Preceding Little Caesar into theaters by several weeks, John G. Adolfi's Sinners' Holiday arguably marks the beginning not only of the fabled Warner Bros. gangster genre but of "Warner Bros." itself as an archetype or style rather than a mere studio. It's the first film pairing of James Cagney, whose film debut this was, and Joan Blondell, making only her second feature film, and they instantly make it recognizable as a "Warner Bros." film in a way many studio releases of the same year aren't. Blondell and Cagney came to Hollywood to recreate the roles they played on Broadway, when the play was known as Penny Arcade and an appreciative Al Jolson, Warners' big musical star, was in the audience. They are not the primary characters, though Cagney plays a pivotal role. They seem immediately at home in a milieu of cynical, hard-boiled fast talk that soon would define the studio product. That milieu is a boardwalk full of carny attractions, including the once-titular arcade operated by Ma Delano (Lucille LaVerne). Cagney's her youngest, Harry, and the role reminds me of Kirk Douglas in some of his earliest pictures when he might have been typed as a weasel. Keeping his voice at a high pitch, Cagney plays Harry as the sort of physical, mental and moral weakling moral experts then assumed gangsters to be; watching this, you understand why he was cast initially as the sidekick in The Public Enemy. While his Ma thinks him a good boy, Harry hangs out in pool halls, sucking up to Mitch (Warren Hymer), a bootlegger who runs some of the boardwalk concessions. The actual main character of the film is Angel (Grant Withers), an ex-con barker fired by Mitch and hired by Ma Delano to repair her arcade machines. She can use Angel but doesn't trust him, and she definitely doesn't want him hanging around her daughter Jennie (Evalyn Knapp). Harry has a crush on Myrtle (Blondell), a small-time gold digger, and an unlikely rival for her attentions in Happy (Hank Mann, Chaplin's opponent in the City Lights boxing match and quite adept in talkies.), another boardwalk carny.

The main plot kicks in when Mitch is pinched and has to serve time. Harry takes a chance and takes over the bootlegging operation, explaining his new wealth to his ma with vague remarks. When Mitch gets out he's out to get Harry, who shoots his erstwhile mentor in panic during a threatening confrontation. Jennie has seen the shooting but keeps silent as the cops start investigating. Suspicion swirls circumstantially around Angel, while Harry bribes Myrtle into providing an alibi for him. Ma starts to notice the holes in the stories Harry's telling, and doesn't like the way Myrtle is flaunting an apparent new power over her boy. Under pressure, Harry cracks in Cagney's big scene on both stage and screen. Blubbering like a baby, Harry begs Ma to cover for him. Still hostile to Angel, Ma agrees to help frame him for the killing, not realizing how easily Jennie can destroy their plan....

The stage is set for a tragic family showdown, but at the supreme moment Sinner's Holiday simply runs out of gas. The trap is almost shut around Angel when Jennie turns on her mother and brother. When she spills, we'd expect, after seeing Cagney's abject antics earlier, to see Harry have another breakdown, or attempt a breakout and go out like Cody Jarrett, a role for whom in some ways Harry Delano seems like a rough draft. But no, none of the above: once Jennie rats him out he surrenders instantly and dispassionately, like a good loser, consoling Ma by telling her, "You tried." This scene practically defines "anticlimax." The ultimate disappointment probably explains why Sinners' Holiday isn't as well remembered or regarded as its place in history might lead you to expect. Nevertheless, it's an indisputable milestone in the evolution of Warner Bros., with Cagney and Blondell -- aided admirably by the underrated Withers -- virtually creating a cinematic world before our eyes, or at least beginning the process.

A randomly comprehensive survey of extraordinary movie experiences from the art house to the grindhouse, featuring the good, the bad, the ugly, but not the boring or the banal.

Showing posts with label Cagney. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Cagney. Show all posts

Wednesday, June 29, 2016

Sunday, January 25, 2015

DVR Diary: THE OKLAHOMA KID (1939)

A certain irreverence toward the western may have hurt Cagney with contemporary audiences

As a western, it's an archetypal town-tamer story that looks forward to the sort of reluctant-hero roles Bogart would play when he got the chance. Here Bogart (as the purply-named Whip McCord) leads a gang of gamblers and bandits who are robbed by Cagney after they rob a stage. The Oklahoma Kid -- no one knows him by any other name -- has returned to his native ground to witness the famous Land Rush. Like both versions of Cimarron, Kid makes the blunder of staging this tremendous action scene -- though the action here admittedly isn't so tremendous -- very early in the picture. Bogart's gang are "Sooners" who've jumped the claim of the patriarchal John Kincaid, who'd planned to build a town there. Bogart promptly surrenders his claim, however, on the condition that Kincaid cede him exclusive gambling rights in the new town. Meanwhile, the Kid has sat out the land rush in a saloon, explaining to whoever has time to listen that the whole enterprise is futile. Those who play by the rules now will lose out to the strong, he says, and the strong will lose out to the clever in the end. He has to flee to Mexico after killing one of Bogart's men, and once he returns the town is booming but in ways Kincaid never wanted. The old man's accommodation with Whip McCord can't last much longer, despite the good faith efforts of Judge Hardwick (Donald Crisp), his daughter Jane (Rosemary Lane) and Hardwick's law partner Alec Martin (Charles Middleton in a good-guy role). Bogart concocts a plan to frame Kincaid for murder, trick Hardwick into leaving town, and have his judicial pawn railroad Kincaid to the gallows. Despite the efforts of Jane and the Kid, who has finally let on that he's John Kincaid's black-sheep son, the old man is lynched, hung from a second-story porch. This would seem to prove the Kid's earlier point, but now that it's personal he's not so complacent.

Cagney is Cagney here, and if you can't see him as a westerner I can't help you with this film. There are plenty of characteristic moments, from his forcing a saloon pianist to play "I Don't Want to Play in Your Yard" at gunpoint to his showoff singing of "Rockabye Baby" in Spanish. Oklahoma Kid isn't a great western by any stretch, but it's no more a category error than Frisco Kid was, and as a Cagney vehicle it's perfectly acceptable. Bogart gives his stock 1938-40 villain performance and if you've seen one of those you've really seen them all. He'd return to westerns well before Cagney did, stuck between Flynn and Randolph Scott in Virginia City, but the closest he came to the genre after achieving real stardom was the modern-dress Treasure of the Sierra Madre. Bacon directs competently but you can't quite shake a feeling that, despite Cagney, Warners considered this a second-class project compared to Dodge City, the latter getting Technicolor while Kid goes without. The idea that Kid is a second-class western, at most, may have started right there, but while it really is a second-class western, it could be a lot worse, and it's actually a lot better than its dire reputation -- built perhaps on sight-unseen judgments -- would suggest.

