Browning's Dracula is regarded as the first Hollywood film to feature an actual supernatural menace, one that isn't proven a fraud at the end of the picture. I'm not sure that that's true; there has to have been some movies with real ghosts during the silent era. But I can see why it seemed that way in 1931, when debunking movies like The Cat and the Canary and Browning's own pseudo-vampire story London After Midnight were fresh in memories. Because he'd made London (in which Lon Chaney is a detective who dresses as a vampire to catch a human villain), Browning seemed determined in Dracula to leave no doubt in viewers' minds. He shows us Dracula and his brides rolling out of their coffins to anticipate Renfield's arrival at the castle, which made me ask Wendigo why Browning wasted the opportunity to create suspense by making us figure things out as Renfield does. The point, Wendigo said, was to do without suspense, to put it in your face that Dracula is an undead, unnatural being, and that there were new rules in the horror genre.

Browning's Dracula is regarded as the first Hollywood film to feature an actual supernatural menace, one that isn't proven a fraud at the end of the picture. I'm not sure that that's true; there has to have been some movies with real ghosts during the silent era. But I can see why it seemed that way in 1931, when debunking movies like The Cat and the Canary and Browning's own pseudo-vampire story London After Midnight were fresh in memories. Because he'd made London (in which Lon Chaney is a detective who dresses as a vampire to catch a human villain), Browning seemed determined in Dracula to leave no doubt in viewers' minds. He shows us Dracula and his brides rolling out of their coffins to anticipate Renfield's arrival at the castle, which made me ask Wendigo why Browning wasted the opportunity to create suspense by making us figure things out as Renfield does. The point, Wendigo said, was to do without suspense, to put it in your face that Dracula is an undead, unnatural being, and that there were new rules in the horror genre.Dracula is a vampire -- a nosferatu, as some peasants and academics say. What of it? What is a vampire, exactly? Most American moviegoers, given the rarity of Murnau's Nosferatu, had never seen a "real" vampire. What, then, do they learn from Browning and Bela Lugosi?

Which of these three doesn't belong?

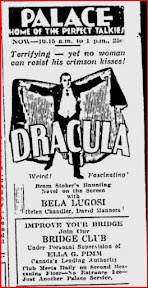

Bela Lugosi played this character, a repulsive monster, on Broadway and became a sex symbol. How did that happen? Part of it had to do with his famous accent, which made him a counterpart of the "Latin Lovers" who were popular during the Twenties -- though in silent movies you couldn't hear the accents. There was a bit of the "demon lover" in the Latin Lover, something savage and dominant -- think of Valentino as The Sheik. Think of Valentino as Dracula, for that matter, had he lived. Plausible? If so, that may clarify the connection between the vampire and the Latin Lover. For female audiences, both offered a rape fantasy of sorts that was made safe by being fictional, even if the vampire's rape threatened a fate literally worse than death.

Sex appeal makes Lugosi's Dracula something very different from the ugly horrors of Nosferatu and London After Midnight, but Wendigo reminds me that in folklore the word nosferatu means an incubus who sexually ravishes women until they die of exhaustion or become pregnant by the creature. So sex has always been there, Wendigo suggests, but women weren't going to imagine welcoming Max Schreck into their beds. Lugosi adds sex appeal to the sex. He dresses well and displays a Romantic if Gothic sensibility ("To be truly dead...that would be glorious"). At the same time, Wendigo emphasizes the way that Lugosi conveys with his slowness, his labored English ("to-morrow...eve...nink.") and his glacial, deliberate movements, that he is a dead thing. We've seen other Lugosi films from 1931 where he moves more energetically and speaks English much more easily than in Dracula, so we can conclude that his manner of speaking the lines he's known for years is a deliberate choice. Slowness also symbolizes sleep, hypnosis and somnambulism, and his victims (most notably his brides) become as slow as Dracula. Under his influence, Mina thirsts for Jonathan Harker's blood, but doesn't pounce with fangs bared as in a modern vampire film. Instead, she closes in oh so slowly as the camera closes in in another instance of Browning's (and Karl Freund's) underrated facility with the camera. The slowness identifies her and Dracula as not of this world.

