A randomly comprehensive survey of extraordinary movie experiences from the art house to the grindhouse, featuring the good, the bad, the ugly, but not the boring or the banal.

Showing posts with label 1970s. Show all posts

Showing posts with label 1970s. Show all posts

Thursday, September 19, 2019

DVR Diary: EMITAI (1971)

World War II wasn't the "good war" everywhere. Far from Europe, in Europe's colonies, what Hitler was up to hardly mattered. In some places the Allies, the good guys of the usual narrative were the oppressors. That's the context of Ousmane Sembene's war picture, which shows the war's impact on the Diola people in French-ruled Senegal. They and their crops are resources for France to draw upon at will. Emitai starts with colonial troops pressing villagers into military service. The young men must listen to a French officer praise them for volunteering and exhort them to revere and obey Marshal Petain, at that moment (Spring 1940) France's last hope against the Nazis. One year later, Petain leads a collaborationist regime, but France's alignment means little to the Diola, who are now required to give up their rice crops to the colonial power. The village elders debate the necessity for revolt and, perhaps more importantly, the will of the gods. Their chief has grown skeptical toward the pantheon -- if not toward their existence, then toward their effectiveness in this modern crisis. Ironically, it's he, mortally wounded in a futile uprising, who receives a vision of the gods. They chide him for his lack of faith, while he reproaches them for their apparent indifference to their worshipers' dire situation. After he dies, the film slows down as the village prepares for the chief's funeral, the remaining elders -- in hiding from the colonial troops -- ponder how to appease the gods and/or the French, while two French officers and their native troops hold the women and children hostage, with rice as the ransom. Sembene's deliberate, novelistic pacing -- he was a novelist before taking up the camera -- immerses the viewer in the life of the embattled village while steadily heating up indignation against the elders' preoccupation with the gods. They balk (rightly) at sacrificing rice to the French, but then one sacrifices a goat to the gods on impulse. The bawling animal has its throat cut and bleeds out before being dumped like so much garbage. Sembene respects Diola culture in the broadest sense but is clearly secular in his sympathies, or at least highly critical toward religion. The elders' folly sometimes nearly overshadows the oppression of the French, who switch sides in the world war, abandoning Petain for de Gaulle, with no change in their treatment of the Diola. But the film ends with a sharp reminder that, whatever their faults, the elders, like their fellow villagers, are essentially villagers of a regime that must have seemed little better to them than any tale of Nazi rule the French might have told them. Unsurprisingly, several years passed before either Senegalese or French people could see Emitai, but films like Sembene's are valuable, not necessarily as correctives to a particular narrative of World War II, but as examples of perspectives from which the moral drama of that conflict is not and never will be central, and the winners of it may never be the good guys.

Wednesday, July 31, 2019

DEVIL'S EXPRESS (Gang Wars, 1976)

First-time director Barry Rosen bet on a Seventies genre trifecta by making a blaxploitation martial-arts horror film, and while I wouldn't call it a good movie it is an often-fascinating document of the fantasy life springing from the grungy state of urban life at that time. In its Mummy-inspired prologue, ancient Chinese monks lower a mysterious casket, with an amulet attached, into a hole in the earth. To ensure that no one knows the location of the burial, the leader of the little group kills everyone else before putting himself to the sword. While he might well have waited until they'd all done something to cover the hole, no one actually discovers the mystery inside until centuries later.

In 1970s Harlem, martial-arts instructor Luke (Warhawk Tanzania) spars with his friend Cris (Larry Fleischman). It's a tense friendship since Luke is black and Cris is a white cop, but as Luke explains to his suspicious students, he owes Cris a favor. In any event, Luke and his student-buddy Rodan (Wilfredo Roldan) are soon off to Hong Kong for some elite training. Rodan's head really isn't into the discipline -- he's more of a thug at heart -- but Luke earns a diploma after a match with the master. After that, Luke is sent to an island to meditate, while Rodan is tasked with watching over him. Bored by it all, Rodan just happens to discover the pit that generations of random explorers and possible treasure hunters managed to miss. Lowering himself in with ease, he snatches the amulet and takes it home to America with him.

The Hong Kong-New York steamer has another passenger: a Chinese man who suddenly finds himself possessed by some unseen entity. By the time he reaches the U.S. he's a staggering, bug-eyed mess terrified by every bright light and sharp sound until he finds a sort of shelter in the subway system. Now whatever's inside him can come into its own, though the filmmakers don't quite have the money to do more than suggest a chest-bursting exit with a lot of bleeding.

Meanwhile, Rodan and his gang buddies escalate their feud with a Chinese gang after he gets ripped off in a cocaine deal. In a violent variation on West Side Story the Chinese and black/Hispanic gangs perform martial-arts rumbles in the slums of New York, where the producers enjoyed extensive municipal cooperation despite their film's unflattering snapshot of Seventies squalor. As the gang war escalates, Cris and the rest of the police begin investigating a subway serial killer. While his comedy-relief partner invokes urban legends of mutant animals, Cris suspects that the killings are gang-related, despite Luke's vehement pushback against that suggestion. Luke's attitude toward his friends is strangely ambivalent. He warns them constantly against using martial arts in anger, but it's unclear whether he even realizes that Rodan is a drug dealer or if he would care. He lives in a sort of ebony tower, content to make love to his girlfriend and improve his knowledge until the killings come to close to home.

As you might guess, the subway entity is drawn to Rodan for the amulet he wears -- but by the time it finally catches up with him, the Chinese gang has snatched it away. That's how their wise old mentor is finally able to explain the actual situation to Luke, once the Chinese convince him that they weren't the ones who slammed Rodan face-first into a transformer. Only Luke has the mental discipline to defeat the monster, which adds an arsenal of psychic attacks to its arsenal for the final showdown in the tunnels. It takes a variety of forms, including Rodan and later two fighters at once, before trying to convince Luke that trains are bearing down on him. For Rosen it's a brave effort at something trippy and supernatural, but when the monster finally shows its true form and goes for a death grapple the scene is too dark to appreciate either the monster get-up or the climactic action.

While Devil's Express ends on an underwhelming note, it's an admirable B-film in which everyone seems to be trying hard to make an impression. Warhawk Tanzania (who made only one more film) is no real actor but at least errs on the side of excess, and while the fighting isn't much by Chinese standards (and the gore effects are mostly laughable) Rosen and his co-writers manage to invest each encounter with some dramatic urgency. They also find time for gratuitously entertaining stuff like a fight between a male bully and a female bartender at Luke's favorite watering hole and a cameo by misanthropic performance artist Brother Theodore -- he may be remembered from the early years of David Letterman's late-night show -- as a priest slowly driven mad by the subway killings. There's a likable cacophany to the pre-climactic scene where Luke negotiates with the cops to let him go into the tunnels alone while the priest rants to the assembled crowd about dead gods, pestiferous rats and whatnot. Rosen's enthusiasm makes it regrettable that he directed only one more film, though he's gone on to a long career as a TV producer. For Devil's Express he threw a lot of stuff at the screen to see what would stick, and that's almost certain to leave at least something for some of us to like.

In 1970s Harlem, martial-arts instructor Luke (Warhawk Tanzania) spars with his friend Cris (Larry Fleischman). It's a tense friendship since Luke is black and Cris is a white cop, but as Luke explains to his suspicious students, he owes Cris a favor. In any event, Luke and his student-buddy Rodan (Wilfredo Roldan) are soon off to Hong Kong for some elite training. Rodan's head really isn't into the discipline -- he's more of a thug at heart -- but Luke earns a diploma after a match with the master. After that, Luke is sent to an island to meditate, while Rodan is tasked with watching over him. Bored by it all, Rodan just happens to discover the pit that generations of random explorers and possible treasure hunters managed to miss. Lowering himself in with ease, he snatches the amulet and takes it home to America with him.

The Hong Kong-New York steamer has another passenger: a Chinese man who suddenly finds himself possessed by some unseen entity. By the time he reaches the U.S. he's a staggering, bug-eyed mess terrified by every bright light and sharp sound until he finds a sort of shelter in the subway system. Now whatever's inside him can come into its own, though the filmmakers don't quite have the money to do more than suggest a chest-bursting exit with a lot of bleeding.

