With the debut of

Arrow in 2012, DC Comics stole a march on Marvel Comics in the kingdom of TV. DC held its ground in 2013 when Marvel launched

Agents of SHIELD, a show handicapped in its first months by storylines dependent on a movie not yet released and a dull cast, while

Arrow topped itself on the strength of Slade Wilson's mirakuru-enhanced villainy. While Marvel surprisingly stumbled out of the gate, DC expanded rapidly in 2014, with mixed results.

Gotham only seemed to get worse as the season wore on, but remained a ratings success, while

Constantine, better than just about anyone expected, withered on the vine of Friday night. Most importantly, Greg Berlanti, the creator of

Arrow, expanded his domain in every sense with

The Flash, a success with both the crucial target demographics and many TV critics. Berlanti has his own universe within DC's multimedia universe; it will expand in the coming season, definitely with

Legends of Tomorrow, on CW along with his other shows, and possibly with

Supergirl on CBS. For Berlanti,

Flash was a crucial evolutionary step from the relatively grim grit of

Arrow -- now imitated with greater self-importance to greater acclaim by Marvel on Netflix -- to a full-scale comic-book superhero universe. While Marvel TV has seemed minor-league in its initial focus on spies, though

SHIELD has been world-building aggressively more recently, with

Flash DC has introduced all the potential of superpowers to the small screen while nearly perfecting the CW formula of heroism complicated by relationships, which is basically the Marvel Comics formula of "super heroes with problems" from fifty years ago.

As

Flash acknowledges in its stunt-casting of John Wesley Shipp as its hero's father, the current show is TV's second try at DC's Scarlet Speedster. Shipp played Barry Allen in 1990's one-season series, a disappointment following the phenomenal success of Tim Burton's Batman movie the year before. The new show has honored the old show in other ways, from recasting Mark Hamill as a new version of his Trickster villain to the nearly mind-boggling casting of Amanda Pays as virtually the same character, down to the name, from1990. The modern Flash emulates the old show by giving Barry Allen a motivating personal issue that comic-book Barry Allen didn't need back in 1956. The founding character of the "Silver Age" of superhero comics, Barry Allen was a model of disinterested benevolence of the sort that modern readers and viewers are bored by or distrust. In more recent comics, Allen's origin was retconned to motivate him with a murdered mother, and so it is here. We first saw the new Barry Allen (Grant Gustin) on two second-season episodes of

Arrow, in which the young Central City police scientist came to Oliver Queen's Starling City to investigate possible "metahuman" activity. This was an obsession of Barry's because he remembered something, or someone, superhuman involved in the crime for which his father was convicted. Nothing came of the lead, though Barry flirted a little with Felicity Smoak and designed an adhesive mask for Ollie before returning home to be fried in his lab by the explosion of STAR Labs' particle accelerator. His own show began with Barry waking from a months-long coma, reuniting with his surrogate family, discovering his speed, and making new scientist friends. A rump operation at STAR is being conducted by Dr. Harrison Wells (Tom Cavanaugh), assisted by young prodigies Cisco Ramon (Carlos Valdes) and Caitlyn Snow (Danielle Panabaker). These last two aroused instant interest among comics fans because their names suggested that they were destined to become superheroes or villains themselves, while Wells was initially more mysterious. On the personal front, Barry returned home to police detective Joe West (Jesse L. Martin) and his daughter Iris (Candice Patton), on whom Barry has an understandable longterm crush, but who has hooked up during his coma with Joe's protege Eddie Thawne (Rick Cosnett). Eddie's last name also rang bells with comics readers. It marked him as an ancestor of Eobard Thawne, the "Reverse Flash" of the future and an arch-enemy of Barry Allen, if not the man himself.

The particle-accelerator explosion affected others besides Barry, giving them powers that mostly were used for evil. The STAR staff helped Barry fight these new menaces while learning to use his speed to maximum effect. At an early point Joe West learned Barry's secret and began collaborating with the STAR team, notwithstanding their extra-legal confinement of super-powered villains in containment cells at the facility, but in classic CW fashion he ordered Barry not to tell Iris, an aspiring journalist already interested in the "streak," about his powers and activities. In time Eddie Thawne, sometimes resentful of Barry as an enduring rival for Iris, was let in on the secret and became a reliable collaborator, if also a more reluctant keeper of the great secret from Iris. The CW lives on these secrets and their consequences, but

Flash handled this storyline with more understated credibility than

Arrow, where this season everyone had to keep Detective Quentin Lance from learning that his daughter Sara had been murdered, out of fear that the shock would stop his weak heart. While that seemed like archaic melodrama,

Flash's dilemma seemed more plausible and its resolution was taken care of quickly with a relative minimum of

sturm und drang. The show got enough of that elsewhere.

From episode to episode,

Flash's model was

Smallville, where Kryptonian radiation created a generation of "meteor freaks" for young Clark Kent to deal with. Strangely, it was on

Arrow where we first encountered an authentic metahuman whose origin could not be traced to the Central City particle accelerator incident -- a necessary event if Berlanti's universe is to be worth exploring beyond its two principal cities. Some of

