Harry Langdon is generally considered the fourth of the great clowns of American silent film, behind Charles Chaplin, Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd. Langdon emerged the latest of the four, rose the fastest, and fell fastest. His career as a star of A features was finished before the actual end of the silent era, though he continued working in shorts and in occasional supporting roles in features until his death in 1944. His first film as his own director, Three's A Crowd, is known as the film with which he jumped the shark and lost his audience irrevocably, with two features left to make under his contract with First National Pictures. The last feature, Heart Trouble, is a lost film, signifying Langdon's ruin.

Harry Langdon is generally considered the fourth of the great clowns of American silent film, behind Charles Chaplin, Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd. Langdon emerged the latest of the four, rose the fastest, and fell fastest. His career as a star of A features was finished before the actual end of the silent era, though he continued working in shorts and in occasional supporting roles in features until his death in 1944. His first film as his own director, Three's A Crowd, is known as the film with which he jumped the shark and lost his audience irrevocably, with two features left to make under his contract with First National Pictures. The last feature, Heart Trouble, is a lost film, signifying Langdon's ruin.So what was I doing watching this doomed venture? I have a biographical interest in film, and I've been interested in Langdon since Walter Kerr wrote about his rise and fall in The Silent Clowns, one of the best books of movie criticism ever written. Kerr's account of Three's A Crowd was damning, though he also described it as a near-masterpiece. It made me curious to see whether it was really a career-killing movie. But I must also confess that the real hook for me was the commentary track. I don't listen to commentaries often, but the big exception for me is the work of David Kalat. Along with being an expert on Dr. Mabuse, Kalat is a big booster of silent comedy. He put out a terrific DVD collection of Langdon shorts a few years ago, every one of which had a commentary track, provided by him or fellow Langdon fans. He is a passionate advocate of Langdon as a still-misunderstood genius whose comic sensibility may actually be better appreciated by modern audiences than it was in the Twenties. He is also a revisionist who challenges Kerr's interpretation of Langdon's career as well as self-serving dismissals of the comedian by his collaborators, most notably Frank Capra. So I definitely wanted to hear what Kalat had to say about Three's A Crowd, while the film would determine whether Kalat was full of it or not.

Kalat is most determined to refute the idea that Langdon "jumped the shark" with Three's A Crowd. The question is: did Langdon do something wrong, screw up his gimmick and alienate the fans of his earlier films? That's what Kerr claimed; he wrote that Langdon abandoned an ambiguity about whether his character was a mature adult or not. Capra made a similar claim; he accused Langdon of abandoning a story formula wherein his infantile innocent got by on sheer good luck, if not God's grace. Kalat dismisses Capra as a liar and claims that Kerr misunderstood Langdon because he lacked access to the comedian's complete canon. Kalat's revision is twofold. He argues that contemporary critics and audiences did not perceive that Langdon had gone too far, misunderstood his appeal, or abandoned a successful formula. More significantly, he demands that the box office failure of Three's A Crowd be understood in the context of a general decline of popularity for slapstick comedy circa 1927. Keaton and Lloyd had box office disappointments (The General and The Kid Brother) that year, while Chaplin's The Circus failed to top The Gold Rush with moviegoers or critics. Langdon didn't recover from the failure of Three's A Crowd, Kalat suggests, because he was the least established of the major comedians, and thus the first to be dropped during a loss of interest in slapstick. But his box-office failure doesn't prove that Three's A Crowd was a wrong turn. What, then, does the film prove?

According to Kalat, Langdon's directorial debut is the culmination of his own theories of comedy and the ultimate statement of his comic persona. For Kalat, Langdon's is the comedy of futility and slowness bordering on stasis. The Langdon character is slow-witted and slow in motion; the slowness originally set him apart from his frenetic peers, and goes back to Langdon's days as a vaudeville star. There's a link between his stasis and his futility that found a fan in Samuel Beckett; Kalat says that, had Langdon lived, the playwright would have cast him instead of Keaton in Film. Three's A Crowd brings futility to the forefront after Capra had contrived happy endings for Langdon in earlier features. Capra characterized Langdon's ambition as an inappropriate insistence upon pathos in pretentious imitation of Chaplin. For Kerr, Langdon's presentation of himself as a man with normal heterosexual yearnings for family betrays the ambiguity of the boy-man persona that allegedly made Langdon a success and makes his ordeal in Three's A Crowd merely pathetic. Kalat claims that Langdon was ahead of his time in attempting to make comedy out of pessimism and unredeemed futility.