Meanwhile, Rodan and his gang buddies escalate their feud with a Chinese gang after he gets ripped off in a cocaine deal. In a violent variation on West Side Story the Chinese and black/Hispanic gangs perform martial-arts rumbles in the slums of New York, where the producers enjoyed extensive municipal cooperation despite their film's unflattering snapshot of Seventies squalor. As the gang war escalates, Cris and the rest of the police begin investigating a subway serial killer. While his comedy-relief partner invokes urban legends of mutant animals, Cris suspects that the killings are gang-related, despite Luke's vehement pushback against that suggestion. Luke's attitude toward his friends is strangely ambivalent. He warns them constantly against using martial arts in anger, but it's unclear whether he even realizes that Rodan is a drug dealer or if he would care. He lives in a sort of ebony tower, content to make love to his girlfriend and improve his knowledge until the killings come to close to home.

As you might guess, the subway entity is drawn to Rodan for the amulet he wears -- but by the time it finally catches up with him, the Chinese gang has snatched it away. That's how their wise old mentor is finally able to explain the actual situation to Luke, once the Chinese convince him that they weren't the ones who slammed Rodan face-first into a transformer. Only Luke has the mental discipline to defeat the monster, which adds an arsenal of psychic attacks to its arsenal for the final showdown in the tunnels. It takes a variety of forms, including Rodan and later two fighters at once, before trying to convince Luke that trains are bearing down on him. For Rosen it's a brave effort at something trippy and supernatural, but when the monster finally shows its true form and goes for a death grapple the scene is too dark to appreciate either the monster get-up or the climactic action.

While Devil's Express ends on an underwhelming note, it's an admirable B-film in which everyone seems to be trying hard to make an impression. Warhawk Tanzania (who made only one more film) is no real actor but at least errs on the side of excess, and while the fighting isn't much by Chinese standards (and the gore effects are mostly laughable) Rosen and his co-writers manage to invest each encounter with some dramatic urgency. They also find time for gratuitously entertaining stuff like a fight between a male bully and a female bartender at Luke's favorite watering hole and a cameo by misanthropic performance artist Brother Theodore -- he may be remembered from the early years of David Letterman's late-night show -- as a priest slowly driven mad by the subway killings. There's a likable cacophany to the pre-climactic scene where Luke negotiates with the cops to let him go into the tunnels alone while the priest rants to the assembled crowd about dead gods, pestiferous rats and whatnot. Rosen's enthusiasm makes it regrettable that he directed only one more film, though he's gone on to a long career as a TV producer. For Devil's Express he threw a lot of stuff at the screen to see what would stick, and that's almost certain to leave at least something for some of us to like.

Thursday, July 11, 2019

LEGACY OF SATAN (1972)

Inside every porno filmmaker, I suppose, is an aspiring mainstream director. The pay is better and you're not as bound by genre conventions, no matter what critics of Hollywood say. The ambition was there, however briefly, in Gerard Damiano, who enjoyed a moment of fame -- somewhere between notoriety and celebrity -- when his film Deep Throat became a surprise hit in 1972. He followed that up with another quasi-crossover hit, The Devil in Miss Jones, in 1973. If anyone was positioned to attempt a crossover into true mainstream filmmaking, it was Damiano. In fact, he had already taken his shot. Filmed in the year Deep Throat was released, Legacy of Satan played double bills with The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, but to my knowledge the Deep Throat connection went unmentioned. That's just as well, since it would only have created false expectations for a movie that seems closer to a PG rating -- at least in the version I saw -- than the R it received. It's a shame that Damiano didn't wait until after Deep Throat had hit before trying this, as he could almost certainly have gotten a bigger budget to work with. Instead, while displaying some pictorial ambition, Legacy looks cheap and slapdash, and while more money might have gotten the director better actors, the shabby screenplay is all on him.

The story plays out like an old eight-page horror comic in which wild things happen with little regard for why they happen. After a demonic ritual -- the villains worship an entity called Rakheesh rather than Satan -- plays out under the opening credits -- we sit in on a husband and wife, George and Maya, talking to their friend Arthur, who's quit his job to become a sort of spiritual seeker. Arthur proves to be a kind of talent scout for the cult leader, Dr.Muldavo, who enthuses over a photograph of Maya as if she were his reincarnated lost love. This visibly irks Muldavo's mistress/henchwoman Aurelia, but since she's a mute there's not much she can say about it.

Maya begins to have disturbing dreams and behaves disturbingly, too. One fine day, just before they're scheduled to visit Dr. Muldavo at Arthur's invitation, she deliberately slices her finger and makes George suck the blood. The Rakheesh worshippers are blood drinkers, you see, Aurelia being the current supplier for Muldavo. George isn't sure what to make of all this, while Maya is subject to mood swings that only add to her husband's confusion.

At Chez Muldavo, Maya and George are slipped a couple of Mickeys. For Maya it's like a hit of Reefer Madness-grade marijuana, setting her prancing about the room, while George basically passes out. He's quickly locked away so Muldavo can put the moves on Maya, but before any unholy marriage can be consummated, jealous Aurelia frees George and arms him with a magic, or at least a glowing sword. She gets stabbed for her trouble, but George avenges her by slashing Muldavo's face with the burning blade, sending the cult leader pitching over a balcony.

George and Maya run for it, but Maya -- how like a female -- asks for a rest. But aha! George was too late after all. Maya has turned, and asked for a time out only so the cultists could catch up and kill her husband. Now she tends to poor Muldavo, who survived the fall but has suffered a hideous, constantly worsening facial burn. Only fresh blood can save him, so Maya sets about exsanguinating some cult members -- but to no avail. To her despair, Muldavo succumbs, leaving her to plead with Rakheesh for some sign that they'll be together again. We get the sign at the very end, when Maya turns her head to reveal a scar like her late beloved's growing on her face. In the absence of any actual character development (or "arc") for Maya, Legacy gives us little more than a nearly random sequence of strange behaviors -- and nobody else has nearly as much development as Maya. Nor can any of the cast act, as far as I could tell here. Legacy fails as transgressive cinema. What I saw appears to have some gore cut out, unless I'm only noticing editor Damiano's ineptitude, and there's no nudity whatsoever. It ends up reminiscent in ways of Andy Milligan's work, with which Legacy was sometimes associated in double-bills, but without Milligan's splenetic attitude. There's no real personality at all here, and I wouldn't be surprised if students of Damiano assured us that some of his pornos are better cinema. Maybe things would have been different if he did this a little later, flush with success and possibly roaring with ambition, but maybe he'd already found his true medium, and horror movies simply weren't it.

The story plays out like an old eight-page horror comic in which wild things happen with little regard for why they happen. After a demonic ritual -- the villains worship an entity called Rakheesh rather than Satan -- plays out under the opening credits -- we sit in on a husband and wife, George and Maya, talking to their friend Arthur, who's quit his job to become a sort of spiritual seeker. Arthur proves to be a kind of talent scout for the cult leader, Dr.Muldavo, who enthuses over a photograph of Maya as if she were his reincarnated lost love. This visibly irks Muldavo's mistress/henchwoman Aurelia, but since she's a mute there's not much she can say about it.

Maya begins to have disturbing dreams and behaves disturbingly, too. One fine day, just before they're scheduled to visit Dr. Muldavo at Arthur's invitation, she deliberately slices her finger and makes George suck the blood. The Rakheesh worshippers are blood drinkers, you see, Aurelia being the current supplier for Muldavo. George isn't sure what to make of all this, while Maya is subject to mood swings that only add to her husband's confusion.

At Chez Muldavo, Maya and George are slipped a couple of Mickeys. For Maya it's like a hit of Reefer Madness-grade marijuana, setting her prancing about the room, while George basically passes out. He's quickly locked away so Muldavo can put the moves on Maya, but before any unholy marriage can be consummated, jealous Aurelia frees George and arms him with a magic, or at least a glowing sword. She gets stabbed for her trouble, but George avenges her by slashing Muldavo's face with the burning blade, sending the cult leader pitching over a balcony.