Helen Chandler as Mina, with a lean and hungry look. David Manners

may as well have his back to us throughout the picture.

Lugosi's undead sexiness is, most significantly, a synthesis of the folkloric vampire and the pop-culture vampire, two very different things that had been competing for attention for decades before the Hamilton Deane-John R. Balderston play and the Universal adaptation began to merge them. In the very year when Bram Stoker published the novel Dracula, Rudyard Kipling published "The Vampire," which was inspired by Philip Burne-Jones's painting of the same name. Poem and painting described a man drained of life force by a predatory female who was not a bloodsucker but a kind of moral succubus.

The poem's opening words, "A fool there was," became the title of Porter Emerson Browne's play and nove that, as a 1914 movie, made Theda Bara one of Hollywood's first true stars. Bara's star persona was the "vampire." The subsequent diminutive, "vamp," which survives today, doesn't convey the malignancy imagined by Kipling and subsequent writers.

If someone used the word "vampire" in the media from 1897 until 1931, they were less likely to have meant someone like Dracula than someone like Theda Bara. Bram Stoker's legacy was lapped by Kipling's almost as soon as both were out of the starting gate. Wendigo observes, however, that the pop-culture vampire archetype I've described reminds him a lot of Sheridan LeFanu's Carmilla, while Bara's habit of striking batlike poses at least evoked a supernatural lineage for her mundane menaces. What Balderston, Deane, Browning and Lugosi did with Dracula was integrate the seductive aspect of the pop vamp with the traditional supernatural monster -- with a lingering pop fascination with mesmerism (Svengali reached the screen the same year as Dracula) thrown in. After the movie, when people spoke of vampires they were once more more likely to mean the undead than gold-digging maneaters. That's a little cultural revolution right there.

The bat effects in Dracula aren't really bad for a first try.

It all sounds good on paper, but it was up to Browning, the recognized master of cinematic grotesques, to sell it. His direction of Dracula has a bad reputation, mainly because he mostly stuck with the play's centralization of action at the Seward house. Critics give him credit for an atmospheric first half hour, while Renfield travels to Castle Dracula, but act as if the camera simply froze once the vampire reached London. Browning has suffered even more since George Melford's Spanish-language version returned to mass circulation, but Wendigo and I agree that the English-language version gets a bad rap. Looking at the main action with reviewers' eyes, we noticed how frequently Browning moves the camera in the dreaded drawing room, how often he dollies in and out for emphasis, and how often he stages the action to let actors walk toward the camera or retreat from the camera for maximum dramatic effect. Also, Browning doesn't need as many fancy directoral tricks to hold your attention as Melford does, because Browning has Lugosi. Any sensible director of Dracula would film Lugosi the way Fred Astaire preferred to be filmed, because Bela acts with his whole body and needs to be seen occupying the same space as his fellow actors in order for his timing to work. Browning doesn't need to impose an auteurial signature here; the story itself is enough to mark this as a typical Browning film for his fans.

Art direction by Charles D. Hall

Browning enjoys a definitive cast of supporting players.

Dwight Frye is Renfield. He's a more important character than in the novel, based on the writers' need to tie the madman more closely to the main plot. He takes Harker's place on the trip to Transylvania (which reduces David Manners's Harker to a near nonentity) and is stuck in a situation where the audience knows more than he does. He holds our sympathy with his determined politeness, but once under Dracula's sway he blossoms into one of movies' great madmen, as well as a faithful-enough embodiment of Stoker's "sane man fighting for his soul." Nearly everyone admires Frye's mad scenes and his incredible laugh, but Wendigo feels that he deserves more credit for a more fully nuanced performance that encompasses compassion and moral terror as well as insane arrogance and craven servility. Frye's Renfield may persist as an archetype for actors even longer than Lugosi's Dracula.

