This is some setup for a pretty bad movie. Boss Nigger betrays its low budget and quickie schedule in almost every frame. Jack Arnold's triumphs as a director were two decades in the past, and the former sci-fi specialist at Universal brings little pictorial imagination to Williamson's story, or else he and Williamson, as co-producers, lacked the resources to bring either man's imagination to life. Much of the action plays out in poorly staged long takes, leaving the picture with little of the epic (or mock-epic) sweep the producers presumably aspired to. There's a particularly bad comic bit in which D'Urville Martin, as Williamson's sidekick, is trying to reach through a window and club a guard in a rocking chair with his pistol. Martin's reach is too short and he keeps missing. There's the beginning of a sight gag here, but they payoff would be to somehow get the guard rocking further and further back until Martin can whack him -- the gag is the rocking of the chair. Instead, Arnold has a captive woman in the room pretend to seduce the guard and simply shove the chair toward the window so Martin can strike home. That's typical of the inept comedy of the picture. Arnold had presumably proven himself as a comedy director by handling Peter Sellers in The Mouse That Roared, but here his touch is leaden. Fred Williamson is no Peter Sellers, of course, but bear in mind that Fred was after even bigger comic game.

Some of the ads for Boss Nigger wishfully label it "Another Blazing Saddles." It's tempting to dismiss the Williamson/Arnold picture as a ripoff of Blazing Saddles and to note that, in challenging Mel Brooks and Richard Pryor on the field of comedy, Fred and Jack were bringing a knife to a nuclear war. The facts suggest something more like coincidence. Boss Nigger was being mentioned as Williamson's next project as early as the spring of 1973, after the actor had made two successful "Nigger Charley" movies. Blazing Saddles wasn't released until February 1974, but Boss Nigger didn't make it into theaters until a year after that. The point of similarity, of course, is that in both films a black man becomes the sheriff of an Old West town. It wouldn't surprise me if Williamson had seen some version of a Blazing Saddles script, or if he had been offered the role that went to Cleavon Little after Warner Bros. wouldn't let Brooks cast Pryor. Whether he did or not, the one thing Williamson's own script for Boss Nigger has going for it is its discovery of a conceptual space not covered by Brooks, Pryor et al yet ideally suited for blaxploitation. In Blazing Saddles the black sheriff is a dupe, a pawn in Hedley Lamarr's plot to destroy the town of Rock Ridge, imposed on the town by Lamarr and his pal the governor. In Boss Nigger, Boss the bounty hunter (Williamson) takes over the town of San Miguel on his own initiative and for his own purpose. Boss wants the town and its jail as a base of operations from which to wage war on the gang of Jed Clayton (William Smith), with no nobler ultimate purpose, at first, than to collect the big bounty on Clayton's head. Much more so than in Blazing Saddles, the black sheriff in Boss Nigger becomes a lord of misrule. A lot of the labored comedy in the middle section comes from Boss and his sidekick Amos enforcing their "Black Laws," empowering themselves to fine or jail anyone who disrespects them by using the N-word or by any other means. Williamson and Arnold never really manage to make this funny, but the idea isn't bad.

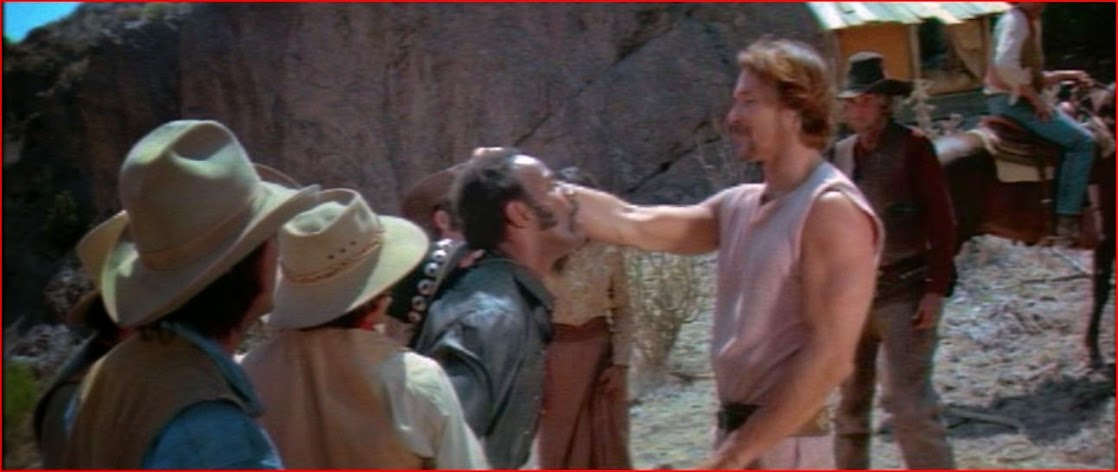

Comedy may not come naturally to Fred Willamson, and at times Boss Nigger becomes quite uncomic. Williamson gives Boss a social conscience by having him befriend the Mexican peons who live in impoverished segregation at the edge of town. He plays Moses by confiscating goods from the general store and distributing them to the peons. He and Arnold play mawkishly for pathos by having one boy befriended by Boss trampled to death by the horses of Clayton's gang after tumbling to the ground in slow motion. Later, Boss's girlfriend, the town's only other black person, is shot dead by Clayton, and there's nothing comic about Boss's vengeance. Clayton had given Boss his own beatdown earlier, and there's nothing comic about William Smith's villainy. Williamson and Arnold cast well for a big, mean bully, and Smith is one of the few performers to fully deliver the goods here. At the very end, Boss Nigger achieves something like an epic poignancy after Boss kills Clayton, only to be gravely wounded by the town's conniving mayor (R. G. Armstrong). Convinced (against Amos's assurances) that his wounds are mortal, Boss becomes desperate to leave San Miguel. He doesn't want to die in a white man's town, and he spurns the appeal of the white schoolmarm who befriended him (Barbara Leigh) to go with him. His few white friends, including the doctor and the blacksmith, load him into a wagon for Amos to drive away. On their way, they pass through the Mexican quarter, and the body of Boss's girl is loaded into the wagon. There's something of Shane in this ending, with the hero departing not dead but most likely dying -- despite Fred Willamson's admonition that he should never die (and should get the girl) in his own pictures. Of course the blaxploitation music that's played throughout the picture kind of kills the mood, but Williamson may not have thought the final pathos inconsistent with the overall burlesque. The ending hints at a deeper ambition than Williamson, who had not yet begun directing himself, wasn't ready to realize, and Arnold could no longer fulfill. Williamson would write a darker-toned western, Joshua, a few years after, and around the same time directed his own ill-fated collaboration with Richard Pryor, Adios Amigo. In sheer quantitative terms, Williamson was one of the major western stars of the Seventies, but Boss Nigger falls short for many reasons of any ambition he had to make a major western. In some ways, the even more impoverished Joshua is a better movie. But Boss Nigger will always be a point of interest for western and blaxploitation fans, and anyone attracted by the allure of the forbidden.

No comments:

Post a Comment