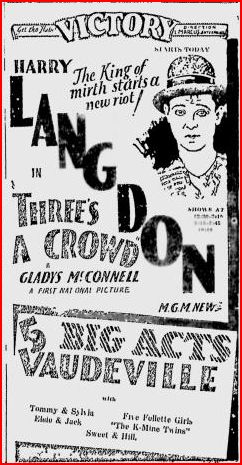

Let's start to clear things up a little. First of all, Three's A Crowd isn't an imitation of Chaplin, but a commentary if not a sardonic parody of the romantic Tramp. In simplest terms, the plot elaborates on themes Chaplin had played since The Tramp back in 1915. Langdon's film is the story of a hapless fellow, an assistant junkman who makes enough to keep his own apartment but is unfulfilled and lonely. He longs for a wife and child, adopting a doll briefly to toss in the air the way his boss tosses his own son. His wish comes true in miraculous fashion when he discovers a woman lying unconscious in a snowbank outside his apartment. He carries her up the long, slanted flight of stairs to his home and calls a doctor. In a development the original advertising kept discreetly secret, the woman is pregnant and about to give birth. She has fled an abusive husband and found a refuge with Harry.Deceptive advertising for Three's A Crowd. This piece would make you think that Harry Langdon's in the middle of a romantic triangle. See below for the truth.

Never was a fight more fixed than this.

With Chaplin, Kalat claims, this moment always comes with a conscious gesture of renunciation, as if Chaplin knows he could keep the girl with his charm but also that he, a tramp, can't provide for her as she deserves. In Three's A Crowd, Langdon is pretty much a bystander to the destruction of his dream. He can't pretend that it's up to him to let the girl go or not. He can only acquiesce, but then what?

Walter Kerr describes Three's A Crowd as framed by a brilliant visual gag. It opens at dawn, when the streetlights go out. At the end, Kerr recalled, Harry lurches out into the street after the reunited couple and child, candle in hand. As dawn arrives, Harry blows out his candle at the exact moment that the lights go out. Kerr describes Harry panicking, thinking that he blew out the streetlights, and exiting to end the film. The critic misremembered the ending. Harry doesn't react at all to the lights going out, because he has another agenda that takes him to the actual final scene of the film. He returns to the palmist's shop, where the fortune teller had made a false prediction to him. By this point in a Chaplin film, the Tramp has resigned himself to solitude and resolved to carry on cheerfully. Under similar circumstances, Keaton or Lloyd might attempt comic suicide. Now Langdon charts his own course: Harry will curse his fate by throwing a brick through the palmist's window. Except that he can't bring himself to break the window or the law. He tosses the brick out of harm's way, only to set an oil drum rolling loose from a wagon and through the palmist's window. Now Harry runs, and now the film ends.

That actually is a brilliant ending and a powerful statement on some level by Langdon. But if there's a problem with Three's A Crowd, it may be that Langdon could have told his basic story nearly as well with a two-reeler. It's not that he takes too long with his slowness. The opening scenes of his reluctant waking for work are properly paced, and he milks his deliberation to the maximum when Harry discovers the girl in the snow. He eyes her for a long still moment, crouches to examine her more closely. He stands erect, spreads his arms and makes a few feeble gestures appealing for aid. He crouches again to examine her some more, then gets up again. He repeats the cycle once more before finally picking her up. You're supposed to be saying, "Help her, moron!" while understanding or even empathizing with his stunned reticence. Watching sequences like that I see what Kalat appreciates about Langdon. There's a lot to appreciate visually about the film as well. Langdon's production team built him a picturesque wintry cityscape that reflects the star's own longstanding concern with scenic effects dating back to the stage. The cinematography is top notch, both during the snowstorm scenes and a stormy night that sets up Harry's dream sequence.

There's at least one great physical gag involving a trapdoor in Harry's apartment and his carpet. Harry falls through the trapdoor and takes some of the carpet with him. The carpet eventually jams the trapdoor, leaving Harry suspended over an alleyway. He can barely manage to climb up the carpet, but when he pushes the trapdoor open to get inside, he only starts the carpet and himself falling again. Again, he repeats the sequence several times before he lands on the roof of a truck. This strikes me as his mockery of thrill comedy on the Lloyd model. Lloyd or Keaton would probably have swung their way to safety, and Chaplin might have managed to surge through the trapdoor fast enough to make it safely home. Langdon, however, is truly hopeless. If there's suspense here, it's all about waiting for him to fail and knowing he will.Slightly expressionist exteriors and chiaroscuro interiors photographed by Elgin Lessley and Frank Evans.

Even at 62 minutes, however, Three's A Crowd drags. There's an interminable pie-making sequence that nearly stops the film dead without being funny. The mother remains invalided throughout the picture, leaving little opportunity for real interaction between her and Harry. He spends most of his time simply watching them, as if knowing it's borrowed time. The dream is cut awkwardly to deny us the usual payoff. We see Harry knocked out, but we don't see the husband hit him. Call it dream logic, I suppose, but the film sometimes seems perversely dedicated to denying the audience any satisfaction. Capra might say this was because Langdon really wanted to make us cry. I think not, but his bleak approach to comedy here, which I think Kalat describes fairly accurately, was bound to alienate audiences then and would probably alienate nearly as many people now. Thanks in part to Kalat I "get" Three's A Crowd and appreciate what Langdon was attempting, but it still isn't a great comedy. Watching it with the commentary was a fascinating experience, reminiscent of those old Robert Youngson documentaries Kalat himself cites -- Youngson described Three's A Crowd as Langdon reaching for a "celestial high note," -- and maybe the film should be presented the same way, with the commentary in the forefront, so that fiction becomes documentary.

