Here's what vampires shouldn't be: pallid detectives who drink Bloody Marys and only work at night; lovelorn southern gentlemen; anorexic teenage girls; boy-toys with dewy eyes. What should they be? Killers, honey. Stone killers who never get enough of that Type A. Bad boys and girls. Hunters. In other words, Midnight America. Red, white and blue, accent on the red.

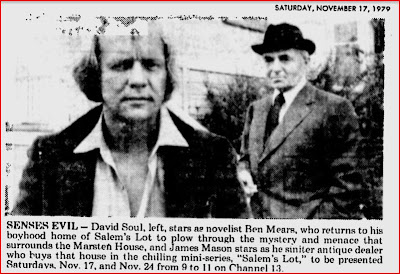

King had his chance at the vampire genre more than thirty years ago in Salem's Lot, his second-published novel and his first to be turned into a TV miniseries. I think it was also the first to be remade as another miniseries, but that's another story. My friend Wendigo and I took a look last weekend at Tobe Hooper's three-hour film, which was broadcast in two parts on consecutive Saturdays in November 1979, then condensed into a 112 minute theatrical release.

Kurt Barlow isn't exactly an American vampire, hailing from Europe as he does, but apart from that King's master vampire and the vampires he creates are straight killers, hunters who do whatever they have to to survive. In the novel, Wendigo tells me, Barlow is even less the newly-minted King type, more of a smooth talker and a seducer than the Nosferatu-inspired beast played by Reggie Nadler. But Barlow is never a "romantic" vampire, never the object of women's fantasies. He makes vampires but he doesn't get into the whole master-vampire thing. He lets some of his creations crash in his pad, but he seems quite indifferent to whether they fail or flourish. His only meaningful relationship is with Straker, his advance man, procurer, etc. They've traveled the world bleeding small towns dry, and the erstwhile Jerusalem's Lot is their next target. Are they drawn there by the Marsten House, a building thought by some (including our hero, Ben Mears) to be innately evil, or is there something about the people and their conflicts that Straker thinks Barlow can exploit? According to Wendigo, neither book nor movie ventures a solid answer.

Based on King's descriptions in the novel, Wendigo says that James Mason might well have played Barlow in a more faithful adaptation. But instead of portraying the vampire as a suave degenerate, the miniseries presents him as an inarticulate beast man, the producer feeling, no doubt under the influence of The Night Stalker, that a silent vampire was more scary. Wendigo thinks this approach undercuts both Barlow and Straker. In the novel, he says, the minion is almost a scarier character than the vampire, a "Renfield with attitude" who gives off a molester vibe in every scene. Mason is fine in the revamped role, but something's lost in the adaptation, not just his creepiness but the servility that helps put Barlow over as the real menace. In the miniseries Straker comes off almost like Barlow's keeper, and Barlow comes off as little more than Straker's trained animal. Wendigo says that Rutger Hauer and Donald Sutherland get vampire and minion more nearly right in the remake, though that project has plenty of problems of its own.Barlow (Reggie Nadler) brandishes some sharp claws while menacing Lance Kerwin, while Straker (James Mason) brandishes some broken furniture at his enemies.

The Marsten House

There are many more inevitable differences. The hero's love interest is a much younger woman in the novel, for instance, and her father and a separate doctor character have been merged in the miniseries. Mears himself (David Soul in the miniseries) isn't a newcomer to town in the novel, but had been away long enough that many residents take him for a stranger. The novel has a strong New England flavor that the miniseries mostly misses, and King has more time to build a more detailed, complex map of characters than Hooper has. King makes clear what Hooper can only hint at, that the town's moral rot makes it a perfect target for the vampire as much as the insularity that makes so many people reluctant to trust Mears's warnings about vampires. Salem's Lot is so caught up in itself and cut off from the rest of the world, Wendigo says, that you might believe that no one would miss it if it were wiped out. It's a more degenerate version of the small, endangered community of Whitby in Dracula, the novel King was inspired to adapt to an American context, and you get a stronger sense in the book that the population is getting wiped out rather than simply running away.

The town, seen from one of its more popular landmarks.

However much Hooper's miniseries deviates from King, Wendigo still likes it quite a bit. There are several things the director does very well. While turning Barlow into Count Orlok may be going too far, the look of the other vampires is appropriately rotten, discolored, dehumanized. Their power to bedazzle people has nothing to do with any innate glamour. It doesn't sound quite as cool as King's current description of the ideal vampire, but killers and hunters they certainly are.