George and Maya run for it, but Maya -- how like a female -- asks for a rest. But aha! George was too late after all. Maya has turned, and asked for a time out only so the cultists could catch up and kill her husband. Now she tends to poor Muldavo, who survived the fall but has suffered a hideous, constantly worsening facial burn. Only fresh blood can save him, so Maya sets about exsanguinating some cult members -- but to no avail. To her despair, Muldavo succumbs, leaving her to plead with Rakheesh for some sign that they'll be together again. We get the sign at the very end, when Maya turns her head to reveal a scar like her late beloved's growing on her face. In the absence of any actual character development (or "arc") for Maya, Legacy gives us little more than a nearly random sequence of strange behaviors -- and nobody else has nearly as much development as Maya. Nor can any of the cast act, as far as I could tell here. Legacy fails as transgressive cinema. What I saw appears to have some gore cut out, unless I'm only noticing editor Damiano's ineptitude, and there's no nudity whatsoever. It ends up reminiscent in ways of Andy Milligan's work, with which Legacy was sometimes associated in double-bills, but without Milligan's splenetic attitude. There's no real personality at all here, and I wouldn't be surprised if students of Damiano assured us that some of his pornos are better cinema. Maybe things would have been different if he did this a little later, flush with success and possibly roaring with ambition, but maybe he'd already found his true medium, and horror movies simply weren't it.

Thursday, May 2, 2019

THE HOT BOX (1972)

The women's prison film was only the most common form of a captivity narrative that was strangely quite popular in Seventies cinema. These films are often girl-power stories in some way, yet the idea seems to be to give the girls something to really rebel against in place of mere male chauvinism -- or else it was to offer a sufficiently exaggerated metaphor for male domination to make audience's vicarious enjoyment of women's lethal revenge ultimately harmless. Whatever the deal was, Roger Corman proteges Jonathan Demme and Joe Viola joined forces in the Philippines to shoot this variation on the formula, with future Oscar-winner Demme as producer and co-writer. In this one, four American nurses working in the fictional Republic of San Rosario -- two blondes, one brunette and one black -- are taken captive by a revolutionary army while on an outing with some native male friends. The men are set adrift while the bikini-clad Americans are led into the jungle by an especially rude band of rebels. These men are little more than mercenaries, but the revolutionary leader, Flavio (Carmen Argenziano) is a more honorable man. He needs nurses to tend his troops, and the girls can either join or die.

Margaret Markov, Pam Grier's co-star in The Arena and Black Mama, White Mama, is probably the best known of the actresses. Her character gets the radicalization angle, beginning to sympathize with the People's Army as she recognizes the desperation of their plight, while the black character (Rickey Richardson) takes an ironically stereotyped view of the "filthy" San Rosarians. If she wanted to take part in a revolution, she tells someone, she could go back home to Chicago. The nurses notice a rift between Flavio and one of his trusted lieutenants, the knife master Ronaldo (Zaldy Zchornack), who seems more pragmatic than his sometimes-bullheaded leader, who basks in the publicity provided by radical war correspondent Garcia (Charles Dierkop). As Ronaldo grows more dissatisfied, the Americans see him as their way out.

Sure enough, Ronaldo leads them to safety, or so he and they think. Instead, he's led them from the frying pan into the fire. It turns out that Ronaldo had been informing for the government because they were holding his brothers hostage. It also turns out that Garcia the journalist is actually a military officer planning to ambush and wipe out the clueless Flavio's forces. We see at last that the government, represented by Garcia, is far worse than the revolutionaries. The dishonorable officer has had Ronaldo's brothers put to death and promises the same fate for Ronaldo himself. He turns three of the nurses over to his men for a title-justifying stint in a cage bombarded by a steam hose, while reserving the fourth for his rapey self. Realizing the profound error of their ways, the nurses and Ronaldo manage to escape and warn Flavio of Garcia's plans, giving him a chance to ambush the ambushers in a climactic battle in which the American women take a fighting part.

The Hot Box is blatant, unapologetic exploitation. The nurses are often topless, sometimes against their will, and their long-legged good looks are the obvious main attraction. Inevitably they turn into amazons, and for the most part they look the part. Acting honors clearly belong to Dierkop, who goes from inconspicuous hanger-on all they way over the top to scenery-chewing big bad. It's not exactly a good performance, but it's great for this kind of film because he really makes you want his character dead. Viola's direction goes into another gear in sync with Dierkop's performance, enhancing an already pulpy story with wipes and other cartoony transitions as the pace picks up. The screenplay has some nice touches, like a surprise reappearance by the sleazy mercenaries and a two-part gag in which the nurses and Ronaldo steal a man's motorboat, only to return it neatly to him on their way back -- before stealing his truck. The film moves at a good clip and keeps busy, which is either the least or the most we can ask of such a project. By now films like this are objects of nostalgia as much as they are entertainments. This one in particular is the sort of film that doesn't get made anymore; you see neither its crude presentation of women nor their transformation into avatars of revolution. It can probably be only a guilty pleasure now, but if you're in the proper frame of mind it can still be unpretentious, energetic fun.

Margaret Markov, Pam Grier's co-star in The Arena and Black Mama, White Mama, is probably the best known of the actresses. Her character gets the radicalization angle, beginning to sympathize with the People's Army as she recognizes the desperation of their plight, while the black character (Rickey Richardson) takes an ironically stereotyped view of the "filthy" San Rosarians. If she wanted to take part in a revolution, she tells someone, she could go back home to Chicago. The nurses notice a rift between Flavio and one of his trusted lieutenants, the knife master Ronaldo (Zaldy Zchornack), who seems more pragmatic than his sometimes-bullheaded leader, who basks in the publicity provided by radical war correspondent Garcia (Charles Dierkop). As Ronaldo grows more dissatisfied, the Americans see him as their way out.

Sure enough, Ronaldo leads them to safety, or so he and they think. Instead, he's led them from the frying pan into the fire. It turns out that Ronaldo had been informing for the government because they were holding his brothers hostage. It also turns out that Garcia the journalist is actually a military officer planning to ambush and wipe out the clueless Flavio's forces. We see at last that the government, represented by Garcia, is far worse than the revolutionaries. The dishonorable officer has had Ronaldo's brothers put to death and promises the same fate for Ronaldo himself. He turns three of the nurses over to his men for a title-justifying stint in a cage bombarded by a steam hose, while reserving the fourth for his rapey self. Realizing the profound error of their ways, the nurses and Ronaldo manage to escape and warn Flavio of Garcia's plans, giving him a chance to ambush the ambushers in a climactic battle in which the American women take a fighting part.

The Hot Box is blatant, unapologetic exploitation. The nurses are often topless, sometimes against their will, and their long-legged good looks are the obvious main attraction. Inevitably they turn into amazons, and for the most part they look the part. Acting honors clearly belong to Dierkop, who goes from inconspicuous hanger-on all they way over the top to scenery-chewing big bad. It's not exactly a good performance, but it's great for this kind of film because he really makes you want his character dead. Viola's direction goes into another gear in sync with Dierkop's performance, enhancing an already pulpy story with wipes and other cartoony transitions as the pace picks up. The screenplay has some nice touches, like a surprise reappearance by the sleazy mercenaries and a two-part gag in which the nurses and Ronaldo steal a man's motorboat, only to return it neatly to him on their way back -- before stealing his truck. The film moves at a good clip and keeps busy, which is either the least or the most we can ask of such a project. By now films like this are objects of nostalgia as much as they are entertainments. This one in particular is the sort of film that doesn't get made anymore; you see neither its crude presentation of women nor their transformation into avatars of revolution. It can probably be only a guilty pleasure now, but if you're in the proper frame of mind it can still be unpretentious, energetic fun.

Thursday, April 25, 2019

On the Big Screen: BLIND WOMAN'S CURSE (1970)

Teruo Ishii might be called the Tod Browning of Japanese cinema. He shared with his American precursor an interest in crime and an instinct for the grotesque. These converge in Blind Woman's Curse, an early starring role for 70s death-goddess Meiko Kaji that I got to see at the Proctor's GE Theater thanks to the It Came From Schenectady cult film society. If some of the film's virtually supernatural elements seem incongruous in a yakuza film, bear in mind that its setting is implicitly a fantasy film, one in which a yakuza boss can be described as pure in heart. That boss is our star, playing Akemi Tachibana, who inherited the mantle and the unquestioned loyalty of her henchmen from her father. She's a fighting boss, as demonstrated in a formal showdown with another gang during the opening credits, and almost unconsciously charismatic, as demonstrated when, serving time for her role in the fight, she converts some skeptical fellow convicts in a women's prison into future soldiers. Her clan controls a public market but is regularly challenged by her clownish rivals, the Aozora clan. These challenges aren't to be taken too seriously, since the primary attribute of the Aozora boss (Ryohei Uchida) is the long-unwashed loincloth that adorns his prominently displayed buttocks. But when a retaliatory raid on his gang goes terribly wrong, Akemi comes under increasing pressure to escalate the feud.

