Let's take a closer look at some of these.

Duck Soup is most likely the most beloved today of these films, and maybe the runner-up to King Kong in the posterity popularity contest. In legend Leo McCarey's picture was a flop and left the Marxes without a studio home until Irving Thalberg saved them at the cost of their edge. While it's not the biggest attraction for New Year's audiences in Milwaukee, at least if you measure by column inches, it's clearly a big one.

If the Christmas attractions were mainly single-star vehicles, for New Years Milwaukee's theaters went for the opposite approach, as exemplified by George Cukor's all-star comedy for M-G-M. Moderns might wonder at Marie Dressler's top billing but the old lady probably was the most popular star of those cast here. One might notice a slowing of Lee Tracy's momentum from earlier in the year, when we saw him top-billed in several comedies, since he only makes the second tier of stars here. His misadventures while filming Viva Villa! in Mexico marked a turning point that soon reduced the gabby actor to B stardom at best and character roles in later life.

RKO was still looking for an answer to Warner Bros.' new style of musical pictures, and this was their latest experiment. The emphasis is on spectacle on a nearly cartoonish scale, the money shot being the "bevy of singing, dancing beauties atop an armada of airplanes!" But the studio had some not-so-secret weapons with more staying power. Note how the ad tries to sell the Carioca as a new dance craze, without really identifying it with the couple who introduce it in the picture. There was some flexibility about the billing, as you can tell by comparing the ad above with the ad on the left. Dolores Del Rio is consistently the top banana, but the order rotates underneath. Fred Astaire, whose first major film showcase this is, bounces between second billing and fifth, in one instance ahead of his dance partner, the already-established film star (and veteran of the Warners spectacles) Ginger Rogers, in another beneath her. In retrospect, the way RKO learned to use Rogers, compared to how Warners did, is as significant as how they used Astaire. Rogers's best-known moment in a Warners musical is her rendition of "We're In the Money" in Gold Diggers of 1933, but her singing is inevitably overshadowed by the Busby Berkeley spectacle surrounding her. By emphasizing her virtuosity as a dancer as well as a singer, RKO made her, with Astaire, the spectacle itself. By focusing on virtuosity rather than the spectacle of sheer numbers, the studio found the answer to Berkely and Warners after several false starts. RKO's earlier comic musicals are so cartoonish at points that they border on the inhuman; they do little to endear themselves to posterity, unless you're a connoisseur of Pre-Code strangeness like me. With Astaire and Rogers, RKO would usher in the classical period of the Hollywood musical.

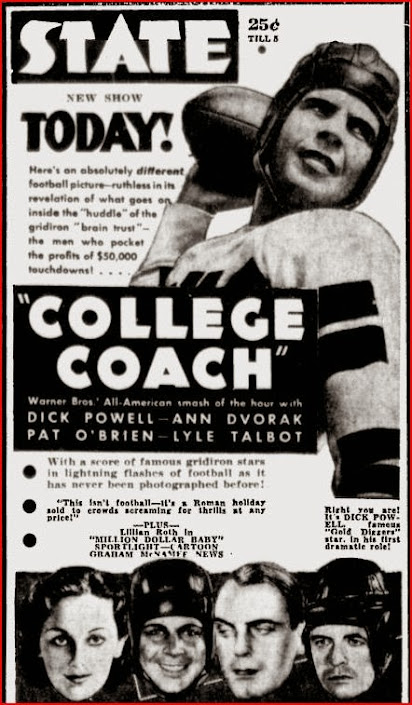

RKO was still looking for an answer to Warner Bros.' new style of musical pictures, and this was their latest experiment. The emphasis is on spectacle on a nearly cartoonish scale, the money shot being the "bevy of singing, dancing beauties atop an armada of airplanes!" But the studio had some not-so-secret weapons with more staying power. Note how the ad tries to sell the Carioca as a new dance craze, without really identifying it with the couple who introduce it in the picture. There was some flexibility about the billing, as you can tell by comparing the ad above with the ad on the left. Dolores Del Rio is consistently the top banana, but the order rotates underneath. Fred Astaire, whose first major film showcase this is, bounces between second billing and fifth, in one instance ahead of his dance partner, the already-established film star (and veteran of the Warners spectacles) Ginger Rogers, in another beneath her. In retrospect, the way RKO learned to use Rogers, compared to how Warners did, is as significant as how they used Astaire. Rogers's best-known moment in a Warners musical is her rendition of "We're In the Money" in Gold Diggers of 1933, but her singing is inevitably overshadowed by the Busby Berkeley spectacle surrounding her. By emphasizing her virtuosity as a dancer as well as a singer, RKO made her, with Astaire, the spectacle itself. By focusing on virtuosity rather than the spectacle of sheer numbers, the studio found the answer to Berkely and Warners after several false starts. RKO's earlier comic musicals are so cartoonish at points that they border on the inhuman; they do little to endear themselves to posterity, unless you're a connoisseur of Pre-Code strangeness like me. With Astaire and Rogers, RKO would usher in the classical period of the Hollywood musical.Here's a single-star vehicle opening at the Strand. In fact, they sell it like the star's biography.

It's a pretty funny picture in its grandly amoral way. I ought to give it a fresh look and write it up for the Pre-Code Parade sometime.

Finally, such a survey as ours would not be complete without the novelty of finding a film that no one remembers.

1933 was a pretty good year for Slim Summerville. He was part of a popular team with ZaSu Pitts and Horse Play may have been an attempt to launch a second franchise with Summerville and (god help us) Andy Devine. Whatever this is, it's clearly in competition with Duck Soup; you wouldn't advertise a movie as "a cockeyed nightmare of fun" otherwise. And admit it: if you heard about a cockeyed nightmare of fun happening somewhere, wouldn't you be interested? Strange to say, Slim himself doesn't look too interested in the ad. Maybe he knows something we don't, since for the time being Horse Play must remain a mystery to us. The past should always be a little mysterious, I suppose; it keeps us interested and leads to us learning things. I hope that people learned something or were at least entertained slightly by this series over the past year. I may pick another year and another city as a project for 2014, but I haven't decided yet. I'll make a resolution to make my mind up, and in the meantime I wish you all a Happy New Year -- or to be more modest, a Happy New Year's Day.

F

F

C

C

A

A

D

D

A

A

W

W I

I

N

N

T

T I

I