Sorry, Hammer fans, but Edward Van Sloan is Van Helsing. Peter Cushing does a great version of the character, but Van Sloan embodies pure willpower in a manner Cushing never matched. Here a character's slowness (compared with Cushing's dynamic performances) expresses indomitable authority. The scene where Van Helsing stares down Dracula despite the vampire's full exertion of his dominance is an awesome moment. Van Sloan portrays a man who takes no shit from anyone, dead or alive. Dracula has heard of this guy, Bela tells us, but still underestimates him. Van Helsing's virtues are willpower and knowledge, a point sometimes missed by Cushing and entirely lost by (ugh!) Hugh Jackman in a recent travesty of the mythos.

Dwight Frye sets the tone for generations of viewers dissatisfied with Charles Gerrard as Martin.

Van Helsing tells us that he will turn the superstitions of the past into the scientific truths of today by revealing a vampire's existence. This assertion helps us understand why some other characters in the movie annoy people so much. Probably the most hated person in the picture is Martin, the sanitarium keeper and "loony" catcher. Martin's only response to any outburst from Renfield, no matter how revealing it might be, is to reiterate that he's a loony. He grows convinced by the end of the film that everyone but himself is loony. In simplest terms Martin is comedy relief on the Shakespearean model of an ignorant smart-aleck, but for Dracula's purposes he represents the far extreme of unwillingness to believe the increasingly obvious. Wendigo adds that comedy-relief characters and scenes serve a necessary release-valve function, breaking up the tension of the plot so that the next shock will be a fresh jolt. Next most obtuse is poor Jonathan Harker, who scoffs and sneers at Van Helsing's notions until Mina's teeth are practically in his throat. David Manners' very name may have destined him to play bland heroes, but he can't be blamed for a thankless role that reduces the hero of the novel to a clueless observer of events. We want him to figure it out, but we might just take him for a stubborn skeptic if we didn't have Martin around to show us that Harker's viewpoint is just plain stupid.

Wendigo suggests, however, that Harker's ignorance may be a necessary component of his innocence. He notes that, even after Harker realizes the truth, he never becomes such a vampire hunter that he has blood on his hands. Wendigo's impressed by the final symbolism of Harker escorting Mina up the great staircase out of the Carfax crypt, as if he were guiding her out of the underworld into which the fallen angel (Dracula) had driven her. Harker has to retain a sort of innocence in order to fulfill this function, but viewers might be excused for finding him a little too innocent to be respectable.

The Browning Dracula remains one of Wendigo's top ten vampire films. It holds up well after eighty years, and Wendigo sees fresh details and nuances every time he watches it. Because it's a consciously trailblazing film, it retains a certain transgressive quality no matter how tame the action may seem compared to so many later vampire films. Wendigo has never read the play, so he can't be certain how much Browning really contributed, but the director was probably the right man for the moment. When I asked him what Dracula has that so many later films lack, he told me that it might be the simplistic answer, but "Bela Lugosi" is the correct one. He has "it," as might have been said of a contemporary "vamp," and it sticks with us today. No matter how many have followed him in the role, Dracula still speaks to the collective consciousness in Lugosi's voice. Wendigo will not say that this is the best vampire film ever, but it'll always be in the running. For my part, when asked by Wendigo, I won't claim it's the best either, but I will say it still sets a standard for the genre. The others are all variations on Dracula's theme.

Here's the familiar Realart re-release trailer, uploaded to YouTube by RoboJapan.

8 comments:

This is an incredible post, one of the best I've read on this Dracula. I'd never thought of how the pop-cultural connotations of "vampire" changed with this movie! I have heard Chaney was set to play the role in the film, but died before production, so Lugosi was then chosen. Not sure if that's true or not.

How many times did we all see "Dracula" on TV as children? Plenty. I will agree with Wendigo's assertion that Lugosi's interpretation of Dracula puts the film in an upper echelon.

I've seen "Bram Stoker's Dracula" (1992). That was 2 hours I'd never get back. I've seen "Van Helsing" w/Hugh Jackman in the title role, and it's not his fault that film went in the tank. Hollywood's current generation of screenwriters couldn't leave well enough alone with tradition, turning Van Helsing into a werewolf to fight Drac. Just an excuse to empty out the CGI budget is all it was.