As we quickly learn, events are being manipulated by a third gang, led by the ambitious Dobashi (Toru Abe) and abetted by a traitor in Akemi's midst. The provocations grow more extreme as Akemi's followers are stripped of the dragon tattoos that adorn their backs and a dubious feline is seen licking at the flayed remnants. There are, in fact, still more players in the game. One is a soft-spoken swordswoman (Hoki Tokuda -- at the time Mrs. Henry Miller!) who happens to be blind. She happens to have been blinded by Akemi in that opening-credits fight, during which her brother was killed. She actually looks really good for someone who apparently had her eyes slashed, and of course, this being Japan, her handicap confers a compensatory advantage in fighting skill. A cat licking her wounds immediately after the injury probably helped as well. Anyway, you get the idea; she's out for vengeance against Akemi. Meiko Kaji is the object of vengeance for once, that is, but this was still early in her career before she was set in her ways.

What the story is with the blind woman's sidekick, who can say? Ushimatsu is hunchbacked performance artist, played by Tatsumi Hijikata, credited as a creator of the modern dance form of butoh. We're treated to one of his strange performances, enhanced (if that's the word) by Ishii's (and Osamu Inoue's) frantic editing. We're also treated (if that's the word) to his hobby, which is maintaining a carny house of horrors featuring fake (???) severed heads, limbs, etc. Ushimatsu appears to go above and beyond whatever mandate the blind swordswoman or Dobashi gave him, and his exploits are pretty much the essence of this picture. At one point, after the more conventional thugs have bumped off Akemi's wise old uncle, the rare yakuza who has gone straight, the hunchback shows up to lick and fondle the corpse. Later, the apparently living corpse shows up to spook some people, but when the head promptly rolls off we see that Ushimatsu is just having fun with his new meat puppet. As far as movie hunchbacks go, this guy makes Paul Naschy in Hunchback of the Morgue look like Quasi from the Disney cartoon.

Things can't go on like this forever -- can they? -- so finally Akemi's had all she can stand, til she can't stands no more. Once the traitor in her midst is exposed, she leads the climactic assault on Dobashi's headquarters, except that it's only a warmup for the inevitable showdown between our jingi-licious heroine and the blind swordswoman. Again, in Japan you always bet on the handicapped person in these encounters, even if it's Meiko Kaji on the other side. Only this time, you wouldn't collect, because nobody wins. After the damned cat tries to interfere and gets gutted for its trouble, it looks like Akemi is down for the count. She's waiting for the coup de grace, but it never comes, for the blind swordswoman can tell -- she usually can smell such things -- that our yakuza boss lady is genuinely repentant about killing her brother and the other stuff. She accepts this as an apology, takes her dying cat and goes home. But let's face it: anything after what we've already seen in this picture is going to be an anticlimax, and maybe that's for the best. Otherwise people are bound to leave the theater in a disoriented state dangerous to themselves and others. As it is, the downbeat-yet-upbeat finish gives viewers time to reflect on the fact that, for all its excesses and confusions Blind Woman's Curse is goofy fun, as long as you're in the right -- or fright -- frame of mind.

As we quickly learn, events are being manipulated by a third gang, led by the ambitious Dobashi (Toru Abe) and abetted by a traitor in Akemi's midst. The provocations grow more extreme as Akemi's followers are stripped of the dragon tattoos that adorn their backs and a dubious feline is seen licking at the flayed remnants. There are, in fact, still more players in the game. One is a soft-spoken swordswoman (Hoki Tokuda -- at the time Mrs. Henry Miller!) who happens to be blind. She happens to have been blinded by Akemi in that opening-credits fight, during which her brother was killed. She actually looks really good for someone who apparently had her eyes slashed, and of course, this being Japan, her handicap confers a compensatory advantage in fighting skill. A cat licking her wounds immediately after the injury probably helped as well. Anyway, you get the idea; she's out for vengeance against Akemi. Meiko Kaji is the object of vengeance for once, that is, but this was still early in her career before she was set in her ways.

What the story is with the blind woman's sidekick, who can say? Ushimatsu is hunchbacked performance artist, played by Tatsumi Hijikata, credited as a creator of the modern dance form of butoh. We're treated to one of his strange performances, enhanced (if that's the word) by Ishii's (and Osamu Inoue's) frantic editing. We're also treated (if that's the word) to his hobby, which is maintaining a carny house of horrors featuring fake (???) severed heads, limbs, etc. Ushimatsu appears to go above and beyond whatever mandate the blind swordswoman or Dobashi gave him, and his exploits are pretty much the essence of this picture. At one point, after the more conventional thugs have bumped off Akemi's wise old uncle, the rare yakuza who has gone straight, the hunchback shows up to lick and fondle the corpse. Later, the apparently living corpse shows up to spook some people, but when the head promptly rolls off we see that Ushimatsu is just having fun with his new meat puppet. As far as movie hunchbacks go, this guy makes Paul Naschy in Hunchback of the Morgue look like Quasi from the Disney cartoon.

Things can't go on like this forever -- can they? -- so finally Akemi's had all she can stand, til she can't stands no more. Once the traitor in her midst is exposed, she leads the climactic assault on Dobashi's headquarters, except that it's only a warmup for the inevitable showdown between our jingi-licious heroine and the blind swordswoman. Again, in Japan you always bet on the handicapped person in these encounters, even if it's Meiko Kaji on the other side. Only this time, you wouldn't collect, because nobody wins. After the damned cat tries to interfere and gets gutted for its trouble, it looks like Akemi is down for the count. She's waiting for the coup de grace, but it never comes, for the blind swordswoman can tell -- she usually can smell such things -- that our yakuza boss lady is genuinely repentant about killing her brother and the other stuff. She accepts this as an apology, takes her dying cat and goes home. But let's face it: anything after what we've already seen in this picture is going to be an anticlimax, and maybe that's for the best. Otherwise people are bound to leave the theater in a disoriented state dangerous to themselves and others. As it is, the downbeat-yet-upbeat finish gives viewers time to reflect on the fact that, for all its excesses and confusions Blind Woman's Curse is goofy fun, as long as you're in the right -- or fright -- frame of mind.

Sunday, April 7, 2019

DVR Diary: THE BURGLARS (Le Casse, 1971)

There's no point to judging Henri Verneuil's free adaptation of David Goodis' noir novel The Burglar by its fidelity to the source material. Goodis himself wrote a previous film adaptation which by definition must stand as definitive, so we may as well accept Le Casse for what it is: a vehicle for Jean-Paul Belmondo designed for the international-cast market. Goodis provides the bare bones of the story in which a slick safecracking gang goes to pieces while waiting to sell their plunder, but from there it's all Verneuil and co-writer Vahe Katcha. The action has been moved to Greece, where a crafty, somewhat corrupt police detective (Omar Sharif) picks the gang apart. The Belmondo character obviously proves the toughest nut to crack, so a local entertainer (Dyan Cannon) is called on to seduce and keep tabs on him. All of this is a framework on which to hang the action set pieces that audiences by now expected from Belmondo, who arguably qualifies as the missing link between Buster Keaton and Tom Cruise through his commitment to crazy stunt work. Keaton himself no doubt would have been proud of a then-unfakeable moment -- possibly inspired by Buster's own Seven Chances -- when Belmondo is dropped from a close-up position in the back of a truck down a steep gravel pit, with plenty of rocks following him down. Elsewhere, he clings from the outside to the window of a moving bus to avoid pursuers, only to transfer to another bus in the middle of a busy street. Beyond Belmondo's antics there's plenty here to suggest that Verneuil was a student of silent film. The picture opens with a fascinating, almost wordless sequence that shows how sophisticated a safecracker Belmondo is. The man basically carries a portable computer with him that allows him to program product specs and grind out a master key to order. If a film set around 1970 can qualify as steampunk, this scene should make La Casse eligible for that label. At the other end of the movie, the final fate of Sharif's character hearkens all the way back to D. W. Griffith's A Corner in Wheat or maybe Carl-Theodor Dreyer's Vampyr. Of course, a caper or crime film from this period wouldn't be complete without a proper car chase, and this one definitely delivers, even if it comes too early to be climactic. So much goes on in this picture that the car chase could almost be forgotten in the mix. Euro-stalwarts Robert Hossein and Renato Salvatori are along for the ride but this is clearly Belmondo's show, which means he doesn't have to do much with his character but live up to his pop persona. Some of his exploits wouldn't fly today -- it's meant as a gag when he slaps Cannon so hard and repeatedly that he sets off a room's light controls -- but for a good part of the world in his heyday he was the fantasy ideal of a man's man, and nothing about La Casse would change that. It's pretty much the opposite of the sort of noir one might expect from a Goodis adaptation, but on its own terms it's an often very entertaining action picture sure to appeal to Euro-Seventies fans.