Kino released Three's A Crowd as part of its Slapstick Symposium series, the title never being more appropriate, and included Langdon's follow-up feature, The Chaser, without commentary from Kalat. Chaser is Langdon's comic nightmare of emasculation as Harry, wrongly convicted of disorderly conduct at home, is "denied the privileges of manhood" by an experimental judge. He's compelled to do housework and wear an apron that somehow makes him look attractively feminine in the male gaze of visitors. Walter Kerr misinterpreted this film, too, describing a scene in which Harry surrenders a baby's crib to the repo man as a confession of impotence when emasculation is clearly the problem; he doesn't turn the thing over, nor a potty-training chair, until he calls the wife first. It works as a comic nightmare until a botched suicide attempt halfway through the picture, but then veers off into some generic golf humor and a strange sequence portraying Harry as a kissing bandit before a lame payoff with his wife mistaking him for a ghost. It's still worth a watch for silent-comedy buffs who are intrigued with the biographical drama of a career in trouble and an aspiring artist grappling uncertainly with daring material. As a director, Harry Langdon doesn't quite rise to the level of heroic failure, but his efforts to define himself are a kind of drama that eclipses his comedy. Who knows who'll actually laugh last?

5 comments:

"First of all, Three's A Crowd isn't an imitation of Chaplin, but a commentary if not a sardonic parody of the romantic Tramp. In simplest terms, the plot elaborates on themes Chaplin had played since The Tramp back in 1915. Langdon's film is the story of a hapless fellow, an assistant junkman who makes enough to keep his own apartment but is unfulfilled and lonely. He longs for a wife and child, adopting a doll briefly to toss in the air the way his boss tosses his own son."

I really have my fingers crossed that serious movie fans and partcularly fans of silent comedy will get over to MONDO 70 and indulge in this altogether spectacular piece. I am so imprssed with the writing, observations and historical insights that I am posting in the #1 position this week on the upcoming Monday Morning Diary. Langdom may be sadly forgotten orneglected by too many, but you have brought a fascinating comparative discussion here by Kerr and Kalat that's vindication of sorts in the examination of the famed THREE'S A CROWD and other works. Kerr's THE SILENT CLOWNS is indeed as you say here one of the greatest film volumes ever written, and one I do find myself going back to very often. (most recently in fact after the Film Forum's Chaplin Festival) And I do own that Landgon set on DVD.

"it may be that Langdon could have told his basic story nearly as well with a two-reeler."

Try editing out the entire solo-doll sequence, and then remove a few of the unnecessary and redundant shots in the pie scene and in the nightmare. Now the film doesn't "drag", and it seems close to perfect in its own perverse way.

A brilliant new book on Harry Langdon has just been published by Bear Manor Media. Here's the link and a press release by co-author Mike Hayde:

http://www.bearmanormedia.com/index.php ... uct_id=509

This is Harry Langdon's DEFINITIVE life story, coupled with the most comprehensive Langdon filmography ever compiled. My co-author, Chuck Harter, and I have uncovered every aspect of Harry's career, from his earliest stage appearances to his final day on a soundstage. Errors from previous books have been explained and corrected. Over 500 images add depth to the story of this most subtly visual of silent clowns. As a bonus, the book includes FIVE of Harry's original vaudeville scripts, TEN vintage movie magazine profiles from 1925-33, and a detailed, illustrated synopsis of HEART TROUBLE.

A Foreword by Steve Massa and a 3-page Introduction by Ed Watz - two of the most authoritative film comedy experts of our day - set the stage for this 690-page Langdon tribute. Whatever the depth of your interest in the Golden Age of Comedy, we're sure you'll enjoy LITTLE ELF.

--Michael J. Hayde

Here's the direct link to Michael and Chuck's new Harry Langdon book:

http://www.bearmanormedia.com/index.php?route=product/product&filter_name=Hayde&product_id=509

First of all, thank you Ed Watz for the two-fold plug for "LITTLE ELF" and thanks to MONDO 70's moderator for approving it.

After having worked on "LITTLE ELF," I believe a thorough understanding and appreciation of THREE'S A CROWD is impossible without knowing the events that had just transpired in Langdon's personal life. The film is at least in part an allegory of his experience with a long-time mistress, her estranged husband and a pregnancy she had terminated.

Post a Comment