Saturday, November 22, 2014

DVR Diary: FRISCO KID (1935)

Cagney is Bat Morgan, a simple sailor but smart enough to spurn the mickey slipped his way by the infamous hook-handed Shanghai Duck, yet not swift enough to avoid a blow to the head intended to induct him into involuntary nautical service. He manages to escape after coming to and is fished out of the ocean by the benevolent Sol Green (George E. Stone). Bat gets revenge on one of Shanghai's minions with a table leg and finally beats the Duck himself to death in Ricardo Cortez's casino. Now a sort of celebrity, he decides to muscle in on the gambling racket all along the infamous coast. His strategy is to start at the top, convincing the local political boss to join him as a silent partner in all the joints. They'll offer protection when the town's crusading journalists call for a crackdown, in return for a fair cut of the profits. Only Spider Burke (Barton MacLane), an old crony of Shanghai Duck, rejects the plan; he's still out to kill Morgan, but his bullet takes out Sol Green instead. The film then shows us a dead Burke on the wharf; while we must assume that Morgan killed him, Bacon doesn't want to show the deed. The Code may have frowned on what would have been premeditated murder rather than a death struggle in self-defense like the fight with Shanghai Duck.

Bat Morgan's rise to power is complicated by his blossoming relationship with one of the reformers, crusading newspaper publisher Jean Barrat (Margaret Lindsay). At first Bat assumes that she's spoken for by her editorial writer (Donald Woods), but she must have something for the bad boys, or else she sees the good in our antihero. As her love for Bat becomes more obvious, her social circle frowns on the relationship and snubs Morgan. To show up the snobs Bat leads a contingent of Barbary Coast gamblers who crash the opening night of a new opera house, and from here things go downhill. The temperamental Cortez resents an insult from the same old fogey of a judge who had snubbed Bat earlier. Unlike Bat, Cortez shoots the judge. This provokes a virtual civil war in San Francisco as the establishment forms a vigilante army -- not for the first time, we're told -- to purge the Barbary Coast. Cortez and Bat's political sponsor -- who has shot the editorial writer in the back -- are captured, tried in kangaroo court and hung by the neck from upper-floor windows. The remaining gamblers are prepared to turn Bat's deluxe casino into their own private Alamo, but Morgan no longer sees any reason for futile violence when defeat is certain.

Frisco Kid seems like it should have fit the town-tamer mode of classic westerns, but it never quite gets there. Instead, it follows the rise-and-fall pattern set for Cagney by Public Enemy, though it aborts the fall with an act of grace. It can't be a town-tamer movie because Cagney's character doesn't reform in time to play that role. Instead, his own taming is the film's ultimate subject. He's effectively tamed by superior force, and the power of the vigilantes is the part most reminiscent of Pre-Code movies, but the real moral influence is that of the good woman, Jean. If Bat Morgan is to survive, he must submit to her tutelage; he's alive at the end of the picture only because she offered to "sponsor" him, after she persuaded the vigilantes to spare him by showing that he had urged the gamblers to surrender, only to get shot in the back by one of them and trampled in the ensuing melee. James Cagney was arguably Pre-Code cinema personified (male division), the original glorified gangster, and by putting him through this sort of auto-da-fe Warner Bros., erstwhile alleged glorifier of gangsters, presumably showed contrition for its own recent vices and promised, through him, to be good from now on, now that the Warners themselves had been impressed by the power of an outraged citizenry the year before. I'm not sure if this was Cagney's first period piece picture, but it's definitely a way to say that the Cagney audiences knew would now be a thing of the past. Cagney is fine here, but his role suffers from the lack of a strong antagonist who lasts the whole picture through. Since he's the tamed rather than the tamer, there's no one for him to tame after Shanghai Duck and Spider Burke are eliminated. The Cortez character seems designed to play the wicked-gambler role in the town-tamer archetype, but he never becomes an antagonist to Cagney and gets relatively little to do apart from a great moment killing the judge and his nicely underplayed stoic resignation ("You win. I pass.") in the face of the lynchers. Apart from Cagney's charisma, Lloyd Bacon's direction and Sol Polito's cinematography are the main things that keep Frisco Kid entertaining. The first reel in particular is a showcase for Polito's illuminating imagery of light in darkness, from the feeble shafts penetrating Shanghai Duck's dungeon to the moonlight reflected from the water playing on the wood of the wharf. Later, Bacon's wrangling of hundreds of extras forming the vigilante army comes to the fore in this film's equivalent of Scorsese's draft riot in Gangs of New York. Some contemporary critics considered Frisco Kid a better film than Barbary Coast -- where the villain was Warner's other super-gangster, Edward G. Robinson -- and having seen them both now I'm inclined to agree. Neither film is a great one, but Frisco Kid is a fine piece of film craftsmanship and, depending on how you look at it, a symbolically significant film marking the change from an era of freedom to one of less, even if it's forced to call this a happy ending.

Friday, September 26, 2014

Pre-Code Parade: BLONDE CRAZY (1931)

As in many early starring roles, Cagney dances on the border of obnoxiousness with his brash aggression, and almost tumbles off the edge every time he calls Ann or others, "Hunnnn-nee!" in an exaggerated drawl. He redeems himself by making clear that Bert isn't as smart as he thinks he is -- he's right in that border zone that lets others underestimate him after taking advantage of him. As usual, Blondell complements him neatly while showing some Pre-Code flesh in a bathtub scene. Overall, this rarity among Cagney's early films -- shown this month on Turner Classic Movies, it hasn't yet had a DVD release -- is a fast-moving affair that actually seems to end too fast. Del Ruth directs at a whiplash pace, transitioning as often as not with sharp cuts rather than dissolves, with seeming loose ends trailing behind. You expect Calhern's character to make a comeback after he vows revenge on Bert, but that moment's the last we see of him. The final scene, with a wounded, jailed Cagney finally assured of Blondell's love, doesn't feel final -- certainly not by the brutal standard of Public Enemy and other early gangster-cycle films. It has a throwaway quality (and one more "Hunnnn-nee!") that left me feeling there was more story to be told -- or else that it was a second-thought happy ending, as if Bert was supposed to die in the trap Milland set for him. It wouldn't have been much of a comedy in that case, and Cagney's films in the wake of Public Enemy are comic more often than not. Did people find that film funny? I doubt it, but they probably wanted to see Cagney win thereafter, and by that standard Blonde Crazy is a split decision: he gets the girl but has to do time before he can have her. It still feels like they missed the last note, that Warner Bros. was still learning what to do with their new star. They'd learn soon enough.

Labels:

1930s,

Cagney,

pre-Code,

U.S.,

Warner Bros.

