Jacinto Molina died one year ago this week but on film he lives on as Paul Naschy, the last of the old-school horror men, an interpreter of the classic monsters who translated the naive fantasies of Universal Studios into the idiom of Seventies exploitation without losing the original sense of wonder. To mark the anniversary of his passing I'm contributing to a memorial celebration blogathon coordinated by the Vicar of VHS and the Duke of DVD of Mad Mad Mad Mad Movies fame, but I fear that my tribute isn't all it could be. That's because I chose to watch Leon Klimovsky's Dr. Jekyll y el Hombre Lobo in a version provided by Mill Creek Entertainment as part of its new Pure Terror collection. In its original form, the film is 96 minutes long. Mill Creek's version is barely 72 minutes; more than a quarter of its running time is gone, including the opening credits. The remainder is an awkwardly disproportionate film that feels like two separate projects grafted together and leaves you wondering for the longest time when Dr. Jekyll might show up.

Jacinto Molina died one year ago this week but on film he lives on as Paul Naschy, the last of the old-school horror men, an interpreter of the classic monsters who translated the naive fantasies of Universal Studios into the idiom of Seventies exploitation without losing the original sense of wonder. To mark the anniversary of his passing I'm contributing to a memorial celebration blogathon coordinated by the Vicar of VHS and the Duke of DVD of Mad Mad Mad Mad Movies fame, but I fear that my tribute isn't all it could be. That's because I chose to watch Leon Klimovsky's Dr. Jekyll y el Hombre Lobo in a version provided by Mill Creek Entertainment as part of its new Pure Terror collection. In its original form, the film is 96 minutes long. Mill Creek's version is barely 72 minutes; more than a quarter of its running time is gone, including the opening credits. The remainder is an awkwardly disproportionate film that feels like two separate projects grafted together and leaves you wondering for the longest time when Dr. Jekyll might show up.We seem to be moving far from Jekyll territory immediately as Imre, an Anglo-Hungarian gentleman, and his new bride Justine take their honeymoon in the old country so Imre can commune with his dead ancestors. A well-off tourist, Imre is an instant target for the local riffraff, and he will go exploring in odd places despite warnings of a monster in a nearby castle. Why worry about monsters, though, when the countryside has plenty of mundane carjackers and rapists to offer? In short order Imre is stabbed to death and Justine is prepped for gang rape. All the while, however, a monster has been watching, but now Waldemar Daninsky has seen enough.

Before you can wonder how long our old friend has been watching -- did he miss the stabbing, or did he suppose the rapists might stop at some point of no harm done? -- the man in the black turtleneck strides into action. With Waldemar around, who needs a werewolf? The man himself can snap ribs with a bear hug and finish his victim with a rock to the face. He doesn't get them all, however, and that means vendetta! Daninsky's faithful leper lackey and his motherly witch of a keeper fall victim to a rapist's vengeance before Waldemar finally chokes the villain out. The werewolf gets his licks in, too.Waldemar Daninsky (Paul Naschy, below) works himself up to the proper state of outrage before intervening to break up a gang rape.

With his friends dead and a widow wanting to go home to England, there's nothing to keep Waldemar in Transylvania anymore. Indeed, Justine just happens to have a friend who might be able to help the poor Pole with that curse thing. The friend is Dr. Henry Jekyll, grandson of the famous fictional physician and inheritor of his research into the isolation and concentration of evil in human form. He's been busy refining granddad's formula, and he has an idea that could help Daninsky. It goes like this: Jekyll will inject Waldemar with granddad's formula just before the next full moon. Daninsky's transformation into Mr. Hyde will counteract the effect of the curse, Hyde's concentrated evil will being stronger than the werewolf's. Once the crisis is past, Jekyll will hit Hyde with the newly improved antidote, restoring a civil Daninsky and curing the curse. Despite a setback when Waldemar is trapped in an elevator at the rise of a full moon, slaughters a nurse, and rages into the night, everyone resolves to carry on with the experiment.

