I

In 2009 Leisure Books, one of the leading publishers of paperback westerns, issued "The Classic Film Collection" of novels that had inspired great western movies. Titles included Max Brand's venerable

Destry Rides Again, T.T. Flynn's

The Man From Laramie, Forrest Carter's

Gone to Texas (filmed as

The Outlaw Josey Wales) and two by Alan Le May.

The Unforgiven was filmed by John Huston with Burt Lancaster, Audrey Hepburn and Audie Murphy in 1960. Four years earlier, John Ford had made Le May's

The Searchers into a film widely regarded as the greatest of all western movies. The film's reputation made the novel worth a read. It would at least be interesting to see how much Ford and his screenwriter, Frank S. Nugent, deviated from the original text, and whether the book could stand comparisons to the film.

The first thing a reader notices is that Le May starts his novel at approximately the 14-minute mark of the movie. He opens with Aaron Edwards noticing suspicious signs near his homestead while his visiting brother rides with Martin Pauley and the locals in search of cattle thieves. He cuts from the Edwards homestead to the men on the trail and back, until the family sends little Debbie out back to hide near Grandma's grave. Le May does

not show an Indian discovering the girl and blowing a horn. For the moment, Debbie's fate is even more mysterious than in the movie. But the important fact for comparison's sake is that the first scenes of the

Searchers movie are complete inventions of Ford and Nugent. What do they add to Le May's story?

Some people may know that Aaron Edwards's vengeful brother is called Amos, not Ethan, in the novel. The change seems like one of those infuriatingly arbitrary Hollywood decisions, though you might speculate that Ford liked the alliterative sound of "Ethan Edwards" better, or that he thought the name Amos too evocative of

Amos n' Andy to be taken seriously. There are a lot of arbitrary changes for the film. The novel's Mose Harper is a garrulous old man with grown sons, a bit of a bore when he bloviates about the past but neither crazy nor stupid by any means. But there's a character named Lije Powers who becomes more important late in the story and wants no more payment for his help in the search than to have a bunk to sleep in for the rest of his life -- and a rocking chair. Ford and Nugent merge the two characters into a personality suited to stock-company stalwart Hank Worden. The neighbor family to the Edwardses is the Mathisons in the novel. Ford makes them the Jorgensons for no better reason than for John Qualen to do his Swedish accent. Qualen could do perfectly well without the accent; his greatest performance, arguably, is done without it in

The Grapes of Wrath and was directed by John Ford. But one suspects that Qualen's Swede schtik makes

The Searchers more superficially Fordian, as does the expansion of a Texas Ranger commander's role to suit the bluster of Ward Bond. But the transformation of Amos into Ethan Edwards is more than superficial, more than Fordian gimmickry.

Amos Edwards "had served two years with the Rangers,and four under Hood, and had twice been up the Chisholm Trail. Earlier he had done other things -- bossed a bull train, packed the mail, captained a stage station -- and he had done all of them well. Nobody exactly understood why he always drifted back, sooner or later, to work for his younger brother, with never any understanding as to pay." He is prone to "deadlocks" that may explain his restlessness. Such a deadlock leaves him torn between rushing back to Aaron's land once convinced that the raiders may strike there and continuing with the chase of the presumed cattle thieves lest he seem a coward to the other men. But this is only what Martin Pauley assumes. In the novel, Amos is seen entirely through Martin's eyes. The novel itself is Martin's story more than anyone else's. The film is Ethan's. That's why Ford shows him arriving at Aaron's place and establishes his relationships with the people there, from the three-way tension with Aaron and his wife Martha to his casual hoisting of little Debbie into the air. If the novel always shows us Martin watching Amos, the film strives for balance, giving us Ethan's perspective as well as Martin's. The film is full of powerful reaction shots of John Wayne's Ethan as he despairs or seethes with rage or gazes with revulsion at some new horror. The part probably had to grow to fit Wayne's stardom, but as is well known, Ethan Edwards is someone quite different from the typical John Wayne hero role.