Tuesday, July 22, 2014

Pre-Code Parade: HARD TO HANDLE (1933)

James Cagney had been absent from first-run screens for seven months when Mervyn LeRoy's comedy opened in January 1933. Back when studios churned out features assembly-line style, that was a noteworthy layoff. Fans knew that Cagney had had a contract dispute with Warner Bros. and had walked off the lot. Hard to Handle was his first film under a new deal befitting his stardom. To some extent, it's also an essay on Cagney's star quality. What makes him a "red-headed sex menace," in the ad's words? It may have been his masterful virility and cocky courage, but in this picture Cagney spends a lot of time running from angry people, when he's not exiting a scene babbling like a madman. He's as much huckster as hustler as Lefty Merrill, introduced as the co-promoter of a dance marathon. Pre-Code cinema in a nutshell: what later generations portrayed as tragic exploitation, as literature would do this same decade -- The novel They Shoot Horses, Don't They? was published in 1935 -- Hard to Handle treats as a joke. Allan Jenkins is the master of ceremonies, regrettably present only in this sequence, and yet you can imagine the same patter coming out of Gig Young's mouth in the They Shoot Horses movie from 1969. Lefty's girlfriend Ruth (Mary Brian) is dancing in one of the two surviving couples while Jenkins introduces her mother Lil (Ruth Donnelly) as a brave but pitiful widow, while Lil leads the applause for herself, striking a boxer's victory pose even before Ruth and her partner prevail. That's a thousand-dollar payday, only Lefty's partner has run off with all the proceeds, leaving Lefty to flee an enraged mob of temp employees expecting their pay, not to mention Lil expecting hers. Ruth feels differently, though, and their feelings toward Lefty reflect their conflicts with each other. Lil can't stand Lefty if he isn't successful; she'd rather match Ruth with society photographer John Hayden (an uncredited Gavin "Lord Byron" Gordon from Bride of Frankenstein). Whenever Lefty's fortunes change for the better, Lil practically pushes Ruth back into his arms while giving poor Hayden the brush-off. Yet a successful Lefty seems to repel Ruth, and not just because that's what Lil wants for her. She likes the scrappy energy he displays as an underdog; a successful, established Lefty might be boring by comparison.

James Cagney had been absent from first-run screens for seven months when Mervyn LeRoy's comedy opened in January 1933. Back when studios churned out features assembly-line style, that was a noteworthy layoff. Fans knew that Cagney had had a contract dispute with Warner Bros. and had walked off the lot. Hard to Handle was his first film under a new deal befitting his stardom. To some extent, it's also an essay on Cagney's star quality. What makes him a "red-headed sex menace," in the ad's words? It may have been his masterful virility and cocky courage, but in this picture Cagney spends a lot of time running from angry people, when he's not exiting a scene babbling like a madman. He's as much huckster as hustler as Lefty Merrill, introduced as the co-promoter of a dance marathon. Pre-Code cinema in a nutshell: what later generations portrayed as tragic exploitation, as literature would do this same decade -- The novel They Shoot Horses, Don't They? was published in 1935 -- Hard to Handle treats as a joke. Allan Jenkins is the master of ceremonies, regrettably present only in this sequence, and yet you can imagine the same patter coming out of Gig Young's mouth in the They Shoot Horses movie from 1969. Lefty's girlfriend Ruth (Mary Brian) is dancing in one of the two surviving couples while Jenkins introduces her mother Lil (Ruth Donnelly) as a brave but pitiful widow, while Lil leads the applause for herself, striking a boxer's victory pose even before Ruth and her partner prevail. That's a thousand-dollar payday, only Lefty's partner has run off with all the proceeds, leaving Lefty to flee an enraged mob of temp employees expecting their pay, not to mention Lil expecting hers. Ruth feels differently, though, and their feelings toward Lefty reflect their conflicts with each other. Lil can't stand Lefty if he isn't successful; she'd rather match Ruth with society photographer John Hayden (an uncredited Gavin "Lord Byron" Gordon from Bride of Frankenstein). Whenever Lefty's fortunes change for the better, Lil practically pushes Ruth back into his arms while giving poor Hayden the brush-off. Yet a successful Lefty seems to repel Ruth, and not just because that's what Lil wants for her. She likes the scrappy energy he displays as an underdog; a successful, established Lefty might be boring by comparison.Ruth doesn't have too much to worry about on that score. Hard to Handle consists of a succession of Lefty's get-rich quick schemes, all essentially hare-brained but some more successful than others. The most catastrophic is his plan to stage a treasure hunt at an amusement pier, with $1,000 in bills hid among the concessions. "THERE IS NO DEPRESSION" at the pier, his ads proclaim, but as a mob demolishes everything in sight Lefty's partners reveal that they've only planted two five-dollar bills in the entire place. Soon enough, Lefty's on the run again, but his gift of gab gets him back in the game soon enough. Ruth's frustration with ill-made cold cream gives him an idea; seeing her exert herself in vain rubbing it into her skin, he realizes that the slop would make a great reducing cream simply because people would work so hard rubbing it on themselves. "It won't rub in! It won't rub in!" he screams maniacally as he dashes off in search of fresh fortune. After some hard bargaining to win a society maven's endorsement, Lefty becomes a successful public-relations man and the apple of Lil's eye, if not Ruth's. But if Lefty is still basically a con man, he's not the biggest or the canniest of the lot. He's soon bamboozled by a father-daughter team into promoting Grapefruit Acres, a tract of land in Florida, little realizing that there's no way anyone can make the money the promoters promise growing grapefruit. By the time this sinks in for our hero, his clients have skedaddled to Rio and he's left holding the bag. But by one of those coincidences that are the stuff of popular cinema, who should share his cell but his erstwhile partner from the dance marathon. After greeting him with a punch in the jaw -- his only act of real violence in the picture -- Lefty chats him up as if nothing serious had happened ("So how are you?") and notices his slimmer figure. How did he get that way? Why, it was a grapefruit diet! Cue the maniacal laughter again as Lefty figures out how to make good on Grapefruit Acres -- but after his crowning success he needs to pull off one more con to win Ruth, ever unimpressed by success, for good.

Some are determined to see this talk of grapefruit as an in-joke on the star of The Public Enemy, but whatever Pre-Code is, I don't think it's as in-jokey as today. In any event, Lefty Merrill is a Cagney virtually free of Public Enemy's thuggishness, more rascal or even mountebank than "menace" of any sort. He's a safer if not necessarily more scrupulous Cagney, with just enough transgressive brazenness to maintain his original appeal. We'll see this Cagney periodically for the rest of his career proper, culminating in his Coca-Cola salesman in Billy Wilder's One Two Three. The depression note of desperation adds to the fun of his mania in Hard to Handle, but I'm not sure if the huckster mode shows Cagney at his best. It does prove him an entertaining if overpowering comic actor -- and I think overpowering was what everyone was looking for.