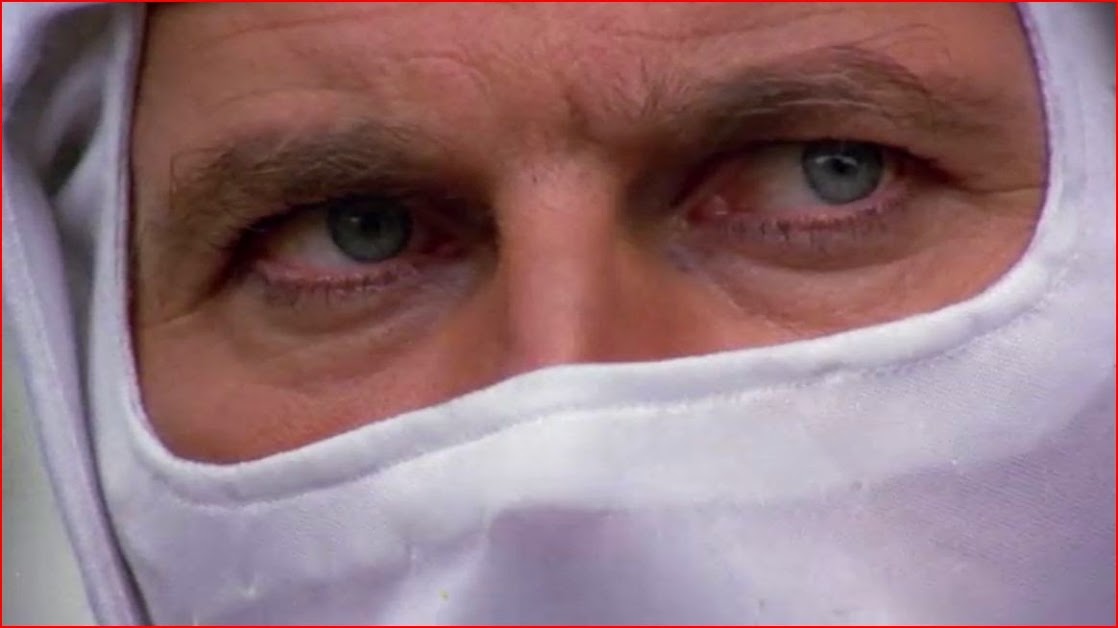

Flash's own antagonists weren't dependent on the explosion, from the old incarcerated Trickster and his modern imitator to the malevolent tech whiz Leonard "Captain Cold" Snart (Wentworth Miller) and his firebug sidekick "Heat Wave" (Dominic Purcell). The names usually aren't the villains' own ideas; genre geek Cisco gets to dub them in a weekly ritual. In comics, Flash has a rogues' gallery to rival Batman's or Spider-Man's, and after one season the show still has plenty to try out. They are a fantastic lot, from a man who can turn himself into a poison mist to the gorilla Grodd, experimented upon to develop near-human intelligence and super-human telepathy. All finally were overshadowed by the slowly revealed villainy of Harrison Wells, who became the show's most intriguing character. We knew something was up with him early on when he went into a secret chamber and consulted a hologram that appeared to be a newspaper from the year 2024, reporting the disappearance of the famous hero The Flash during some mysterious crisis (a Pavlovian trigger word for DC fans). Wells checked the paper frequently, apparently to confirm that history was still on a track that led to this crisis and disappearance, while mentoring Barry. Was it his job to train Barry for a necessary role in that crisis? Or was he the Reverse Flash from the future -- but if so, why encourage and help Barry? Since CW is taking the now-unusual step of repeating the entire season this summer, I won't spoil every detail, but Tom Cavanagh deserves a ton of credit here and now for crafting one of the best, most subtle supervillains in live-action media. Suffice it to say that he is a man from the future who has to stay in his past, our present, for a long time to carry out a longterm agenda that is ultimately selfish and ruthless. Yet he cannot live his life among us on this day to day, year by year basis without living largely according to the needs of the day. The remarkable thing about Wells is how he can engage, objectively if not disinterestedly, in each episode's problem-solving, even occasionally sacrificing his own agenda for the greater good of the moment. Whether he wanted to or not, he can't help but be a man of the present, and arguably to a great extent a good man, even as he furthers a longterm evil agenda. The show's writers deserve much of the credit for conceiving this character, but Cavanagh really sells it with a great poker face and an overall smooth demeanor befitting a man who's always working on several levels of strategy at once.

Cavanagh may have been Best in Show this season, but

Flash has been blessed with a strong ensemble cast, all of whom succeeded in deepening and enriching their characters over the course of the year. Grant Gustin is younger than the classic Barry Allen and sometimes seems more like a Peter Parker type, but he handles the material with easy conviction and does probably the best job possible within the modern "I'm learning this as I go along" paradigm. Carlos Valdes brightens the show with comedy relief that doesn't require him to be an idiot, since in fact he's a genius inventor with a possible metahuman destiny of his own, darkened by a vision of his own death that actually happened, only to be relegated to an alternate timeline. Jesse L. Martin's Joe West puts all the cops on

Gotham to shame, and that's before he really gets good as Barry's primary father figure and Iris's overprotective parent. As Iris, Candace Patton could have been a hated character as the show's mundane focus for shipping, but the character developed agency of her own as a reporter and now that she (like just about everyone else!) knows Barry's secret she'll be more team player than token romantic interest next season. As the third figure in the standard CW triangle, Rick Cosnett really took off in the later episodes once Eddie became a trusted part of Team Flash and had to deal with what was supposed to be his destiny, unless he had something to say about it. Some of the weekly villains were weaker than others, but there really was no weak link in the main cast. Add to the mix nearly unprecedented special effects for television and

Flash has just about realized what comics fans had hoped for over generations: a superhero show with an authentic comic book feel within a rapidly expanding comic book universe in all its dimensions of potential. The one real risk it faces moving forward is that Berlanti's creative team may overstretch itself as more shows go into production. The overall weakness of

Arrow's third season may be a warning sign, but to have produced

Arrow in the first place and now

Flash after the debacle of the

Green Lantern movie proves that Greg Berlanti learns from his mistakes. In any event,

Flash is the kind of show that inspires optimism, in bright contrast to the gloomy perspective of other shows, so I leave behind season one confident if not impatient for season two.

E

E