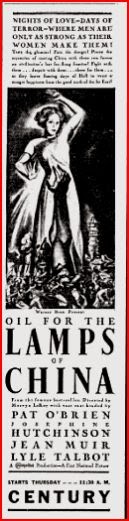

Of course, real love will bloom on Chinese soil while Chase struggles to make a success of himself. The complications are predictably melodramatic. In an extreme case, the now-genuine Mrs. Chase goes into dangerous labor just as Stephen is called away to deal with an oil fire. When he gets back home, he learns that their baby died. "I needed you" the doctor tells him -- for what is left unclear -- and he wife blames Stephen for putting his career before his family. She forgives him, but Atlantis is less forgiving of the unauthorized expenses involved in fighting that fire and avoiding a bigger disaster. Stephen perseveres and gets transferred to a big city where his knowledge of China proves advantageous. He emerges as the archetypal China hand, one of those rare Americans who "know" China and can deal with Chinese people. I had the impression that Atlantis trained all its people to know China, but apparently that training only sinks in to a few of them. It really boils down to mastering that formal politeness that so fascinated Americans while defining Chinese (and Japanese) people as alien. In short, Stephen knows how to butter up the traditional merchants with flattery and formality in order to keep them doing business with Atlantis -- until the revolution comes. Amid a Communist uprising, Keye Luke comes barreling into the picture as a military officer determined to confiscate Atlantis's gold holdings. Luke's fluency and natural manner of speaking made him a nearly unique figure in 1930s Hollywood. He became best known for playing Charlie Chan's buffoon of a son -- the Chinaman domesticated into a hapless American -- but in Oil his modernity conveys brusque menace as he brushes aside O'Brien's attempts at customary formality. Neither he nor China have time for that anymore, and his men drive the message home by shooting down Chase's Chinese merchant friend at the Atlantis doorstep. Despite Luke's threats, Chase manages to escape with the company's money -- and is rewarded with a demotion to a humiliating clerk's job at the head office. He knows he isn't being treated right, but he refuses to quit because doing so would cost him his pension. How much of a sap he's been all along is finally driven home when his wife confronts the boss to remind him that, after all this time, Stephen still holds the patent on that economy kerosene lamp. His condition improves rapidly from there, but the film closes with him embracing the wife and naively crediting the company with living up to its promises to him, while the wife does all but wink at the camera.

Warners did O'Brien no favor by casting him as Stephen Chase. Sure, it was a high-profile part based on a best-seller, but Chase hardly cuts a heroic figure here. It doesn't help that the studio apparently couldn't afford to show him fighting that oil fire. His battle to save a village is treated the way his wife sees it, as an unworthy distraction from the birth of his baby. A viewer might side with him awhile after everyone guilt-trips him, but it's hard to keep liking him when he never, ever wises up. He may be some sort of China expert -- though the film suggests that his expertise is growing obsolete -- but his real problem is that he can't understand the corporate culture in which he's embedded. At least he doesn't understand it as novelist Hobart (who based her writing partially on life experience) and adapter Laird Doyle see it. While O'Brien flounders, LeRoy does everything possible to tell the audience that the Oil movie is telling a lot less than the novel does. Perhaps the worst possible thing you could do while filming a literary adaptation is to use shots of flipping pages of the actual book as a transition device. Nothing you could do would say more clearly, "There's a lot of story here that we're just going to skip." Just about all literary adaptations skip a lot of story, or at least a lot of detail, but few are as guileless about admitting it as this one. It's not an endearing quality. Personally, I was hoping for something more pulpy, more self-consciously exotic -- something that hinted at what America was really thinking when it thought about China. Instead, Oil For the Lamps of China is a domesticated if not domestic melodrama that reduces the exploitation of an ancient empire to the dull ordeal of an organization man. For all I know it was faithful to the novel, but as a movie it's a big disappointment.

Warners did O'Brien no favor by casting him as Stephen Chase. Sure, it was a high-profile part based on a best-seller, but Chase hardly cuts a heroic figure here. It doesn't help that the studio apparently couldn't afford to show him fighting that oil fire. His battle to save a village is treated the way his wife sees it, as an unworthy distraction from the birth of his baby. A viewer might side with him awhile after everyone guilt-trips him, but it's hard to keep liking him when he never, ever wises up. He may be some sort of China expert -- though the film suggests that his expertise is growing obsolete -- but his real problem is that he can't understand the corporate culture in which he's embedded. At least he doesn't understand it as novelist Hobart (who based her writing partially on life experience) and adapter Laird Doyle see it. While O'Brien flounders, LeRoy does everything possible to tell the audience that the Oil movie is telling a lot less than the novel does. Perhaps the worst possible thing you could do while filming a literary adaptation is to use shots of flipping pages of the actual book as a transition device. Nothing you could do would say more clearly, "There's a lot of story here that we're just going to skip." Just about all literary adaptations skip a lot of story, or at least a lot of detail, but few are as guileless about admitting it as this one. It's not an endearing quality. Personally, I was hoping for something more pulpy, more self-consciously exotic -- something that hinted at what America was really thinking when it thought about China. Instead, Oil For the Lamps of China is a domesticated if not domestic melodrama that reduces the exploitation of an ancient empire to the dull ordeal of an organization man. For all I know it was faithful to the novel, but as a movie it's a big disappointment.

No comments:

Post a Comment