Sunday, May 18, 2014

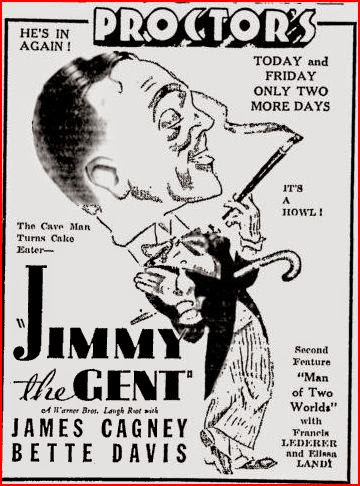

Pre-Code Parade: JIMMY THE GENT (1934)

The fugitive (Arthur Hohl) actually killed his man in self-defense, but an angry girlfriend (Mayo Methot) is determined to testify against him. Jimmy's mission is to make sure that Monty Barton can inherit his fortune and enjoy it as a free man, minus the 50% Jimmy will claim. The key is to neutralize the girlfriend. That can be done by getting her to marry Monty, since these are still the good old days when a wife is not allowed to testify against her husband in court. But Jimmy doesn't want to cut the girlfriend in on Monty's money. So before he makes his move on her he press-gangs Louie's dimwitted girlfriend (Alice White) to marry Monty before a justice of the peace. Then, keeping this secret, he convinces Monty's girl that she'll get a fortune if she marries Monty and effectively acquits him. Later, he'll be able to cut her out by saying the marriage was illegitimate. In case Louie's girl gets any ideas, Jimmy has her marry Monty under a false name, so her marriage won't be legitimate, either. It's actually a pretty brilliant scheme, and it works, but it all turns to ashes for Jimmy when Louie blabs about it to Joan, thus destroying the image of a reformed Jimmy that the title gent had tried to cultivate.

To atone, Jimmy makes a grand gesture of self-sacrifice. He goes to Wallington's office and surrenders his share of Monty's inheritance to his rival so it can go to the granddaughter. As it turns out, Jimmy has smelt a rat for some time. Wallington had been making romantic moves on Joan for a while, but now that he has a big payday he moves to ditch her and take a steamer across the Atlantic alone. Jimmy manipulates everyone so Joan will catch Wallington on the ship and after the requisite brawl -- much of it happening behind a closed bathroom door -- our hero gets the girl. The problem with all this is that Jimmy Corrigan is one of the most unlikable characters Cagney ever played. He never ceases to be a ruthless self-serving manipulator and a thug at heart, but there's little charm or even charisma to compensate for that. There's no reason to root for him except that he's Jimmy Cagney, and that might be enough if he really were the sort of cartoon character he seems to be here, but I think audiences knew better and I hope they recognized this as second-rate Cagney, as Cagney himself apparently did.

The trailer doesn't play the "gent" angle up so much and thus sells the picture more accurately. It's from TCM.com, of course.

Saturday, April 12, 2014

Pre-Code Parade: HE WAS HER MAN (1934)

In 1938 James Cagney returned to Warner Bros. after a two-year exile and made Angels With Dirty Faces. That film has one of cinema's most famously ambiguous endings. Cagney's con is going to the chair and is determined to put a brave face on. Pat O'Brien as his old pal the priest urges him to put on a different act: no matter how he really feels, he should pretend to die a coward so the Dead End Kids won't make a role model of him. Cagney refuses -- but in the actual death chamber he does exactly what O'Brien wanted. The question remains: did he have a change of mind or heart, or did he actually crack at the sight of the chair. However you interpret it, what seems beyond dispute is that playing the coward is the right thing for a gangster to do under the circumstances. Angels is a product of the Code Enforcement era; we need to go back to Pre-Code to understand better the significance of Cagney's performance.

In 1938 James Cagney returned to Warner Bros. after a two-year exile and made Angels With Dirty Faces. That film has one of cinema's most famously ambiguous endings. Cagney's con is going to the chair and is determined to put a brave face on. Pat O'Brien as his old pal the priest urges him to put on a different act: no matter how he really feels, he should pretend to die a coward so the Dead End Kids won't make a role model of him. Cagney refuses -- but in the actual death chamber he does exactly what O'Brien wanted. The question remains: did he have a change of mind or heart, or did he actually crack at the sight of the chair. However you interpret it, what seems beyond dispute is that playing the coward is the right thing for a gangster to do under the circumstances. Angels is a product of the Code Enforcement era; we need to go back to Pre-Code to understand better the significance of Cagney's performance.Lloyd Bacon's He Was Her Man is one of Cagney's most obscure films. It shouldn't really be obscure given that it's a Warner Bros. gangster film teaming Cagney with frequent co-star and arguable female counterpart Joan Blondell. But it doesn't seem to be discussed much compared to the other Cagney films of the period. Is it so much worse? Having seen it finally, I don't think so, but it is different in mood from Cagney's contemporary pictures, in some ways looking ahead to noir and in some ways looking back to the melodrama of renunciation. Yet at the time of its release in June 1934 some critics saw this picture as one of the straws that broke the camel's back. For such a low-key movie as it actually is, the reaction seems excessive.

In one of the rare appearances of Cagney's moustache, the star plays Flicker Hayes, an ex-con safecracker who takes up his old profession only to set up his partners, who had set him up years before. Having done that, Flicker has to lay low to avoid mob vengeance. He makes his way to San Francisco and from there to a small California fishing village. On the way he picks up Rose Lawrence (Joan Blondell) after first mistaking her for a finger woman in his Frisco hotel room. Turns out she was the previous occupant and had returned to retrieve a wedding dress she'd secreted between matresses. Rose is a fallen woman who has a future in the fishing village, where a simple "Portugee" fisherman (Victor Jory) loves her. She's falling hard for Flicker, however, while an innocent-seeming tourist fisher (Frank Craven) is actually keeping an eye on Flicker after making him in Frisco until the gunmen can reach town. Flicker feels bad about betraying the friendly Portugee and worse about possibly embroiling Rose in his life of perpetual danger. The inevitable arrives, and the most Flicker can do is figure out a way to spare Rose from sharing his fate.

There's something noirish to the doom hanging over Flicker and the impossibility of escaping it, and in the overall subdued, rueful mood of the movie, not to mention the extensive location work anticipating the more naturalistic noirs. The mood extends to Blondell, who gives as morose a performance as I've ever seen from her. By comparison, as Flicker Cagney strives to keep up a cool front, and what keeps him a hero at the end is his renunciation of Rose to save her life and his ability to maintain his cool in the face of death. The gangsters are about to take Flicker for a ride when Jory's family and others of the wedding party arrive. Jory's mother is horrified because they all forgot the ice cream for the reception, but Cagney and his just-arrived "business partners" agree to pick some up for them. At the end of the ride and the start of a last walk into the wilderness, Flicker reminds his nemeses to pick up that ice cream. They'll have to do it, he tells them, because he's going in the other direction.

