The book interested me because I had seen the movie, first in fleeting glances on AMC, then in full on DVD. Edward Dmytryk's film impressed me as one of the superior "adult" westerns that Hollywood cranked out during the 1950s. What I liked about it was the emergence of Richard Widmark's reformed outlaw as the real hero of the story, in ultimate opposition to Henry Fonda's Earp-like super gunfighter. I also enjoyed the variations on the Wyatt Earp-Doc Holliday archetype played out by Fonda and Anthony Quinn, and I was pleasantly surprised by a DeForest Kelley supporting turn that nearly steals the picture at times. The novel was recently reissued by the NYRB Press, sporting a blurb from no less a literary personage than Thomas Pynchon, but I guessed that I could find a used copy for less. I finished the book over the weekend and decided to look at the movie again for the sake of comparison.

Warlock is primarily the story of John "Bud" Gannon, a former member of Abe McQuown's San Pablo cowboy gang and his repudiation of their outlaw ways. Neither fully trusted by the townspeople of Warlock nor any longer respected by most of the cowboys, including his brother Billy, Gannon becomes a deputy sheriff, the highest ranking law enforcement official the town can have. This makes him a theoretical ally and eventual rival of Clay Blaisedell, a famous gunfighter hired by a citizens' committee to act as marshall and crack down on the McQuown gang. Blaisedell is accompanied by Tom Morgan, a gambler and fellow gunfighter who seems a less principled figure. Morgan shows his true colors by killing a man on the way into town and letting some cowboys (who coincidentally were in the process of robbing the stage the man was riding in) take the blame for it. Morgan had guessed that the man was coming with his and Blaisedell's nemesis, Kate Dollar, to kill Clay in revenge for his earlier killing of Kate's fiancee. As suspicions of his involvement spread through town, Morgan becomes impatient for Clay to leave town with him, but Blaisedell has fallen for the "miners' angel," Jessie Marlow and begun to think of settling down. The defeat of McQuown's cowboys is only the prelude to two climactic confrontations, Morgan against Blaisedell and Blaisedell against Gannon.

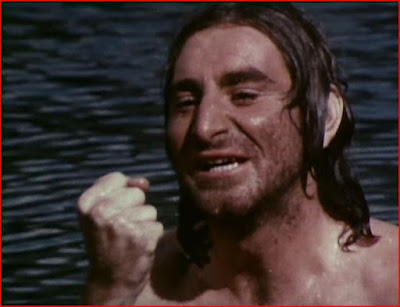

Warlock is primarily the story of John "Bud" Gannon, a former member of Abe McQuown's San Pablo cowboy gang and his repudiation of their outlaw ways. Neither fully trusted by the townspeople of Warlock nor any longer respected by most of the cowboys, including his brother Billy, Gannon becomes a deputy sheriff, the highest ranking law enforcement official the town can have. This makes him a theoretical ally and eventual rival of Clay Blaisedell, a famous gunfighter hired by a citizens' committee to act as marshall and crack down on the McQuown gang. Blaisedell is accompanied by Tom Morgan, a gambler and fellow gunfighter who seems a less principled figure. Morgan shows his true colors by killing a man on the way into town and letting some cowboys (who coincidentally were in the process of robbing the stage the man was riding in) take the blame for it. Morgan had guessed that the man was coming with his and Blaisedell's nemesis, Kate Dollar, to kill Clay in revenge for his earlier killing of Kate's fiancee. As suspicions of his involvement spread through town, Morgan becomes impatient for Clay to leave town with him, but Blaisedell has fallen for the "miners' angel," Jessie Marlow and begun to think of settling down. The defeat of McQuown's cowboys is only the prelude to two climactic confrontations, Morgan against Blaisedell and Blaisedell against Gannon.Henry Fonda as Blaisedell and Anthony Quinn as Morgan in Edward Dmytryk's

Warlock

The novel weighs in at abut 450 pages in modest-sized type, while the film just makes it over the two-hour mark. Inevitably, producer-director Dmytryk and writer Robert Alan Arthur had to cut things. What they cut was the middle of the novel, a long section dealing with the repercussions in town of a bitter miners' strike. Warlock is episodic enough in structure that doing this does not render the climax incoherent. But because the novel develops as a kind of slow burn toward the ultimate showdowns, the movie has to simplify things a bit. Important characters from the novel, like the violently senile territorial governor, General Peach, are eliminated. Others, like Dr. Wagner, who is a rival of Blaisedell's for Jessie's affections as well as a leader of the miners' strike in the novel, are reduced to insignificance.