It may be an oddity of the dubbing, but you almost get the impression that "Mr. Hyde" is a default villain that anyone who takes the formula will turn into. Jekyll and his assistant Sandra (an homage to the femme fatale/mad scientist/vampire's assistant of Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein?) react to their successful transformation of Waldemar into a leering creep with Serverus Snape hair as if they had revived the "historic" Mr. Hyde. And as we'll see, "Hyde" has a decidedly retro fashion sense, when he isn't sporting an unflattering sweatshirt."Why do things happen?" Waldemar waxes philosophic just before tearing a nurse's throat out with his teeth. Below, the werewolf steps out.

Believe it or not, the experiment works. Jekyll's lab has the best restraints in the business. They hold down the werewolf in an early test, and they hold down Hyde while he whines about his blood boiling and his need to be free. The antidote does its work and Daninsky is himself again. That can't last. Turns out Sandra, also Jekyll's mistress, is jealous of Justine's attention to him. So at the moment of his redeeming triumph, Sandra stabs him in the back and injects the helpless, terrified Waldemar with another dose of Hyde serum. A madder scientist than her mentor, she apparently wants to see Hyde at his full power.Above, "Waldemar's Hyde!" The scientists mean to say that Waldemar is now Mr. Hyde, but he does show plenty of hide in this shot. Below, I saw Waldemar Daninsky in the streets of London, but the hair he wore was funny, through no fault of his own.

And here we come up against the limitations of the Mill Creek edition of the movie. In that, the reign of terror of Hyde Redux consists of 1) pushing a drunk into the Thames, 2)impaling Sandra on a torture device in a fit of temper and 3)flirting with girls in a bargain-basement discotheque in the dregs of Swinging London. It's a short reign; the Hyde formula is in limited supply, and in time an embarrassed Waldemar finds himself among the go-go dancers just as the full moon cues a nifty stroboscopic transformation scene. That sets up the inevitable showdown as the werewolf targets Justine, who may have learned to love Waldemar enough to kill him....

The Mill Creek version of Dr. Jekyll and the Werewolf is a colorful, picturesque and entertaining ruin. As usual, there's little in the way of continuity with past or future Daninsky movies. Waldemar is a cartoon character who can be rebooted after every fatal outing. His conduct is inconsistent from film to film. In Werewolf Shadow (aka The Werewolf vs. the Vampire Woman) Daninsky is conscientious about chaining and confining himself during full moon nights. Here, in the first half of the film, he strolls out as if it doesn't matter if he kills or not. Waldemar never quite has the overbearing guilty conscience of his precursor, Universal's Larry Talbot. Sure, he'd like to be cured, but it doesn't really seem to bug him (or his friends, for that matter) as much as it should that he's a mass murderer. If Talbot had had an elevator accident like Waldemar's, you know he'd be demanding to be locked up, or killed, the next morning. Here, Waldemar, Jekyll, Justine and Sandra just seem to shrug the episode off. It seems almost amoral but it may simply be a refusal of self-pity, Naschy the actor distinguishing himself from Lon Chaney Jr. by adopting an air of stoicism rather than despairing self-pity or self-righteous.Above, a Polish werewolf in London. Below, a continuity error: this shot of Shirley Corrigan as Justine comes from much earlier in the picture, but I thought it looked best here.

I'm reluctant to judge Klimovsky's film on such limited evidence, but I do feel that it retains the odd charm of Naschy's work. My only real complaint is the absence of a worthy antagonist for the werewolf to fight, it being impossible, after all, for Hyde and the Werewolf to fight. A good dream sequence could have taken care of that, however. Anyway, count me among those already won over by Paul Naschy's curious charisma and his commitment to the monster movie tradition. Even in its vivisected form, Dr. Jekyll and the Werewolf didn't damage my regard for the man and his work.

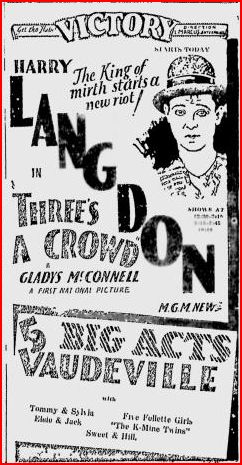

There's more where this came from all over the Internet this week. Look for this sign for a wide variety of Naschiana from fans and critics throughout the blogosphere.