In many ways, then, He Was Her Man (an earlier title was Without Honor) hardly feels like a Pre-Code movie, and yet critics of the crisis year 1934 treated it like Exhibit A proving the need of Code Enforcement. For syndicated columnist Dan Thomas, the implicit fornication of Flicker and Rose, while she was betrothed to another man, no less, was but the latest reprise of a theme "that has aroused critics to a feeling that continual recurrence of unmarried love on the screen cannot fail to have a relaxing effect on the morals of the young men and women, giving them a warped view of life and the way it is lived today."

Meanwhile, Cagney's cool in the face of doom infuriated Pittsburgh Press columnist Kaspar Monahan, who saw in it a "glorification of evil." Movie historians are familiar with the critique of Pre-Code crime films for their "glorification" of criminals, however incredible that critique seems when movie gangsters so often end up dead or defeated. Monahan clarifies things a little; for him, "glorification" isn't a matter of rewarding crime but an attitude that romanticizes it and makes it appealing despite defeat in the end. "We witness it in James Cagney's 'He Was Her Man,'" he writes, "for at the end, although the gangster he is playing is put on the spot, he is depicted as going to his death jauntily and steel-nerved. Bunk again -- gangster rats facing certain death squeal, bawl and grovel."

While we might wonder about Monahan's firsthand evidence for his claim, it's clear that he represented a viewpoint that had an obvious influence in years to come. While we shouldn't overestimate institutional memory in the pre-video era, Angels With Dirty Faces now looks a little like a correction of or apology for He Was Her Man on the part of Warner Bros. Whether or not you believe that criminals are essentially "rats," are cowards without their guns, etc., you can't help but feel as if a party line, and not just the Production Code, was being enforced by 1938. That's why some of us regret Code Enforcement even if its sophisticated sublimation had artistic benefits of its own. It's especially regrettable if it meant damning an admirably modest picture like He Was Her Man as propaganda for evil. That makes you wonder whose values were most messed up in 1934.

Here's the original trailer from TCM.com

Labels:

1930s,

Cagney,

pre-Code,

U.S.,

Warner Bros.

Tuesday, September 10, 2013

Pre-Code Parade: THE DOORWAY TO HELL (1930)

It probably didn't seem that way in 1930. Then, Ayres was a young meteor. The year before, at age 21, he was Garbo's love interest in The Kiss. Earlier in 1930 he staked his main claim to cinematic immortality as the star of the World War I blockbuster All Quiet on the Western Front. Ayres seemed set to be huge, but his greatest role may also have proved a curse. The sympathetic German soldier of the war film marked Ayres as a sensitive type; the actor internalized the film's pacifist ethos, derailing his career for a time by declaring himself a conscientious objector during World War II. Already, you suspect, movie audiences may have felt it one thing for Ayres to be the sensitive enemy bemoaning the cruelty of war, and another for him to play a ruthless criminal mastermind.

If you want to fit Doorway to Hell into a gangster subgenre, Al Pacino has the right description for it: "Just when I thought I was out, they drag me back in!" Ayres plays Louie Ricarno, who spends the first act of the film brilliantly consolidating his control over the Chicago underworld and putting it on a "business basis." Having conquered the Windy City, Ricarno is ready to retire. This is a good time to remind you that the man playing him was 22 years old. Initially reluctant to obey him, some of the local hoods are reluctant to see him go. Even his moll Doris (Dorothy Matthews) is reluctant to see him leave the life behind; more to the point, she's reluctant to leave the life -- and Mileaway -- behind.

Mileaway inherits the Chicago setup but can't keep all the factions in line. Gang war resumes, and while Mileaway flounders helplessly, cooler heads think they know how to bring Louie back into the game. They know (because Mileaway blabbed it) that Louie has a younger brother in a military school. They attempt a kidnapping of the kid to force Louie's hand, but they bungle it and the kid gets run over by a truck trying to escape them. The muggs get what they wanted, sort of. Louie's definitely back in the game now, but he's after their hides.

It may read like a conventional crime melodrama, but Doorway to Hell doesn't know where its real story is. They have a triangle of Ayres, Matthews and Cagney but bungle every attempt to wring drama from it. Most importantly, as far as I can tell Louie never catches on to Doris and Mileaway's affair, even though the cop who has a running, bantering relationship with Louie throughout the film has figured it out by looking at a mirror from the right angle. The cop takes advantage of this knowledge to trap Mileaway into making a confession to a crime he didn't commit. Mileaway has an alibi, but can't use it because it would mean admitting his betrayal of Louie. The scene where Mileaway gets grilled is where the film falls irreparably apart. Watching it, I assumed that the cops wanted Mileaway to rat out Louie to save his own skin, but for some reason they really want Mileaway to confess to a crime they know he didn't commit. He thinks he's confessing to spring Louie, as well as to keep the cop quiet about the affair, but the cops are actually holding Louie, and will keep holding him until he stages an escape, on a separate charge. The real drama of the picture should be the triangle, but that would mean giving Mileaway more balls or more of an edge. It would mean doing something sensibly dramatic like having Mileaway decide he wants to keep his power and take Louie's girl. Producer and director had James Cagney in this role and couldn't imagine any of this. They simply didn't know what they had, and producer Darryl F. Zanuck remained ignorant until it was almost too late for Cagney, casting him in a similar subordinate role in The Public Enemy until the early rushes for that picture exposed the error. Doorway to Hell had one point it wanted to make -- that there could never be any getting out of the business for the gangster, and finds the stagiest way to stage it, finishing with Ayres alone in a hideout, albeit with a couple of visitors, somehow checkmated into accepting his fate and walking through the metaphoric portal of the title. In one of those charming little touches of the early gangster film, machine gun fire plays all the way through the epilogue text and the end title card.

Well, the studio had to start somewhere, and Doorway to Hell may have served Warners as a tutorial on how not to make a gangster film. Mayo's direction, at least, is mostly solid, and the film has more of a studio-set expressionist look than some of the early gangster films. If that registers as somehow not looking right, that only reinforces the rough-draft impression Doorway makes. At least that gives it curiosity value, and the film will always be of interest to Cagney fans as a case study of their man paying his dues in a thankless role. Write it off as a learning experience for all involved, and for yourselves, too.

