It would be going too far to call Edgar Selwyn's adaptation of a Broadway play as a buried treasure, but it's definitely a relic in any sense of the word. The sense I choose is "invaluable yet forgotten piece of pop culture history." You would think that a movie with a special-effects sequence of an aerial bombing of New York City might be better remembered today, at least among genre film fans. Let me restate the argument: you would think that a film in which the Empire State Building and the Brooklyn Bridge are blown up, released within months of King Kong, might occupy at least a footnote in film history. But I can't recall reading or hearing about Men Must Fight until TCM scheduled it for early Monday morning and I read the cable guide entry about New York being bombed in 1940. I say again: you would think, yet ...

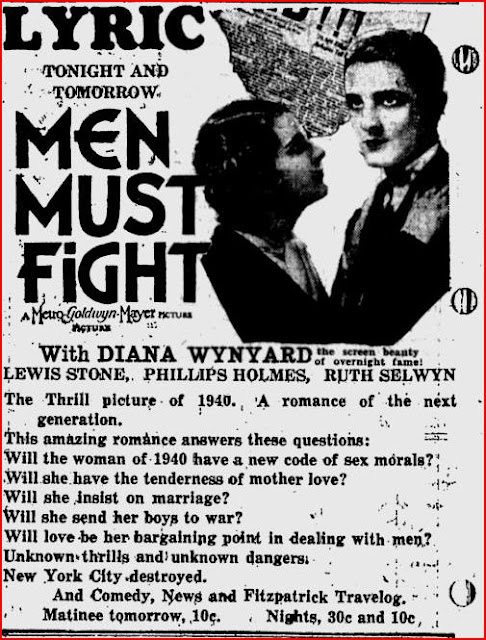

It would be going too far to call Edgar Selwyn's adaptation of a Broadway play as a buried treasure, but it's definitely a relic in any sense of the word. The sense I choose is "invaluable yet forgotten piece of pop culture history." You would think that a movie with a special-effects sequence of an aerial bombing of New York City might be better remembered today, at least among genre film fans. Let me restate the argument: you would think that a film in which the Empire State Building and the Brooklyn Bridge are blown up, released within months of King Kong, might occupy at least a footnote in film history. But I can't recall reading or hearing about Men Must Fight until TCM scheduled it for early Monday morning and I read the cable guide entry about New York being bombed in 1940. I say again: you would think, yet ...The problem with Men Must Fight is that it takes a slow-burn approach to its subject within the framework of a drawing-room melodrama about a husband, a wife and a son. It starts in 1918 with an American flier (Robert Young) and his nurse girlfriend (Diana Wynyard) on the Western Front. There's another man, older and an officer, Ned Seward (Lewis Stone), but he knows when he's beat. But there's hope yet for him, for few characters in films have been so obviously doomed as Young's airman. When Laura, the nurse, pins her four-leaf clover on his uniform before a mission, it may as well be a nail through the lid of his coffin. As it turns out, he survives the crash but dies not long afterward. He's left something of himself behind, however, and for that reason Laura is reluctant to return to America when the war ends. That's when Seward, scion of an aristocratic line, chivalrously steps in to make an honest woman of Laura.

