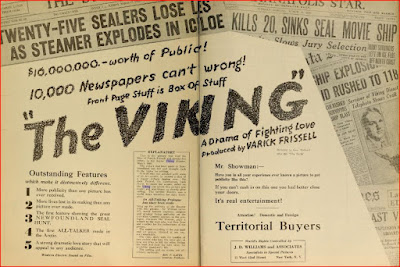

The French have a term, "film maudit," for "cursed" films, by which they and film buffs everywhere mean those movies that suffer from difficult productions and/or box office rejection. By some standards, Andrew Stanton's John Carter qualifies as a film maudit because of the critical drubbing it's received and the abysmal losses it now represents for the Disney company. However, if we were to consider George Melford's The Viking a film maudit, few other films would merit the label. This early Canadian talkie may be the ultimate film maudit, not just for the horrific circumstances that ended the production, but for the way the film itself seems in retrospect to court doom. It was released in the summer of 1931, its title changed from "White Thunder" in an act of ghoulish exploitation. The Viking was the name of the vessel, a real working ship, that took cast and crew to the Labrador ice fields to film the seal hunts on the ice. After a preview of "White Thunder" played poorly, producer Varick Frissell ventured back to Labrador (without Melford, as far as I know) to shoot more actuality action scenes. On that trip, the explosives kept in store for ice breaking blew up on board, killing Frissell, his cinematographer and two dozen others. The story is told in a preface to the picture proper, following a title card that fairly identifies the event as the greatest catastrophe in the history of motion pictures. It so happens that The Viking is a film about a hero considered a jinx -- or "jinker" in the local slang -- who sails with the title vessel against the will of a captain who boasts that he's never lost a man on any expedition. That actor was the real captain of the Viking during the initial filming. He didn't sail on the fatal return trip, but his mate did, and died.

The French have a term, "film maudit," for "cursed" films, by which they and film buffs everywhere mean those movies that suffer from difficult productions and/or box office rejection. By some standards, Andrew Stanton's John Carter qualifies as a film maudit because of the critical drubbing it's received and the abysmal losses it now represents for the Disney company. However, if we were to consider George Melford's The Viking a film maudit, few other films would merit the label. This early Canadian talkie may be the ultimate film maudit, not just for the horrific circumstances that ended the production, but for the way the film itself seems in retrospect to court doom. It was released in the summer of 1931, its title changed from "White Thunder" in an act of ghoulish exploitation. The Viking was the name of the vessel, a real working ship, that took cast and crew to the Labrador ice fields to film the seal hunts on the ice. After a preview of "White Thunder" played poorly, producer Varick Frissell ventured back to Labrador (without Melford, as far as I know) to shoot more actuality action scenes. On that trip, the explosives kept in store for ice breaking blew up on board, killing Frissell, his cinematographer and two dozen others. The story is told in a preface to the picture proper, following a title card that fairly identifies the event as the greatest catastrophe in the history of motion pictures. It so happens that The Viking is a film about a hero considered a jinx -- or "jinker" in the local slang -- who sails with the title vessel against the will of a captain who boasts that he's never lost a man on any expedition. That actor was the real captain of the Viking during the initial filming. He didn't sail on the fatal return trip, but his mate did, and died.This awful backstory makes Melford's film even more breathtaking than it would have been otherwise. It's the last of three extraordinary films that I know of in the director's filmography, the others being that seminal romantic abduction fantasy The Shiek, and Universal's Spanish-language version of Dracula, which like The Viking was considered a lost film for many years before rediscovery. Like the "Spanish Dracula," The Viking leaves you wondering what Melford contributed to the visuals. Was he or Frissell the auteur of the piece? Whose eye -- or should doomed cinematographer Alexander Gustavus Penrod get the credi? -- captured the awesome images -- probably still irreproducible even with today's CGI -- of the vast rippling, pitching icescapes of the seal hunts, a white world in perpetual tumult, a rollercoaster on a continental scale? Who could not record pictorial wonders in such a setting? You have to wonder because the dramatic scenes before and after the expedition are nothing special, and those are the parts most certainly directed by Melford. Nor is the script by Garnett Weston that special. At its core it echoes The Four Feathers. A despised young man (future Durango Kid Charles Starrett), condemned for weakness if not cowardice and stigmatized as a jinker, proves himself by rescuing a sometimes-hostile acquaintance who's temporarily blinded. This human story is really a sideshow or subplot compared to the amazing actuality footage, which includes a seal hunt that offers a sop to animal lovers. We're supposed to identify with the hunters and their dangerous quest for wealth, but once they catch up with the seal herd and the shots start firing, Melford (or Frissell) cuts to a baby seal bleating helplessly by itself, too young or too frightened to know what to do to save itself. An older seal -- the baby's parent or just a conscientious seal citizen? -- lurches back onto the ice to steer and shove the baby to the shelter of the water. As the shots keep ringing out, the scene fades out on the baby's face peeking through the surface, presumably safe but plainly terrified. The individual's survival obscures the collective massacre, but I can imagine some selectively sensitive people feeling that Frissell and company got what they deserved later.

Varick Frissell was a disciple of Robert Flaherty, the pioneer documentarian and arguable forefather of "reality TV" who combined actuality with dramatization. The Viking's semidocumentary nature strikes me as preminiscent of today's "dangerous job" programs like Deadliest Catch, some of which have lost cast members in real-life accidents. Somehow I find The Viking's foregrounding of acknowledged fiction more honest than the modern pretense of many "unscripted" programs. Back in 1931, I think everyone understood that the story was the necessary excuse for the good footage that actually dominates the film and makes it memorable today. Whoever shot it or shaped it, that footage is so impressive that it'd impress people who have no clue of the fate of the ship and its crew. I'd like to think it'd impress people accustomed even to color and CGI and 3D today. The Viking proves that truth can still be more fantastic than fantasy.

If you missed the TCM broadcast of March 30, The Viking can be seen in its entirety on YouTube.

No comments:

Post a Comment