Check out the adorable animated gunfire in the original trailer from TCM.com

Wednesday, July 31, 2013

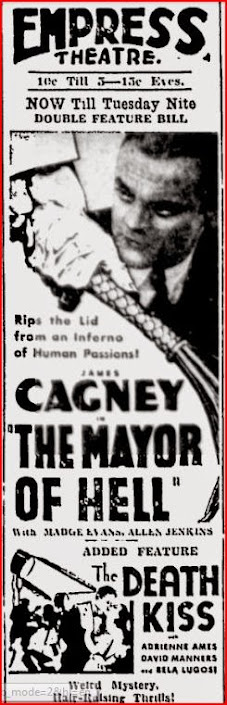

Pre-Code Parade: THE MAYOR OF HELL (1933)

Jimmy Cagney doesn't show up until about 24 minutes into this Archie Mayo picture; until then, it's a Frankie Darro movie. In 1933 the teenaged acting veteran -- he'd been working since 1924 -- got the nearest thing to a big-studio push he'd ever get. Darro would make his biggest mark on Hollywood history later the same year, and also for Warner Bros., in William Wellman's Wild Boys of the Road, though for some audiences he may be best known for his role in the one-of-a-kind Gene Autry sci-fi serial The Phantom Empire from 1935. In 1933 Darro seemed to symbolize youth on the precipice during the Great Depression, a kid whose relatively small stature represented an endangered innocence disguised by a wishful toughness.

Jimmy Cagney doesn't show up until about 24 minutes into this Archie Mayo picture; until then, it's a Frankie Darro movie. In 1933 the teenaged acting veteran -- he'd been working since 1924 -- got the nearest thing to a big-studio push he'd ever get. Darro would make his biggest mark on Hollywood history later the same year, and also for Warner Bros., in William Wellman's Wild Boys of the Road, though for some audiences he may be best known for his role in the one-of-a-kind Gene Autry sci-fi serial The Phantom Empire from 1935. In 1933 Darro seemed to symbolize youth on the precipice during the Great Depression, a kid whose relatively small stature represented an endangered innocence disguised by a wishful toughness. In Mayor of Hell Darro plays Jimmy, the leader of a small, impeccably multicultural street gang. A presumptive WASP, Jimmy consorts easily with Italian, Jewish and black kids -- the last played by Allen Hoskins under his Our Gang name, "Farina." They're petty thieves and extortionists, offering to watch your car for a quarter and vandalizing it if you refuse. They all seem to suffer from inadequate if not absent fathers -- Warners stalwart Robert Barrat appears all-too-briefly as Jimmy's mysteriously bitter dad during a protracted juvenile-court scene (Arthur Byron presiding) after the gang is pinched. Byron nudges the parents into consigning their kids to reform school, apparently not knowing the horror to which he's condemned them.

Jimmy (Frankie Darrow, on the ground above left) blames his dad (Robert Barrat, below center) for his abrupt decline from honor student to juvenile delinquent.

This particular reformatory is run by Thompson (Dudley Digges), a petty tyrant who seems interested only in putting the kids to work. Conditions prove unbearable for Jimmy, who takes advantage of the confusion created by the abrupt arrival of a new deputy state commissioner to attempt an escape. Patsy Gargan (Cagney) is a political appointee, a "ward-heeler" who controls 5,000 votes and wants an undemanding sinecure as compensation. He's breezily indifferent to the responsibilities of his office, expecting Thompson to write his reports for him, until he witnesses Jimmy's escape attempt. The lad doesn't get very far, ending up stuck on a barbed-wire fence as Thompson flogs him until he falls off. Something stirs in Gargan at the sight. Something else stirs when he meets the pretty, conscientious head nurse (Madge Evans), who has progressive theories on reforming delinquent youth. Resenting an inferred slight at his own background when Thompson condemns the kids as slum scum, Patsy resolves to be a hands-on commissioner, implementing many of Nurse Dorothy's ideas, if only at first to remain near her.

Thompson (Dudley Digges) turns squeamish at the thought of drinking from Patsy Gargan's flask, but relishes his work flogging Jimmy.

Dorothy has been reading up on the "boy's republic" idea, already implemented in real life in several states, in which troubled boys build character through self-government. Deposing Thompson and driving out his old guard, Patsy turns the reform school into a model boy's republic, with Jimmy its unlikely president. The boys run their own legal system on egalitarian principles; Farina is seen acting as a defense attorney when a white boy is accused of stealing a candy bar from the new store -- run stereotypically by one of the Jewish kids. The boys eat well and sport snappy new uniforms. But Patsy's past catches up with him as he returns to the city to put down an uprising in his political organization. When the dispute turns into a gunfight, Patsy has to go on the lam, opening the door for the vindictive Thompson to reassert his authority.

Allen Jenkins (above, left) doesn't get enough to do as Cagney's stooge. Cagney gets plenty, of course.

Things grow worse than ever as Thompson forces Dorothy out and cracks down on the most spirited kids, i.e. Jimmy's crew. When a tubercular pal dies after being left in a cold punishment shed overnight, Jimmy is ready for war. Mayor of Hell becomes a characteristic film of its period in its imagination of an apocalyptic uprising as the kids take over the reformatory and subject Thompson to a kangaroo court trial. His escape attempt is as futile as Jimmy's earlier effort, but ends more gruesomely. Driven by the flames of a burning building, Thompson falls off a roof, bounces off the barbed-wire fence and lands ignominiously in a pig pen, where one can imagine what the pigs do with him. When Patsy, rediscovering his responsibility to the boys, arrives to calm the crisis, there's a long moment of tension when it seems possible that the enraged boys may turn on both Patsy and Dorothy, both of whom they assume to have abandoned them to Thompson's tender mercies. But movies allow us to eat our cake and have it too, to imagine the insurrection many in 1933 felt was just around the corner but also to reassure themselves that we can all step back at the urging of a voice of reason, to ensure a happy ending. Mayor of Hell has it both ways, ultimately coming out in favor of law, order and peace but pretty much condoning the hounding of Thompson to his death as an act of justice.

By the time Cagney finally shows up, you get the impression that he's been grafted onto what may have been first imagined as a self-sufficient social-problem film, as Wild Boys of the Road would be. While Cagney gives a fine, charismatic performance, his character's improbably evolution into an idealist may be the weakest part of the film. The boys certainly need a sympathetic friend in a high place like Patsy Gargan, but after the first 20 minutes you get the feeling that Darro, Hoskins et al could have carried this picture by themselves without help from a star as big as Cagney. Strange to say, the star's overpowering presence probably prevents Mayor of Hell from being the kind of definitive Depression document that Wild Boys has become in retrospect. Even so, it captures a bit of the dangerous zeitgeist of 1933 in entertaining fashion.

If it's a Warner Bros. picture, TCM.com has the trailer.

Tuesday, July 30, 2013

Satan and Dusty Shoes: NOW PLAYING, JULY 30, 1933

Now playing in Milwaukee: the devil, himself:

You can see him at the Warner.

Far from evil is Cagney in this picture, however -- as you'll learn when I review it this week.

Elsewhere, here's one of the titles of the year:

Here is a backstage musical from the director of The Mummy and Mad Love. Karl Freund is no Busby Berkeley, but damned if he doesn't try. For the climactic song, "Dusty Shoes," uploaded to YouTube by perfectjazz78, he tries to do "We're In the Money" and "Remember My Forgotten Man" in one number. Check this out.