Dmytryk and Arthur have to exaggerate Morgan's personality in order to condense his crucial character arc. If you've read any commentary on Warlock, you've probably seen it said that Morgan, at least as interpreted by Anthony Quinn, has some sort of homoerotic feeling toward Blaisdell. The film really gives you more cause to think this than the book, which isn't to say that the novel gives none, by making Morgan more dandyish and yet more grotesque. Quinn is burdened with a limp that Morgan does without in the novel, and in the film he is made to say, in explaining his intense friendship with Blaisedell, that Clay is"the only person, man or woman, who looked at me and didn't see a cripple." Compared to the novel, this is out of the Lon Chaney Sr. school of characterization. The movie Morgan is also inclined to quote Shakespeare and is more interested in the interior design of his gambling hell than the movie would have you think is strictly manly.

But in the book the key to the gunmen's friendship is Morgan's claim that he alone accepts Clay Blaisedell for what he is rather than expecting him to play some kind of role as hero, lawman, etc. However, the question of what Blaisedell is hangs over the whole novel. Clay is only ever seen from the outside, from the viewpoints of Morgan, Jessie, Kate, Gannon and the running commentary of Henry Holmes Goodpasture's journal. Blaisedell is meant to be an enigma, perhaps even a human void, but a movie character can't be the same kind of enigma. On the screen we can't get into some characters' heads and not others unless the producers opt for voiceovers. Instead, Dmytryk and Arthur try to flesh out Blaisedell's character in order to give Henry Fonda more to do than be godlike. The movie Clay ends up being a more righteous and moralizing man than the original, quicker to come into conflict with Morgan. He also ends up more of a tragic figure, since we know his desires for domesticity and retirement, while we never really know them as certainly in the novel.

But while there's a lot of tweaking of Morgan's character, including messing with his motivations toward the end, Blaisedell ends the story exactly as he does in the book. In the film, Morgan becomes irrationally hostile to Gannon, goading Clay to kill him and threatening to do it himself. This is because Gannon's success as deputy seems to threaten Blaisedell's heroic public standing. Movie Morgan says Clay must destroy Gannon to reassert his dominance, since "if you're not the marshal you're nothing." Quinn is threatening to kill Gannon when Blaisedell meets him for their fatal showdown. But in the novel Morgan has actually locked Gannon in his own jail so the deputy won't risk his life interfering in his intended suicide-by-Clay. He protects Gannon to fulfill a promise to Kate Dollar (called Lily in the movie for no good reason), who has fallen for the deputy. At the same time, Morgan has decided to destroy himself as a last resort to give Clay an opportunity to settle down with Jessie. He was jealous of her earlier in the story but ends up convinced that she, like him, can accept Clay as he is. Morgan originally meant only to provoke Blaisedell into driving him out of town, since he was planning to leave anyway, so that Clay would be able to retire as a hero if he chose. But Blaisedell wouldn't rise to the bait the first time around, even though murder was involved, so Morgan felt forced to raise the stakes. The movie offers a very simplified version of Morgan's thinking, as Quinn decides to sacrifice himself in order to re-establish Blaisedell as an "important" person, and dies declaring "I win."

But Blaisedell's reaction shows that neither Morgan nor Jesse nor anyone else had won. In book and movie alike, he goes berserk with grieving rage, forcing the townspeople to do homage to Morgan's body, kicking the crutch out from under self-righteous Judge Holloway, and finally burning the saloon down over the corpse in a sort of landlocked Viking funeral. If Quinn's performance gives viewers cause to wonder about Morgan's sexuality, this hellacious sequence (marred only by an apparent budget shortfall that prevented Dmytryk showing a full-scale fire) should make people wonder about Blaisedell.

"I win."

John Gannon starts the novel already separated from the McQuown gang. He comes into Warlock on his own looking for work, and it's explained early that he quit the cowboys because of a massacre of Mexicans they took part in. That event is referenced in the movie, but the film starts with Gannon still part of the gang, albeit clearly feeling alienated. He trails behind the rest whenever they ride into town. The massacre weighs on him, he reveals later, but for movie purposes his breaking point with the cowboys comes when he prevents his personal enemy Jack Cade from backshooting Blaisedell during a standoff between the marshall and the sardonic Curley Burne. Seeing that Abe McQuown condoned the attempted treachery, Gannon decides to stay in Warlock, eventually becoming the deputy.

