Bruce Chatwin's historically-inspired novel The Viceroy of Ouidah has a story worthy of a swashbuckling adventure from the golden age of Hollywood. It tells of a poor farmer who became a bandit only to be exiled to a foreign land where he overthrew a mad tyrant. Chatwin published his novel in 1980, long after the golden age. By then, it was a subject worthy of Werner Herzog, and a different kind of film resulted. Herzog predictably cast Klaus Kinski as the hero, which signalled that the character, the Brazilian bandit Francisco Manoel de Silva aka "Cobra Verde," would hardly be a hero. Whether Herzog's script and Kinski's performance reflects Chatwin's text, I can't say. I can say that, were that Chatwin's character, Hollywood would have whitewashed him into a more romantic, swashbuckling figure. Herzog presents him warts and all as an amoral rather than romantic figure.

Bruce Chatwin's historically-inspired novel The Viceroy of Ouidah has a story worthy of a swashbuckling adventure from the golden age of Hollywood. It tells of a poor farmer who became a bandit only to be exiled to a foreign land where he overthrew a mad tyrant. Chatwin published his novel in 1980, long after the golden age. By then, it was a subject worthy of Werner Herzog, and a different kind of film resulted. Herzog predictably cast Klaus Kinski as the hero, which signalled that the character, the Brazilian bandit Francisco Manoel de Silva aka "Cobra Verde," would hardly be a hero. Whether Herzog's script and Kinski's performance reflects Chatwin's text, I can't say. I can say that, were that Chatwin's character, Hollywood would have whitewashed him into a more romantic, swashbuckling figure. Herzog presents him warts and all as an amoral rather than romantic figure.Silva is no "social bandit" or revolutionary, no rallying point for the poor. Rather, Herzog shows him witnessing a mass whipping of prisoners in a public square with indifference. When one of the prisoners breaks loose, Silva stops the man in his tracks, basically telling him to go back and take his medicine. He impresses a wealthy plantation owner who doesn't know Silva's bandit identity. He hires Silva as his foreman, only to grow furious when the new man impregnates his half-caste daughters. Only then does Silva reveal himself as Cobra Verde. Rather than have him killed outright, the planter and his cronies give him a new job. They send him across the Atlantic to Africa to purchase slaves from the Kingdom of Dahomey. The trade has lapsed for many years and the king is rumored to be mad. No one really expects Silva to make good or even return alive. Once again they have underestimated their man.

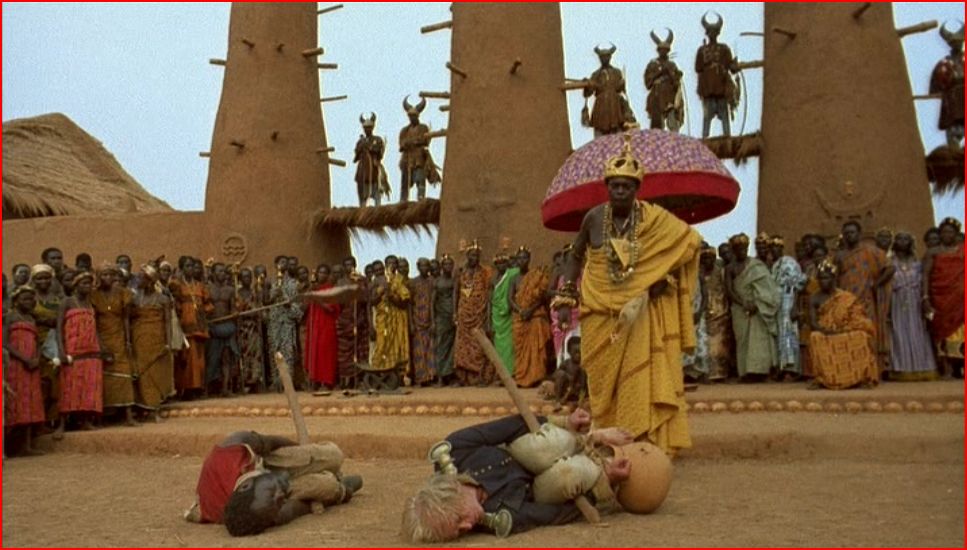

Against the odds, Silva revives the trade, exchanging men for rifles and taking residence in an abandoned fort. The Brazilians weren't kidding about the king, however, and Herzog warms to the challenge of having someone on screen crazier than Kinski. The king demands to see Silva, but the trader demurs, insisting that he must always have one foot in the ocean -- he must stay on the coast. The king's men simply kidnap him; respecting his obligations, they fill a jar with sea water and stick his foot in it. At court, the king asks after the health of his peers, the crowned heads of Europe, then asks why Silva has gathered a fleet of several hundred thousand ships to invade his country, and why Silva has poisoned his pet.

Silva has a lucky escape and joins a conspiracy to replace the king with a bug-eyed, perhaps equally mad yet more compliant relative. Now at last Silva is the kind of rebel you would expect to see in a swashbuckler. He is tasked with training an army of topless women, the men of the land having proved unreliable. He shows them how to fight with spears and ferocity. This is where most people will put in a screencap of Kinski grimacing and brandishing a spear. Thanks to them, I don't have to; google it if you like.

An army of bare-breasted Amazons is a natural Herzog subject, and as in all his pictures there are plenty of sidewise glances at small details that make scenes more real (animals) or more weird (crippled people). He manages an impressive level of human spectacle in the Amazon scenes and the scenes at the king's court, where skulls are the popular design motif. He might be accused of objectifying the Africans as savages had he not established Silva as no more than a savage himself. If anything, Herzog objectifies humanity as savage or, at best, pitifully grotesque. There's something uncomfortably exploitative in his having Kinski attended in the film's final scenes by a handicapped man who walks more like an ape than a man, propelling himself with strong arms while withered legs drag behind, but by now you also understand that the grotesque is a reality principle for Herzog. Addressing slavery, Cobra Verde slightly resembles Jacopetti & Prosperi's Goodbye Uncle Tom in its gruesome pretensions of objectivity. To many it will seem cold if not hateful. Kinski's character has no arc of development, learning or enlightenment. Like many a movie gangster, Silva simply rises until he falls, without really enjoying his rise in the ways that endeared gangsters to guilty moviegoers. Silva does remarkable things but barely counts as an interesting person. Instead of rebelling against injustice, he embraces it at the first opportunity and arguably embodies it. This is Herzog at perhaps his most misanthropic. It's a legitimate worldview, but few will like it.

As for Kinski, he may finally have been getting too old for this shit. He gives a mostly sullen performance, albeit one appropriate for the character, and this is probably just what Herzog wanted from his longtime collaborator and "best fiend." You feel for him, however -- the actor, not the character -- as Herzog has him struggle to drag a boat off a beach while the tides punish him and the human quadruped watches. Sympathy isn't what Herzog wants, however. If you can sit through a picture without needing to sympathize with anyone -- I'm such a person myself so don't take this as a rebuke -- you may well be impressed with the epic rigor of Herzog's historical vision. It is quite a show and I was duly impressed, but if you finish the film with a shrug or a scowl, I can't really blame you -- and Herzog might not, either.

1 comment:

Great write up, Sam. I assume this is in that Herzog box? I saw it on amazon and was eyeballing it with the intent to buy.

Post a Comment