... All right, then. Elsewhere still ...

You can see him at the Warner.

Far from evil is Cagney in this picture, however -- as you'll learn when I review it this week.

Elsewhere, here's one of the titles of the year:

Here is a backstage musical from the director of The Mummy and Mad Love. Karl Freund is no Busby Berkeley, but damned if he doesn't try. For the climactic song, "Dusty Shoes," uploaded to YouTube by perfectjazz78, he tries to do "We're In the Money" and "Remember My Forgotten Man" in one number. Check this out.

... All right, then. Elsewhere still ...

This last one? It's a Columbia picture, and in the end the pregnant heroine kills herself. Welcome to Pre-Code Cinema!

Saturday, December 8, 2012

Pre-Code Parade: WINNER TAKE ALL (1932)

James Cagney was an unprecedented movie star, a distinctive produce of talkies and Pre-Code cinema, a sexy thug. Think of the tough-guy stars of silent movies, or Cagney's tough-guy peers in the early Thirties: hulking slabs of beef like Wallace Beery or George Bancroft. A certain burliness was expected of film's top brawlers. By comparison, Cagney was a runt, but he made up with ferocity (making "Tarzan look like a sissy") what he lacked in mass. In fact, he overcompensated. Cagney's stardom is impossible today, insofar as violence against women, exemplified by that grapefruit smashing into Mae Clarke's face forever, was a key part of his persona. It was something Depression audiences wanted to see, and I don't think they had something against women. Sexy brutes like Cagney and Clark Gable were the sort of charismatically ruthless survivors -- interestingly, "caveman" was a popular label for them -- that audiences wanted to be or wanted to have in hard times. They were suited for those new hard times in a way many slightly older matinee idols -- John Gilbert, Ramon Novarro, Richard Barthelmess -- weren't. Roy Del Ruth's Cagney vehicle emphasizes the contrast between its star and the older type by showing Cagney the scrapper succumbing to the temptation to become a "powder puff" -- a pejorative associated with Rudolph Valentino, the dead exemplar of the old stardom.

James Cagney was an unprecedented movie star, a distinctive produce of talkies and Pre-Code cinema, a sexy thug. Think of the tough-guy stars of silent movies, or Cagney's tough-guy peers in the early Thirties: hulking slabs of beef like Wallace Beery or George Bancroft. A certain burliness was expected of film's top brawlers. By comparison, Cagney was a runt, but he made up with ferocity (making "Tarzan look like a sissy") what he lacked in mass. In fact, he overcompensated. Cagney's stardom is impossible today, insofar as violence against women, exemplified by that grapefruit smashing into Mae Clarke's face forever, was a key part of his persona. It was something Depression audiences wanted to see, and I don't think they had something against women. Sexy brutes like Cagney and Clark Gable were the sort of charismatically ruthless survivors -- interestingly, "caveman" was a popular label for them -- that audiences wanted to be or wanted to have in hard times. They were suited for those new hard times in a way many slightly older matinee idols -- John Gilbert, Ramon Novarro, Richard Barthelmess -- weren't. Roy Del Ruth's Cagney vehicle emphasizes the contrast between its star and the older type by showing Cagney the scrapper succumbing to the temptation to become a "powder puff" -- a pejorative associated with Rudolph Valentino, the dead exemplar of the old stardom. Introducing Winner Take All on a night dedicated to child actors, TCM host Robert Osborne strained to emphasize Dickie Moore's role in the picture as proof of the influence on Warner Bros. of The Champ, M-G-M's Oscar-winning hit about a boxer and a kid. But Winner is plainly a riff on Cagney's persona, and Moore's role is relatively insignificant and unsentimental. Cagney plays Jim Kane, a contender taking a sabbatical from the ring, implicitly to dry out. We first see him as the beneficiary of a benefit night at the arena, the fight fans throwing money into the ring for him as he makes a halting speech of thanks. He's sent west with a friendly warning from his manager (Guy Kibbee) and his second (Clarence Muse) to lay off the high life and keep out of trouble. In his exile he falls for a young single mother (Marian Nixon) who'd once waitressed at Texas Guinan's legendary nightclub, and takes a tough fight to raise money for her when her insurance company stiffs her. Once word gets out that he's fighting again, Kibbee calls him back to the big city, where his handsome brutality captivates a socialite (Virginia Bruce) who invites him to a high class party and otherwise seduces him. Bruce shows off some seriously low-cut lingerie to get the job done, and our hero soon forgets the mother and son out west.

Not realizing that the socialite is turned on by his freakshow value as a broken-nosed, cauliflower-eared brute, Jim decides that he should make himself more attractive to her and has plastic surgery. To preserve his new good looks, he adopts a dancing defensive style in the ring, winning fights easily but displeasing fans who want a good old-fashioned scrap. His new habits earn him the "powder puff" tag, and Kibbee warns him that he's risking his career. In one tremendous moment, Kibbee shows who's boss by laying out the intractable Cagney with one punch. Still, Jim's determined to do things his way, even when he learns that he's begun to bore the socialite, who walks out on him in mid-fight one night. Desperate to impose his will, he insists that she sit in the front row for his next bout, but learns just as the bell rings that she's taking passage on an ocean liner instead. Learning that he has only 20 minutes to reach the ship and stop her from leaving, he abandons his new style in a hurry to knock his man out as soon as possible. Ruining his new face in the process, he gets the job done and rushes to the docks in his boxing trunks, only to find the socialite trysting with another man. Now knowing the score, he kayoes the interloper, gives the socialite a kick in the rear, and heads home to make his apologies to the little mother from out west, who'd followed him back to New York only to be blown off shortly before. The film ends with adorable little Moore bopping our hero on his bandaged nose.

Winner Take All puts Cagney into some fish-out-of-water situations with predictable results. Asked for his opinion of the Soviet Five-Year Plan, Cagney tells a society gathering that he doesn't trust those installment schemes and always pays in full up front. When a butler laughs at this, Cagney lays him out. Apart from Public Enemy, Cagney was mainly a comic figure in the Pre-Code era, a transgressor who gets away with what we wish we could -- usually smacking the sort of people we wish we could. Again, it says something about the era that his victims so often include women (he gives his niteclub date in the flashback a face full of seltzer water), but it doesn't look like many women objected back then. His violence was essential to his manhood, and Winner underscores this, stressing that it's not merely the physical grace that Cagney was praised for later but his willingness to mix, to put his chin out, get as good as he gives, that defines him. Cagney himself apparently disagreed, and the publicity for Winner acknowledges that it led to conflict between star and studio. Money may have been the provocation -- Cagney didn't like that he was making less money than Dick Powell -- but the actor was also unhappy with the limited range of roles that Winner seemed to enforce. A year later, he was singing and dancing for Busby Berkeley in Footlight Parade, but Winner showcases his dancing skills in the squared circle. The ballyhoo had you believe that Cagney was so convincing as a boxer that you'd assume he'd fought professionally. But Winner's fight scenes are not much less pantomimic or risible than those in City Lights. They don't exactly remind me of period fight films. But they express the idea that Jim Kane is first a nonstop scrapper, then an untouchable dancing master. In any event, the film is a comedy, so we probably should seek pugilistic realism elsewhere. What we have in Winner is a relatively minor Cagney comedy that nevertheless ought to be essential viewing for his fans for the way it struggles to figure out who exactly Jimmy Cagney the movie star persona was: lover, lout, or both.