Twenty-two years later, Ned Seward is Secretary of State and Laura Seward is one of the country's leading peace advocates. They've worked in tandem, Ned having negotiated a major peace treaty with Eurasia, the other great power of 1940, and their son Bob (Phillips Holmes) has an irreverent attitude toward old-school patriotism that gets him in trouble with his girlfriend Peggy (Ruth Selwyn) and her mother. Bob had the gall to criticize a crowd that nearly lynched a "Bolshevik" who'd desecrated an American flag. It's a minor incident, but suddenly things don't seem quite so peaceful. And not long after, Ned takes a phone call from Washington and has to take a quick flight there. Things are falling apart fast after the assassination of the American ambassador to Eurasia -- it's an insult the nation will not tolerate. A show of force must be made for the sake of national honor. Ned insists on this, but Laura sticks to her pacifist guns. She organizes a peace rally that's televised across the country -- remember, this is 1940 -- in which she delivers a Lysistrata ultimatum, threatening a global birth strike if men won't renounce war. Her speech enrages a group of pool-playing louts watching at a nearby bar. They storm the coliseum where she's speaking, but a Secret Service detail gets her out safely. A crowd gathers outside the Seward home, but Ned calms them with his assurance that his own son will serve and sacrifice if war makes it necessary. But he didn't consult Bob before saying that, and Bob's having none of it. A nonviolent war of wills breaks out that climaxes with Ned's revelation that Bob is no Seward and, on top of that, unworthy of the honorable name. There's an extra edge to the three-way family conflict that emerges when Ned accuses Laura of raising Bob to hate war mainly because Bob's all she has left of her true love. Looked at from another angle, it's almost as if Ned is pushing for war in order to eliminate the symbol of his secret inadequacy as a lover. It's melodramatic in a hokey way, but it's also a little chilling.

And the war came. From all reports, our boys are getting their asses kicked by the Eurasians, who appear capable of projecting force across the Atlantic to take the Panama Canal and, need I add, bomb New York City. The bombing scene only lasts a couple of minutes, and the M-G-M special effects team isn't quite of RKO caliber, but the audacity of the vision, as giant facades come crashing down to street level, still impresses. Despite the high-profile hits, the city isn't really that much worse for wear, from appearances, and Laura Seward and Peggy manage to escape even though their car is caught in the middle of the bombing. Still, Laura's injuries are enough to turn the tide for Bob. Against her wishes, he enlists. Against Ned's wishes, he doesn't join the chemical corps, as he'd wanted, but the air corps, where he'll be on the front line of fighting. From what Ned has told us about whole air fleets being wiped out by poison-gas projectiles, Bob has probably doomed himself. He hasn't exactly come to love war, either. It's still a "dirty, stupid business" to him, but he explains the title of the play (which M-G-M considered changing to What Women Give Up) by saying, more or less, that a man's gotta do what a man's gotta do. The film closes with an impressive shot of a massive American formation flying over the city as three generations of women -- Peggy, Laura and Ned's mother (May Robson) watch with disgust from a balcony. The old lady has grown more convinced that women ought to rule the world, and Peggy now takes Laura's side, vowing never to let any son she has by Bob go to war, but all three seem resigned to things changing very little in the future.

The relatively sedate build-up to mayhem -- including a steamship scene with cameo by drunken master Arthur Housman -- who claims that Europeans don't appreciate alcohol because they never had to do without it like Americans had, has probably hurt the reputation of Men Must Fight more than anything else. For an impatient viewer, the first 40 minutes or so, at least until the riot at the Coliseum, will be like sitting through the romantic scenes in Marx Brothers films. It doesn't help that the film lacks especially charismatic actors, though Stone makes the most of his bleakly authoritarian Pre-Code persona. But these faults don't explain why Men Must Fight doesn't endure with genre fans for whom the bombing sequence should stand as some sort of cinematic milestone. I see two likely reasons for its neglect. First, while it can be called a science-fiction film for predicting the near future, it doesn't project far enough to remain relevant, compared to H. G. Wells's Things to Come, which resembles Men Must Fight for its first reel but then keeps pushing decades ahead. Second, and maybe more importantly, Men Must Fight envisions a future war but isn't really an anti-war movie. It isn't a pro-war movie, either. Its tone is ambivalent; its title is declarative rather than imperative; its attitude toward war is resignation rather than denunciation. The playwrights and adapters seem honestly to have aimed for balance, for letting both sides have their say and making their best arguments. It can't help but appear to equivocate on the crucial question of the age, and however honest or objective its equivocation, it can't help but damn the film for many viewers. But it's still a cinematic milestone, as far as I can tell, and an interesting study of attitudes toward war when the buildup to the real Second World War, which arrived a year ahead of schedule, had only just begun.

No comments:

Post a Comment