We often hear about "fate" or "doom" in discussions of film noir, but we hardly ever hear about "providence," and that, if nothing else, makes Roy Del Ruth's Red Light an exceptional noir. Its moral is "vengeance is mine, saith the Lord," and the screenplay by George Callahan and Charles Grayson, adapting a story by onetime cowboy star Donald "Red" Barry, goes about demonstrating the point with the dramatic logic of a golden age comic book. It starts off as menacing as you could ask for, with elite noir baddies Raymond Burr and Harry Morgan unhappily watching a newsreel from a prison projection booth. The news is that a heroic military chaplain (Arthur Franz) has just come home from the war to reunite with his doting older brother, trucking company boss Johnny Torno (George Raft). Burr's character used to work for Torno before he got caught embezzling. He feels entitled to revenge and the newsreel gives him an idea for the perfect revenge. Morgan's character is getting out shortly for good behavior (Morgan says this with as contemptuous a sneer as the words ever got). Willing to do anything for money, for Burr still has his embezzled money stashed someplace, Morgan becomes Burr's perfect weapon. Burr's blasphemous idea is to take revenge on Torno by killing his reverend brother. He doesn't anticipate that Morgan will do something stupid like telling the doomed priest that he's brought him something from Nick -- Burr's character if not Old Nick himself -- before shooting him in a hotel room.

We often hear about "fate" or "doom" in discussions of film noir, but we hardly ever hear about "providence," and that, if nothing else, makes Roy Del Ruth's Red Light an exceptional noir. Its moral is "vengeance is mine, saith the Lord," and the screenplay by George Callahan and Charles Grayson, adapting a story by onetime cowboy star Donald "Red" Barry, goes about demonstrating the point with the dramatic logic of a golden age comic book. It starts off as menacing as you could ask for, with elite noir baddies Raymond Burr and Harry Morgan unhappily watching a newsreel from a prison projection booth. The news is that a heroic military chaplain (Arthur Franz) has just come home from the war to reunite with his doting older brother, trucking company boss Johnny Torno (George Raft). Burr's character used to work for Torno before he got caught embezzling. He feels entitled to revenge and the newsreel gives him an idea for the perfect revenge. Morgan's character is getting out shortly for good behavior (Morgan says this with as contemptuous a sneer as the words ever got). Willing to do anything for money, for Burr still has his embezzled money stashed someplace, Morgan becomes Burr's perfect weapon. Burr's blasphemous idea is to take revenge on Torno by killing his reverend brother. He doesn't anticipate that Morgan will do something stupid like telling the doomed priest that he's brought him something from Nick -- Burr's character if not Old Nick himself -- before shooting him in a hotel room.Torno arrives in time to hear his brother's dying words: "the book." Johnny assumes that the priest means the ornate Bible he gave to his brother years ago. Hoping to find some clue to the killing, he pores through the holy book in search of accusatory marginalia and finds nothing. Some time later, it occurs to him that his brother may have meant the Gideon Bible bound to be found in any hotel room. He returns to the death room and finds that book missing, increasing his suspicion that it contains crucial information. By now several other people have occupied the room; one of them must have taken the book. If so, why? Johnny sets out to track down each of the intervening guests, while Nick, now released in his own right, lurks about recklessly, begging Johnny for another chance. The first one Torno finds is showgirl Carla North (Virginia Mayo), whom he recruits as an assistant once convinced of her innocence. Concerned that Torno may be on to something, Rocky (Morgan) stalks our hero and finally has it out with him in another hotel room. Coming out slightly the worse for wear, Rocky decides his best option is to blackmail Nick and cash out, letting him know that he spoke his name to the priest and guessing that the priest wrote it in the book. Nick responds like a Raymond Burr noir villain should and tosses Rocky from the caboose of a speeding train.

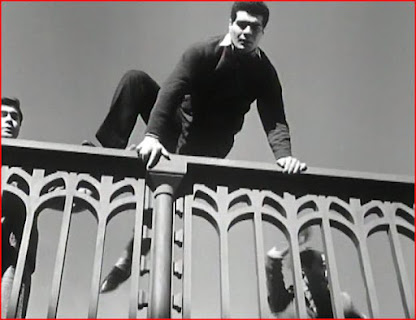

Further complications take us to the belated discovery of the genuine Gideon. As a worried Nick watches with others concerned in the case, Torno desperately thumbs through the tome until he finds a handwritten warning, his brother's last message, against seeking revenge. Assured that the priest named no names, Nick attempts an inconspicuous exit, but whom should he find at the bottom of the stairs but battered and bloody Rocky, ready for a little revenge of his own. Nick gets the better of an impromptu shootout, but Rocky, not quite the forgiving sort, lives long enough to denounce his former pal for his own death and the priest's. This sets up a classic set-piece showdown as Torno chases Nick to the roof of his building, where an electric sign advertises his business. Cinematographer Bert Glennon makes the most of the opportunity to play light against darkness as Burr darts between the big glowing letters, looking for the perfect shot at Raft, until an exposed wire becomes his undoing. Once Nick is properly fried and justice is served, the camera pulls back to make sure you see Johnny Torno's ad slogan, "24 Hour Service." This is what Torno had demanded of God in a moment of sacrilegious impatience when he'd been urged to let God do His thing in His own time. Johhny Torno is film noir's Job, driven to curse God for his affliction yet rewarded, on the assumption that he's bowed to his brother's wisdom, with instant justice. Whether he gets the girl, too, hardly matters since there's zilch chemistry between the monomaniacal (or is it just plain monotonous) Raft and the thanklessly-tasked Mayo. What makes Red Light worth seeing is the direction, the cinematography, and above all Raymond Burr, king of noir villains, in fine, foul form. It cannot be stressed enough to those who know Burr only as Perry Mason, old or young, or as that guy in those Godzilla movies, that film noir Burr is a beast who was best when he was bad. He's dependably evil here and ably assisted by Morgan, who for noir purposes was either sinister, stupid, or both. Their vital villainy and the screenplay's eccentric spirituality make Red Light idiosyncratic enough to earn a look from any noir fan.

A

A

J

J

H

H