Gannon and Blaisedell stand for opposing ideas of law and order. Blaisedell embodies order maintained by force and charisma, while Gannon, following his moral epiphany, clings doggedly to the idea of a rule of law. In the novel, Gannon is frequently denounced by his former friends and by others who see him as "cold." This is because he has come to put the law above personal ties. Abe McQuown hearkens back to a time when no one needed the law because people had friends to back them up in any scrape. Gannon seems to point toward a modern day when people can function as individuals without depending on kin or gang membership. He represents a new kind of honor, opposed to an older code that seems tied to an implicit death wish. In the novel, Gannon speculates that bad men often get themselves recklessly into gunfights as a way of inviting punishment for themselves, and Hall gives examples throughout the story (including Morgan) that hint that Gannon is right. This seems to explain why so many men feel compelled to challenge Blaisedell, especially when he posts them out of town. Gannon himself doesn't presume to post people that way, though he finally finds himself forced to with Blaisedell himself. The outcome seems to vindicate Gannon's ethical vision, but the novel and the movie actually come to different conclusions.

While Gannon's integrity is the core of the story in both versions, the movie portrays Gannon's triumph less as a victory for individual conscience than as a victory for the town as a whole. Blaisedell also looks forward to the day when Warlock won't need him, and in an optimistic moment in the film Fonda says, "It looks like Warlock's growing up." The movie holds up an idea of settlement and domesticity that the novel never quite endorses. It renders Blaisedell a tragic character because he finally can't settle down and become a husband and father. He becomes an equivalent to Ethan Edwards in The Searchers standing outside the closing door, or John Wayne's character in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance: a violent man who is necessary for one moment of history but unfit for the next stage. The movie leaves you with a sense of certainty that Warlock will go on without him.

Oakley Hall closes the novel with a disillusioning epilogue in the form of a letter written in 1924, more than 40 years after the main events. In this short coda, Henry Holmes Goodpasture explains that Warlock became a ghost town not long after the story following the failure of the mining industry. The town died, but not before John Gannon, shot in the back by his arch-enemy Jack Cade -- a character Gannon kills in the movie. This was clearly more than the producers thought moviegoers of 1959 could take, so the film leaves us in a moment of tragic optimism, the apparent triumph of civilization counting for more than Jessie's unhappiness or Clay's journey to likely oblivion.

So as is often the case, a movie adaptation looks wanting after you've read the source novel. But let me stop the criticism to say that Dmytryk's Warlock is still an excellent film and one of the best of the mature 50s westerns from the pre-spaghetti peak of the genre. From location work to art direction it is a "mighty" film, as the paperback promises.

It's also one of the best ensemble casts you'll ever see in a western. Having Fonda, Quinn and Widmark together rather guarantees mightiness, and Dorothy Malone is also formidable as Lily Dollar, though perhaps less than Kate Dollar should have been. The fifth above-the-title player, Dolores Michaels as Jessie, doesn't quite hold up her end, but that character is very much underwritten compared to the book. On the other hand, it's time to give props to DeForest Kelley for what's probably his finest cinematic hour playing Curley Burne.

We like to think of Kelley as a doctor, not an actor, but some people are qualified for certain genres, and Kelley seems to have been meant for westerns. Curley is a clown with a little bit of unflappable crazy courage. He's unafraid to taunt Blaisedell several times over, but his sense of humor seems to be linked to a fundamental though much submerged moral sense that finally prevails when he saves Gannon from being backshot during a showdown. In the novel, Curley Burne accidentally kills a man, gets posted out of town by Blaisedell, and gets killed challenging the marshall in one of those encounters that look a lot like suicide to Gannon. I like to think that Dmytryk saw what Kelley was doing with the role and decided not just to spare Burne but turn him into a good guy at the end.

Warlock also boasts one of my favorite scenes in any western. A highlight of both book and movie is the attempted lynching of the cowboys (including an unbilled Frank Gorshin as Billy Gannon) accused of the stagecoach murder. Blaisedell takes command of the scene in an awesome moment when he basically commands a ringleader of the mob to step forward and get clubbed on the head with a gun butt. It's a great moment on film but even greater in the novel when, after already clubbing one man down in a melee, Blaisedell orders a second man to step up and get clobbered. He is obeyed. But even what we get on film is awesome.

Then again, I thought it was awesome when Blaisedell knocked down the judge and made him crawl out of the saloon. If anything, the scene is more hardcore in the movie, in which the judge is merely a self-righteous blowhard rather than an often-pathetic yet sometimes astute drunkard who might be thought to have it coming. Fonda is required to be benign in more romantic scenes but at his best here he is fearsome in what was probably an unwitting audition for Once Upon A Time in the West.

I recommend both the book and the film to anyone who likes westerns or the actors involved. My advice is to watch the movie first. After that, reading the novel is like a "director's cut" full of deleted and expanded scenes that enrich the story. Once you've done both, you'll want to give the filmmakers credit, despite my criticisms, for getting so much of the essential story right.