Saturday, March 16, 2019

DVR Diary: ANOTHER SON OF SAM (1977)

Aspiring North Carolina auteur Dave A. Adams reportedly wrote and directed his first film, originally called "Hostages," in 1975. It took two years for him to find an exploitation angle, but in late 1977 Adams anointed his film's killer Another Son of Sam. All it took was to preface the picture with a lineage of killers starting with Jack the Ripper and concluding with the then still active Hillside Strangler. It might not inspire confidence to see Adams attribute fourteen victims to the Ripper, but a friend tells me that many Ripperologists at least tentatively credit Jack with more than the canonical five killings. Whether Adams knew this is unclear, bur you'd be right anyway not to have confidence in him. For what it's worth, his original concept arguably owes more to another killer in Adams' list, Richard Speck, since Adams' killer spends much of his time in a girls' dormitory. This killer, Harvey, escapes from the hospital after a round of electroshock therapy and heavy sedation, despite being put in a straitjacket. He strangles one guard with a telephone cord, then impales another with a coat rack. Through all of this, we haven't seen the man's face, but we get repeated close-ups of his actually quite inexpressive eyes. No madness seethes there, nor does depravity glisten in them. Nevertheless, these repeated shots of his eyes are this film's equivalent of Bela Lugosi spreading his cape in Plan 9 From Outer Space.

Despite his murderous ways, Harvey is satisfied merely to knock his doctor unconscious. We're told that she's in a coma, but suffering more from shock than anything else. That's enough to enrage the doctor's husband, a plainclothes detective, though rage seems to be beyond the actor's emotional range. He's given a backstory that consumes the first reel of the picture and consists of speedboating and the patronage of a nightclub where Johnny Charro, a stereotypical hairy-chested real-life local lounge singer, performs. Charro's awful ballad, "I Never Said Goodbye," is a local hit, receiving radio airplay in at least one scene, and counts as the Love Theme from Another Son of Sam. As for the police detective, the most that can be said for our hero is that he's probably the most competent member of the Belmont police force. Once you see the picture, however, you'll realize that I'm not giving him much credit.

After he evades some cops in an urban park, Harvey follows two college students to their dorm. The girls' chatter introduces the major subplot of the picture, which is that one of them has stolen some money to finance an abortion. That this is implicitly obvious without abortion being mentioned is the one bit of cleverness in Adams' script. Harvey wanders through the building and for all I know is under the bed where the two girls have another chat, in order to justify more cut-ins of those evil eyes. We get a fake scare when one of the girls opens a closet door to fetch her pet mouse's cage, but instead of Harvey a large plush dog falls on her. Harvey will get his chance later.

The theft-abortion subplot provides an excuse for cops to be in the dorm when Harvey takes his first victim. A desultory siege ensues in which Harvey displays ninja skills relative to his inept police pursuers. At last a SWAT team is called in as Harvey menaces two of the girls we've already seen. He takes his time menacing them while the SWAT officer gingerly rappels into position, with orders to simply nose his rifle through an open window, part the curtain, and fire. One of the girls impatiently charges Harvey with one of those fraternity/sorority paddles, and at first it's unclear whether the madman has killed or merely kayoed her when she hits the mattress with blood trickling from her mouth. Meanwhile, the other girl makes her way to the window and tentatively parts the curtain. BANG! Score one for the cops. Then, another cop charges into the room, and for all his specialized training is immediately mowed down by Harvey. By this time the unconscious girl has come to, and she takes the carnage playing out around her with remarkable, almost inhuman calm.

Finally, Harvey's mother is brought to the dorm to talk him into surrendering. She tells a sob story, blaming herself for his going bad, and promises him on the cops' behalf that he won't be harmed if he turns himself in. Harvey, represented by the camera, steps into the hallway and stands in front of her, apparently staring at her handbag. The cops immediately open fire and it's as if the old lady has disappeared as Harvey, his face finally shown in mortal agony, is riddled with bullets. By way of an epilogue, the final girl from the dorm room gets the bad news from a doctor that her friend never regained consciousness, and she takes it with a great pout. We're left with no real insight into the homicidal mind, few quotably bad lines (though our hero's response to a false report of Harvey's capture, "There's a college girl here who would disagree with you -- if she could talk," is probably the 'best.') and nagging questions about the director's habit of freeze-framing the action while the dialogue continues. You might even ask whether this film every played in theaters, but as this was the Seventies, I'm sure that some drive-in or grindhouse did take it. Another Son of Sam isn't one of the laughably crazy bad films that provide genuine entertainment on some level, but if you'll settle for laughably inept it might still entertain you a little.

Despite his murderous ways, Harvey is satisfied merely to knock his doctor unconscious. We're told that she's in a coma, but suffering more from shock than anything else. That's enough to enrage the doctor's husband, a plainclothes detective, though rage seems to be beyond the actor's emotional range. He's given a backstory that consumes the first reel of the picture and consists of speedboating and the patronage of a nightclub where Johnny Charro, a stereotypical hairy-chested real-life local lounge singer, performs. Charro's awful ballad, "I Never Said Goodbye," is a local hit, receiving radio airplay in at least one scene, and counts as the Love Theme from Another Son of Sam. As for the police detective, the most that can be said for our hero is that he's probably the most competent member of the Belmont police force. Once you see the picture, however, you'll realize that I'm not giving him much credit.

After he evades some cops in an urban park, Harvey follows two college students to their dorm. The girls' chatter introduces the major subplot of the picture, which is that one of them has stolen some money to finance an abortion. That this is implicitly obvious without abortion being mentioned is the one bit of cleverness in Adams' script. Harvey wanders through the building and for all I know is under the bed where the two girls have another chat, in order to justify more cut-ins of those evil eyes. We get a fake scare when one of the girls opens a closet door to fetch her pet mouse's cage, but instead of Harvey a large plush dog falls on her. Harvey will get his chance later.

The theft-abortion subplot provides an excuse for cops to be in the dorm when Harvey takes his first victim. A desultory siege ensues in which Harvey displays ninja skills relative to his inept police pursuers. At last a SWAT team is called in as Harvey menaces two of the girls we've already seen. He takes his time menacing them while the SWAT officer gingerly rappels into position, with orders to simply nose his rifle through an open window, part the curtain, and fire. One of the girls impatiently charges Harvey with one of those fraternity/sorority paddles, and at first it's unclear whether the madman has killed or merely kayoed her when she hits the mattress with blood trickling from her mouth. Meanwhile, the other girl makes her way to the window and tentatively parts the curtain. BANG! Score one for the cops. Then, another cop charges into the room, and for all his specialized training is immediately mowed down by Harvey. By this time the unconscious girl has come to, and she takes the carnage playing out around her with remarkable, almost inhuman calm.

