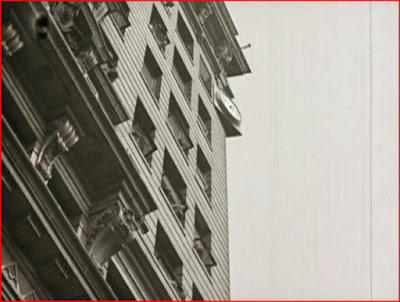

Despite two directors and Hal Roach looking over his shoulder, Safety Last! is Harold Lloyd's show and the film that made him, by then already a star, an immortal. Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton are deemed Lloyd's masters, but the definitive image of American silent comedy is still Lloyd dangling from that clock on that building. It's but a moment in an uncanny twenty-minute climb that preserves its power to thrill pretty much undiluted after 86 years.

Despite two directors and Hal Roach looking over his shoulder, Safety Last! is Harold Lloyd's show and the film that made him, by then already a star, an immortal. Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton are deemed Lloyd's masters, but the definitive image of American silent comedy is still Lloyd dangling from that clock on that building. It's but a moment in an uncanny twenty-minute climb that preserves its power to thrill pretty much undiluted after 86 years.The climb eclipses the majority of the film, which is so archetypal a Lloyd story of striving for success that, despite being identified only as "The Boy" in the opening credits, a pay stub identifies him as "Harold Lloyd." Harold has gone to the big city to make good, and sends bits of jewelry home to his sweetheart, "The Girl," (Mildred Davis, the eventual Mrs. Lloyd) as boasts of his success. In reality he is sacrificing food and falling behind on his rent in order to buy the trinkets with his salary as a flustered fabric salesman in a department store. Eventually The Girl comes to visit and Harold must pretend that he holds a higher position.

Humiliated in his own eyes despite surviving his imposture, Harold is more desperate than ever to achieve some coup, and the chance comes when management wants a publicity stunt to promote the store. Harold's roommate (Bill Strother) is a prodigy as a climber, as Harold had seen when they both had to get away from an angry cop. He proposes having his roommate climb the store building to attract a crowd. If it goes over, he'll earn a $1,000 bonus. But just before the climb begins, the angry cop recognizes Harold's roommate and chases him inside the building. With the pressure on and his pal unavailable, Harold must climb the tower himself, with the roommate coaching him from floor to floor but always telling him to go one floor more "until I ditch the cop."

There's the clock, and there's Harold Lloyd. I will not show him dangling from it.

The pure thrill of the climb is leavened with more mundane comedy bits as Harold is beset by pigeons, a rat, a net, a dog, a hectoring old lady and a man posing, gun in hand, for a crime magazine cover. And on every floor his friend reliably appears to excuse himself for failing to shake the cop. None of this is exactly hilarious, but it does build up anticipation for what godforsaken thing The Boy might encounter next. And Lloyd tops it off with a tension-straining bit of business on the roof with some spinning doom device which is either a wind gauge or something meant only to hit human flies in the head. He knows what has to happen and the audience knows it, so he makes them wait, teasing the blow several times over before taking it and setting up the final, supposedly spectacular but actually anticlimactic gag in which Lloyd's stuntman swings from his heel through space. Nothing can top the spectacle of the climb.While Bill Strother plays Harold's unreliable human-fly pal in the story, in real life he was the human fly who inspired the movie and did the heavy-duty climbing in long shots like the one below.

So Safety Last! isn't the funniest silent comedy by any means. Nor does it come close to Lloyd's funniest films, among which I count Why Worry?, For Heaven's Sake and his pioneer fish-out-of-water sound film The Cat's Paw. But the climb is not so much a gag as a "chariot race" climax on the Ben Hur model, the term Merriam C. Cooper used to describe another climb up a building in King Kong. For want of a really definitive term, Harold Lloyd's climb is one of the greatest things you'll ever see in a movie.

2 comments:

The climb, of course, is symbolic of the American desire to climb into a higher socio-economic class -- by no means easy, but not impossible, either; this was the Go-Go Twenties, after all. Lloyd climbs successfully, and he gets The Girl. I think this is why, along with the sheer grandeur you rightly refer to, that Safety Last! is so powerful and archetypal a film; that climb with all its physical impressiveness also really stands for something.

The climb is the obvious highlight of this film and the reason it is best known. It is great filmmaking and great acrobatics, which many of the masters of silent comedy all excelled in, that said, you're right the rest of the film is not classic, it is not bad, but Lloyd has done better as you say.

Excellent essay!

Post a Comment