We can't wrap this up without the original trailer, provided as usual by TCM.com

Sunday, November 6, 2011

Pre-Code Parade: HERE COMES THE NAVY (1934)

Maybe Llyod Bacon's service comedy doesn't belong in the Pre-Code Parade. At the time, this initial team-up of longtime screen partners James Cagney and Pat O'Brien was received as an example of how Cagney, in particular, would be presented in the new era of Production Code enforcement. Here's Dan Thomas writing for the United Press service in July 1934.

Maybe Llyod Bacon's service comedy doesn't belong in the Pre-Code Parade. At the time, this initial team-up of longtime screen partners James Cagney and Pat O'Brien was received as an example of how Cagney, in particular, would be presented in the new era of Production Code enforcement. Here's Dan Thomas writing for the United Press service in July 1934.Passing on to another picture which comes under the new order -- in other words the type of production good for family entertainment -- one finds James Cagney's latest, "Here Comes the Navy." Despite the fact that he is an outstanding hero with kids all over the nation, most of Cagney's films have contained objectionable features. Not so this one, however....It will be films of this type in which you will see Cagney in the future. He'll be hard-boiled, sure, but there will be no more of the gangster or rough on women stuff.Thomas was not a perfect prophet, but he tells us what the Breen Office and its advocates expected from Cagney and his studio from then on. I watched Here Comes the Navy expecting to see the first chapter in the taming of Cagney -- a service comedy seemed an ideal vehicle for that project. But what I saw was a kind of rearguard action by the five-man writing team, a largely successful attempt to keep the transgressive Cagney persona alive while appearing to socialize him.

There are two types of service comedy, at least. There are those about the utter physical incompetents and their struggles with drill and discipline (Shoulder Arms, Buck Privates, etc) and those about the idiosyncratic asshole who learns the value of discipline, honor and patriotism. Tell It To The Marines, a silent movie that earned Lon Chaney Sr. an appointment as an honorary Marine, is the template for the latter kind of service comedy, which I expected Here Comes the Navy to follow, with O'Brien as the gruff mentor who makes a real man (or a "right guy," in the film's own jargon) out of Cagney. Their later Fighting 69th comes closer to the model, but Here Comes the Navy is less a tale of a man mastered by an organization than one about a man mastering an organization.

Cagney plays "Chesty" O'Connor, a civilian contractor at a Navy yard who falls into a feud with O'Brien's naval officer, Biff Martin. O'Connor is some sort of big shot or would-be big shot with the construction workers, spending big dough for the day to give away a loving cup to the winners of a dance contest at a union frolic. He ends up getting into a brawl with O'Brien -- Cagney preserves his dominance by losing only because a girl distracts him. His idea of seeking revenge is to enlist in the Navy, expecting to be assigned immediately to Biff's ship, the doomed USS Arizona, where Bacon filmed some scenes with Navy cooperation. Instead, of course, he's assigned, along with his adoring stooge Droopy (Frank McHugh) to six weeks of basic training -- learning this, Chesty says "I quit" but can't once he's taken the oath. Fortunately for him, he gets assigned to Arizona after finishing basic, and his feud is fired up when he falls for Biff's sister Dorothy (Gloria Stuart).

Chesty's nasty attitude toward Biff extends to the Navy as a whole, and his open contempt for it all, despite friendly warnings from the more sociable Droopy, earns him isolation and the scorn of his fellow sailors, most of whom happen to like Navy life. From this point, one might interpret the remainder of the film as Chesty's attempt to earn the regard of his comrades, but the film lets you interpret things differently as well. Loading shells and powder into Arizona, he sees that some spilled gunpowder has ignited, threatening the entire ship. He throws himself on top of the smoldering powder and smothers it with his own body. He earns the Navy Cross for this, but readily tells anyone who'll listen that he acted primarily to save himself. Within moments of the medal ceremony, he pins the medal on Droopy's chest, in view of the high-ranking officers who'd decorated him, telling his new sailor buddies that he only cares about the bonus that comes with the medal. Before long, at his own request, he's transferred to the airship Macon, another doomed vessel in real life.

In a climax based on a real accident, Arizona's crew, including Biff, is assigned as Macon's ground crew. Due to rough winds, the airship can't dock on its first pass and the ground crew has to quickly let go of the ropes. Biff doesn't let go and is carried high into the air with little likelihood of hanging on long enough to land with the ship. In a happier resolution than in reality, Chesty, without knowing who he's saving and in defiance of orders, has the ingenious notion of shimmying down the rope to the victim and going down together with him and a parachute. They're both beat up by the landing, but before long Biff is using crutches to lead Dorothy to the altar, where Chesty wheels up to join them. Then comes the closing gag: for his creative heroism Chesty has been reassigned to Arizona with a promotion that makes him Biff's superior officer. The man has mastered the system, not the system the man. Cagney shows no sign of being anything different from his arrogant, hard-boiled wiseacre self we've seen all along. He is not tamed or really even disciplined, and we could easily assume that his acts of heroism are matters of pure instinct, innate to his persona, and nothing the Navy taught him. In short, Here Comes the Navy is less a generic service comedy than it is a Jimmy Cagney star vehicle, and the difference between the two, even in the transitional year of 1934, makes Bacon's film more pre-Code than not in spirit, even in the absence of "rough on women stuff." Of course, the scene in which sailors basically accuse Droopy of being gay for Chesty ("What are you, a couple of violets?") helps that impression along, as does an overall irreverence that seems surprising given the Navy's cooperation with the project. Cagney's irrepressible attitude and his interplay with both O'Brien and his fellow "Irish Mafia" member McHugh make this a genuinely funny film. It's cool to see how much Cagney can get away with in a military setting, however unrealistically, and still advance. I assume he wouldn't have gotten away with as much a year or so later, and that assumption entitles him and his film to join the Pre-Code Parade.

The trailer says that "Every sailor is a Don Juan inside." Sounds like Pre-Code to me. Here's the rest of it from tcm.com.

Thursday, July 2, 2009

THE Public Enemy

He "ain't so tough."

Cagney sells himself a little short here, don't you think?

(uploaded by yoss71)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)