Michael Mann's Public Enemies, the latest cinema version of the hunt for John Dillinger, opens this week. That makes this as good a time as any to revisit a past favorite account of the same story, John Milius's directorial debut from 1973 with the great Warren Oates as the title bandit and Ben Johnson as Melvin Purvis as a Gorch-vs-Gorch showdown across the American midwest. I don't do this to set the Milius up as a standard for Mann to match. Dillinger's story is eminently available for anyone to make a movie from, and it had been done long before Milius, back in 1945 with Laurence Tierney starring. Many different takes on the Dillinger or Purvis stories are possible, but it's inevitable when I go to Public Enemies this weekend that I'll be comparing it to the 1973 film.

Michael Mann's Public Enemies, the latest cinema version of the hunt for John Dillinger, opens this week. That makes this as good a time as any to revisit a past favorite account of the same story, John Milius's directorial debut from 1973 with the great Warren Oates as the title bandit and Ben Johnson as Melvin Purvis as a Gorch-vs-Gorch showdown across the American midwest. I don't do this to set the Milius up as a standard for Mann to match. Dillinger's story is eminently available for anyone to make a movie from, and it had been done long before Milius, back in 1945 with Laurence Tierney starring. Many different takes on the Dillinger or Purvis stories are possible, but it's inevitable when I go to Public Enemies this weekend that I'll be comparing it to the 1973 film.Dillinger is a product of its own time as much as it is of Dillinger's own. It's part of a cycle of films about country bandits of the Depression years that dates back at least as far as Bonnie and Clyde and probably can be traced all the way to the Untouchables TV show. As part of that cycle, a key ingredient of the film is extreme violence. I think it's safe to say that more characters die in this movie by a wide margin than were killed during the actual Dillinger crime wave. This is violence for its own sake, killing for the love of killing, not to mention the love of squibs and blood packs and stuntmen falling off rooftops and landing on cars. There's a gratuitous visual focus on the moments of impact that probably won't be seen in Public Enemies, but some of the set piece battles staged by Milius could well look like a challenge to the director of Heat.

The country bandit films have a kind of master premise that crime was the only way some poor people were ever going to realize their particular American dreams. Dillinger embraces that idea, with emphasis on fame as the real goal for both Dillinger and his publicity-hungry pursuer. As one wannabe gang member says, "I'm already a murderer, so I might as well be famous." In one scene, Dillinger forces bar patrons to cough up their money, only to throw it all down on the floor once he's satisfied that they know who he is ("Look at my face, you sons of bitches!"). In his opening scene, he makes the fame-matters-more-than-money argument to a bank teller at gunpoint.

These few dollars you lose here today, they'll buy you stories to tell your children and your great-grandchildren. This could be one of the big moments of your life. Don't make it your last.

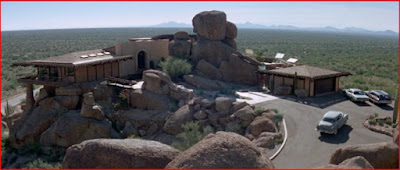

For Dillinger, fame is to be enjoyed while alive. When one of his partners is killed, he buries him in an unmarked grave with a twenty-dollar bill in place of a cross. He calls his pal a "well-known man" and compares him with the legendary outlaws of the Wild West, but he buries the man anonymously in order to save the corpse from exploitation by people who might dig it up and put it on exhibit. Fame is double-edged, however. Hiding out in Arizona under an assumed name, he finds that people tell him, "You look like John Dillinger." Photographs and newsreels make his face perhaps even more famous than his name. During a prison break, he accosts a mechanic who gapes at the sight of him. "I've seen your picture in the newspapers!" the mechanic exclaims, "You're him!"

Fame matters to the lawmen, too. The officer who first captures Dillinger makes sure to identify himself as Big Jim Willard, the killer of 35 men. Purvis is desperate to be recognized as a hero and envious of his boss J. Edgar Hoover stealing the spotlight. He's offended that children would rather play crook than G-Man and see no point in going to school since Dillinger didn't. But Purvis earns a good name at least among his enemies. When he takes down Pretty Boy Floyd, for instance, Floyd says, "You must be Purvis...I'm glad it was you." On both sides, it seems, a concern for reputation extends to having worthy opponents. Purvis himself says of Dillinger, "I've grown rather fond of him myself in a strange sort of way." Historically, Purvis never got the degree of fame he considered his due; the movie reminds us that he committed suicide in 1961 (Wikipedia says 1960) after breaking with Hoover and failing as a private detective.

To an extent, however, Milius loses track of the fame theme as the violence escalates, climaxing in his exaggerated version of the Little Bohemia raid. The film sort of sputters to a stop after that, as Cloris Leachman appears for little more than a one-scene cameo to set up the ambush outside the Biograph theater. While Milius has been exaggerating if not falsifying events throughout the picture up to this point, he fails to dramatize Dillinger's last days in any way. The statement that Dillinger likes to go to the movies is maybe meant to remind us that the man is sort of starstruck, but this is told of him rather than expressed by him. It seems like there should have been a final scene to give Oates a chance to sum up his and Milius's interpretation of the doomed criminal, but it either didn't happen or it ended up on the cutting-room floor.

A perfunctory finish and a bit of overindulgence in montages that mix black-and-white stills of the cast with newsreel and old movie footage are flaws, but overall Milius's Dillinger is a dynamic action film that is also a kind of American idyll in Fordian scenes that reunite Dillinger with his family and show a camaraderie among criminals that extends (perhaps improbably) across racial lines. The exception to this spirit is Richard Dreyfuss's surly hothead, Baby Face Nelson, a big man when threatening nuns but easily put in his place with a good bitch-slapping at the hands of Oates, one of cinema's master bitch-slappers in perhaps all senses of the term.

A glory of Seventies cinema is the fact that such a man as Oates could become a top-billed star of such mighty works as this one, Cockfighter, and Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia. There's an uncanny quality to the man that I can't quite call charisma. It's more like a sense that here is a man, perhaps the last real man or the last of a certain kind that was once more common hereabouts. It comes through even when he plays a cocky narcissist like Dillinger. It's a telling difference between then and now that Johnny Depp is the Dillinger of our time -- no offense intended to Depp, but you see what I mean. It's the same difference between Ben Johnson and Christian Bale, again with no offense to Bale, who I believe is actually closer to Purvis's real age at the time of the story. I look forward to Public Enemies and expect good things from it, but these are differences that mean something, if not to the particular film than to the movie industry as a whole.

This guard's skeptical declaration, "That ain't real!" when confronted with Dillinger's soap gun has long been my private mantra whenever I see an unconvincing special effect in a movie.

When I was a kid in the 1970s, it seemed like the past was just around the corner. I could go into used book stores and antique stores and buy old issues of Life, Look, the Saturday Evening Post, National Geographic, etc., for pittances by today's standards. There were parts of town that seemed to have hardly changed from twenty, thirty, forty years earlier. When I look at the location work in Milius's Dillinger and the open country roads I feel like I'm transported not directly to 1934 but to my own childhood, when it seemed that I could reach the Thirties on foot if I only knew the right route. If this be nostalgia, make the most of it. I don't expect the same sensation from Public Enemies, but if it achieves that on top of what I do expect, it'd be icing on a cake.

Here's the trailer, uploaded to YouTube by tvsdavid316

And as a bonus, old time newsreel footage of the real man in life and death, narrated by Lowell Thomas, who calls our culprit "Dilling-grr." It was uploaded by mrpitv