If Le May presents an existentially indecisive Amos, tormented by his failure to claim the woman he loved, who dies his brother's wife, Ford gives us an all-too decisive Ethan. The mystery about Ethan Edwards isn't why he never sticks with any job, but whether he's robbed a bank or a train. Ethan's problem isn't indecision; it's an irreconcilable nature that doesn't believe in surrendering (he professes continued loyalty to the defunct Confederacy) and doesn't accept contradiction. His relationship with Martin has sharper edges. In the novel, Martin is described as dark, but he doesn't appear to have as much Indian blood, if any, as the movie Martin. He bristles in the book when someone says he looks like a half-breed. In the movie, his mixed ancestry gives Ethan reason to despise him. Much of their banter is carried over verbatim from book to film, but it comes across meaner in the movie. Partly that's because the movie Martin is a much weaker character than the original. Ford and Nugent make him much more of a tenderfoot than he is in the novel. While Martin is clueless in the picture about Ethan's intention to use him as bait to lure Jerem Futterman into an ambush, in the novel he argues with Amos about how much of a dumb "old flim-flam" the idea is. If the movie Martin is more naive, Ethan is more masterful than Amos. In the movie, he shoots down a Ranger's idea of stampeding the ponies of the murder band by noting the old Comanche trick of sleeping tied to your fastest pony. In the novel, stampeding the ponies is Amos's idea, and it's shot down by Charlie MacCorry (portrayed as an imbecile in the movie). As the difference in skill and power appears more vast in the movie, so Ethan appears more intimidating to Martin and the audience.

Above, Jeffrey Hunter and John Wayne. Below, this scene is as defiant as Martin Pauley gets in the picture. In the novel, he cooly tears up the will and warns a healthy Amos that he'll kill him if he gets Debbie killed -- and Amos backs down. That'll be the day....

Make no mistake: Amos Edwards is as much of a menace as Ethan as far as a grown-up Debbie is concerned. Amos is just as ready to destroy her rather than see her degraded as a squaw, but his attitude is taken as a given, explained only by Martin's speculation about the man's grief over the woman he loved but never had. His attitude doesn't even seem to be exceptional: Laurie Mathison tells Martin that killing the adult Debbie would be the right thing to do and something her mother would have approved. But because Ethan Edwards is the central character of the

Searchers movie, Ford feels a need to explain the depths of Ethan's hatred. He had Nugent write an original scene, one of the most controversial scenes in the picture, in which Ethan and Martin inspect some white women liberated from Indian captivity. They appear to have been driven mad or retarded in their mental development. Their behavior is infantile or subhuman. And Ford makes sure with a dolly shot moving in for a close-up that we see Ethan take it all in and let it stew in his mind. Ford shows us what Ethan is thinking in a way Le May never directly shows us Amos thinking.

Ford's

Searchers is recognized as a critique of one man's racism but also widely viewed as itself racist given scenes like that one. How racist the film really is might be measured by comparing it with the novel. The savagery of Indians is more of an overriding topic of Le May's novel. Le May's racism isn't genocidal, but it is judgmental. He attributes to Native Americans the classic characteristics of the savage enemy or "unlawful combatant." They abuse the good will of naive humanitarians. They push the envelope constantly to see what they can get away with before the military cracks down. Above all, they lie and lie and lie. The author's viewpoint, as best as I can tell, is that they need to be tamed, not exterminated. His characters see things differently.

"Look," Martin's accidental Indian wife, is one Native character treated with more respect in Le May's novel than in Ford's film -- but Ford milks her demise for more pathos and more outrage against his usually irreproachable U.S. Cavalry.

"I see something now....I never used to understand. I see now why the Comanches murder our women when they raid -- brain our babies, even -- what ones they don't pick to steal. It's so we won't breed. They want us off the earth. I understand that, because that's what I want for them. I want them dead. All of them. I want them cleaned off the face of the world."

The speaker is Martin Pauley, and what provoked this wasn't some fresh massacre or any act of violence. His comments to Charlie MacCorry come after he has finally found Debbie and she has urged him to go away. It's a much more protracted scene than in the movie, and the gist of it is that Chief Scar's Comanches have brainwashed Debbie. They've convinced her that Scar rescued her after other Indians or white rustlers killed her family. They have her believing that all white people lie. This concern with brainwashing or indoctrination, on top of Le May's contemptuous account of all attempts to appease the Indians, gives the

Searchers novel a sort of Cold War quality, with the Comanches standing in as much for Communists as for archetypal savages. Stories of Indian captivity probably seemed especially relevant at a time when "Better Dead Than Red" was a watchword. Indian stories probably gave Cold War audiences a politically safe way to ask and answer whether dead was better than red after all, though

