taste great together: the medical-procedural thriller a la Panic in the Streets and the mortally-doomed protagonist of D.O.A. It has many of the major film noir trappings, including impressive location shooting in New York by Joseph Biroc and, regrettably, an omniscient narrator who speaks in the first person but never becomes a character in the story. The narrator (Reed Hadley) lays the rhetoric on real thick during the first few minutes, but his presence becomes thankfully more intermittent afterwards. Loosely inspired by a real-life smallpox scare, the story often lapses into agitprop for immunization, and I have to admit I was ruefully amused by scenes of paranoid skeptics protesting against the shots when I know that people like that still exist in this country.

Evelyn Keyes stands out in a mostly-competent cast that includes a young Dorothy Malone as a nurse and future teenage monster maker Whit Bissel as Sheila's flophouse-operating brother. Keyes bravely submits to the deglamorizing effects of smallpox and effectively portrays a woman betrayed by family and fate alike, as well as the obsessive drive that animates many a noir hero or antihero.

Earl McEvoy directed only three features, this being his second, after serving time as an assistant director at M-G-M. He's no great stylist on this evidence, but he makes good use of the locations on several occasions, particularly two sweeping shots, one at Penn Station, showing one character watching another from high above and far away. Harry Essex's script credits range from Man-Made Monster to The Sons of Katie Elder, but this time there are too many story-prolonging contrivances (the incompetent feds, the miracle medicine) for it to be one of his finest hours. But while logic may have made the story shorter, the film still comes in at a lean 75 minutes and is never dull. The location work and Biroc's cinematography as a whole make The Killer That Stalked New York at least worth looking at, and Keyes's performance is definitely one worth watching.

Earl McEvoy directed only three features, this being his second, after serving time as an assistant director at M-G-M. He's no great stylist on this evidence, but he makes good use of the locations on several occasions, particularly two sweeping shots, one at Penn Station, showing one character watching another from high above and far away. Harry Essex's script credits range from Man-Made Monster to The Sons of Katie Elder, but this time there are too many story-prolonging contrivances (the incompetent feds, the miracle medicine) for it to be one of his finest hours. But while logic may have made the story shorter, the film still comes in at a lean 75 minutes and is never dull. The location work and Biroc's cinematography as a whole make The Killer That Stalked New York at least worth looking at, and Keyes's performance is definitely one worth watching.This is one of four films in Bad Girls of Film Noir, Volume 1, another extraordinary release from Sony Pictures Home Entertainment in defiance of industry trends. Each film (the others are Henry Levin's Two of a Kind (1951), Irving Rapper's Bad For Each Other (1953) and Maxwell Shane's The Glass Wall comes with a theatrical trailer, while Two of a Kind is supplemented by an interview with co-star Terry Moore, and the set as a whole comes with a presumably noirish episode of the All-Star Theater TV series. Volume 2, similar equipped, is already available. These are priced comparably with Sony's Icons sets of Hammer and Toho films, a relief after the company's somewhat overpriced Film Noir set and it's way overpriced Samuel Fuller collection. I'll let you know about the rest of the films as I see them. They may be B movies, but I'm hoping for the best.

Here's the trailer, courtesy of TCM:

4 comments:

Another movie with a similar theme that is well worth checking out is 80,000 Suspects, a British movie from 1963. It was directed by Val Guest, who did the early Quatermass films for Hammer.

Not seen this but yes, 80,000 Suspects is cool.

Samuel,

This is an enjoyable B movie with no pretensions, and as you mention Keyes is the standout here, (I also liked her in ACT OF VIOLENCE). The New York locations help the film tremendously and I remember the bit about people being resistant to taking a vaccine that shows the more things change, the more they stay the same.

d., Sarah: Thanks for the tip on 80,000 Suspects. I'll have to catch up with that if it can be seen in America.

John: I don't think they could have sold the city-in-peril concept without having Keyes running around in the actual city. McEvoy got some very nice shots of her against the cityscape. No one seems to know much about him, as far as I can tell. I don't know if he dropped out of the business due to health problems (he died in 1959), was blacklisted, or just fell out of favor. Does anyone?

Post a Comment