Finally, Harvey's mother is brought to the dorm to talk him into surrendering. She tells a sob story, blaming herself for his going bad, and promises him on the cops' behalf that he won't be harmed if he turns himself in. Harvey, represented by the camera, steps into the hallway and stands in front of her, apparently staring at her handbag. The cops immediately open fire and it's as if the old lady has disappeared as Harvey, his face finally shown in mortal agony, is riddled with bullets. By way of an epilogue, the final girl from the dorm room gets the bad news from a doctor that her friend never regained consciousness, and she takes it with a great pout. We're left with no real insight into the homicidal mind, few quotably bad lines (though our hero's response to a false report of Harvey's capture, "There's a college girl here who would disagree with you -- if she could talk," is probably the 'best.') and nagging questions about the director's habit of freeze-framing the action while the dialogue continues. You might even ask whether this film every played in theaters, but as this was the Seventies, I'm sure that some drive-in or grindhouse did take it. Another Son of Sam isn't one of the laughably crazy bad films that provide genuine entertainment on some level, but if you'll settle for laughably inept it might still entertain you a little.

Sunday, February 24, 2019

THE BAD BUNCH (1973)

Greydon Clark made his directorial debut and starred in this low-budget quasi-blaxploitation picture. It's not quite the real thing because Clark, a white man, is the point-of-view character throughout. It opens in Vietnam, represented by helicopter sound effects and some scrubby tall brush, as Jim (Clark) talks race relations with his black comrade-in-arms. This well-meaning person is about to reveal an idea he had for healing racial divisions when Charlie opens fire on the men, killing Jim's buddy. Stateside, Jim takes it upon himself to deliver a letter his buddy had written to his father, Tom Washington (Fred Scott). Arriving in Watts, Jim is immediately an object of suspicion and derision. Outside the old man's home, he has a tense encounter with a gang led by his buddy's brother, Tom Washington Jr. (Tom Johnigarn), or as he prefers, Makimba. As far as Makimba's concerned, it's Jim fault that his brother is dead, because Vietnam is a white man's war. The gang tracks Jim to a carnival and chases him down afterward. Before things get ugly, the cops show up. Then things get ugly, for the two middle-aged plainclothes white detectives (Aldo Ray and Jock Mahoney) are bigots looking for any excuse to take down black kids. Jim manages to defuse the situation but only earns the cops' contempt without winning any trust from Makimba.

Makimba might be the hero of a true blaxploitation picture, but here he's only a self-righteous asshole, kept from being an absolute villain only by the irredeemable racism of the cops and the audience's inferred understanding of the reality of places like Watts. He remains obsessed with getting some sort of revenge on the unoffending Jim. Meanwhile, Clark pads the film with an uninteresting love triangle involving Jim, his fiancee and a head-shop cashier he cheats on her with. You can't escape the impression that while he's supposed to be our hero, Jim's a bit of a sleaze who socializes at strip clubs, gets drunk and fears commitment. At the same time, Makimba is impotently resentful of the fact that his girlfriend has to turn tricks to pay the rent. Perhaps there's a faint echo here of the classic race-noir Odds Against Tomorrow, in which a white and black criminal who hate and ultimately destroy each other are shown to be pathetically miserable in their personal lives.

Somehow the plot contrives to get Makimba and his friends invited to a pool party thrown by Jim's friends in a Jewish neighborhood (Jim himself is Eastern Orthodox). It's an interesting scene that shows several of the gang loosening up and having fun with many of the whites while Jim remains gloweringly aloof. It's also an excuse for ample full-frontal female nudity, though as far as I noticed none of the men strips so completely before diving into the pool. An angry neighbor, offended at the site of "negroids" frolicking with whites, calls the cops on the party, forcing Makimba and friends to flee, almost missing the tardy Jim.

Makimba has only grown more paranoid about Jim because he's misinterpreted the white man's encounter with the cops at Tom Washington's funeral. Makimba's father had a fatal heart attack while scuffling with his son over the ammo for a rifle Makimba wants to shoot with. Jim wants to pay his respects and gets into an argument with the same racist cops from earlier in the picture. Seeing this from a distance, Makimba gets the idea that Jim has "fingered" him in some way. Thwarted at the pool party, Makimba desperately seeks another way to get at Jim, finally snatching the head-shop cashier and torturing her, despite the objections of his increasingly divided gang, to learn where Jim is. One of the gang is so repulsed by Makimba's mania that he actually rats his friend out to the racist cops, who race to the rescue only to get killed by the gang with knives, shovels, etc.

Now there's nothing left for Makimba to do but kill Jim, who has finally decided to go through with his marriage. Clark, who co-wrote the film, may have thought it a clever touch that Jim's overcoming his fear of commitment would prove his undoing, but since he does little, as actor or auteur, to make Jim an interesting personality, I doubt many in the audience cared much whether Jim got married or not. Unfortunately, I doubt many cared whether Jim got killed or not. For what it's worth, The Bad Bunch (also known as Tom or N----r Lover, after its title song) is a creation of its time, and so with characteristic pessimism it ends with Makimba killing Jim and a final split screen equating this murder with the death of Makimba's brother in war. While the film as a whole has a certain grungy authenticity that I appreciate in Seventies movies, its utterly one-dimensional treatment of Makimba undermines any point it meant to make about race relations. As an exploitation picture and a document of its time, however, it still has its moments of interest.

Makimba might be the hero of a true blaxploitation picture, but here he's only a self-righteous asshole, kept from being an absolute villain only by the irredeemable racism of the cops and the audience's inferred understanding of the reality of places like Watts. He remains obsessed with getting some sort of revenge on the unoffending Jim. Meanwhile, Clark pads the film with an uninteresting love triangle involving Jim, his fiancee and a head-shop cashier he cheats on her with. You can't escape the impression that while he's supposed to be our hero, Jim's a bit of a sleaze who socializes at strip clubs, gets drunk and fears commitment. At the same time, Makimba is impotently resentful of the fact that his girlfriend has to turn tricks to pay the rent. Perhaps there's a faint echo here of the classic race-noir Odds Against Tomorrow, in which a white and black criminal who hate and ultimately destroy each other are shown to be pathetically miserable in their personal lives.

Somehow the plot contrives to get Makimba and his friends invited to a pool party thrown by Jim's friends in a Jewish neighborhood (Jim himself is Eastern Orthodox). It's an interesting scene that shows several of the gang loosening up and having fun with many of the whites while Jim remains gloweringly aloof. It's also an excuse for ample full-frontal female nudity, though as far as I noticed none of the men strips so completely before diving into the pool. An angry neighbor, offended at the site of "negroids" frolicking with whites, calls the cops on the party, forcing Makimba and friends to flee, almost missing the tardy Jim.

Makimba has only grown more paranoid about Jim because he's misinterpreted the white man's encounter with the cops at Tom Washington's funeral. Makimba's father had a fatal heart attack while scuffling with his son over the ammo for a rifle Makimba wants to shoot with. Jim wants to pay his respects and gets into an argument with the same racist cops from earlier in the picture. Seeing this from a distance, Makimba gets the idea that Jim has "fingered" him in some way. Thwarted at the pool party, Makimba desperately seeks another way to get at Jim, finally snatching the head-shop cashier and torturing her, despite the objections of his increasingly divided gang, to learn where Jim is. One of the gang is so repulsed by Makimba's mania that he actually rats his friend out to the racist cops, who race to the rescue only to get killed by the gang with knives, shovels, etc.

Now there's nothing left for Makimba to do but kill Jim, who has finally decided to go through with his marriage. Clark, who co-wrote the film, may have thought it a clever touch that Jim's overcoming his fear of commitment would prove his undoing, but since he does little, as actor or auteur, to make Jim an interesting personality, I doubt many in the audience cared much whether Jim got married or not. Unfortunately, I doubt many cared whether Jim got killed or not. For what it's worth, The Bad Bunch (also known as Tom or N----r Lover, after its title song) is a creation of its time, and so with characteristic pessimism it ends with Makimba killing Jim and a final split screen equating this murder with the death of Makimba's brother in war. While the film as a whole has a certain grungy authenticity that I appreciate in Seventies movies, its utterly one-dimensional treatment of Makimba undermines any point it meant to make about race relations. As an exploitation picture and a document of its time, however, it still has its moments of interest.

Thursday, February 21, 2019

BLACK KILLER (1971)

As far as I can tell, "Black Killer" is the original title of this Italian western, even in its country of origin. That probably explains why the title creates a false impression. Based on what actor-turned-director Carlo "Lucky Moore" Croccolo shows us, the title probably should have been "Killer in Black." As the presumptive title character, Klaus Kinski is a man in black befitting his dignity as an attorney-at-law. He rides into Tombstone (pre or post-Earp?) with heavy law books dangling from his saddle. The books are his most precious possessions, and he gets antsy when anyone else tries to handle them. We see enough of one volume which flips open, apparently hollowed out, to raise our suspicions about James Webb's true line of work.