The Searchers leaves open a none-of-the-above option. For the record, the novel allows readers to believe that Debbie may still be a virgin when the heroes find her. Scar is her "father," not her husband, and is unwilling to trade for her because he's already arranged a marriage for her that will net him a fortune in horses, and reneging will cost him face in his tribe. The movie, meanwhile, never refutes the assumption that Debbie has been "living with a buck," and thus states more firmly that it could never be too late to rescue her. "Better Dead Than Red" in the other sense of red is not an option in the film. In any event, for both book and film it might be helpful to distinguish between racism and bigotry. That distinction might also help us resolve the apparent contradictions in the film. A story might be racist while indicting bigotry if the latter is defined as an individual's irrational hatred while the former merely presupposes superiority, inferiority, conflict and conquest. More so, arguably, than Amos, Ethan is a bigot. Hatred is a personal issue that he has to overcome. In Ford's film, that overcoming becomes the central dramatic event, more important than whether Debbie is ever found since, if he doesn't overcome himself, Debbie will surely die.

Ford's build-up to the big reveal of Natalie Wood as the grown Debbie is something film can just do better than writing. Max Steiner's outstanding score helps a lot.

The stakes aren't that high in the novel. The biggest departure the film makes from the novel, after all, is that Ethan spares Debbie. In the novel, Amos never gets the chance. After a much more elaborate battle scene than in the movie, Amos prepares to ride down a fleeing squaw he presumes to be Debbie while Martin calls out for him to stop and actually takes a shot at him. At the last moment, Amos simply grabs the girl -- at which point she reveals herself as a Comanche and shoots him to death at point blank range. It's up to Martin to find Debbie wandering in the desert well after the battle, with the slightest closing hint that they might form a couple later. Martin is available because, in the novel, Laurie Mathison marries Charlie MacCorry after all -- you couldn't expect her to wait forever, could you?

The end of the novel can't help but seem anticlimactic in light of the movie because Le May doesn't really give us a redemptive moment. We do not see Amos overcoming his hatred -- he may simply have had one last deadlock of indecision and paid for it. In the film, however, Ford has prepared us for the supreme moment from the start, from the early shot when Ethan hoists little Debbie in the air. When he lifts Natalie Wood's adult Debbie the same way, our memory of the earlier scene allows us to assume a similar memory at work in Ethan himself. She is the child once more, not the squaw. But Ford's famous finale, in which Ethan turns and walks away instead of joining the big reunion at the Jorgenson place, could be his act of fidelity to the novel, his admission that the Edwards character has been destroyed by his quest after all, despite his apparent redemption, reduced to walking between the winds like a living ghost -- as Debbie does in the novel's closing pages before Martin finds her. Maybe -- maybe -- Ethan felt a twinge of remembrance of Martha Edwards, too, and could not stay under the same roof as an adult Debbie with that feeling in him. The way Le May subtly sets the stage for a quasi-incestuous union of Martin and Debbie makes such a reading of Ford's adaptation slightly more plausible.

Alan Le May's

The Searchers is a crisp read, largely free from purple prose. His sound ear for dialogue is honored by Nugent's echoing of almost entire paragraphs of dialogue from the novel -- though sometimes different people say the words. A well-known speech given to Olive Carey's Mrs. Jorgenson about the ordeals and resilience of Texans, for instance, was originally uttered by Amos Edwards, in an especially pensive mood, after he discovers (as we learn in retrospect) Lucy Edwards's body. For all his apparent disdain for Indian cultures, Le May doesn't write comic-book Indians; his Native characters always feel like distinct individuals within the parameters of unprincipled barbarism.