Like I do, Wendigo well remembers the scenes of the child vampires floating up to the windows of their friends and scratching the panes. It's the same act an adult vampire will pull on an adult victim, but here you can't read any sex appeal into it. While those window scenes are the most memorable, there are also impressively creepy bits as a man is compelled to leap into an open grave, the better for a freshly buried boy to feed on him, and when he later appears to menace a victim while rocking in a chair.

Salem's Lot has some of the most ludicrous cross scenes, as vampires are repelled by the cross off a model tombstone and, most infamously, by two tongue depressors held together by surgical tape. But Wendigo thinks that these scenes effectively convey the ad hoc desperation of the newly-minted vampire hunters. I find the scenes interesting in the context of a priest's failure to repel Barlow with as official a crucifix as you can ask for. It shows that there are different kinds of faith, and that the faith in the existence of monsters and evil is more potent than simple faith in God. At the same time, the story seems to suggest that the existence of evils like Barlow is the most convincing argument for the existence of God for skeptics like Mears, who affirms the old saw that there are no atheists in foxholes.

Wendigo likes the acting with the arguable exception of an insufficiently energetic Bonnie Bedelia as the love interest. Some people may not think much of David Soul as an actor, but we find him nondescript enough that we accept him as Mears, not Hutch, for what that's worth. If anything hurts the project, it's the heavyhanded music that telegraphs menace for the most obtuse viewers. Ominous music swells whenever Mason takes a walk or a drive, as if to remind audiences during the slow first hour that something's supposed to be scary. That kind of telegraphing undercuts Hooper's distinct power to shock with sudden action. While the film gets better and scarier as it goes along, I actually found the most jump-inducing scene to be one without a vampire, when Mears is abruptly attacked by an ex-boyfriend of the Bedelia character. The last half-hour or so, I thought, was fine by any standard.

Normally when a Stephen King story gets its second adaptation it's meant to be closer to the source than the first try. Salem's Lot is an exception; Wendigo says that the remake is far less faithful to the novel than the Hooper miniseries, and just plain inferior as a story and a film despite a bigger budget. The Hooper, however, is a vampire film of a certain moment in time, just before the romantic vampire made its big move into the mass imagination. It's an advance technically on Dan Curtis's vampire tales and a departure from Curtis's tragic antihero characters, who probably had a greater influence in the long run. By now, and maybe by the time the remake was made, King's conception of the vampire as basically a bogeyman has become obsolete, his protests notwithstanding. It's hard to respect his complaint, since a vampire as a thing of fiction can be anything that suits our fancy, but there should still and always be room for the old-school unromantic vampire that many people now know only from Salem's Lot.

Here's the theatrical trailer as uploaded to YouTube by the no-doubt appropriately named TobeHooperFan.

4 comments:

This was one of those movies that really struck a cord with me as a youngin. I wanted to be Barlow! And I think he, in a way, forever ruined vampires for me. Cause I just can NOT get into non-monsterous vamps. I like my monsters to be monsters, not jerks in flannels running around the woods.

I hate to admit it, but I have to agree with King's assessment. The contemporary vampire isn't in the least bit scary, loathsome or fear-inducing. These "boy toys with dewy eyes" are just a sad statement on the average person's inability to deal with mortality.

Vampires are SUPPOSED to be monsters, not lovers. That being said, were I a vampire hunter, I'd much prefer to have to cross paths with the current wussy vampires than with a real monster, such as Orlock or Barlow.

Excellent blog.

Fancy the content I have seen so far and I am your regular reader of your blog.

I am very much interested in adding http://mondo70.blogspot.com/ in my blog http://the-american-history.blogspot.com/.

I am pleased to see my blog in your blog list.

I would like to know whether you are interested in adding my blog in your blog list.

Hope to see a positive reply.

Thanks for visiting my blog as well !

Waiting for your reply friend !!!!!

My own view on vampires, for what it's worth, is that they're fictional constructs. The form they take in the collective imagination reflects the mood of the moment. There's no objective or Platonic truth of vampires, so that while you can condemn any given project for bad acting, writing, etc., there's no basis for saying that it is "wrong" in its approach to blood-drinking immortals. If you have a problem with the prevailing presentation of them at any given time, your real problem is with the culture they come from, and you can judge that as you please.

Post a Comment