In fact, Webb has one of the dumbest gunfighter gimmicks in spaghetti westerns. The books, or some of them at least, are hollowed out and carry guns inside. That's one way to conceal your firearms, I suppose, but Webb takes the gimmick too far. Although there seems to be no advantage at all to it, the lawyer keeps his weapons between their covers at all times, even when he's using them. He's so good a gunman, I guess, that he doesn't have to worry about aiming -- and for that matter, I'm not quite sure how he fires the things unless each volume has a hidden lever somewhere. At least Croccolo doesn't force us to worry about these practical matters until late in the picture. Until then, Webb is mostly a seemingly detached observer of the tribulations of the Collins brothers at the hands of the O'Hara gang that dominates the territory by stealing land from homesteaders. Peter Collins (Jerry Ross) keeps a modest but happy home with his Indian wife Sarah (Marina Malfatti), while brother Burt (Fred Robsham) has been made sheriff, at Webb's prompting, after killing several outlaws shortly after reaching town. In revenge, the O'Hara's attack Peter's home, killing him, injuring Burt and raping Sarah. The murdered man's widow and brother become avengers, and say what else you will about this picture, it's a rare Italian western that gives us a fighting heroine, and a Native American at that. Sarah fights with bow and arrow (hitting her targets from sometimes impossible-seeming angles) and with guns, and even gets the drop on Webb when he acts suspiciously. She also provides some of the picture's gratuitous nudity, stripping to the buff so Burt can remove a bullet from her thigh. Most of the nudity is contributed by Consuelo the saloon girl (Tiziana Dini), who is as much an object of cinematic exploitation as Sarah is an exceptional heroine.

Alas, Sarah is made to sit out the final showdown pitting Webb and Burt against the remaining O'Haras, perhaps because "Lucky" realized that the Kinski character actually should accomplish something with his gimmicked lawbooks. I suppose you can read some kind of commentary into the gimmick on the inescapable violence at the heart of the rule of law, but I doubt anyone involved in this picture thought too much about it, and in any event Webb is not entirely a lawful character. He undoes the injustice of the land thefts, but keeps the gang's ill-gotten gains for himself, until Sheriff Burt demands a cut and gets it. At first this looked like one of those pictures Kinski would sleepwalk through, but Croccolo does a decent job exploiting the man's irrepressible presence as he glides desultorily through the proceedings. Webb isn't enough of a character to imagine a series of films about, and his gimmick really is dumb as a rock, but Kinski makes him fun to watch this one time without really doing much -- only just enough.

In fact, Webb has one of the dumbest gunfighter gimmicks in spaghetti westerns. The books, or some of them at least, are hollowed out and carry guns inside. That's one way to conceal your firearms, I suppose, but Webb takes the gimmick too far. Although there seems to be no advantage at all to it, the lawyer keeps his weapons between their covers at all times, even when he's using them. He's so good a gunman, I guess, that he doesn't have to worry about aiming -- and for that matter, I'm not quite sure how he fires the things unless each volume has a hidden lever somewhere. At least Croccolo doesn't force us to worry about these practical matters until late in the picture. Until then, Webb is mostly a seemingly detached observer of the tribulations of the Collins brothers at the hands of the O'Hara gang that dominates the territory by stealing land from homesteaders. Peter Collins (Jerry Ross) keeps a modest but happy home with his Indian wife Sarah (Marina Malfatti), while brother Burt (Fred Robsham) has been made sheriff, at Webb's prompting, after killing several outlaws shortly after reaching town. In revenge, the O'Hara's attack Peter's home, killing him, injuring Burt and raping Sarah. The murdered man's widow and brother become avengers, and say what else you will about this picture, it's a rare Italian western that gives us a fighting heroine, and a Native American at that. Sarah fights with bow and arrow (hitting her targets from sometimes impossible-seeming angles) and with guns, and even gets the drop on Webb when he acts suspiciously. She also provides some of the picture's gratuitous nudity, stripping to the buff so Burt can remove a bullet from her thigh. Most of the nudity is contributed by Consuelo the saloon girl (Tiziana Dini), who is as much an object of cinematic exploitation as Sarah is an exceptional heroine.

Alas, Sarah is made to sit out the final showdown pitting Webb and Burt against the remaining O'Haras, perhaps because "Lucky" realized that the Kinski character actually should accomplish something with his gimmicked lawbooks. I suppose you can read some kind of commentary into the gimmick on the inescapable violence at the heart of the rule of law, but I doubt anyone involved in this picture thought too much about it, and in any event Webb is not entirely a lawful character. He undoes the injustice of the land thefts, but keeps the gang's ill-gotten gains for himself, until Sheriff Burt demands a cut and gets it. At first this looked like one of those pictures Kinski would sleepwalk through, but Croccolo does a decent job exploiting the man's irrepressible presence as he glides desultorily through the proceedings. Webb isn't enough of a character to imagine a series of films about, and his gimmick really is dumb as a rock, but Kinski makes him fun to watch this one time without really doing much -- only just enough.

Wednesday, December 19, 2018

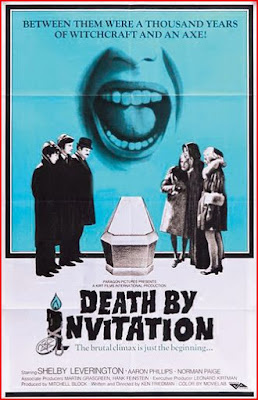

DVR Diary: DEATH BY INVITATION (1971)

On the evidence of Death By Invitation alone I would have dismissed writer-director Ken Friedman as a poor man's Andy Milligan, which is saying quite a bit as far as poverty is concerned. There's a strong resemblance when it comes to subject matter and overall aesthetic sense, but Friedman's oddity, recently featured on TCM Underground, was only the first stage of a career that continues to this day. He's mostly been a writer, most recently collaborating on a yet-to-be released documentary about the hip-hop performer T.I. His big-screen credits include White Line Fever, Heart Like a Wheel, Johnny Handsome, Cadillac Man and Bad Girls. The last-mentioned film, a 1994 western suggests some continuity of concern with Death By Invitation, as it involves violent female empowerment and is pretty dumb. As a director Friedman did only one other film, which probably was wise.

Young and ambitious, Friedman made a film about revenge across the centuries. It opens with unconvincing scenes of 17th century New Netherland, where a woman is tried and condemned for witchcraft to the accompaniment of a loud heartbeat. We cut abruptly to the present day, where a distant descendant of the lead accuser (Aaron Phillips) -- you can tell because they look alike -- presides bibulously over the Vroot family dinner. Arriving late is family friend Lise (Shelby Leverington), who bears a strong resemblance in turn to the accused witch of yore. She entices young Roger to meet her later at her apartment -- despite the father's warning that he shouldn't hang out with "any of those way-out people" -- where she tells a strange story that deserves to be quoted in full, since it's the highlight of the film. Imagine the following told in a spaced-out monotone, like the incantation it apparently is:

Now that's a come-hither speech, and it works! Roger can't resist approaching this alluring and long-winded bacchant, and of course he gets what's coming to him, to the extent that Friedman's budget can visualize it. Practically speaking this means we get a shot of Roger from the neck down as several streams of blood begin to flow down his naked back. Lise's plan, you may not be surprised to learn, is to work her way through the Vroots, killing them indiscriminately, the women as well as the men. She takes out two daughters at once, though one is more or less accidental, the younger girl recoiling from the sight of her elder sister getting decapitated until she falls down a flight of stairs and brains herself. While synopses usually describe Lise as a descendant of the accused woman of the past, her slip of the tongue during her speech raises the possibility that she somehow is the fiend herself, though we have only the word of the accusers that that woman did anything wrong. In any event, while the local police are helpless to stop here -- they're comedy relief figures out of a 1940s B-movie -- Lise has not reckoned on another family friend, Jake (Norman Parker), whose virility overcomes her power. At the climax she tries repeatedly, in increasingly pathetic fashion, to repeat her Southern Tribes speech, as if she needs it to get sufficiently worked up, only to have Jake interrupt her repeatedly with his own come-ons, until old Peter Vroot charges in trying to finish what his ancestor started. Parker and Phillips share what might be, in spite of everything else, this film's strangest scene when Jake visits Peter at his office. Peter Vroot likes his Muzak, apparently, and has the stuff cranked up so loudly -- I recognized one familiar theme from a Tom and Jerry cartoon -- that he and Jake have to yell in order to hear each other in Peter's allegedly impressive sanctum sanctorum. You could believe that Friedman had the music playing on the set, and it may even be possible that he meant this to be funny. If so, it'd be one of those rare and serendipitous moments when a comedy scene is unintentionally funny. Some may say the whole film is that way, but that Southern Tribes bit is genuinely jaw-dropping and could well stop the snarkiest viewer in his or her tracks. To my shame, I found myself wishing that Friedman had had the means to put that story on film, though such a film probably wouldn't be something I could review here.