The Searchers isn't the best western novel I've read -- that's still Oakley Hall's

Warlock -- but I'd still recommend it. I'd even say it'd be worth someone's while to make another movie of it. It worked for

True Grit, after all. Honestly, it'd be interesting to see the story shot from Martin's perspective as it is in the novel, and there are scenes in the book that Ford never filmed but are nevertheless potentially cinematic. Above all, there's an amazing scene in which Amos and Martin race for shelter as a blizzard bears down on them that was probably beyond Ford's resources but could certainly be done justice now -- probably only Akira Kurosawa could have done it justice in the past. But the point of a remake would not be to top John Ford, and I don't mean to imply that his

Searchers inadequately represents the novel. In fact, it's an exemplary cinematic enhancement, a classic of creative adaptation. Ford and Nugent tighten the story effectively in many spots, reducing the number of visits to the Mathison/Jorgenson farm, for instance, to maximize the dramatic impact of each return. Since there's no time limit on reading a novel, Le May can take his time and work through more false leads than a movie audience might tolerate. He can't match Ford at his best for dramatic editing, ingenious framing of action, and the overwhelming power of those Monument Valley locations in VistaVision. Le May doesn't have Max Steiner's score to underline and highlight key moments, either; the veteran composer's old tricks work as well as ever here. Le May may be a formidable storyteller, but Ford is simply a better picture maker than Le May is a wordsmith. Many of the memorable words in the movie may be Le May's (though not "That'll be the day..."), but the indelible images of

The Searchers, and the life they give to Ethan Edwards, are Ford's alone. His film may not be the greatest western (let me get back to you on that), and it may be too "Fordian" for its own good in some ways, but it is a masterpiece and would remain so no matter how many times the novel is filmed.

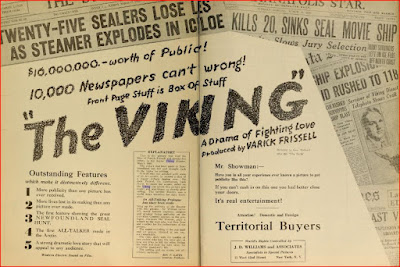

The French have a term, "film maudit," for "cursed" films, by which they and film buffs everywhere mean those movies that suffer from difficult productions and/or box office rejection. By some standards, Andrew Stanton's John Carter qualifies as a film maudit because of the critical drubbing it's received and the abysmal losses it now represents for the Disney company. However, if we were to consider George Melford's The Viking a film maudit, few other films would merit the label. This early Canadian talkie may be the ultimate film maudit, not just for the horrific circumstances that ended the production, but for the way the film itself seems in retrospect to court doom. It was released in the summer of 1931, its title changed from "White Thunder" in an act of ghoulish exploitation. The Viking was the name of the vessel, a real working ship, that took cast and crew to the Labrador ice fields to film the seal hunts on the ice. After a preview of "White Thunder" played poorly, producer Varick Frissell ventured back to Labrador (without Melford, as far as I know) to shoot more actuality action scenes. On that trip, the explosives kept in store for ice breaking blew up on board, killing Frissell, his cinematographer and two dozen others. The story is told in a preface to the picture proper, following a title card that fairly identifies the event as the greatest catastrophe in the history of motion pictures. It so happens that The Viking is a film about a hero considered a jinx -- or "jinker" in the local slang -- who sails with the title vessel against the will of a captain who boasts that he's never lost a man on any expedition. That actor was the real captain of the Viking during the initial filming. He didn't sail on the fatal return trip, but his mate did, and died.

The French have a term, "film maudit," for "cursed" films, by which they and film buffs everywhere mean those movies that suffer from difficult productions and/or box office rejection. By some standards, Andrew Stanton's John Carter qualifies as a film maudit because of the critical drubbing it's received and the abysmal losses it now represents for the Disney company. However, if we were to consider George Melford's The Viking a film maudit, few other films would merit the label. This early Canadian talkie may be the ultimate film maudit, not just for the horrific circumstances that ended the production, but for the way the film itself seems in retrospect to court doom. It was released in the summer of 1931, its title changed from "White Thunder" in an act of ghoulish exploitation. The Viking was the name of the vessel, a real working ship, that took cast and crew to the Labrador ice fields to film the seal hunts on the ice. After a preview of "White Thunder" played poorly, producer Varick Frissell ventured back to Labrador (without Melford, as far as I know) to shoot more actuality action scenes. On that trip, the explosives kept in store for ice breaking blew up on board, killing Frissell, his cinematographer and two dozen others. The story is told in a preface to the picture proper, following a title card that fairly identifies the event as the greatest catastrophe in the history of motion pictures. It so happens that The Viking is a film about a hero considered a jinx -- or "jinker" in the local slang -- who sails with the title vessel against the will of a captain who boasts that he's never lost a man on any expedition. That actor was the real captain of the Viking during the initial filming. He didn't sail on the fatal return trip, but his mate did, and died.