Now, I've never seen "Nosferatu", save for the obligatory clip used in a Queen video ("Under Pressure"). I think Stephen King used that as his inspiration for "Salem's Lot"'s lead vampire (if you've got that on DVD, Sam, check it out and you'll see what I mean). In truth, Lugosi still is the definitive Dracula, no matter how many times Hollywood wants to screw around with the character.

Will: From what I've read, Chaney was desired by Universal but the studio wasn't in a position to offer M-G-M anything in exchange for his services. He was already out of the running by the time he died. I don't think the movie would have had the same impact if Chaney had done it, unless he was ready to do something different from his usual grotesques.

Hobby: On the Nosferatu/Salem's Lot connection: well, duh! And the Murnau is one you need to see if you want to talk about cinema vampires.

Well, as for King's 'Salem's Lot, his inspiration was the original Stoker novel; the Nosferatu-looking character in the '70s TV movie was made up by the producers. In the novel that character--Barlow--is a European aristocrat, nothing monstrous about him.

Will, thanks for the clarification. I was thinking visually of Murnau's influence on Tobe Hooper rather than Nosferatu's influence on King himself.

Incredible post, as Will Errickson said. It's become kind of "critical cool" to dis Browning's direction here, but I really believe that's just a fad. There's a reason this movie has stood the test of time, and its place in history is only part of it.

And thank you for pointing out the often neglected contribution of Edward Van Sloan here. I've always had him at the top of my "Van Helsings" list, but never articulated the reasons why as succinctly and precisely as you do here. One of my favorite scenes in the movie--or in all the Universal Horrors, for that matter--is the show-dwon between Dracula and Van Helsing over the mirrored cigarette case. Lugosi is flawless here, shot in the "Astairean" way you suggest, as he goes slowly from the look and aspect of a cornered animal--look at his face, it's really a shocking mask of viciousness--and then slowly, oh so slowly regains his composure and control. But Van Sloan's set-up, the knowing offering of the cigarettes, the delivery of the line--it wouldn't be half the scene without it.

Lugosi and Van Sloan have remarkable chemistry too. The line that ends that scene--"You must...forgive me. I do not like...mirrors. Van Helsing...vill explain."--gives me chills, but it's the respect Dracula offers grudgingly--"For one who has not lived...even a single lifetime...you are a wise man, Van Helsing"--that's EARNED, buddy!

Finally, it's nearly impossible to overstate how Lugosi's sex appeal you describe forever changed the character of Dracula. In the book, Dracula's attacks on the heroines were not seductions--they were rapes, pretty much explicitly (hence all that talk of Mina being "tainted" taking on added subtext); it was only with Lugosi that they became seductions, the victims almost willing accomplices.

I could go on and on, but I'll stop there and congratulate you on another excellent essay. Kudos!

This is a spectacular consideration of this famous film, one that has spawned a host of imitators over the years. It's doesn't match Murnau's NOSFERATU (it's too stagy and it takes some serious liberties with the source material)but it has one of the cinema's greatest opening segments, and it's atmospherics are legendary. You've examined the film from so many angles here, and the commentators are rightly animated.

I did see the Phillip Glass version in a theatre several years back and was again ravished from yet another perspective.

Vicar, thanks for bringing up the mirror scene because it highlights both Lugosi's brilliantly calibrated performance and Browning's use of the camera to follow him, come in close, then pull back as the Count reminds himself of where he is and the need to maintain appearances. My screencap of Van Sloan, you may have noticed, comes from just after Dracula has made his apologies and left the room. He looks rightly satisfied with himself.

Sam J., I hope my review encourages you to rethink Dracula's staginess, though I admit the location remains an inherent limitation. When it comes to cinematic Draculas, the question is what liberties are taken and how they compare with other versions. In such a comparison Browning may come out relatively well.

By the way, Sam's comment gives me an opportunity to tell the horror fans among my friends and followers that his blog, Wonders in the Dark, is hosting a Top 50 Horror Film countdown starting next week. If it's anything like the decade countdowns that have appeared there over the past year or so, the choices should be interesting and the debates lively.

Post a Comment