Young and ambitious, Friedman made a film about revenge across the centuries. It opens with unconvincing scenes of 17th century New Netherland, where a woman is tried and condemned for witchcraft to the accompaniment of a loud heartbeat. We cut abruptly to the present day, where a distant descendant of the lead accuser (Aaron Phillips) -- you can tell because they look alike -- presides bibulously over the Vroot family dinner. Arriving late is family friend Lise (Shelby Leverington), who bears a strong resemblance in turn to the accused witch of yore. She entices young Roger to meet her later at her apartment -- despite the father's warning that he shouldn't hang out with "any of those way-out people" -- where she tells a strange story that deserves to be quoted in full, since it's the highlight of the film. Imagine the following told in a spaced-out monotone, like the incantation it apparently is:

Roger, do you know of the Southern Tribes? Well, it was the common practice for one certain tribe that the women were the hunters, while the men were domesticated. When the village needed food, the women would go out and hunt for it. The men on the other hand were allowed to grease [pronounced "greeze"] the women's bodies before the hunt, but they were never allowed off their knees while massaging the oil into the women. When a band of women found a prey, they would rush at it together, all stabbing wildly with their knives, until the blood of the animal flowed upon their bodies, often mixing with their own blood. Then without knives they would rip away at the flesh of the animal with their hands and mouths. They would rub their bodies against the ravaged animal, against his head, against his genitals, and after they had completely satisfied themselves upon the animal and upon each other they would drag the remains back to the men. Now the men would grovel on the ground when the women returned, exposing themselves, hoping to be chosen, for if they were chosen, and if they were good, they were given food.

[Lights cigarette]

But it happened once that one certain man found that he could hunt in the woods and bring in more food than the women could, and that with his rather large body he could satisfy four or more husbands. And with this man as their leader the men began to ignore the women, disobey their commands. They found they no longer needed the women. Whereupon the women came together and met, and they ["greezed"] and oiled their own bodies and they prepared to hunt that man, naked. We were -- they were naked. They tracked that man in the woods until they came upon him in the clearing. They fell upon him at once, ripping him open and eating his insides. The men were made to watch. They drank his blood and they chewed his bones until all of him was inside of them, but strangely they had raised themselves to passions far beyond their belief, and still writhing with pleasure and desire they fell upon the other men one by one, ripping them open and devouring them all.

Now that's a come-hither speech, and it works! Roger can't resist approaching this alluring and long-winded bacchant, and of course he gets what's coming to him, to the extent that Friedman's budget can visualize it. Practically speaking this means we get a shot of Roger from the neck down as several streams of blood begin to flow down his naked back. Lise's plan, you may not be surprised to learn, is to work her way through the Vroots, killing them indiscriminately, the women as well as the men. She takes out two daughters at once, though one is more or less accidental, the younger girl recoiling from the sight of her elder sister getting decapitated until she falls down a flight of stairs and brains herself. While synopses usually describe Lise as a descendant of the accused woman of the past, her slip of the tongue during her speech raises the possibility that she somehow is the fiend herself, though we have only the word of the accusers that that woman did anything wrong. In any event, while the local police are helpless to stop here -- they're comedy relief figures out of a 1940s B-movie -- Lise has not reckoned on another family friend, Jake (Norman Parker), whose virility overcomes her power. At the climax she tries repeatedly, in increasingly pathetic fashion, to repeat her Southern Tribes speech, as if she needs it to get sufficiently worked up, only to have Jake interrupt her repeatedly with his own come-ons, until old Peter Vroot charges in trying to finish what his ancestor started. Parker and Phillips share what might be, in spite of everything else, this film's strangest scene when Jake visits Peter at his office. Peter Vroot likes his Muzak, apparently, and has the stuff cranked up so loudly -- I recognized one familiar theme from a Tom and Jerry cartoon -- that he and Jake have to yell in order to hear each other in Peter's allegedly impressive sanctum sanctorum. You could believe that Friedman had the music playing on the set, and it may even be possible that he meant this to be funny. If so, it'd be one of those rare and serendipitous moments when a comedy scene is unintentionally funny. Some may say the whole film is that way, but that Southern Tribes bit is genuinely jaw-dropping and could well stop the snarkiest viewer in his or her tracks. To my shame, I found myself wishing that Friedman had had the means to put that story on film, though such a film probably wouldn't be something I could review here.

Sunday, November 4, 2018

THE OTHER SIDE OF THE WIND (1970 - 2018)

Updated on November 5 after watching the accompanying Netflix documentary,

They'll Love Me When I'm Dead.

Orson Welles and Netflix might have been a perfect match. There wouldn't have been any worries about how many paid admissions each project of his could draw, and they wouldn't have depended on him overmuch to attract new subscribers. All that would have mattered, presumably, was how much money he spent and when he delivered the product. Of course, what sort of product he proposed to deliver would make a lot of difference. Batting out something like F for Fake on a relatively regular basis might not have been much of a problem. A narrative film, alas, would have been a different story.They'll Love Me When I'm Dead.

It's interesting that Welles brings up Hemingway in this picture, since it reminded me of some things Hemingway said. Hemingway said of F. Scott Fitzgerald's unfinished The Last Tycoon that the it was no masterpiece in the making, but that it showed that Fitzgerald had just enough skill to keep publishers interested enough to advance him more money. Of a Norman Mailer novel -- The Deer Park, if I recall right -- Hemingway said that the author had blown the whistle on himself. In The Other Side of the Wind, Welles portrays his director protagonist (John Huston) as a Hemingway type, if not more obviously a darker version of himself. Wind, however, is an attempt at what Hemingway, describing his own efforts, called a bank shot, touching several thematic bases at once. It's a work of self-criticism to an extent but also a satire of the whole cult of the director, almost as contemptuous toward "cineastes" (a repeated sneer-word here) as those filmmakers of the generation before Welles who hated (or affected to hate) analyzing their careers. It could be seen equally as an indictment of the creative bankruptcy of auteurism or a confession of Welles's own creative bankruptcy.

The way he tells the story clearly interests Welles more than the story he tells. That story, based on what Frank Marshall, Peter Bogdanovich and others have salvaged from the surviving footage, attempts to account for the creative exhaustion of the Huston character, Jake Hannaford, who's showing excerpts of his in-progress production "The Other Side of the Wind" at a birthday party in the hope of raising the funds needed to finish the project -- much as Welles himself screened scenes at his AFI lifetime achievement award ceremony. The film within the film is both to some extent a parody of Zabriskie Point and a way for Welles to show what he can do visually in color and widescreen. A man stalks and courts a mysterious woman (who may be a terrorist) who goes about naked a lot (Oja Kodar) and torments the man in many ways. They wander through an old move backlot before she meets such fate as she has in the desert. As a commercial project it seems hopeless, but what's specifically stalled it is Hannaford's falling out with his neophyte star, Johnny Dale (Bob Random). The director made a project of the young man, apparently a drifter, after rescuing him from an apparent suicide attempt, but became suspicious of his authenticity. Dale turned out to be a boarding-school dropout involved in some sort of homosexual scandal. Hannaford tormented him on the set of the movie until Dale stormed off, buck naked, after a scene that teased his castration. His departure, and a failure of funding, has let the film a confused jumble, and it's unclear that any amount of money, in the absence of the original inspiration, can solve its problems.