A randomly comprehensive survey of extraordinary movie experiences from the art house to the grindhouse, featuring the good, the bad, the ugly, but not the boring or the banal.

Wednesday, May 30, 2012

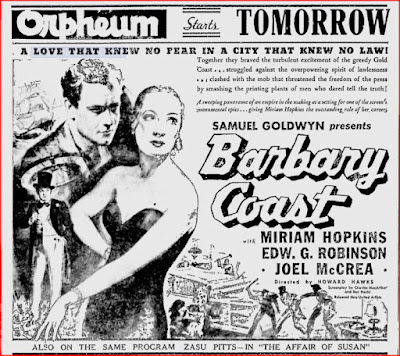

DVR Diary: BARBARY COAST (1935)

Freely adapted by the legendary team of Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur from one of Herbert Asbury's chronicles of urban lowlife -- the same author was the source for Martin Scorsese's Gangs of New York -- Howard Hawks's film for Samuel Goldwyn focuses on a fortune-hunting female (Miriam Hopkins) who arrives in 19th century San Francisco to learn that her betrothed to be has been killed by the local vice lord (Edward G. Robinson). With no other prospects in sight she attaches herself to Robinson and becomes a corrupt croupier at his casino. Robinson controls the town; the sheriff and judge are his pawns and advocates of law and order, led by Harry Carey, seem powerless to thwart him. They turn to a newly-arrived newspaperman but Robinson and apprentice thug Brian Donlevy intimidate the ink-stained wretch into effective silence, sparing his life only because Hopkins, who'd arrived with him, begs that he be spared, and Robinson feels he should do nice things for her every so often. But Robinson isn't getting everything out of the relationship with Hopkins that he'd hoped for, and he resents it passionately. If Hopkins is the center of the picture you can see the outline of an old Lon Chaney Sr. vehicle just below the surface. Robinson is playing a version of his standard gangster here, but the extra element he contributes is his character's apparently genuine longing for love. You feel it in his angry exchanges with Hopkins, when he demands the love she'd promised. Robinson brings a passion to these scenes above and beyond the usual cruel lust of the melodrama villain. But it's up to him to invest the scenes with emotion, since Howard Hawks isn't making a Chaneyesque movie. I don't mean that Hawks neglects the actor or leaves him to his own devices; he certainly deserves some of the credit for the intensity Robinson brings to his performance. But Hawks isn't really interested in the pathos an actual Chaney vehicle was designed to generate. Neither he nor Robinson plays for pity, nor do they dare suggest that the character's longings redeem him. Yet the film closes on a note of renunciation worthy of Chaney.

Hopkins finds true love with a handsome young prospector with a poetic temperament (Joel McCrea) whom Robinson has vowed to destroy. Again, Hopkins begs Robinson to spare a man, this time promising never to see McCrea again and to give Robinson the love he craves if only he'll let McCrea live. Robinson agrees and allows Hopkins to see McCrea off on a boat. Watching her make her farewell, Robinson recognizes true love and apparently realizes that he can't have it, at least from Hopkins. That leaves few other options for him, since Carey has finally incited the citizenry into vigilante action and his men are at work destroying Robinson's operations and lynching his men. Perhaps Robinson realizes that his time is running out and he simply has nothing left to offer Hopkins. Maybe he realizes that he can't have love because he can't love. So he does the next best thing, and probably the best thing he's capable of. He orders Hopkins to stay on the boat with McCrea and disembarks himself to face Carey's lynchers alone. To an extent the way he meets his end ennobles him, since he shows no fear, urging Carey to get on with whatever he intends. The matter-of-fact way in which the director films this, the avoidance of pathos, may be the most Hawksian thing about the picture. Otherwise it's a slick production that evokes the mythic grunge and glamor of Gold Rush San Francisco, primarily powered by Robinson despite Hopkins's top billing. If it's remembered now, it's most likely as a Robinson movie than as a Hopkins or Hawks show. Hopkins is fine in her role, as is McCrea and Walter Brennan in one of his first high-profile character turns. But Robinson gives the film what character it has as the embodiment of the city's storybook decadence, and he's what makes it worth watching today.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

3 comments:

Sam, According to Eddie in his autobiography, the animosity with Hopkins was very real, as was the film's famous slap. His book is very gentlemanly, but you can tell he didn't care for Hopkins at all, nor she him. Good write-up of a worthwhile film, I wish it was more widely available.

Hopkins probably realized Robinson was stealing the film from her, to some extent with Hawks's help, while poor McCrea isn't even in the running. This must have been one of his last pictures where he served primarily as beefcake before achieving stardom in his own right.

Samuel, I saw this a while back and remember enjoying the portrayal of a fog-ridden Barbary Coast but feeling the film wasn't very Hawksian - apparently he had a lot of interference from Goldwyn. I did like both Robinson and Hopkins' performances, but agree that McCrea doesn't get much of a look-in and his character, wandering through gangland with a poetry book, doesn't ring true. My memory is that the ending seemed a bit much and didn't go with Robinson's character up to that point, but your comments on this and comparison with Chaney have me thinking again.

Post a Comment